Deviant Behavior and Social Control

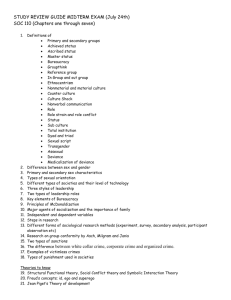

advertisement