Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy

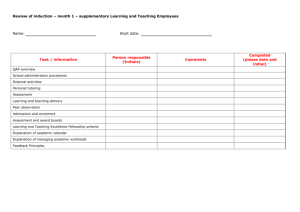

advertisement

This article was downloaded by: [University of Bath] On: 03 January 2014, At: 01:39 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcri20 Strengths of Public Dialogue on Science‐related Issues a a Roland Jackson , Fiona Barbagallo & Helen Haste b a British Association for the Advancement of Science , London, UK b Department of Psychology, University of Bath , UK Published online: 19 Aug 2006. To cite this article: Roland Jackson , Fiona Barbagallo & Helen Haste (2005) Strengths of Public Dialogue on Science‐related Issues, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 8:3, 349-358, DOI: 10.1080/13698230500187227 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13698230500187227 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sublicensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http:// www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy Vol. 8, No. 3, 349–358, September 2005 DEBATE Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 Strengths of Public Dialogue on Science-related Issues ROLAND JACKSON*, FIONA BARBAGALLO* & HELEN HASTE** *British Association for the Advancement of Science, London, UK **Department of Psychology, University of Bath, UK RolandJackson Taylor 8302005 roland.jackson@the-ba.net 00000September & Francis 2005 Critical 10.1080/13698230500187227 FCRI118705.sgm 1369-8230 Original and Review Article (print)/1743-8772 Francis ofGroup International Ltd Ltd (online) Social and Political Philosophy ABSTRACT This essay describes the value and validity of public dialogue on sciencerelated issues. We define what is meant by ‘dialogue’, the context within which dialogue takes place in relation to science, and the purposes of dialogue. We introduce a model to describe and analyse the practice of dialogue, at different stages in the development of science, its applications and their consequences. Finally, we place the practice of dialogue on science-related issues in relation to the wider political process and draw out implications for scientists in particular. KEY WORDS: dialogue, science, communication Introduction Bill Durodié, in his paper ‘Limitations of Public Dialogue in Science and the Rise of the New ‘Experts’ (2003) sets out his analysis of ‘confusions’ and ‘limitations’ of current thinking and practice. The paper reads rather more as a polemic, perhaps, than as a serious in-depth analysis, but nevertheless this is a challenge to those who do believe in the value and validity of public dialogue on science-related issues, and it should be answered. We present here an outline of the context, purposes and practice of public dialogue, its strengths and weaknesses, and its linkage to the wider political as well as the scientific, process. We introduce a model which we believe to be helpful in analysing different processes of dialogue; their appropriateness at particular stages in the development of science and its applications, and in the emergence of associated issues. Correspondence Address: Dr Roland Jackson, The British Association for the Advancement of Science, Wellcome Wolfson Building, London SW7 5HE, UK. Email: roland.jackson@the-ba.net ISSN 1369-8230 Print/1743-8772 Online/05/030349-10 © 2005 Taylor & Francis Group Ltd DOI: 10.1080/13698230500187227 350 R. Jackson et al. Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 Dialogue Defined The extensive use of the concept of ‘dialogue’ can be traced back to the seminal House of Lords Science and Technology Committee Report ‘Science and Society’ (House of Lords 2000). Around this time there was a growing critique of the approach described as the ‘public understanding of science’ which had emerged from the 1985 report of the Royal Society committee chaired by Sir Walter Bodmer (Bodmer 1985). The critiques arose from a recognition that focusing on the public’s understanding of science tended to imply ‘a condescending assumption that any difficulties in the relationship between science and society are due entirely to ignorance and misunderstanding on the part of the public; and that, with enough public-understanding activity, the public can be brought to greater knowledge, whereupon all will be well’ (House of Lords 2000, paragraph 3.9). This is now frequently referred to as the ‘deficit model’. With increasing appreciation that a genuine two-way communication is needed in the discussion of science-related issues the language currently used focuses on ‘public engagement’ and ‘dialogue’. However although the language has changed, the sentiments of the House of Lords report have not been readily endorsed. Sociologist Brian Wynne has stated that the deficit model is more an ‘ideological construct than a research method’ (Wynne 1993: 322) and it is not simply avoided by changing the format of public engagement activities. There is an agreement that the ‘public understanding of science’ will not ease ‘public concerns’ or ‘increase trust’ yet there are alterations of this phrase – public understanding of peer review and public understanding of scientific research process – which still embrace the deficit model approach. Are we seeing a revenge or reinvention of the deficit model in many dialogue activities? Dialogue is not primarily about providing a platform for scientists to explain to the receptive layperson how the world works. It is instead a context in which society (including scientists) can address the issues that are arising from new developments in science. Science should not be expected to have sole responsibility for the future of such developments; there is a responsibility to society to involve all citizens in decisions to the extent that this is possible. Dialogue does not remove authority or expertise from science; it locates scientific developments in a wider social context and enables the inclusion of a wider range of relevant expertise with regard to the implications of such developments. The intended meaning of ‘dialogue’ in the House of Lords report, defined for our purposes here, is that dialogue is an open exchange and sharing of knowledge, ideas, values, attitudes and beliefs between stakeholders (e.g. NGOs, commercial organisations, interest groups), scientists, publics (e.g. members of the general public, farmers, consumers) and decision-makers (local, regional and national). Context of Dialogue We would argue that Durodié has misled himself up a blind alley by setting his context as ‘dialogue in science’. This mistake leads him to imply that those with Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 Public Dialogue on Science-related Issues 351 whom he is taking issue would somehow believe that the validity of scientific knowledge itself can be democratically decided. What can and should be democratically decided is the kind of future we create with the possibilities of science through technology and engineering, where to put our priorities and how science and its applications and implications should be governed and managed. ‘Dialogue in science’ happens between practising scientists and is a key part of the process of establishing reliable scientific knowledge. Dialogue on science-related issues, which is our concern and focus, needs to take into account established scientific knowledge and its inherent uncertainties but also to recognise the other relevant factors in the situation. The aim of dialogue in this arena is not to somehow set public opinion as equal to scientific evidence but to recognise that aspects other than the scientific are relevant and indeed essential for considering what we want science and technology to do for us. First, non-scientists may possess relevant local knowledge that specialist scientists do not at any point in time, e.g. the farming community in relation to Chernobyl (Wynne 1989, 1992; Michael 1996, ch. 6), farm-worker experiences with 2,4,5-T pesticide (Irwin 1995), patients’ knowledge of new genetics (Kerr et al. 1998) and the management of BSE (Jasanoff 1997). Second, social and ethical factors are relevant in addition to scientific information. A lack of scientific knowledge does not inhibit citizens from discussing ethical stances of individuals, questions of equity and access, and trust in the regulatory process. These ‘lay values’ – which may also indeed be shared by scientists – should indeed be part of the wider political debate. The effective citizen draws on numerous sources for her or his moral stances, and sense of political engagement. Where moral positions or issues of power and responsibility impinge on scientific development, it is the obligation of both scientist and layperson to explore this intersection, and negotiate and clarify areas of incomplete knowledge where appropriate. Durodié argues that the public debate should be separate from the scientific debate. However, attempting to decouple them from public discourse about science and its implications will tend to lead to the dislocation of scientists from the interests, concerns and knowledge of public stakeholders. This does not marginalise scientific evidence and we cannot imagine the many robust individuals at the forefront of science being ‘demoralised’ by this process, as Durodié claims they will be. Purposes of Dialogue Everyone is in favour of dialogue, but what is it for? The danger – and this is a valid point that Durodié raises – is that ‘public dialogue allows the authorities to claim we were all consulted should things go wrong in the future’ (Durodié 2004: 88). Indeed, if decision makers do view dialogue and consultation as purely cosmetic, if they ‘talk the talk’ but do not ‘walk the walk’ then public cynicism and mistrust will surely follow. The House of Lords report clearly sees the purpose as developing mutual trust between scientists and the public and securing science’s ‘licence to practise’, Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 352 R. Jackson et al. acknowledging that this is probably best done through dialogue: ‘Policy makers will find it hard to win public support on any issue with a science component, unless the public’s attitudes and values are recognised, respected and weighed along with the scientific and other factors’ (House of Lords 2000: para 2.66). We see three broad categories of purpose for dialogue: increasing democracy by promoting open and transparent decision making; greater trust and confidence in the regulation of science and the decisions taken; and that better decisions will have been taken. These three categories are based on Daniel Fiorino’s arguments for public participation in environment decision making (Fiorino 1990). The first purpose, increasing democracy, refers to extending the range and number of people empowered to talk about science issues, improving public capability to influence local and national science-related plans and proposals. By making science more accessible through effective communication of scientific ideas and developments, and engaging and motivating lay people in an active understanding of scientific knowledge in a social, environmental and practical context, it is assumed that they will feel able to contribute to public discussion about scientific policy. This is the normative view of public engagement. Dialogue should serve a second purpose of building greater trust and confidence in the regulation of science and in scientific institutions. Through consultation and greater transparency about decision making in relation to new developments, and recognising and acknowledging public interests and concerns, dialogue will reduce conflict between the science community, the regulators and publics. The second purpose of dialogue is an instrumental view. Thirdly, dialogue should improve the quality of policy decisions by including a broader range of knowledge and considering how to develop science in ways that benefits society. This includes recognising the role of relevant expertise which may lie outside the boundaries of ‘academic’ science, including local knowledge or practical experience. The decisions are taken not just to improve the reputation of science or that of those making the decisions, but to improve the quality of our life. This is a substantive perspective. Throughout all of this is the underlying need for scientists and policy makers to acknowledge public views and opinions as legitimate. Practice of Dialogue We take it as axiomatic that dialogue will only be effective if all stakeholders and lay publics can participate. In that respect, we would consider Durodié’s assertion that ‘the public is patronised by having to make science more “accessible” in order to be “inclusive”’ to be rather extraordinary. It seems a most strange assumption, that we should not attempt to discuss science and its issues in ways that are suitably accessible to people, framed in ways that are relevant and interesting. We believe that members of the public are not incapable of having a sophisticated conversation about issues arising from contemporary science, such as GM foods and stem cell research. If only the ‘experts’ can take part, on terms they have decided themselves, Public Dialogue on Science-related Issues 353 Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 it would be no surprise if the public at large were exceptionally suspicious and mistrusting of the outcomes. The whole point about dialogue is to find the common language and understanding, and to inform the ways in which all people, scientists and non-scientists alike, think about the priorities, directions, implications and consequences of science. The views and expertise of non-scientists with a legitimate interest in the issues are all relevant here. Social scientists can and should offer valuable specialist expertise particularly on likely social, political and economic consequences. Dialogue needs to go hand in hand with the wider political process (such as we have seen over stem cells in recent years). There needs to be challenge to understanding, on all sides, but surely in terms that enable the challenge to be understood? A Model for Engagement There is increasing realisation in the UK at the moment that it is important to communicate with the public at early stages in developments, and indeed as the research and development agenda is being shaped, if that is possible. If the public is not conscious or involved at early stages there is a risk of a strong reaction later if the outcomes of research or its applications are presented and found to be at odds with the values or expectations of stakeholder groups and publics. If we imagine a cycle (Figure 1), starting from the choice of research area and leading through into discovery, application and visible consequences (which then of course feed back into choices of more research) it seems evident that different models of engagement are suitable at different stages. In general, where the research is in early stages and especially where it is leading-edge and complex and there is great scientific uncertainty about outcomes, benefits and risks, small scale deliberation between scientists and others will tend to be most appropriate. Once applications and consequences are more evident, either anticipated or already realised, mass participation methods become more relevant. Of course, a range of communication processes is required throughout the entire cycle for different reasons, often running in parallel. From the public perspective the critical factors are ones of trust, control, responsibility, equity, access, benefits and consent. Are the people, institutions and processes responsible for developments trusted? Is there public confidence that issues of potential liability have been addressed if things go wrong, and responsibility is identified? Has the public, in the broadest sense, given implicit or explicit consent? Will poor and rich countries have equal access to the applications of science? Referring to this we now describe three recent examples in the UK of engagement activities at different stages in the process. Figure 1 When and how should public engagement take place? (The oval represents the social environment within which we live) Cognitive Systems The first relates to new developments in cognitive systems, bringing together leading edge research in computer science and neuroscience. In terms of the model 354 R. Jackson et al. ‘UPSTREAM’ direct communication/deliberative setting the research agenda consequences publics Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 decision-makers stakeholders scientists research applications ‘DOWNSTREAM' mass communication Figure 1 When and how should public engagement take place? (The oval represents the social environment within which we live). it is very much ‘upstream’, in other words early in the process of discovery and development, as the research agenda is being defined. The Foresight team from the UK government’s Office of Science and Technology had decided to focus on this area, bringing together leading researchers from various disciplines to look at its future potential and possible fruitful new areas of research. We wanted to see if nonscientists, representative of those with an interest of science but not actively finding out about it, could sensibly discuss options and priorities with the researchers, and generate some common language for discussion, despite being unfamiliar with the detail of the leading-edge science. In other words we wanted to establish some sort of more anticipatory form of technology assessment which might, if introduced more generally, be expected to take into consideration a broader range of opinions rather than just scientific expertise. Perhaps unsurprisingly we found that if the discussion was organised around questions such as benefits, concerns and moral issues both the scientists and the non-scientists could have very constructive discussion. The findings indicated that scientists and the public participants shared the same dreams, hopes and fears for these new technologies. Altogether it was very positive and we hope will be a model to engage many other scientists with the process in other fields. Public Dialogue on Science-related Issues 355 Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 Stem Cell Debate The second example is the debate about stem cell research recently in the UK, which led to our current legislation on therapeutic cloning. In terms of the model this is at the stage of emerging applications, so that people could discuss the consequences they imagined and those they wished to see or not to see realised. There was extensive and well-informed debate in both our chambers of Parliament, and the discussion prior to those debates engaged a substantial number of people. This happened through the mobilisation of, for example, patient groups and medical research charities, and through extensive and balanced reporting in the media. The consequence was a well-informed set of members of Parliament who were able to hold a rich debate. It is held up in the UK as an example of success. This was perhaps due to a combination of the involvement of patient groups and the fact that the stem cell debate followed many years of public discussion about related issues in the UK. This started with a widely-debate report, the Warnock report in 1984, produced by Baroness Warnock who was not seen to be a member of the scientific community but had substantial public reputation. Regulation and legislation were introduced gradually, so that by the time the stem cell issue became live the ground was well prepared. GM Nation The third example relates to the debate about the introduction of genetically modified crops in the UK. In terms of the model this is further ‘downstream’ when applications are already very visible or perceived to be. This issue generated enormous debate and indeed opposition in the UK, particularly from well-organised pressure groups and there was extensive media reporting, often of the ‘Frankenstein foods’ variety. The issues came to a head over the need for the UK government to take decisions about whether to license the growing of genetically modified crops and in the context of the dispute between the United States and Europe. From the point of view of the UK public, although there is evidence that concerns were overstated by pressure groups and in the media, there is little doubt that the issue of GM crops seemed to have appeared quite suddenly, without wider debate, and that their introduction was being promoted by a large US corporation (Monsanto) whose motives many questioned: it seemed that the proposed crops would be of financial benefit to the company but the wider public benefits were not obvious when set against the possible risks and the unknowns. Questions arose about food safety and environmental effects, including cross-contamination and the impact on organic produce, and when many of these could not be clearly answered to general satisfaction the concerns remained. The UK government should be given credit for orchestrating a wider debate, and implementing farm scale evaluations, but it was probably too late, with positions entrenched. As a consequence in particular of the problems with GM technology, policymakers in the UK are now more sensitive to the need to encourage open and Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 356 R. Jackson et al. informed public discussion at earlier stages and to encourage scientists themselves to be aware of this need to consider issues and implications, including with the public. There is certainly concern that nanotechnology could become controversial unless handled correctly and that socially-beneficial applications could therefore be missed and potential businesses driven elsewhere. The UK government has commissioned the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering to produce a report on nanotechnology and its implications, so that the scientific and engineering community has had the opportunity and incentive to think about these wider issues. We believe it is important that discussion then takes place in ways that address factors of public importance. The public is likely to want to see that the issue of who controls the technology will be discussed, and be confident that regulation balances societal and consumer benefits with rewards to businesses exploiting the technologies. It will want to ask about ethical implications (especially regarding health and the human body), equity of access to technologies, long-term effects, known and unknown areas of consequences, and impact on quality of life and our environment. There is increasing realisation, but not yet widespread enough, among scientists and policy-makers that they must interact positively and responsively to the public on these terms, rather than criticise the media or make patronising statements about public ignorance. The science alone, and what we know and don’t know in scientific terms, is but a part of the whole debate. Relationship to the Wider Political Process Durodié appears to wish for a past golden age when experts were experts, authorities were automatically respected by tradition and everyone knew their place. It was obvious who to trust. The world is not like that, if it ever was, whether we wish it or not. Trust, and the recognition of uncertainty and the limits of knowledge, will develop from open discussion among all stakeholders, over a long period. Those of us committed to public dialogue in science-related issues recognise this and seek ways to help it to happen. We complement, but do not replace, the wider political process. Durodié makes much of the need for mass political engagement and a broader social vision to somehow wash away the ‘self-doubt and cynicism’ he perceives all around him. We see dialogue on science-related issues as a part of wider engagement. At times, as we have described above, when the process of discovery and invention is in its early ‘upstream’ phase, dialogue will tend to be small-scale and deliberative. Groups of people will come together to establish simply how they can have a conversation which will inform interested publics early on about some of the potential issues. This will enable scientists and decision makers to sense and respond to public interests and concerns, establishing how to talk about what they are doing in ways that will promote fruitful exchange of views rather than the establishment of entrenched opposing positions. At other times, when ‘downstream’ applications and consequences are more evident, and especially when significant regulatory and legislative aspects are under examination, dialogue will take place on a wider stage and integrate with the formal political process. If the ground has been Public Dialogue on Science-related Issues 357 set ‘upstream’ in advance, the discussion is likely to be so much more constructive. There is thus a spectrum of engagement, from small-scale to mass involvement, both elements of which are helpful to building a broader social vision about the type of relationship we want with science and technology. Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 Implications and Conclusions The best way to address the fear of change which Durodié asserts is for the experts and the decision-makers to come out into the open as many, though not enough already do, both to challenge and to be challenged by complementary knowledge and perspectives. That does indeed imply the need on behalf of scientists to listen and respond; and in the words of Dr Neal Lane, the US president’s assistant for Science and Technology, described in the House of Lords Report (House of Lords 2000: para 3.11) they should see themselves as ‘civic scientists’ that is, as scientists ‘concerned not just with intriguing intellectual questions but also with using science to help address societal needs’. The culture of the scientific community, on the whole, does not give this high priority. It is well acknowledged that scientists who do spend time on public engagement, directly and through the media, do not in general find it to be career-enhancing, given the pressures of systems such as the Research Assessment Exercise, although a few well-known scientists do receive public recognition through mechanisms such as the Royal Society Faraday Award and the Science Book Prize Those concerned to promote productive discussion between scientists, decisionmakers and publics do not do so to ‘restore the primacy of science’, which seems to be Durodié’s aim, but to ensure that science and its applications can advance with public consent, contribution and active support, shaped through varied and open discussion of what society wants and needs. Without that support, and without trust in the processes by which science and its applications are developed and regulated, fear of change and the blocking of the potentially huge benefits of science and technology will surely result. Mass political engagement is perhaps an ambition too far for some of us, desirable though it is, but we know we can make a practical difference through public dialogue on science-related issues. References Bodmer, W. (1985) Public Understanding of Science (London: Royal Society). Durodié, B. (2003) Limitations of public dialogue in science and the rise of new ‘experts’, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 6(4), pp. 82–92. Fiorino, D. (1990) Citizen participation and environmental risk: a survey of institutional mechanisms, Science, Technology and Human Values, 5(2), pp. 226–244. House of Lords (2000) Science and Society. London: Third Report of the Select Committee on Science and Technology, at ⟨http://www.parliament.the-stationery-office.co.uk/pa/ld199900/ldselect/ ldsctech/38/3801.htm>. Irwin, A. (1995) Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise and Sustainable Development (London: Routledge). 358 R. Jackson et al. Downloaded by [University of Bath] at 01:40 03 January 2014 Jasanoff, S. (1997) Civilization and madness: the great BSE scare of 1996, Public Understanding of Science, 6, pp. 221–232. Kerr, A., Cunningham-Burley S. & Amos, A. (1998) The new genetics and health: mobilizing lay expertise, Public Understanding of Science, 7, pp. 41–60. Michael, M. (1996) Constructing Identities; the Social, the Non-human, and Change (London: Sage). Wilsdon, J. & Willis, R. (2004) See-through Science: Why Public Engagement Needs to Move Upstream (London: Demos). Wynne, B. (1989) Sheep farming after Chernobyl: a case study in communicating scientific information, Environment, 31(2), pp. 10–15, 33–40. Wynne, B. (1992) Misunderstood misunderstanding; social identities and public uptake of science, Public Understanding of Science, 1, pp. 281–304 Wynne, B. (1993) Public uptake of science: a case for institutional reflexivity, Public Understanding of Science, 2(4), pp. 321–337.