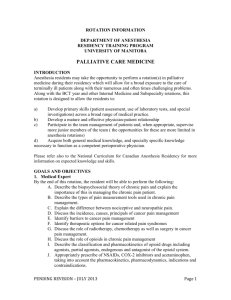

nursing home palliative care toolkit

advertisement