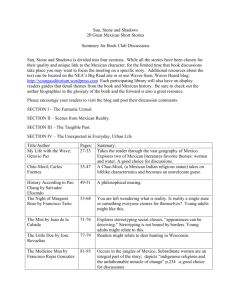

Copyright by Laura Angelica Trujillo-Ball 2003

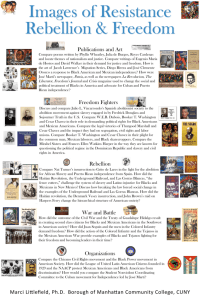

advertisement