My Running Hell - Science Museum

advertisement

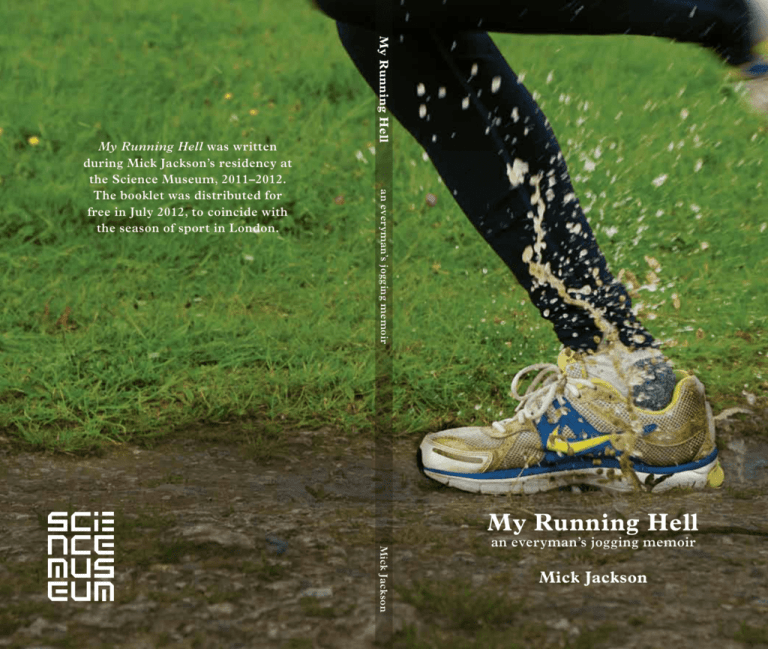

My Running Hell an everyman’s jogging memoir My Running Hell was written during Mick Jackson’s residency at the Science Museum, 2011–2012. The booklet was distributed for free in July 2012, to coincide with the season of sport in London. My Running Hell Mick Jackson an everyman’s jogging memoir Mick Jackson My Running Hell an everyman’s jogging memoir Mick Jackson With illustrations by Jo Riddell and photography by Tim Hawkins A Science Museum booklet I’ve had a couple of bad colds lately. As a result, I’ve missed more runs than I’d care to admit. This is frustrating: getting out on the Downs and stretching my legs is my main means of recreation and pretty much my only form of exercise. Having said that, I do now find that when I get out of bed in the morning I tend not to wince quite as much when my feet make contact with the carpet. Also, the shooting pain in my right knee seems to have eased off a bit. On more than one occasion I’ve caught myself thinking, ‘This lack of exercise is doing me the power of good. If I give it up completely I might one day feel like a human being again.’ * To a non-runner, the idea of propelling oneself forward at anything greater than walking pace for anything longer than the time it takes to, say, catch a bus is quite incomprehensible. There’s a concern, not entirely unfounded, that one is physically incapable of it – that after five or ten minutes one’s heart and lungs will simply explode. To be fair, the first couple of jogs around the local park won’t do much to confound that expectation. Those initial tentative outings will, most likely, be accompanied by a deep-rooted conviction that the whole enterprise is totally ludicrous and that the only sensible option is to stop, tout de suite. It’s bone-shakingly unpleasant while you’re doing it and your muscles ache like mad the following day. For anyone attempting to get into the habit of running the only useful advice I’ve heard is ‘Try not to stop’, because in the first instance stopping is all you want to do. Yet, with a little perseverance, the not-stopping will soon amount to distances and periods of time that, just a few weeks earlier, would have seemed fantastical. 2 3 Running must be unique in its potential for exponential improvement. It’s quite conceivable, for instance, that by the fourth time out you’ll be running twice your original distance and at a much faster pace. Within a month your body will feel significantly different – your calves and thighs transformed into solid blocks of meat. By the third month you may even find yourself contemplating the purchase of a pair of Lycra running tights (truly the moment at which one crosses the Rubicon). Who cares that you look like Max Wall? These things will keep your legs warm in practically any weather. Plus, the improved aerodynamics might trim an extra few seconds off your P.B. 4 5 You will also begin to proselytise. Your metabolic rate, you enthusiastically inform your friends/co-workers/complete strangers, is now markedly higher, which means you have a greater appetite but burn what you consume more efficiently. (You read this online somewhere.) You sleep better. You feel more alive! It might be worth taking a moment to savour this period, not least because it constitutes a sort of runner’s honeymoon. Quite soon, the improvements will diminish in their magnitude; may become merely incremental and come at a greater physical cost. Who knows? The day may come when your times actually falter and, worse, start to slip the other way. * 7 I began running in my late teens, in part, I suspect, because my older brother was already a runner. There must have been other reasons but I can’t quite put my finger on them. Rather unfairly, I imagine my 17-year-old self as being incapable of taking up regular exercise for the same reasons that I run today, which are essentially: (i) a general sense of physical and mental wellbeing, and (ii) some vague notion of calorific offset, whereby, having run in the previous 48 hours, I can drink beer, eat crisps, cake, etc. to my heart’s content. 8 9 My only recollection of me running as a teenager is pulling on my Adidas trainers and my tracksuit bottoms and heading off up the hill past The Dog and Otter, at a time when ‘jogging’ was still considered decidedly cranky and very much an American phenomenon. I ran, on and off, right through my twenties and early thirties, but only began running regularly – i.e. three times a week – about 15 years ago. I’d got out of the habit, was chubbing up and feeling crabby, stolid. My girlfriend, Cath, had taken up jogging and kept suggesting that I accompany her. When I finally consented, male pride necessitated that I run alongside her, despite this being a major effort. (I feel obliged to point out that she’s ten years younger than me.) I doubt if the entire run lasted more than 40 minutes. By the time we got back home I felt like I’d been beaten up by a gang of youths with baseball bats. I went straight up to the bathroom and took a couple of paracetamol. I stared at my contorted, beetroot-red face in the mirror and thought, ‘Either I carry on and it’ll hurt a little less the next time, or I quit now and never bother running again.’ For some reason, I went for Option A. 10 Around this time I started seeing a personal trainer – an arrangement which now seems impossibly extravagant – and was, albeit briefly, a member of a gym. Having sessions with the former and classes at the latter was, I suppose, a way of establishing a routine in which I could attempt to regain some basic level of fitness. But when I felt confident enough with my running to drop the other two I discovered that extracting myself (and my bank details) from the gym was a little like trying to sever ties with the Mafia. So much so that I now consider gym membership to be a modern-day racket of the first order, relying as it does on the complicity of a good proportion of its members, who sign up full of New Year resolution and barely see the inside of the place again – people who fail to cancel their direct debits through guilt at their nonattendance, allied with some vague hope that they’ll get back into it at some unspecified future date. 11 The only essential bit of kit required by a fledgling runner is a decent pair of running shoes (roughly equivalent to six weeks’ gym membership). Everything else is pretty much free. True, you may occasionally require a little willpower. There are times when the prospect of stepping out into the teeth of a hailstorm is a little daunting. What helps motivate me is the fact that, as has been the case for the last eight or so years, I’ll be en route to meeting up with my running partner, Mark. The amount of grief I’d have to endure for a no-show would be too much to bear. 13 Once in a while, if Mark is ill or injured, I’ll run on my own and each time I am amazed at the amount of thinking I can do during a sixor eight-mile run. It’s so eerily quiet! I return to the car brimming with ideas. Some runners wax lyrical about the meditative qualities of their exercise – of finding themselves immersed in a Zen-like zone. The only zone Mark and I occupy is practically militarised – a minefield of sarcasm and ridicule. We wind each other up something rotten. We laugh heartily at each other’s expense. It’s not exactly relaxing, but it does take our minds off the run. 16 17 For as long as I can remember we’ve done a post-work run on Tuesdays and Fridays and a longer run first thing on Sunday morning. Over the years we’ve accumulated a roster of a dozen or so different circuits, of various lengths and proximities to our respective houses, some particularly feared or favoured for the changes in altitudes, some more prone than others to muddiness after rain, and so on. 18 A couple of runs are endlessly adaptable, so that a decision regarding actual duration can be postponed until the last possible minute, mid-run. And it does seem that in recent years when we’ve reached those forks and crossroads we’ve become far more likely to choose abbreviation over extension. To put this in context, there was a time, not that long ago, when I wore a stopwatch and we would endeavour, to some degree at least, to improve on our previous best. For two whole winters we did our evening runs out on the Downs by torchlight. We’d enter races – 10ks, 10-milers and even the occasional halfmarathon. There’s a race, renowned locally as a bit of a lung-buster, which though short manages to incorporate two separate ascents of the scarp (the steep side) of the Downs. I can feel my heart beginning to race at the very thought of it. Halfway up the second of those devastating inclines I have been gripped by the same dark thoughts as the jogger out for his/her first time. That this is too much. That this isn’t natural. That very soon there will be profound physical consequences. 19 Not any more. We seem to be done with pushing the envelope. The last race Mark and I ran together was probably three years ago. These days we’re happy if we can complete a run without pulling a muscle. We’ve become plodders – ‘joggers’, as opposed to ‘runners’ – stopping at every gate and stile to stretch our hamstrings, and forever fretting about whatever niggles and twinges currently threaten to cramp our style. 20 21 The arrival, in recent years, of my son and daughter has been an unparalleled joy and, I like to think, the making of me as a man, but there’s no denying it has rather buggered up my running. Some mornings I feel like I’ve done a marathon before I drag back the curtains and, logistically, there’s no getting round the fact that 5pm – our weekday rendezvous – coincides with feeding time at the monkey enclosure and the beginning of the gradual herding of children up to bed. You may guess at how accommodating Mark has been in this regard. 22 Also, I don’t remember anyone warning me how a child who starts attending nursery will bring home all manner of bugs and viruses (which is odd, since there’s nothing one parent enjoys more than telling parents of younger children about the misery awaiting them). You’d imagine a ‘nursery bug’ as a teeny thing, easily squished underfoot by a man approaching, or possibly in the process of passing, his prime. But these things are vicious, omnipotent critters, capable of laying a man low for weeks, even months, at a time. This too is almost bound to have a bearing on one’s fitness regime. But perhaps it’s wrong to have my children bear full responsibility for my dip in form on their young shoulders. Because if I think back, a certain conservatism had begun to creep into my running at least a year before they arrived on the scene. In fact, I can trace it back to a particular incident when, one Sunday morning, having run a mile or so west along the Downs from Devil’s Dyke, I made a heroically reckless descent down a 1-in-2 slope, reaching the sort of speed where you get a little giddy and ever so slightly out of control. Either I tripped over a root or my foot landed in a hollow. The resulting ‘crack’ could be heard echoing across the Weald as far as Gatwick Airport. I was travelling with such momentum that I had to hop for about 30 metres before coming to a halt. To say that I’d gone over on my ankle feels mightily inadequate. When I finally stopped I couldn’t quite believe that my foot was still attached to my leg. With Mark’s help I hobbled to the bottom of the path. Then, perhaps out of sheer relief at there being no apparent fracture, I proposed that we carry on running, to give it a bit of a stretch. What peculiar behaviour. Perhaps my head was swimming with adrenaline. Either way, within a minute I began to appreciate the folly of this decision. I stopped and took my sock and shoe off. My ankle looked like a full hot water bottle – seemed to be swelling before my very eyes. In fact, within seconds it had swollen to such gargantuan proportions that I couldn’t get my shoe back on. 24 25 When it comes to pulls and strains, runners are particularly fond of the acronym RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation) as the most effective treatment, but you can RICE some injuries all you like, you’ll still have a foot with what looks like a goitre stuck to the side of it. The swelling didn’t go down for six weeks and it was at least a month before my physio, Nik, could lay a finger on it without me squealing like a little girl. (No disrespect to little girls.) When I did finally return to my running, my ankle rattled, despite being strapped up like a joint of brisket and I lived in mortal fear of repeating the injury. It’s amazing quite how many roots and hollows there are out there when you start looking. Even now, all these years later, if my foot comes down on uneven ground and threatens to go over I have flashbacks and am reduced to a quivering wreck. 26 27 Every twist and sprain comes with its own price tag, roughly calculable by the number of visits required to one’s personal practitioner, at around £45 a pop. On top of that, for the last six years I have been seeing a lady footdoctor about the pronation on my left foot. The insoles she cooks up for me in what looks suspiciously like a microwave are by no means cheap, but they do appear to have stopped my left calf seizing up whenever I attempt to run for more than an hour at a time. To be fair, I’ve been seeing an osteopath since way back in the 1980s, but these days he seems to be dealing more with runningrelated problems than anything to do with my appalling posture (unless my poor posture is the result of the fact that I now run with a bit of a limp). It’s all money well spent, of course. It’s just that I’d much rather spend the money on other things, such as food or drink, or paying off the mortgage. Or toys for the little ones. * 30 31 A couple of months ago I was rooting about in the attic and found an old scrapbook. On the cover are the words ‘OLYMPICS’ and ‘1972’, written in the bubble letters that were de rigueur on every schoolchild’s jotter and pencil case at the time. I vaguely remember sitting at the kitchen table and creating the five Olympic rings by tracing round egg cups, then colouring them in with felt-tip pens. The whole venture, I imagine, was probably instigated by my parents, but I’d like to think that it was in response to some enthusiasm I’d expressed for the Games. 32 33 The first third of the scrapbook seems to have been filled quite without discrimination. So for instance there is a half-page photograph of the newly opened volleyball hall ... stories of romance blooming between competitors (‘WE’LL WED, SAY STARS’) ... alongside articles about showjumping, judo and yachting. As a result I’d pretty much filled the book before the second week of athletics. The extra cuttings are tucked inside the back cover in a great wodge. By then it was probably clear that Great Britain wasn’t about to top the medals table (a bitter pill for any newly patriotic youngster) and the thought of having to buy another scrapbook and get out all the egg cups and felt-tip pens again probably just seemed too much of an effort. 34 As one might expect, there are plenty of clippings about Mark Spitz (‘SPITZFIRE’ ... ‘SUPER SPITZ’ ... ‘THE SPITZKRIEG’), Kip Keino and Mary Peters, the Northern Irish athlete who won a gold medal in the pentathlon. But, in between, there are curious bits and pieces I’ve no memory of collecting, such as a tiny article concerning Jesse Owens’s return to Germany, 36 years after winning four gold medals in Berlin in front of Adolf Hitler (where he rather confounded the Nazis’ claims about the superiority of the Aryan race). The whole thing, by definition, is a bit of a hotchpotch and I doubt I managed to read half of the articles before pasting them in for posterity. But one athlete is ubiquitous above all others – David Bedford, the 5000 and 10,000 metres runner, who was my first real sporting hero, despite him having what can only be described as a disastrous Games. 35 36 37 It’s hard to convey now what an unlikely figure Bedford cut in the early 1970s. With his long hair, Zapata moustache and occasional bandana, he looked more like a rock star than a middle-distance runner. Pre-race, he’d stroll around as if he’d just partaken of some colossal bong, but his running style was far from effortless. He pounded away at the track with his elbows jutting out, and something of the nodding-dog head movement more recently associated with Paula Radcliffe. His main strategy was to ramp up the pace from early on, in order to establish a gap of such proportions that those runners who actually had a sprint finish wouldn’t be able to catch him on the last lap or two. 38 39 He was a bit of a scruff – a phrase I’d already heard used to describe my own appearance – but wasn’t exactly lacking in self-confidence. He wore his (red) socks rolled right down to the ankle and would chat to the other runners, mid-race, sometimes to their profound irritation. I didn’t appreciate it at the time but he also stirred up a good deal of antipathy off the track, not least in the press. In one of my cuttings Bedford is compared, to his detriment, with the much more ‘gentlemanly’ athlete David Hemery, who was also competing in Munich and nearing the end of his career. The implication was that Bedford, in attitude as well as appearance, was a lout. Or to put it more bluntly, he wasn’t sufficiently well bred. 40 41 All that interested me was that he looked cool and regularly whupped the competition, so when my family and I sat down to watch the 10,000 metres final, I fully expected him to walk away with the gold. But from the moment the runners filed out onto the track it was clear that something was seriously amiss. The first close-up of Bedford revealed that his Frank Zappa locks had been shorn into a sickeningly conformist short back and sides. Had he burst a blood vessel in the semis? Or, worse, had someone got to him with a pair of clippers while he lay in his bed at night? Either way, I had been betrayed, along with all my fellow scruffs. The ‘Jesus of Nazareth’ image had been discarded in favour of someone who looked like he was on his way to an interview at the Midland Bank. 42 43 I wouldn’t read Milton’s Samson Agonistes for at least another five years, but even a 12-year-old can read the writing on the wall. Dave’s long hair was part of what made him so exceptional. It somehow sucked up extra oxygen and delivered it directly to his legs. Now, all I could do was sit and watch Fate follow its course. Four laps into the race, Bedford attempted to push on but found his resources wanting. There would, it seemed, be no slow annihilation of the other runners. Worse, in what I remember (wrongly, as it turns out) as the penultimate lap, Lasse Virén, a Finn, and Emiel Puttemans, a Belgian, left Bedford and everyone else standing, as if the two of them had just joined the race from the sidelines and were having their own 800-metre sprint to the line. 44 Bedford limped in sixth. I was devastated – by the lack of medals, but also the betrayal regarding the hair. In one cutting in my scrapbook, Ian Wooldridge of the Daily Mail seemed positively delighted, as if it was a comeuppance, long overdue. Dave’s sin, apparently, had been not just to fail, but to do so after so much un-British bragging. To cap it all, following the race Bedford left the track at the soonest opportunity, pushing away the film cameras intent on capturing his distress. It’s still not clear to me whether Wooldridge’s objection was to the fact that Bedford displayed such distress in the first place or that he wasn’t inclined to share it with the rest of the world. * 45 My only other real sporting hero – the only other man with whom I felt some unshakable connection – was Steve Ovett, who ran in the 800 metres and 1500 metres at the Moscow Olympics, eight years later. If Bedford looked like he’d just completed a session on The Old Grey Whistle Test, Ovett had, to me at least, something of the Alf Tupper to him (the working-class runner from the Victor comic, renowned for eating fish and chips on his way to the track). Of course, I was doing both Ovett and Bedford a huge disservice by imagining that they didn’t have to train as hard as other athletes, but it fitted my romantic ideal of them as innately and self-assuredly brilliant. Ovett’s rival at the time, Sebastian Coe, put me in mind of the boy at my school who not only captained the football team, but also the first XI cricket team. Steve Ovett reminded me of, well, me. 46 47 Strangely, my memories of Ovett winning the 800 metres final and losing to Coe in the 1500 metres in 1980 are far less vivid than Bedford’s efforts in Munich – strange because they’re more recent, but also because Ovett actually won a gold. In full flight, Steve Ovett could look utterly manic. His eyes bulged out of their sockets; his skull seemed to press at his flesh. Seb Coe was often criticised for being a tad too slick and good-looking. But next to Ovett, Coe couldn’t help but look drop-dead gorgeous. Pretty much any athlete would have done the same. Curiously, watching footage of those races now, Coe seems a little hard done by. When he raced he was the model of grim determination, running so hard that his chest sometimes seemed in danger of leaving his head bobbing in its wake. 48 49 It’s only now, decades later, that I understand that what appealed to me about both Ovett and Bedford was the idea of them as ‘outsiders’: men who against all odds had forced their way onto my TV screen. The fact that the press didn’t particularly warm to them did nothing but confirm my reasons for idolising them. * 50 51 I didn’t appreciate that Ovett was born and raised in Brighton until I moved there in the mid-1990s where, much to my delight, I found that a statue had been unveiled in the great man’s honour near the entrance to Preston Park. Even more gaunt – practically Giacomettian – than in the flesh, Statue Steve appeared to be haring out of the bushes, having failed to pay for an Eccles cake in the nearby Rotunda Café. The park is a five-minute jog from my front door and long before Mark and I became running partners I would regularly pad around the park’s perimeter with all the other puffers and panters. When I passed Steve’s statue I would give him a little nod, and even after Mark had joined me, I would find myself offering the statue a silent, inward genuflection. Statue Steve took on near-holy status, with one hand raised in benediction upon all who jogged in his midst. 52 53 Then, about four or five years ago, I was running round the park and went straight past the spot where Steve should have been, without spotting him. I assumed I hadn’t been paying attention, so the next time round I had a proper look. Statue Steve, it seemed, had done a runner. I stopped and stepped right up to the rosebeds. Just above the soil stood a solitary Ovett foot – the one Steve was taking off from. Like an animal caught in a trap, Statue Steve had chewed off his own foot, rather than spend another year locked to the plinth in mid-sprint. Either that or someone had come along at dead of night with an angle-grinder and cut straight through his ankle and bundled him into the back of a van – someone who knew the current price of scrap bronze. 54 55 The theft generated quite a bit of publicity, but since there was no CCTV footage of the incident there were no leads to follow up. A year or two ago I noticed a tiny piece, no more than 12 lines long, in a national newspaper which described in rather gory detail how some of Steve’s ‘body parts’ had been recovered at a Brighton address, but as far as I know Steve’s torso has never been recovered and no-one was ever charged with his theft. Thankfully, the Real Steve is still soaking up the sun in Australia, having emigrated there in the 1990s. Whenever he pops up on the television to do a little commentary (something I sincerely hope that he’ll be doing this summer), or to be quizzed, yet again, about his great rivalry with Sebastian Coe, he looks more relaxed than he ever did in the ’80s. Perhaps it’s because he’s now on the outside looking in, and that suits him better. Or perhaps it’s the fact that he’s not having to do all that running. As a fellow runner, I’m only too aware how it can take its toll. * 56 57 A couple of Tuesdays ago I went along to the Withdean Athletics Stadium in north Brighton, to take part in a little ‘speed training’. Sam Lambourne has been running the sessions for years. You don’t have to be especially speedy to take part – just a regular runner. Men and women of all ages and abilities turn up. The idea is that you sprint for a prescribed distance – say, 200 metres – then stroll for the next hundred to get your breath back, before sprinting again. The final session of the evening is a 1500 metres. The last time I’d run on the track I’d achieved what I considered to be a quite respectable time. As I pulled on my running shoes I thought it just about possible that I might achieve a similar finish. I keep meaning to check the sort of time needed for Olympic qualification. Who knows, perhaps if I lay off the beer and crisps, and some younger athlete twists his ankle or picks up a bug, I might get a late call-up. 58 59 It can take me a little while to warm up these days – sometimes an entire run – so I did a gentle circuit. Then another one, just to be sure. We started the sessions and I completed eight sets of 200 metres without particularly pushing myself. It was, I felt, important to keep a little something back for the 1500 metres at the end. But at the start of the 400-metre sessions I thought I’d better start increasing my pace a tiny bit, if only to avoid my entire system going into a state of shock when I eventually made some real demands on it. 60 61 I stepped up to the line and leant forward, just like Dave and Steve did all those years ago. Sam clapped his hands to replicate the sound of a starting pistol and we were off – all 15 of us. We raised our heads and saw the track open up before us. For the briefest moment we were running in slo-mo, like those blokes in Chariots of Fire. 62 63 I’d taken about five steps when I was gripped by some painful, all-encompassing impediment. My first thought was that one of my fellow runners had clipped my ankle. My second thought was that a sniper had taken me out from the stands. I hobbled to a halt as the other runners flew past me. I slumped onto my backside and was still scanning the empty seats for my would-be assassin when I realised that the spasm in my calf was basically a pulled muscle. The same one I’ve pulled ten times before. The only important thing, I felt, was to drag myself out of sight before the runners completed the circuit. Otherwise, I’d be obliged to explain how I’d somehow managed to pull a muscle whilst practically standing still. I got to my feet and limped off towards the nearest exit. Back in my car, I dug my thumb into my leg and could feel a knot the size of a golf ball buried deep in my calf. 64 65 I waited a clear ten days before seeing Nik, my physio, vainly hoping that it might get better on its own. He gave it a bit of a rub and told me that it’ll need at least another couple of sessions to get it moving, and probably an additional three or four weeks before I can run again. In the meantime I’ve been given a list of stretches and exercises to help it get better. If I didn’t have a job (and children) I might have a chance of completing them. As it is, I go up on my toes while I’m waiting for the kettle to boil at the office, and if I have the energy I do a few stretches in the evening lying on my back in the living room. If I position myself quite carefully I can watch the telly while I pull my knee up to my chest. I should endeavour to make myself comfortable. At this rate I may be watching the Olympics from down there. 66 68 69 The original bronze of Steve Ovett was made by Pete Webster. Pete has been commissioned to create another statue of Steve Ovett, which will be located on the seafront by the finish line of the Brighton marathon. It is due to be unveiled in late July 2012. Illustrations by Jo Riddell Photography by Tim Hawkins Designed by James Frankis and Lyn Modaberi Commissioned by Hannah Redler and Ruth Fenton, Science Museum Arts Projects Copy-edited by Lawrence Ahlemeyer Proofread by Gordon R Hooper Images of Max Wall and Steve Ovett provided by Getty Images Image of David Bedford provided by the Press Association Image of the Steve Ovett sculpture provided by Pete Webster © Mick Jackson 2012 Mick Jackson asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this book Printed on FSC certified 100% recycled paper. Printed with vegetable inks. 72 73