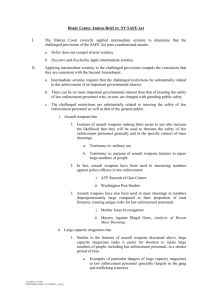

Public Mass Shootings in the United States: Selected Implications

advertisement