Canton Trade System & Opium War: Origins & Failure

advertisement

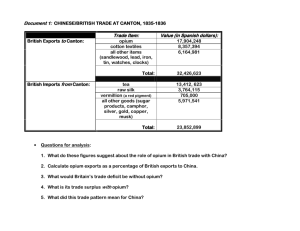

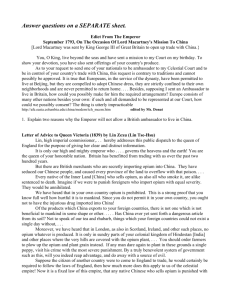

EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough The Canton Trade System and its Failure Introduction On the first of July 1997, Hong Kong was handed back to Chinese Authorities, ending more than 150 years of British control. Tung Chee-hwa, China’s first Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, declared: "This is a momentous and historic day ... Hong Kong and China are whole again." (BBC News, 2008). The ceding of Hong Kong to the British in 1843, after China’s defeat in the Opium War of 1839-42, has long been rued by the Chinese. This essay traces the origins of the first Opium War by examining the trading system that operated between Britain and China, known as the Canton System. It discusses the development of the Canton System and factors that caused frustration for traders, leading to its abuse with illegal trade. It argues that many problems associated with the Canton System were due to the late Qing government’s inward-looking disposition, closed-door policies and distrust of foreigners. China of this period was beset by internal problems which contributed to the breakdown of Chinese society and the Canton System. The Opium War might have been avoided with greater intercultural understanding and the development of productive diplomatic relationships. Evolution of the Canton System Europeans regarded China, with its tea, exotic silks, handcrafts and porcelain, as a highly desirable trading partner. By the late 1690s, European trading ships visited Chinese ports regularly. With the Portuguese outpost of Macau nearby, the Chinese port of Canton, known today as Guangzhou, became a target for traders because it offered security and access to someone who could communicate with the Chinese, even if via Portuguese. In Page 1 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough 1715 the Chinese government declared Canton the only port for foreign trade. English merchants were first on the scene, eventually joined by French, Dutch, Austrian, Danish and Swedish East India Companies, as well as `country' (private) ships from India and the Americas after 1784. (Van Dyke, 2005) A limited number of government-approved Chinese merchant-wholesalers, known as Hong merchants, were commissioned to act as brokers for, and supervisors of, foreign traders. Each ship was allocated to one of these Chinese firms. The Hong merchants formed a guild, called the Cohong in 1720. All orders and purchases had to be made through members of the Cohong, at prices negotiated by the Guild with the up-country suppliers. The Guild answered to the head maritime customs official, known as the Hoppo. The Cohong and the Hoppo were responsible for taxing the goods traded, both imports and exports. (Fairbank & Goldman, 2006) Merchants were required to pay fees to enter and leave Canton, levied according to the size of the ship. Foreign ships were required to anchor, unload and receive cargoes off the island of Whampoa, downstream of the city (see Figure 1). Here they also had to hand over all weapons and gunpowder into Chinese custody. The merchants were required to build their trading warehouses, known as factories, on a strip of land along the river front west of the city walls (see Figure 2). The factories also served as traders’ homes. From October to March the trading season ensued, while outside those months, merchants had to retreat to Macao or their homeland. (Gregory, 2003) When a foreign ship arrived, a linguist was appointed to assist with trading negotiations. The first translators used by the British were Cantonese-speaking Chinese residents of Macao who also spoke Portuguese. To communicate with officials, they also needed to be fluent in Mandarin. By the 1730s, a form of Pidgin English had replaced Portuguese. The British relied on these linguists, who had only a transactional vocabulary. They acted as mediators between the Hong merchants and the traders, negotiating and persuading them to reach a trading agreement. (Van Dyke, 2005) Page 2 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough Figure 1: Map of the delta of the Pearl River, with the Macau Peninsula, Whampoa and Lintin Islands marked. (from Hanes & Sanello, 2002, p.308) Page 3 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough From 1760, further restrictions were introduced. Foreign ships were not permitted to communicate with Chinese people or merchants without supervision and foreign traders were not to communicate with Chinese officials except through the Cohong. Women, including traders’ wives, were not allowed in the factories. A maximum of eight Chinese servants were allowed to be employed in any factory, regardless of size. Foreigners were not allowed to row boats on the river, nor were they allowed into the city. They could take recreation on the 8th, 18th and 28th days of the lunar cycle on Honan Island (see Figure 2) by visiting the Flower Gardens and the Joss-house, but only in groups of ten or fewer. If they entered other public places, their interpreter would be punished. As well, foreigners were not permitted to buy Chinese books or learn the language and the Chinese were also not allowed to own foreign books. (O’Brien, n.d.) Figure 2: Sketch map of Canton showing the location of the Foreign Factories (from Clowes, n.d.) Page 4 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough Frustrations with the system leading to breakdown As the system evolved, it became increasingly difficult for traders. Apart from the personal restrictions on traders, trading grew less efficient over time. As the number of ships increased the number of Hong Merchants and associated service providers did not, resulting in lengthy waiting periods. While in the early days the Hoppo would deal directly with traders, as the system evolved, the Cohong became the direct contacts. With this, traders were denied contact with Chinese Officials and the Officials became less familiar with the particular issues confronting trade in Canton. (Van Dyke, 2005) Traders lost all channels of communication to seek change or review of the System. Traders were required to engage a variety of service providers and general dissatisfaction with them was evident. For example, a Chinese Pilot was required to allow a merchantman enter the Pearl River and yet they were unskilled in the role, while shipping charts provided ample direction. (Davies, 1836) Linguists were another source of angst. Every trader was able to choose their assigned Chinese linguist, but the choice was extremely limited, with only five or fewer operating in any year. Linguists were not supposed to translate anything that might offend, and often feigned ignorance by way of excuse when communications became vexed. Their services, while necessary, were not always accurate and many complaints were made by foreign merchants against their linguists. (Van Dyke, 2005) With a large amount of responsibility given to a relatively small number of firms, corruption grew at every level, from the Hoppo to the lowest Customs Officers. Traders also sought to evade what they saw as excessive port changes. (Davies, 1836) A smuggling depot at Lintin island (see Figure 1) commenced operation in the early 1820s and illicit trade, largely opium, was fuelled by an 1825 policy that exempted ships bringing rice and no other goods from all port charges. As John Davies, the Chief Superintendent in China reported: Page 5 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough “Vessels accordingly now station themselves at Lintin, laden with rice, which they sell in sufficient quantities to other vessels, newly arrived, to exempt them from port charges; while the real cargoes are either left at Lintin to be smuggled in, or put onboard other ships which fill themselves up entirely on freight for Whampoa..” (Davies, 1836 p.429) The British also desired access to a northern port, where the colder climate would make British woollen products attractive. Inland freight charges made the importation of such products at Canton uneconomic. (Davies, 1836). It is testament to the profitability of the Canton Trade that merchants continued to labour under its restrictions. The next section summarises economics related to British trade at Canton. The British East India Company – Tea and Opium The East India Company was the sole British trading company at Canton, having been granted a monopoly on trade in Asia. It conformed to Chinese law, traded solely through the Cohong and acquired a reputation for honesty and fair dealing. (Gelber, 2004) The Company came to trade in three principal commodities – tea, silk and porcelain. Tea consumption began as a fashionable drink among British elite classes, quickly spread through society with the result that tea quickly became the prime British import from China, as can be seen from Table 1. In 1813, Customs import duty on tea provided roughly 10 percent of the British government's annual revenues. By the 1830s, Chinese tea import duties provided the entire profit of the East India Company. Tea became so important to Britain that the Company had to keep one year’s supply in stock to avoid shortages. (Greenberg, 1969) Page 6 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough Table 1 - Tea Imports to England From Davies (1836), p 448 Year British Tea imports (lb) 1734 632,474 1746 2,358,589 1758 4, 205, 394 1768 6,892,075 1785 10,856,578 1800 20,358,702 1833 31,829,619 China’s demand for British goods was small in comparison to Britain’s need for tea, and Britain was forced to pay for tea with silver, causing the British trade deficit to grow. The main item China imported was opium. India’s opium fields had been seized by the British in 1750, and opium began to be exchanged for tea. A trading triangle involving Britain, India, and China evolved and Britain’s trade deficit began to normalize and, eventually turn to surplus, because of its opium trade. (Gelber, 2004). A strong pain killer and effective treatment for tropical diarrhea, opium had been in use in China from the fourteenth century, brought in by Muslim and Portuguese traders. Gradually its medicinal uses were overtaken and it became a popular luxury item. By the 1600s, opium, as well as tobacco smoking, was embedded into the recreational culture of high-ranking Chinese officials. Prior to 1868, growing, trading, and recreational use of opium was legal in Britain. It was also legal in China until the first anti-opium edict of 1729 forbade its sale for smoking purposes, a measure largely ignored. In 1796 the ban was extended to prohibit importation. At this point, the East India Company stopped exporting opium directly to China and, instead, sold it, quite legally, to private merchants, who delivered it to China for illegal sale. (Feige and Miron, 2005) The Canton System began to disintegrate as bribes to turn a blind eye to smuggling became commonplace. Smuggling was a significant problem by the 1820s, with Chinese administrators, as well as many of the Page 7 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough Cohong involved in drug trafficking. Instead of enforcing imperial edicts, officials promoted and exploited opium trade, growing richer in the process. (Gelber, n.d.). Table 2, shows estimates of illegal opium imports into China. The true amount of opium that entered China in the early 1800’s will never be known as by this stage, opium was coming in from America and also being grown in China, although British shipments dominated. Table 2 Opium shipments to China 1830 – 39 (summarised from Zheng, 2005, p.93) Trading Season 1830/31 1831/32 1832/33 1833/34 1834/35 1835/36 1836/37 1837/38 1838/39 Total number of chests 19,956 16,550 21,985 20,486 21,885 30,202 34,276 34,373 40,200 A chest of opium contained between 130 and 140 pounds of product. This puts the illegal quantity smuggled into China for 1838/39 at between 2370 and 2553 tonnes, an enormous quantity. Figure 3 illustrates the scale of warehouse storage of opium balls in India. Page 8 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough Figure 3. An opium storehouse in India belonging to British merchants, c.1839. (from Guan, 1987, p26) While the British have been accused of ruining China by flooding the market with opium, had there been no demand, the trade could not have flourished. With the Chinese economy in recession and silver flowing out of the country to pay for opium, in 1839 the Emperor assigned Commissioner Lin Tseh-hsü, a Mandarin known to be incorruptible, the task of suppressing the opium trade. After seizing and destroying large quantities of British opium, Lin adopted measures which put British traders’ lives at risk by preventing food shipments to British ships and poisoning their water supplies. (Waley, 1958) The Opium War, beyond the scope of this essay, broke out in the same year. Many questions arise out of this narrative. Why did China adopt essentially a closed-door policy to the West? Why was there such a demand for opium and why was no effective action taken to prevent opium smuggling? To explore these questions, the political context of the times must be considered, together with an attempt to discuss the Chinese perspective on these issues. Page 9 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough Chinese society – beset by problems A result of the peaceful rule of the early Manchu Emperors was population growth, as shown in Table 3. Until the mid 1700s, population growth had been paralleled with economic growth. After that, food production could not keep up with the needs of the burgeoning population. All arable land was under cultivation and as the population increased, the amount of land per family farm decreased. The standard of living dropped generally and poverty fuelled internal migration to cities, unemployment and social unrest. (Fairbank & Goldman, 2006) Table 3 Population of China 1770 – 1840 Statistics from the Ministry of Revenue in Peking Source: Chesneaux, Bastid and Bergere, 1977, p 47 Year 1770 1780 1790 1800 1810 1820 1830 1840 Estimated Population 213,613,163 277,554,413 301,487,114 295,273,311 345,717,214 353,377,694 394,784,681 412,814,828 Corruption evident in the Canton System became endemic throughout society, with mandarins and district officials levying additional taxes, taking bribes and manipulating exchange rates between rice, silver and copper cash to their benefit. This worsened conditions for the poor and reduced imperial revenue. Secret societies became very active, attracting discontented peasants seeking outlets for their anger. These underworld gangs bribed and terrorized the population. Public services declined and infrastructure, such as dikes, canals and granaries, fell into disrepair. As well as peasant revolts, famine and natural disasters occurred more frequently. (Chesneaux, Bastid and Bergère, 1977) Page 10 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough As the quantity of opium smuggled into China increased, its price decreased, making it more accessible to poorer classes in society. Figure 4 illustrates the plummeting prices of Opium after the early 1820s. Figure 4. Graph showing the price of opium exports in India. (from Feige and Miron, 2005, p9) China’s legal archives indicate that lip service was paid to Imperial Edicts, with poor migrants from other provinces most likely to be prosecuted for opium offences, while, in the main, opium smokers and dealers eluded prosecution because of their connectedness to police, who turned a blind eye to their activities, or through intimidation from members of secret societies associated with the black market. The Chinese Government was clearly ineffectual in its internal war against opium. (Macauley, 2009) The spread of opium can be understood in the social context of widespread administrative corruption and active criminal networks. Opium smoking provided an escape from the harsh realities of daily life for many Chinese in such troubled times and opium became more accessible as the market was flooded with the product. Page 11 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough A clash of cultures perpetuated by a closed-door policy During her long history, China had always been at the centre, the Middle Kingdom, a civilized world surrounded by inferior cultures. Ruled by the Son of Heaven and bound by Confucian ethics, Chinese society was seen to approximate the natural order of the cosmos. The Five Relationships, subject to ruler, wife to husband, son to father, younger to elder brother and friend to friend, underpinned society. Confucian society was hierarchical, with scholar-officials most superior, then farmers, artisans and, most lowly, merchants. (Fairbank, Reischauer and Craig, 1965) Countries that traded with China were considered tributaries, bearers of gifts; a small price to pay for contact with the Middle Kingdom. The Chinese tribute system involved symbolic rituals, including the kowtow, which were regarded as ‘good manners.’ The Chinese put the modern West into this category, expecting them to be humble and submissive to the Emperor, who was benevolent towards those from afar. (Pritchard, 1943) In 1793, Lord McCartney conducted Britain’s first diplomatic mission to China. His agenda was to negotiate a treaty of commerce, establish a resident diplomat, extend British trade to other ports, improve the organization of the Canton trade and gain place near Canton where British merchants might be able to stay all year, under protection of British justice. (Hibbert, 1970) None of the objectives were achieved, although he was granted an audience with the Emperor. Lord Amherst, who visited in 1816 was also unsuccessful. Neither ambassador was prepared to cast Britain as a tributary nation; this may have represented a significant breach in protocol to the Chinese. (Pritchard, 1943) With the dissolution of the East India Company’s monopoly in 1834, Britain appointed Lord Napier as Chief a Superintendent of Trade at Canton. With no experience in diplomacy, and no previous contact with Asia, his clumsy and culturally insensitive attempts at engaging with the Chinese inflamed an already troubled situation. (Hibbert, 1970) Chinese and Western cultures clearly clashed in these diplomatic debacles. Page 12 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough The Confucian view of trade as a lowly activity may have influenced the choice of Canton as international trading port. Situated far in the south and distant the capital at Peking, Canton’s location was an expression of the lack of importance foreign trade in the eyes of the Chinese, as well as its preference to keep foreigners at a distance. The extraordinary restrictions on the Canton merchants suggest that the Chinese were deeply suspicious of foreigners. Fairbank (1969) interprets this xenophobia as the response of an elite class that had been trained to treat those who acted like Chinese as Chinese, but those who didn’t as barbarians. By the early 1700s, China was largely self sufficient. The size and diversity of China’s regions ensured a variety of produce and with navigable waterways a complex network of domestic markets had developed. It has been estimated that China’s domestic trade market was bigger than the total European trade market of the time. (Fairbank and Goldman, 2006) The closed-door approach may have been a result of the Chinese believing that they had little to gain and much to lose by opening its door to Western traders. It is contended that China’s closed-door policy was a significant reason why the clash of cultures continued, and the policy had the unintended consequence of preventing the Chinese from gaining knowledge about the West. By delegating interaction with traders to the Cohong, Chinese officials lost the opportunity learn about the West. With little contact, their views were uninformed. Commissioner Lin’s journal, for example, revealed a widespread Chinese belief that foreigners would die of constipation if deprived of rhubarb as well as bizarre ideas about ingredients used to prepare opium. (Waley, 1958) Chinese literature of the early nineteenth century indicated a lack of geographical understanding about the world beyond China, confusion about western nations. (Fairbank et al, 1965) Page 13 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough The ban on language learning prevented the development of mutual understanding. While traders were able to get by with limited language resources, diplomacy required much greater knowledge of subtle meanings in language as well cultural knowledge. China’s closed-door policies worked against the development of these understandings and prevented productive diplomacy. Conclusion China’s self sufficiency made it a reluctant a reluctant trade partner with the West, and the highly restrictive Canton system was devised to keep foreigners under control. The system worked well for China as she profited from trade in tea, silk and porcelain, while maintaining minimal contact with the West. The legal opium trade was part of the Canton System until it was outlawed in 1796. Internal decline was driven by a burgeoning population and an economy that was unable to keep pace. Massive poverty and internal corruption fuelled rebellion and crime. A network of secret societies took over the distribution of opium after it was banned and illegal opium imports increased dramatically. Frustrated with the Canton system, British traders took part in illegal trade with abandon, as it was extremely profitable and poorly policed. Opium became cheaper and addiction at all levels of society occurred. The Chinese were unable to control illegal opium use in their society. Real difficulties in communication, exacerbated by the Qing’s closed-door policy and edicts that forbade language learning prevented effective diplomacy and the cultures of China and Britain continued to clash through lack of mutual understanding. These policies worked against their makers, as the Chinese remained largely ignorant of Western capabilities. One has to wonder whether the Opium War would have occurred if China had opened its door to the West. Page 14 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough References BBC News (2008) On this day: 1950 – 2005: 1 July 1997. Retrieved 10 May, 2010, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/july/1/newsid_2656000/2656973.st Chesneaux, J., Bastid, M. and Bergere, M.C. (1977) China from the Opium Wars to the 1911 Revolution. Sussex UK: The Harvester Press Limited. Clowes, W. L. (no date) William Loney RN – Background in W. L. Clowes on the First Anglo-Chinese War (“Opium war”) of 1838 - 1842 Retrieved 4 May, 2010,from http://www.pdavis.nl/China.htm Davies, J. F. (1836) The Chinese: A General Description of the Empire of China and its Inhabitants, Volume II. London, UK: Charles Knight & Co. Fairbank, J. K. (1969) Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast. The opening of the treaty ports 1842-1854. Stanford, Califorina, USA: Stanford University Press. Fairbank, J. K. and Goldman, M. (2006) China a New History, 2nd Enlarged Edition Massachusetts, USA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Fairbank, J. K., Reischauer, E. O. and Craig, A. M. (1965) East Asia. The Modern Transformation Boston, USA: Houghton Mifflin Company Feige, C. and Miron, J. A. (2005) The Opium Wars, Opium Legalization, and Opium Consumption in China. NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research) Working Paper No. 11355. Retrieved 12 June, 2010, from http://www.economics.harvard.edu/files/faculty/91_opiumwars_ael.pdf Page 15 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough Gelber, H. G. (2004) Opium, Soldiers and Evangelicals. Britain’s 1840-42 War with China and its Aftermath. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Gelber, H. G. (no date) China as "Victim"? The Opium War That Wasn't. CES Working Paper 136. Centre for European Studies Harvard University Retrieved 23 May, 2010, from http://www.ces.fas.harvard.edu/publications/docs/pdfs/Gelber136.pdf Greenberg, M. (1969) British Trade and the Opening of China, 1800-1842. London, UK: Cambridge University Press Gregory, J. S. (2003) The West and China since 1500, New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan. Guan, S. (1987) Chartism and the First Opium War. In History Workshop Journal 24(1):17-31 Oxford University Press, retrieved from http://hwj.oxfordjournals.org Hibbert, C. (1970) The Dragon Wakes: China and the West, 1793 – 1911. New York, USA: Harper and Row Publishers. Macauley, M. (2009) Small Time Crooks: Opium, Migrants and the War on Drugs in Imperial China 1819-1860. In Late Imperial China 30(1): 1-47 Obrien, J. V (no date) The Canton System of Trade. Retrieved 16 May , 2010, from http://web.jjay.cuny.edu/~jobrien/reference/ob30.html Pritchard, E. H. (1943) The Kowtow in the Macartney Embassy to China in 1793. In The Far Eastern Quarterly Review. 2 (2):163-203 Van Dyke, P. A. (2005) The Canton Trade: Life and Enterprise on the China Coast, 1700-1845. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. Page 16 of 17 EDAS8003A Assignment 2 Kay McCullough Waley, A. (1958) The Opium War through Chinese Eyes. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. Zheng, Yangwen (2005) The Social Life of Opium in China. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Page 17 of 17