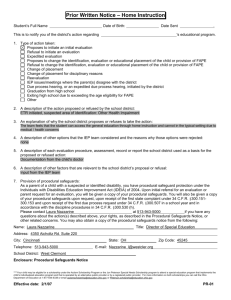

due process disaggregation

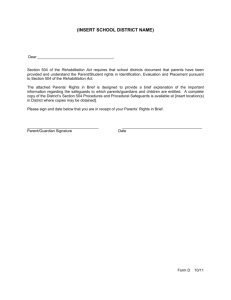

advertisement