as a PDF

advertisement

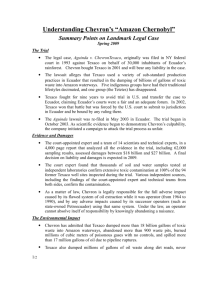

The Costs of Conflict Resolution and Financial Distress: Evidence from the Texaco-Pennzoil Litigation David M. Cutler; Lawrence H. Summers The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 19, No. 2. (Summer, 1988), pp. 157-172. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0741-6261%28198822%2919%3A2%3C157%3ATCOCRA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-8 The RAND Journal of Economics is currently published by The RAND Corporation. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/rand.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to and preserving a digital archive of scholarly journals. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. http://www.jstor.org Mon Apr 2 13:23:35 2007 RAND Journal of Economics Vol. 19, No. 2, Summer 1988 The costs of conflict resolution and financial distress: evidence from the Texaco-Pennzoil litigation David M. Cutler* and Lawrence H. Summers** This article demonstrates that the dispute between Texaco and Pennzoil over the Getty Oil takeover reduced the combined wealth of the claimants on the two companies by over $3 billion. During the course of the litigation, Pennzoil's shareholders gained only one-sixth as much as Texaco's shareholders lost. When the litigation was settled, about two-thirds of the loss in wealth was regained. These fluctuations in value exceed most estimates of the direct costs of carrying on the litigation, and may reflect the disruption in the operations of Texaco caused by the dispute. 1. Introduction From 1984 to 1988 Texaco and Pennzoil were engaged in a legal battle over Texaco's usurpation of Pennzoil in the takeover of the Getty Oil Company. The stakes were huge: the original jury award called for a payment of more than $10 billion; the companies ultimately settled for $3 billion. The Texaco-Pennzoil case presents a unique experiment for studying debt burdens and bargaining costs. Market assessments of the prospects of both parties in a prolonged dispute are rarely as observable as they are in the Texaco-Pennzoil case. Further, unlike in most other litigation settings and in almost all bankruptcy cases, the burden imposed on Texaco did not have a collateral effect on furture cash flows. This article examines the abnormal returns earned by the shareholders of Texaco and Pennzoil over the course of the dispute.' A clear pattern emerges. Events affecting the size * Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ** Haward University and National Bureau of Economic Research. We are grateful to Gordon Cutler, Lany Katz, Greg Mankiw, Jim Poterba, Myron Scholes, Andrei Shleifer, Vicki Summers, A1 Warren, and two anonymous referees for comments on an earlier draft. Becky Boman, Steve Coll, Alan Edgar, Andrew Grey, Gary Hindes, Allanna Sullivan, Tom Petzinger, and Dan Wilhelm provided valuable information on different aspects of the case. This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Sloan Foundation. A data appendix has been deposited at the University of Michigan archive. After circulating an early draft of this article, we became aware of work by Engelmann and Cornell (1988) on the wealth effects of several large corporate disputes, including the Texaco-Pennzoil case. They note the asymmetric returns as well, but concentrate on events at the beginning of the case. Bhagat, Brickley, and Coles (1987) examine stock price movements to news in a large number of corporate legal cases and obtain similar results. Mnookin (1987) discusses the reasons Texaco and Pennzoil failed to settle the litigation earlier. Baldwin and Mason (1983) in related work examine the market reaction to the Massey Ferguson bankruptcy case and find that the resolution of the bankruptcy resulted in a substantial increase in the value of the company. ' 158 / THE RAND JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS of the transfer resulted in opposite but asymmetric returns to the two companies: when its obligation to Pennzoil was increased, Texaco's value fell by far more than Pennzoil's rose; the opposite reaction occurred for events reducing the expected transfer. These "leakages" in value were enormous: each dollar of value lost by Texaco's shareholders was matched by only about 40 cents' gain to the owners of Pennzoil. The ongoing dispute reduced the combined equity value of the two companies by $3.4 billion, over 30% of the joint value of the two companies before the dispute arose. A large fraction of the losses in combined value was restored when the case was settled. The precise impact of the settlement is difficult to gauge, however, because of the coincidence between the case's settlement and takeover threats to Texaco. After documenting these large fluctuations in joint value, we seek to identify their causes. One explanation is the fees that both companies paid to the many lawyers, investment bankers, and advisors that were retained. These costs seem too small to account for the large swings in joint value, however. A second explanation is that a settlement would have been wasted by Pennzoil and thus was discounted by the market. This explanation seems inconsistent with the large increase in value after the resolution of the dispute, however. It appears either that there were additional costs to Texaco's shareholders that were relieved by the settlement, or that the claims on the two companies were valued inefficiently during the litigation. We conclude by discussing a number of implications for economic analysis. First, the large losses illustrate that efficient bargains will not always be struck, even when neither side possesses much relevant private information. Second, the losses suggest that financial conflict can have substantial effects on productivity. This has implications for bankruptcycost explanations of firms' debt-equity choices, macroeconomic theories that stress credit disruptions as an important element in business-cycle fluctuations, and arguments that debt relief for major debtor nations would make all parties to the LDC debt crisis better off. The article is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly recounts the history of the dispute and describes the event-study methodology we use. Sections 3 and 4 document the large changes in joint value during the litigation. We focus first on the equity claimants, and then on other claimants-bondholders and the Federal government. Section 5 examines potential causes of the fluctuations in joint value. Section 6 concludes with some implications of our findings. 2. The Texaco-Pennzoil conflict The Texaco-Pennzoil dispute arose from the bids both companies made to acquire Getty On January 2, 1984, Pennzoil reached what it felt was a binding agreement with the directors of Getty Oil to acquire 3/7 of Getty. Within a week of the Pennzoil-Getty proposed sale, however, Texaco purchased all of the Getty stock at a higher price per share. As a condition of the sale, Texaco indemnified Getty and its largest shareholders against any possible litigation. Thus, when Pennzoil sued for breach of contract, Texaco became liable for damages. The case was ultimately brought before the Texas State Court and was tried in mid1985. A decision was reached on November 19, 1985 (event 1) in favor of Pennzoil, with the judgment for $7.53 billion in actual damages, $3.0 billion in punitive damages, and $1.5 billion in accrued interest. The jury's decision was widely decried in the press. Commentators uniformly attacked the size of the judgment because it was based on the replacement cost of the oil that Pennzoil would have obtained from Getty, not on the damages The description of the dispute here is necessarily brief. Entertaining narrative histories of the Getty case may be found in Petzinger (1987) and Coll (1987). We have also drawn heavily on the ongoing reporting of the Wall Street Journal and New York Times. CUTLER AND SUMMERS / 159 that Pennzoil suffered by failing to acquire Getty at the agreed-on price. There was a widespread expectation that the judge would either overturn the judgment or reduce the damages substantially. Notwithstanding these predictions, on December 10, 1985 (event 2), the Texas judge denied Texaco's request to overrule the jury, and affirmed its award. Under Texas law Texaco was required to post a bond in the full amount of the judgment to appeal the case. Texaco objected to the requirement and appealed the issue to the Federal Court in New York. On December 18, 1985 (event 3), Texaco received a Temporary Restraining Order prohibiting Pennzoil from attaching liens to Texaco's assets until the bond matter could be decided. A hearing on the requirement was held in early January 1986, and on January 10, 1986 (event 4), the Federal judge ruled that Texaco had to post only a $1 billion bond to appeal the case. A Federal Court of Appeals upheld this ruling on February 20, 1986 (event 5). After the Appeals Court ruling, both companies appealed the decisions favorable to the other side. Texaco obtained a hearing on the original case in the Texas Court of Appeals, and on February 12, 1987 (event 6) that Court upheld all but $2 billion of the judgment for Pennzoil. On April 6, 1987 (event 7), the Supreme Court vacated the Federal Court ruling. Faced with liens being placed on its assets, on April 12, 1987 (event 8), Texaco filed for bankruptcy. Although Texaco was in bankruptcy, it continued its appeal of the case. In June an appeal was filed with the Texas State Supreme Court. Pennzoil, meanwhile, appealed the bond reduction to the United States Supreme Court. On November 2, 1987 (event 9), the Texas State Supreme Court declined to review the case and left standing the Appeals Court judgment. After the Texas Supreme Court decision, Texaco and Pennzoil held a final round of settlement negotiations. From November 19to December 10, 1987,the companies negotiated a "base-cap" settlement, which would have limited overall liability ("the cap") in exchange for a nonrefundable "base" payment. Despite Texaco's announcement to the Bankruptcy Court that the companies had made great progress (December 2, 1987), they were unable to reach an agreement. Independently, on December 11, 1987, Texaco's shareholders' committee, in conjunction with Carl Icahn, reached a $3 billion settlement with Pennzoil. On December 18 the two companies formally agreed to this amount. 3. The effects of the conflict on shareholder wealth Methodology. To measure the impact of the conflict on the two companies, we examine the abnormal changes in equity values induced by news bearing on the litigation. We use the market model to measure abnormal return^:^ + + Rit = a, P,R,, €it, (1) where R,, and R,, are the return to stock i and the market at time t. The abnormal return is measured as the residual, ei,. We multiply the abnormal returns by the value of the outstanding equity of each company to estimate the changes in wealth caused by the litigati~n.~ Market response. As a first test of the impact of the dispute on equity values, we examine the correlation between the stocks' abnormal returns. If litigation news was frequent and had large effects, the two returns should show a lower correlation than would otherwise Fama, Fisher, Jensen, and Roll (1969) and Schwert (1981) discuss the methodology more fully. We use return data from January 1984 to January 1988. The data were adjusted for dividend payments and stock splits. We used the return on the Standard and Poor's Composite Stock Index as a proxy for the market return. The results are invariant to the time period used for the estimation. 160 / THE RAND JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS be expected. This appears to be the case. For seven oil companies not involved in the litigation,' the average painvise correlation of abnormal returns is .249, with a standard deviation of .17 1. For Texaco and Pennzoil, the correlation is .0 16.'j Thus, the litigation appears to account for a large fraction of the return variance of both c ~ m p a n i e s . ~ The most natural measure of total litigation costs is the change in value of the two companies in reaction to important events. Tables 1 and 2 show the effects of each of the events described in Section 2 on the market value of the two companies and on the combined equity values8 Table 1, which focuses on the effects of litigation news, provides strong evidence that the market associated large costs with the Texaco-Pennzoil dispute. While Texaco's and Pennzoil's share prices almost always moved in opposite directions, Texaco's change in value was much larger than Pennzoil's. In the six events decided against Texaco (events 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, and 9), Texaco's one-day loss was 5.1 times greater than Pennzoil's gain. In only one case did Pennzoil gain even half as much as Texaco lost. While the results are weaker for the decisions favoring Texaco (events 3, 4, and 5), they nonetheless support the view that the costs of the conflict are large. With the exception of the Federal Court bond reseems to benefit greatly; the return to Pennzoil is less clear. Both the d u ~ t i o n Texaco ,~ individual changes in value and the change in combined value are statistically significant at conventional levels. The combined loss to shareholders from these nine events is striking. Using single-day returns, we find that Texaco's value fell a total of $4.1 billion; Pennzoil's rose only $682 million. Pennzoil gained only 17% of what Texaco lost. Before the litigation was filed, Texaco's value was about $8.5 billion, while Pennzoil's was about $2 billion. The loss thus represents over 32% of the prelitigation joint value. Table 1 also shows that the two stock prices moved together after the bankruptcy filing of Texaco. On the day after the filing, joint value fell by over $1.2 billion. It was widely reported that the losses were caused by disappointment on the part of shareholders over the failure to settle the case the week before.'' The implication is that events that were expected to prolong the dispute or to magnify what was at stake led to large losses in joint value. In contrast to the news about the magnitude or duration of the litigation, Table 2 shows that the events associated with the resolution of the dispute resulted in large increases in combined value. Using single-day returns, we find that joint value increased by $2.3 billion after the four settlement announcements in November and December 1987. This rise in value is 65% of the loss from the litigation events, although the prolonged negotiations make it more difficult to identify all days on which expectations of a settlement changed. These companies were Ashland Oil, Arco, Chevron, Exxon, Mobil, Occidental, and Unocal. The data were from January 1985 to December 1987. One possible explanation for the small correlation is that periods of nontrading result in noncontemporaneous reactions to the same news. If this were true, the one-period lead or lag returns should be positively correlated. Leading and lagging Texaco's return by one period, however, yields correlations of -. 107 and .03 1. We thus reject this explanation. This test actually understates the significance of the dispute because some events, such as the bankruptcy filing by Texaco and the settlement talks the two companies held, caused the two stock prices to move together. The standard errors for the change in combined value were computed from a portfolio containing a weighted average of Texaco and Pennzoil shares, where the weights were the market value of the companies at the end of the previous day. Appendix Table A1 repeats the analysis by using the return on the Standard and Poor's Composite Oil Index as a proxy for the market return. The results are similar to those in Table 1. The New York Times commented that the returns on this day were partly a reaction to the court ruling and partly a reaction to a fall in oil prices. As Table A1 shows, Texaco lost much less value in relation to the Oil Index in this week. ' O The New York Times, for example, speculated that the inability of Texaco and Pennzoil to settle before the bankruptcy filing probably added four years to the projected length of the dispute. CUTLER AND SUMMERS / TABLE 1 161 Litigation News and Changes in Value* One Day after Announcement Change in Value ($ million) No. Event 1 November 19, 1985: Texas jury rules for Pennzoil 2 Pennzoil Combined Pennzoil Combined -$646.3 (164.3) $295.7 (44.8) -$350.6 (166.4) -$1,124.3 (336.7) $483.3 (1 15.7) -$731.0 (366.7) December 10, 1985: Texas state judge affirms jury award -$580.8 (128.7) $18.9 (60.1) -$561.9 (147.7) -$806.6 (273.9) -$137.5 (134.5) -$946.1 (3 18.8) 3 December 18, 1985: Texaco obtains Temporary Restraining Order $445.8 (1 15.6) -$126.6 (58.5) $3 19.2 (135.8) $686.2 (276.7) $77.9 (128.4) $764.1 (3 16.9) 4 January 10, 1986: Bond requirement reduced -$125.2 (13 1.9) -$88.3 (64.6) -$213.5 (153.4) -$407.1 (286.5) -$88.7 (143.1) -$495.8 (335.1) 5 February 20, 1986: Federal Court upholds bond reduction $6.7 (124.7) $23.7 (51.5) $30.4 (138.4) $161.7 (280.2) -$14.6 (1 17.0) $147.1 (3 11.9) 6 February 12, 1987: Court of Appeals upholds judgment -$8 18.7 (18 1.0) $378.6 (66.9) -$440.1 (195.5) -$1,092.0 (370.3) $200.6 (163.6) -$89 1.4 (4 18.0) 7 April 6, 1987: Supreme Court vacates bond rulings -$l,O00.l (176.9) $267.2 (80.0) -$732.9 (199.4) -$1,257.4 (360.5) $498.6 (183.5) -$758.8 (423.8) 8 April 12, 1987: Texaco files for bankruptcy -$697.5 (149.8) -$56 1.5 (87.6) -$1,259.0 (184.1) -$308.4 (302.6) -$645.9 (175.2) -$954.3 (382.2) 9 November 3, 1987: Texas Supreme Court denies appeal -$681.5 (161.0) $474.7 (52.8) -$206.8 (169.2) -$989.2 (329.9) $563.9 (143.1) -$425.3 (370.2) -$4,097.6 (453.6) $682.4 (192.8) -$3,415.2 (501.1) -$5,137.1 (945.0) $937.8 (439.9) -$4,199.5 (1,087.9) Total Litigation Events Texaco Five Days after Announcement Change in Value ($ million) Texaco * Table shows change in value of Texaco, Pennzoil, and combined equity. The change in combined value is computed from a value-weighted portfolio of Texaco and Pennzoil shares. Numbers in parentheses are the standard errors expressed as changes in value by multiplying by the market value of the firm or portfolio. Unfortunately, the magnitude of the gain is also obscured by the involvement of Carl Icahn in the settlement process. The threat of a takeover by Icahn potentially induced a premium in Texaco's value. While we discuss this aspect of the case more fully in a later section, we note here that on several days when the news was almost exclusively about the negotiated settlement-the days reported in Table 2-joint value rose substantially. Settlement announcements appeared to increase the value of both companies. Immediate responses to dispute events thus indicate that news that increased either the expected transfer from Texaco to Pennzoil or the expected duration of the dispute greatly reduced the combined value of the two companies. Not all information bearing on the 162 / THE RAND JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS TABLE 2 Settlement News and Changes in Value* One Day after Announcement Change in Value ($ million) No. Event Texaco 1 November 19, 1987: Pennzoil proposes base-cap settlement 2 December 2, 1987: Texaco reports progress in negotiations 3 December 11, 1987: Shareholders' Committee and Pennzoil agree to settlement 4 December 18, 1987: Texaco and Pennzoil agree to settlement Pennzoil Combined Five Days after Announcement Change in Value ($ million) Texaco Pennzoil Combined Total Settlement Events * Table shows change in value of Texaco, Pennzoil, and combined equity. The change in combined value is computed from a value-weightedportfolio of Texaco and Pennzoil shares. Numbers in parentheses are the standard errors expressed as changes in value by multiplying by the market value of the firm or portfolio. TABLE 3 Monthly Excess Returns* Change in Value ($ million) Month November 1985 December 1985 January 1986 February 1986 March 1986 April 1986 May 1986 June 1986 July 1986 August 1986 Texaco Pennzoil Combined CUTLER AND SUMMERS / 163 Continued TABLE 3 Change in Value ($ million) Month Texaco Pennzoil Combined September 1986 October 1986 November 1986 December 1986 January 1987 February 1987 March 1987 April 1987 May 1987 June 1987 July 1987 August 1987 September 1987 October 1987 November 1987 December 1987 January 1988 Totals November 1985-October 1987 November 1987-December 1987 * Table shows sum of abnormal returns for each week in the month. Abnormal returns are relative to the Standard and Poor's Composite Oil Index. Numbers in parentheses are standard errors expressed as changes in value by multiplying by the market value of the firm or portfolio. ultimate resolution of the case came out in discrete events, however. To assess the full effect of the dispute on the two companies, Figure 1 plots the cumulate changes in the abnormal returns of Texaco and Pennzoil over the course of the dispute. We present excess monthly returns for the two companies in Table 3. 164 / THE RAND JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS FIGURE 1 COMBINED V A L U E OF TEXACO A N D PENNZOIL It is apparent from Figure 1 that most of the movements in the combined value of the companies were associated with the major events highlighted in Tables 1 and 2. The total decline in value between the initial verdict in November 1985 and October 1987 was $3.7 billion, about the same as the sum of the losses in value during the case. Settlement of the dispute in November and December 1987 was associated with a gain of $2.6 billion in combined value. These totals suggest that the conflict between Texaco and Pennzoil cost their equity holders about $1 billion. 4. The effects on other claimants There are two principal claimants, in addition to Pennzoil, that stand to be affected by the litigation: the holders of Texaco debt and the Federal government, through its tax claim on the two companies." We examine the impact on these claimants in turn. W Texaco's bondholders. Litigation and bankruptcy pose two problems for bondholders. First, under the terms of the reorganization, their claims can be reduced or eliminated entirely. Second, in the event of liquidation, bondholderscan suffer (or gain)from redemption of the outstanding debt at par value, not market value. Exclusive of Pennzoil, Texaco's bondholders were its largest claimants throughout the litigation period.'' We therefore focus on the induced change in the value of Texaco's bonds. To determine these changes we used the following procedure. For each issue listed on the event day, we computed the abnormal return relative to a long-term oil company bond.I3 I ' The effect on Pennzoil's bondholders is not included since the value of these claims was never in doubt. The price of Pennzoil debt moved very little over the period and showed no exceptional movements in response to any of the litigation events. l 2 At the time of bankruptcy Texaco had $8.4 billion in bonds outstanding, of which $6.8 billion were long-term. "We used a 6% coupon rate, 1997 expiration Exxon bond. CUTLER AND SUMMERS / TABLE 4 Number 165 Change in Value of Texaco Debt* Date Average Excess Return Change in Market Value ($ million) Litigation Events November 19, 1985 December 10, 1985 December 18, 1985 January 10, 1986 February 20, 1986 February 12, 1987 April 6, 1987 April 12, 1987 November 3, 1987 Total Litigation Even Settlement Events 1 2 3 4 November 19, 1987 December 2, 1987 December 11, 1987 December 18, 1987 Total Settlement Events 8.1% $488.4 * Table shows change in value of Texaco debt. Average excess return is found as a weighted average of excess returns for individual issues. Change in market value is the book value of long-term debt at the end of the previous quarter times the average priceto-book value ratio, times the average excess return on the debt. Using book value weights, we then computed a weighted-average debt return. In addition, we computed a weighted-average price-to-book-value ratio on the day before the event. To find the change in debt value we multiplied the book value of long-term debt as of the end of the previous quarter by the price-to-book-value ratio (to find the market value of debt) and by the abnormal return on the debt. Table 4 shows the changes in debt value on each of the important events.14The return to bondholders mirrored that to stockholders. Adverse events in the litigation proceedings (events 1 , 2 , 6 , 7 , 8 and 9) reduced the value of the debt; favorable announcements generally increased the value. The aggregate effect of the nine litigation events is a fall of $1.5 billion in debt value. This figure obtains despite the fact that debt selling below face value fell by much less than higher yield debt. When Texaco filed for bankruptcy, for example, its average debt value fell by almost 12%,while the value of some of its low-yield debt fell by only 2%. As with the equity claims, settlement induced large increases in debt value. After the four settlement events, Texaco's debt increased in value by $488 million. Since takeovers should not affect debt payments, the magnitude of this increase suggests that the cause of the dramatic increase in value, for the bondholders and potentially for the stockholders, was primarily the resolution of the underlying dispute. The government. Under Federal law, damage payments are both taxable on receipt and deductible on payment. Thus, one might expect that the litigation would not affect government tax collections. Three considerations suggest that the litigation could have tax consequences, however. -- - - Because Texaco's bond prices are not carried on any financial databases, we were unable to calculate standard errors for the changes in bond value. l4 166 / THE RAND JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS First, it seems unlikely that Texaco could use all of the tax losses generated by a payment to Pennzoil. Between 1982 and 1986 Texaco received tax refunds four times; earnings and previous taxes were thus clearly inadequate to offset the losses immediately.'5 At year-end 1987 the company reported $4.9 billion in losses and write-offs. Second, the distinction in the tax law between ordinary income and capital gains could have lowered the tax liability of Pennzoil upon any receipt in 1986 or 1987. By purchasing assets from Texaco at a below-market price, Pennzoil could have avoided all but capital gains taxes on the step-up in basis of the assets. Since a settlement of this type was considered the most likely source of payment in that period, the implied tax liability may have been based on the capital gains rate.I6 Third, Federal law stipulates that in cases of "involuntary conversion" of property into similar property or cash used to purchase similar property within two years, the recipient of the resulting capital gain is not liable for tax on the gain." It is possible that Texaco's payments to Pennzoil would qualify as an involuntary conversion of Getty assets and so would be untaxed. Pennzoil has stated that it intends to file such a claim. It is not clear whether an involuntary conversion claim would be accepted by the IRS, however. The tax consequences of a settlement are thus uncertain, both for the liability upon receipt and for the deduction upon payment. A consideration of debt and taxes together, however, makes it clear that the claims of these creditors do not counter the large initial loss in value or the subsequent increase. Even if the market had anticipated that Texaco could not use any tax deductions, that the payment to Pennzoil would have been taxed at a 28% capital gains tax rate, and that the payment from Texaco to Pennzoil would have equalled Texaco's loss in value, not Pennzoil's gain in value, the tax liability in the presettlement stock prices would have come to only $950 million, which is less than the $1.5 billion loss suffered by Texaco's bondholders. l8 Further, the settlement substantially increased debt value, although the agreement on a cash transfer might have implied a higher overall tax payment.19 We thus conclude that the effects on nonequity claimants cannot explain the equity losses, and that the fluctuations in equity value did not reflect transfers among claimants. 5. Where did the value go? One explanation for the large swings in value is that the money would have been paid to the bankruptcy lawyers, trustees, and other litigation participants that both companies hired, and that these costs were saved by the settlement. Certainly, lawyers on both sides were numerous, and legal fees were large. It is difficult to believe that the market had expected future fees for the case to be as large as $2 billion, however. On August 27, 1987, Texaco announced that its legal fees since I S Texaco's financial statements do not report the amount of tax loss canyforwards the company has accumulated, but did indicate that Texaco had some loss carryforwards. l6 There was also some discussion about ways of structuring transfers to make them entirely tax free. Generally, these involved taking assets from both companies and putting them in a potentially tax-free third company, which would be jointly owned by the two groups of shareholders. Such transfers, however, were noted to be difficult to structure, and there was no guarantee that the transfer would be tax free. Much more journalistic attention was paid to schemes to "transform" receipts from ordinary income to capital gains. We thus focus on this more narrow tax consequence. l 7 An involuntary conversion is defined as: "(1) destruction of property in whole or in part; or (2) theft; or (3) actual seizure; or (4) requisition or condemnation or threat or imminence of requisition or condemnation." l 8 Indeed, even if the loss in value were the result of expected taxes or payments to the litigation participants, it is still a puzzle why the companies did not regain this value by negotiating an agreement sooner. l 9 If the market was expecting a 2890 rate before the settlement, a $3 billion payment taxed at the 34% rate would be an increase in expected tax payments of $180 million. CUTLER AND SUMMERS / 167 the original jury decision had been $55 million. Texaco also had to pay an estimated $3.5 million each month for the bankruptcy expenses of the company and of the creditor committees. Over a five-year period the present value of a continuation of these payments is about $250 million. Since legal fees are deductible from taxable income, the after-tax cost would have been only $165 million. It is unclear how much the market had expected Pennzoil to pay in total legal fees. Pennzoil's lead attorney, Joe Jamail, handled most cases on a contingency-fee basis. When asked about his fees, he was known to joke that the only math he knew was how to "divide by thirds" (Petzinger, p. 20). Jamail, however, insisted that he had no set fee for the case, and claimed that he took the case to help his friends at Pennzoil. Estimates of fees could thus have varied widely.20 Future market reactions, however, suggest that Pennzoil's expected legal fees were not large relative to the loss. After the settlement Pennzoil announced on December 29, 1987, that its costs for the case were $400 million, $200-$300 million of which was estimated to go to Jamail. The abnormal return for Pennzoil on that day was -$I1 3.4 million, which suggests an expected fee of at most $200 million. Thus, even if Pennzoil had additional future and past fees equal to Texaco's, the after-tax legal payment for both companies would be only $525 million, or 15% of the loss in joint value. Further, the reduction in fees from the settlement would explain only 14% of the resulting increase in value. A second explanation for the fluctuations in value is that Pennzoil would not use any funds it received from Texaco so efficiently as Texaco would. Such explanations are consistent with the findings of Jensen (1986) that free cash flow may be invested at below the market return, thus lowering the value of the company. We find it difficult to believe that this explanation can account for the large value fluctuations, however. Throughout the litigation the most commonly discussed settlement was a transfer of oil and gas properties. There would thus be no cash for Pennzoil to misuse. Further, Texaco has historically had among the highest finding costs in the oil industry, and has certainly been much less efficient than the settlement between the companies called for a payment in cash, not ~ e n n z o i l .Finally, ~' property. If the loss were due to potential wastefulness on the part of Pennzoil, the settlement should have been associated with a further reduction in joint value. A third explanation for the large loss is the secondary costs of the dispute on Texaco's profitability. By creating uncertainty about Texaco's long-term viability, making it difficult for Texaco to obtain credit, and distracting Texaco's management, the litigation may have reduced Texaco's value by more than the expected value of the transfers it would have to make to Pennzoil. Effects of this kind have been stressed in discussions of credit constraints (Greenwald and Stiglitz, 1987) and of the burdens associated with LDC debt obligations (Sachs and Huizinga, 1987). The most important evidence for the adverse effects of the dispute is an affidavit Texaco submitted with its bankruptcy filing that described the effect of the week-old Supreme Court decision on its operations. The affidavit asserted that some suppliers had demanded cash payments before performance or insisted on secured forms of repayment. Others halted 20 Most discussions of Jamail's fees indicated that Pennzoil and Jamail had yet to agree on a dollar amount, although it was certain to be less than Jamail's usual award. There was occasional speculation that his fees would be rather large. The Wall Street Journal reported that "[slome well placed Wall Street sources say they understood Mr. Jamail stands to collect 20% of the jury's award, which, if upheld, would result in a mind-boggling $2.4 billion for him" (November 21, 1985, sec. I, p. 2, col. 3). This was the only estimate this large, however, and the amount was never repeated. Given the future stock market reaction, it seems reasonable to conclude that this figure was an overestimate of market expectations. From 1983 to 1985 Texaco averaged $27.6 per barrel of oil and natural gas found, while Pennzoil averaged $16.3. The industry average for the 1984 to 1985 period was $10.9. 168 / THE RAND JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS crude shipments temporarily or cancelled them entirely. A number of banks had also refused to enter into, or placed restrictions on, Texaco's use of exchange-rate futures contracts. The affidavit concluded: The increasing deterioration of Texaco's credit and financial condition has made it more and more difficult, with each passing day, for Texaco to continue to finance and operate its business. . . . As normal supply sources become inaccessible and other financing is unavailable, Texaco's operations will begin to grind to a halt. In fact, Texaco is already having to consider the prospect of shutting down one of its largest domestic refineries because of its growing inability to acquire crude and feedstock. This sentiment was echoed by journalistic accounts of Texaco's actions. The New York Times, for example, noted that "Texaco has been under extreme financial pressure to resolve the case because of nervousness among its lenders, suppliers, and business partners about its future" (December 21, 1985, sec. I, p. 37, col. 5). Some analysts even attributed the stock market reaction to these costs. The Wall Street Journal reported: One analyst says he believes the market is assuming that Texaco will have to pay roughly $5 billion in cash to Pennzoil. But the market has discounted Texaco's stock even further because, he says, the company already has been damaged by the litigation. "They've been unable to refinance debt, they've missed opportunities in the oil patch, and the diversion of management has to cost something" (April 8, 1987, sec. I, p. 3, col. 5). Unfortunately, no direct evidence exists on whether these operational problems were really of major importance.22 Indeed, the day after the affidavit was filed, some of the suppliers mentioned specifically disputed Texaco's assertions. The principal evidence of their importance is the observation that most reasonable measures of conventional litigation costs are far below the observed fluctuations in joint value. A fourth explanation for the large fluctuations in value is that the market response reflected changing probabilities of a takeover of either Texaco or Pennzoil. If the market associated favorable litigation announcements with increased takeover probabilities and adverse litigation announcements with less likely probabilities, the resulting fluctuations in takeover premiums would mirror the observed changes in joint value. Changing takeover probabilities seem implausible as an explanation of the reduction in combined value during the litigation period. After the initial litigation decisions, it was widely commented that the losses increased, rather than decreased, the likelihood that Texaco would be taken over. The New York Times, for example, reported that "[tlhe damage to Texaco could spread far beyond the verdict. . . . The decline [in Texaco's stock price] was so dramatic that Texaco prepared a poison pill that would make a takeover prohibitively costly." It further noted that "analysts said the ruling could send Texaco's stock price down further and perhaps attract a hostile bid from a company hoping to buy Texaco at a bargain price" (December 11, 1985, sec. IV, p. 4, col. 4). It is much more likely, however, that a takeover premium was responsible for a large part of the increase in value at the conclusion of the dispute. The news media widely noted Carl Icahn's history of acquiring companies in hostile takeovers. Indeed, on the day that Icahn's first purchases of Texaco's shares were announced, the abnormal returns were $556 million for Texaco's equity and $182 million for ~ e n n z o i l ' s After . ~ ~ the settlement was announced the following month, the New York Times indicated that many takeover specialists saw Texaco as undervalued and were thinking about investing in it. It is unclear how much of the settlement revaluation should be attributed to takeover premiums, however. Although Icahn's initial purchases of Texaco's stock resulted in large 22 Attempts to analyze Texaco's financial statements for evidence on the effects of the litigation were complicated by the large gyrations in oil prices that occurred over the period. 23 It was mentioned in the press that Icahn had purchased about 2% of Pennzoil's shares in addition to his Texaco purchases, although analysts noted that the large amount of Pennzoil's stock held by the Chairman of the company made a takeover of Pennzoil unlikely. CUTLER AND SUMMERS / 169 increases in value, his subsequent actions had little effect on market values. When Icahn filed a notice with the SEC stating his intentions to increase his shares in the company, for example, Texaco's value rose by only $38.5 million. Two weeks later, when Icahn first threatened to file his own reorganization plan, Texaco's value fell by $18.5 million. These small revaluations suggest that, at least as of the time of the settlement, the involvement of Icahn in the dispute may have signalled only that a resolution of the dispute was forthcoming. A final explanation for the large fluctuations is that the market inefficiently valued the claims of the two companies, perhaps because many investors were unwilling to hold stock in a potentially or actually bankrupt company like Texaco, and other investors did not step in to fill the gap.24Consistent with this view, there is evidence that news provided by the companies resulted in asymmetric returns to the two stocks. On October 8,1987, for example, Pennzoil's value rose by $170.2 million and Texaco's fell by $42.0 million because "the company impressed industry analysts in New York with a presentation explaining its position in its protracted legal dispute with Texaco" (New York Times, October 9, 1987, sec. IV, p. 3, col. 1). The hypothesis of market error in valuing Texaco and Pennzoil is attractive, given our inability to locate large costs of the ongoing struggle. If Texaco and Pennzoil were valued inefficiently, however, there must be strong general grounds for doubting the rationality of market valuations. Unlike many important events, the principal uncertainty in the TexacoPennzoil case involved matters of public record. Further, both Texaco and Pennzoil were widely followed and actively traded throughout the period. Finally, the valuation pattern persisted over two years, and was noted on several occasions in the financial press. 6. Conclusions and implications Our results suggest that the Texaco-Pennzoil dispute reduced the combined wealth of the claimants on the two companies by about $2 billion. These costs seem much larger than reasonable estimates of the transfers the case was likely to generate. Given these large costs, it is natural to wonder why a bargain was not struck sooner. Theories of bargaining under complete information such as Rubinstein's (1982) work usually imply that if both parties are fully informed, bargains should be struck immediately and bargaining costs should not be incurred. Settlement did not take place in the Texaco-Pennzoil conflict, however, until four years after the dispute arose. The most commonly advanced explanations for failure to come to immediate agreement are differing expectations about the ultimate outcome, delaying settlement as a means of signalling private information, and committing to an inefficient outcome to influence the range of potential solutions (Crawford, 1982; Farber and Bazerman, 1987). These arguments seem like weak reeds in the Texaco-Pennzoil case. The principal uncertainties revolved around likely legal judgments that both parties had equivalent capacities to predict. Further, we have seen no indication that the parties had private information about their own financial condition. Finally, commitment does not seem credible when the case will be decided by a third party. Journalistic accounts typically explain why no bargain was struck by pointing to the mutual antipathy between the executives of the two companies. Two billion dollars, however, seem like a lot to pay to engage in pique. In the end it seems that something other than asymmetric expectations or information lay behind the inability of Texaco and Pennzoil to settle the case, or alternatively, that if the amount of asymmetry in this case is enough 24 The argument that the combined value of the two companies was depressed because of risk aversion founders on the observation that investors could purchase shares of both companies and thus profit from the settlement revaluation. 170 / THE RAND JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS to explain why almost $2 billion were nearly sacrificed in bargaining costs, that asymmetry must be present in almost every bargaining ~ituation.'~ The costs of Texaco's financial distress also shed light on several aspects of corporate financing and macroeconomic policy. American firms rely heavily on equity despite the substantial incentive to debt finance provided by the deductibility of interest but not dividends. This is often attributed to bankruptcy costs, or more generally to the costs of financial distress (Gordon and Malkiel, 1981). Yet empirical evidence demonstrating that bankruptcy expenses are substantial has been lacking (Warner, 1977; White, 1983; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). The Texaco-Pennzoil case indicates that legal disputes can impose large costs on a firm, and that the indirect effects of conflict on profitability can be substantially greater than the direct expenses of the litigation (Altman, 1984).We suspect that if market valuations of the participants in other large disputes, such as the asbestos claimants and companies, could be found, they would show similar losses in joint value. The evidence suggests that this is almost certainly the case for intercorporate disputes (Engelmann and Cornell, 1988; Bhagat, Brickley, and Coles, 1988; Baldwin and Mason, 1983). Greenwald and Stiglitz (1987) have argued that monetary contractions have substantial supply-side effects. By raising the debt burdens of firms, they interfere with firms' ability to obtain working capital and so make them less profitable. This is quite distinct from any adverse effects that contractionary monetary policies and high interest rates may have on the demand for investment goods. The idea that contractionary monetary policies adversely affect productivity can explain why real wages often fall rather than rise during recessions, and why firms postpone production by liquidating inventories rather than building up stocks during recessions. The Texaco-Pennzoil evidence supports the contention that financial distress can interfere with firms' ability to produce efficiently. Finally, there are important parallels between the Texaco-Pennzoil conflict and the Latin American debt crisis. In both cases, there was an ongoing struggle over a large sum of money. Just as most observers thought it was almost inconceivable that Texaco would pay Pennzoil the full $12 billion jury award, most observers doubt that Latin America will ever pay back the face value of its debt. Just as Texaco's ability to operate efficiently and to undertake profitable investments was impaired by the overhang of its debt to Pennzoil, so too investment in Latin America today is crippled by overhanging debt and the need to meet interest obligations. Just as a negotiated settlement of the Texaco-Pennzoil case raised the market value of both companies, so too an appropriately negotiated writedown of Latin America's debt might benefit both the creditors and the debtor nations. Appendix Table A1 reports the returns of Texaco and Pennzoil and their combined return relative to the Standard and Poor's Composite Oil Price Index. TABLE A1 Returns Relative to Composite Oil Price Index* Change in Market Value ($ million) No. Date Texaco Pennzoil Combined $427.8 (104.7) -$382.9 (293.0) Litigation Events 1 November 19, 1985 -$810.7 (286.3) 25 One possible resolution of the failure of bargaining is the agency problem associated with shareholder lawsuits. Since Texaco's managers may be personally liable for damages the company pays, they might not have an interest in specifying a damage amount (Mnookin, 1987). The proposed settlement, however, indemnified Texaco's directors from any personal liability, and it is not clear why such an indemnification could not have been proposed earlier. CUTLER AND SUMMERS / TABLE A1 171 Continued Change in Market Value ($ million) No. Date Texaco Pennzoil Combined Litigation Events December 10, 1985 December 18, 1985 January 10, 1986 February 20, 1986 February 12, 1987 April 6, 1987 April 12, 1987 November 3, 1987 Total Litigation Events Settlement Events November 19, 1987 December 2. 1987 December 1 1. 1987 December 18. 1987 Total Settlement Events * Standard errors in parentheses. References ALTMAN,E.I. "A Further Empirical Investigation of the Bankruptcy Cost Question." Journal of Finance, Vol. 39 (1984), pp. 1067-1089. BALDWIN, C.Y. AND MASON,S.P. "The Resolution of Claims in Financial Distress: The Case of Massey Ferguson." Journal of Finance, Vol. 38 (1983), pp. 505-5 16. BHAGAT,S., BRICKLEY, J.A., AND COLES,J.L. "The Wealth Effects of Interfirm Lawsuits: An Empirical Investigation." Mimeo, University of Rochester, 1988. COLL,S. The Taking of Getty Oil. New York: Atheneum Press, 1987. CRAWFORD, V.P. "A Theory of Disagreement in Bargaining." Econometrics, Vol. 50 (1982), pp. 607-637. K. AND CORNELL,B. "Measuring the Cost of Corporate Litigation: Five Case Studies." Journal of ENGELMANN, Legal Studies, Vol. 17 (1988), pp. 377-399. FAMA,E.F., FISHER,L., JENSEN,M., AND ROLL, R. "The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information." International Economic Review, Vol. 10 (1 969), pp. 1-2 1. M.H. "Why Is There Disagreement in Bargaining?" American Economic Review, FARBER,H.S. AND BAZERMAN, Vol. 77 (1987), pp. 347-351. GORDON,R.H. AND MALKIEL,B.G. "Taxation and Corporate Finance" in H.J. Aaron and J.A. Pechman, eds., How Taxes Affect Economic Behavior, Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1981. 172 / THE RAND JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS GREENWALD, B. AND STIGLITZ, J.E. "Money, Imperfect Information, and Economic Fluctuations." NBER Working Paper No. 2188, March 1987. JENSEN, M.C. 'LAgencyCosts of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers." American Economic Review, VOI.76 (1986), pp. 323-329. AND MECKLING, W. "Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure." Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 7 (1976), pp. 305-360. MNOOKIN, R.H. "The Mystery of the Texaco Case." Wall Street Journal (November 27, 1987). PETZINGER, T., JR. Oil and Honor: The Texaco-Pennzoil Wars. New York: Putnam Publishing Group, 1987. RUBINSTEIN, Equilibrium in a Bargaining Model." Econometrica, Vol. 50 (1982), pp. 99-1 10. A. LLPerfect H. "U.S. Commercial Banks and the Developing Country Debt Crisis: The Experience SACHS,J.D. AND HUIZINGA, Since 1982." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, No. 2 (1987), pp. 555-601. SCHWERT,G.W. YJsing Financial Data to Measure the Effects of Regulation." Journal ofLaw and Economics, VOI. 24 (1981), pp. 121-159. WARNER, J.B. L'BankruptcyCosts: Some Evidence." Journal ofFinance, Vol. 32 (1977), pp. 337-347. WHITE,M.J. 'LBankrupt~y Costs and the New Bankruptcy Code." Journal of Finance, Vol. 38 (1983), pp. 477488. http://www.jstor.org LINKED CITATIONS - Page 1 of 4 - You have printed the following article: The Costs of Conflict Resolution and Financial Distress: Evidence from the Texaco-Pennzoil Litigation David M. Cutler; Lawrence H. Summers The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 19, No. 2. (Summer, 1988), pp. 157-172. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0741-6261%28198822%2919%3A2%3C157%3ATCOCRA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-8 This article references the following linked citations. If you are trying to access articles from an off-campus location, you may be required to first logon via your library web site to access JSTOR. Please visit your library's website or contact a librarian to learn about options for remote access to JSTOR. [Footnotes] 1 Measuring the Cost of Corporate Litigation: Five Case Studies Kathleen Engelmann; Bradford Cornell The Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 17, No. 2. (Jun., 1988), pp. 377-399. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0047-2530%28198806%2917%3A2%3C377%3AMTCOCL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2 1 The Resolution of Claims in Financial Distress the Case of Massey Ferguson Carliss Y. Baldwin; Scott P. Mason The Journal of Finance, Vol. 38, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings Forty-First Annual Meeting American Finance Association New York, N.Y. December 28-30, 1982. (May, 1983), pp. 505-516. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-1082%28198305%2938%3A2%3C505%3ATROCIF%3E2.0.CO%3B2-3 3 The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information Eugene F. Fama; Lawrence Fisher; Michael C. Jensen; Richard Roll International Economic Review, Vol. 10, No. 1. (Feb., 1969), pp. 1-21. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0020-6598%28196902%2910%3A1%3C1%3ATAOSPT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-P NOTE: The reference numbering from the original has been maintained in this citation list. http://www.jstor.org LINKED CITATIONS - Page 2 of 4 - 3 Using Financial Data to Measure Effects of Regulation G. William Schwert Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 24, No. 1. (Apr., 1981), pp. 121-158. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2186%28198104%2924%3A1%3C121%3AUFDTME%3E2.0.CO%3B2-8 References A Further Empirical Investigation of the Bankruptcy Cost Question Edward I. Altman The Journal of Finance, Vol. 39, No. 4. (Sep., 1984), pp. 1067-1089. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-1082%28198409%2939%3A4%3C1067%3AAFEIOT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-L The Resolution of Claims in Financial Distress the Case of Massey Ferguson Carliss Y. Baldwin; Scott P. Mason The Journal of Finance, Vol. 38, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings Forty-First Annual Meeting American Finance Association New York, N.Y. December 28-30, 1982. (May, 1983), pp. 505-516. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-1082%28198305%2938%3A2%3C505%3ATROCIF%3E2.0.CO%3B2-3 A Theory of Disagreement in Bargaining Vincent P. Crawford Econometrica, Vol. 50, No. 3. (May, 1982), pp. 607-637. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0012-9682%28198205%2950%3A3%3C607%3AATODIB%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Y Measuring the Cost of Corporate Litigation: Five Case Studies Kathleen Engelmann; Bradford Cornell The Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 17, No. 2. (Jun., 1988), pp. 377-399. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0047-2530%28198806%2917%3A2%3C377%3AMTCOCL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2 NOTE: The reference numbering from the original has been maintained in this citation list. http://www.jstor.org LINKED CITATIONS - Page 3 of 4 - The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information Eugene F. Fama; Lawrence Fisher; Michael C. Jensen; Richard Roll International Economic Review, Vol. 10, No. 1. (Feb., 1969), pp. 1-21. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0020-6598%28196902%2910%3A1%3C1%3ATAOSPT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-P Why is there Disagreement in Bargaining? Henry S. Farber; Max H. Bazerman The American Economic Review, Vol. 77, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Ninety-Ninth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association. (May, 1987), pp. 347-352. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-8282%28198705%2977%3A2%3C347%3AWITDIB%3E2.0.CO%3B2-C Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers Michael C. Jensen The American Economic Review, Vol. 76, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Ninety-Eighth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association. (May, 1986), pp. 323-329. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-8282%28198605%2976%3A2%3C323%3AACOFCF%3E2.0.CO%3B2-M Perfect Equilibrium in a Bargaining Model Ariel Rubinstein Econometrica, Vol. 50, No. 1. (Jan., 1982), pp. 97-109. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0012-9682%28198201%2950%3A1%3C97%3APEIABM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-4 U.S. Commercial Banks and the Developing-Country Debt Crisis Jeffrey Sachs; Harry Huizinga; John B. Shoven Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 1987, No. 2. (1987), pp. 555-606. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0007-2303%281987%291987%3A2%3C555%3AUCBATD%3E2.0.CO%3B2-R Using Financial Data to Measure Effects of Regulation G. William Schwert Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 24, No. 1. (Apr., 1981), pp. 121-158. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2186%28198104%2924%3A1%3C121%3AUFDTME%3E2.0.CO%3B2-8 NOTE: The reference numbering from the original has been maintained in this citation list. http://www.jstor.org LINKED CITATIONS - Page 4 of 4 - Bankruptcy Costs: Some Evidence Jerold B. Warner The Journal of Finance, Vol. 32, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Thirty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the American Finance Association, Atlantic City, New Jersey, September 16-18, 1976. (May, 1977), pp. 337-347. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-1082%28197705%2932%3A2%3C337%3ABCSE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V Bankruptcy Costs and the New Bankruptcy Code Michelle J. White The Journal of Finance, Vol. 38, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings Forty-First Annual Meeting American Finance Association New York, N.Y. December 28-30, 1982. (May, 1983), pp. 477-488. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-1082%28198305%2938%3A2%3C477%3ABCATNB%3E2.0.CO%3B2-E NOTE: The reference numbering from the original has been maintained in this citation list.