______ GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS History of the

advertisement

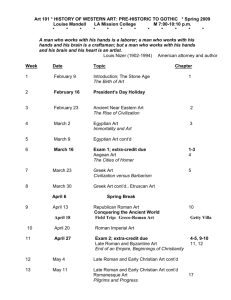

GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS History of the Collection The University of Missouri-Columbia owns about one hundred plaster casts of sculpture, mainly Greek or Roman, but eleven represent later periods. In addition, scale models of parts of three buildings are examples of the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders. Four of the casts were the gift of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in 1973, but the bulk of the collection was personally selected for the University in 1895 and 1902 by John Pickard (1858-1937), Professor of Classical Archaeology and founder, in 1892, of the Department of Art History and Archaeology at the University of Missouri. The records of the 1895 purchase show that the first fifty casts and the architectural models were acquired from casting studios in Germany, France, and England. Apparently no correspondence exists concerning the second acquisition in 1902, but the local newspaper reported that thirty or forty casts were acquired. Until 1940 the collection was displayed in a large gallery on the third floor of Academic Hall, the campus administration building, now called Jesse Hall, but, for a twenty-year period from 1940 to 1960, the casts were hidden from view, pushed aside to provide space for art classes. In 1960, the Art Department moved, and the Department of Art History and Archaeology was re-established. (In 1935 it had been split between the departments of Art and Classics.) The casts were brought back out, cleaned, and painted. In 1975 the collection was transferred to Pickard Hall where it is now housed, most of it in a gallery on the first floor, but some in the lecture hall, hallways, offices, and museum storage. Pickard Hall, the old Chemistry Building, was renovated in 197576 as the home of the Museum of Art and Archaeology and the Department of Art History and Archaeology. A tradition arose that the casts were exhibited at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis in 1904. The catalogue of the exposition makes no mention of casts of Greek and Roman sculpture, however, and a search through The Columbia Daily Tribune from August 29, 1903 to December 31, 1904 revealed no mention of an exodus of casts from the museum in Academic Hall to St. Louis, nor of their return. The university's exhibit at the exposition is mentioned, however, and Dr. Pickard is described as having secured increased space for it. Although plaster casts of sculpture are not included, a model in plaster of the university's grounds and buildings is listed as part of the university's exhibit. Perhaps this and Dr. Pickard's involvement in the exposition gave rise to the local tradition that the plaster casts of Greek and Roman sculpture also went to the Fair. Casts were included in the exposition, but these were acquired especially for it and were given to Southeast Missouri State Normal School (now Southeast Missouri State University) by Mr. Louis Houck, who acquired them at the exposition and presented them in 1904. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Funerary Monument (Cippus) Rome, Italy Roman, 2nd c. Marble Lent by the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York (L709) The inscription reads: D(is) M(anibus) Catiae Helpidi Q(uintus) Catius Felix To the shades of the departed, for Catia Helpis Quintus Catius Felix (gave this) The monument was found in the late 19th century with several others near an ancient tomb located about three-quarters of a mile from the Via Appia, the principal ancient road that led south from Rome. The inscribed monuments near the tomb identify it as belonging to the family of the Catii. The cippus has a jug and a libation bowl, or patera, carved in relief on the sides, common motifs on such monuments. On the front face, two incised lines guided the carving of the second line of the inscription. Part of the surface of this face appears to have been recut in ancient times. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Cast Collection Archaic Period Kouros from Tenea, ca. 575-550 B.C., Munich, Glyptothek. Athena, Temple of Aphaia, Aegina, West Pediment, ca. 490 B.C., Munich, Glyptothek. Fifth Century B.C. Harmodios the Tyrannicide, Roman copy of a bronze from the group by Kritios and Nesiotes, ca. 477-476 B.C., Naples, National Archaeological Museum. Charioteer, bronze original, ca. 475-470 B.C., Delphi, Museum. Diskobolos or Discus Thrower, Roman copy of a bronze original by Myron, ca. 460-450 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museums. Apollo, Temple of Zeus at Olympia, West Pediment, ca. 465-457 B.C., Olympia, Museum. Head of Lapith Youth, Temple of Zeus at Olympia, West Pediment, ca. 465-457 B.C., Olympia, Museum. Head of Lapith Woman, Temple of Zeus at Olympia, West Pediment, ca. 465-457 B.C., Olympia, Museum. Head of Theseus, Temple of Zeus at Olympia, West Pediment, ca. 465-457 B.C., Olympia, Museum. Head of Hippodameia, bride of the Lapith king Peirithoos, Temple of Zeus at Olympia, West Pediment, ca. 465-457 B.C., Olympia, Museum. Herakles and Atlas, Temple of Zeus at Olympia, Metope, ca. 465-457 B.C., Olympia, Museum. Ludovisi Throne, three-sided relief, ca. 460 B.C., Rome, National Museum. Athena Lemnia (?), Roman copy of a bronze original by Phidias, ca. 450-440 B.C., head in Bologna, Museo Civico and body in Dresden, Albertinum. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Two Goddesses, The Parthenon, East Pediment, ca. 437-432 B.C., London, British Museum. Centaur and Lapith, The Parthenon, Metope, ca. 447-443 B.C., London, British Museum. Panathenaic Procession; Rider, The Parthenon, West Frieze, ca. 442-438 B.C., Athens. Panathenaic Procession; Marshal, The Parthenon, East Frieze, ca. 442-438 B.C., original missing. Head of the Diadoumenos, or Fillet Binder, Roman copy of bronze original by Polykleitos, ca. 440-430 B.C., Naples, National Museum. Doryphoros, or Spear Bearer, Roman copy of a bronze original by Polykleitos, ca. 450440 B.C., Naples, National Museum. Nike, by Paionios, ca. 425-420 B.C., Olympia, Museum. Battle of Greeks and Amazons, relief from the frieze of the Temple of Apollo at Phigaleia (Bassai), late 5th c. B.C., London, British Museum. Athena Velletri, Roman copy of a Greek work, perhaps by Kresilas, ca. 420 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum. Karyatid, the Erechtheion, Athens, ca. 421-406 B.C., London, British Museum. Nike, Temple of Athena Nike, ca. 410-400 B.C., Athens, Acropolis Museum. Athlete, Roman copy of a Greek original, ca. 450-440 B.C. Munich, Glyptothek Fourth Century B.C. Battle of Greeks and Amazons, the Mausoleion at Halikarnassos, ca. 360-340 B.C., London, British Museum. Hermes and Dionysos, by Praxiteles, ca. 350-330 B.C., Olympia, Museum. Torso of Satyr, attributed to Praxiteles, ca. 370-355 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum. Artemis from Gabii, Roman copy of a statue attributed to Praxiteles, ca. 360-330 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Head of the Demeter of Knidos, ca. 350 B.C., London, British Museum. Head of Euripides, Roman copy of a Greek original, ca. 350-325 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museums. Woman from Herculaneum, Roman copy of a Greek original, ca. 340-330 B.C., Dresden, Albertinum. Head, Temple of Athena Alea, Tegea, Pediment, perhaps by Skopas, ca. 350 B.C., Athens, National Museum. Apoxyomenos, or Youth Scraping Himself, Roman copy of a bronze original by Lysippos, ca. 340-325 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museums. Alexander: the Azara Bust, Roman copy of an original perhaps Lysippos, ca. 330-323 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum. Dancing Woman, Roman copy of a flute girl by Lysippos, ca. 320 B.C., Berlin, Staatliche Museum. Sophokles, Roman copy of a Greek original, ca. 340-330 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museums. Hellenistic Period Nike of Samothrace, ca. 200 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum. Medici Aphrodite (Venus de Medici), type of Knidian Aphrodite, early 3rd c. B.C., Florence, Uffizi Gallery. Apollo Belevdere, Roman copy of a Greek original, ca. 200-150 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museums. Zeus Battling the Giants, from the frieze of the Altar of Zeus and Athena, Pergamon, ca. 180 B.C., Berlin Museum. Borghese Warrior, signed by Agasias, ca. 100 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum. Aphrodite (Venus Genetrix), Roman copy of a Greek original by Arkesilaos, ca. 50 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum. Aphrodite of Melos (Venus de Milo), ca. 150-100 B.C., Paris, Louvre Museum. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Homer, Roman copy of Late Hellenistic work, ca. 150 B.C., Boston, Museum of Fine Arts. Laokoon and his Sons, by Hagesandros, Polydorus and Athanodoros, late 1st c. B.C.early 1st c. A.D., Rome, Vatican Museums. Roman Period Head of Roman Matron, ca. 200 A.D., Naples, National Museum. Ludovisi Hera, Roman work in the Greek manner of 4th c. B.C., Rome, National Museum. ________ MAA 5/96 ENTRANCE HALLWAY (FIRST FLOOR) Cast Collection Panathenaic Procession; Ritual Handing over of the Peplos, The Parthenon, East Frieze, 442-438 B.C., London, British Museum. Tympanum, Chartres Cathedral, West Facade, ca. 1145-1155, France. Jamb Figures (King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba), Collegiate Church, Notre Dame, ca. 1140-1150, Corbeil, France. Bronze Flagpole Base, 1501-1505, Alessandro Leopardi, Venetian, - ca. 1522, Piazza San Marco, Venice. Ceres, 1921, Sherry Fry, American, 1876-1966, plaster model for bronze figure on the Capitol dome, Jefferson City. CORRIDOR (FIRST FLOOR) Cast Collection Bust of Perikles, Roman copy, original perhaps by Kresilas, ca. 440-425 B.C., London, British Museum. Head of a Young Girl, grave relief at Eretria, ca. 360 B.C., Berlin. Dionysos, (Priapos?), bronze bust ca. A.D. 50, Roman copy of early 5th c. Greek original, Naples, National Archaeological Museum. Portrait of Sophokles, Roman copy of a Greek original, ca. 340-330 B.C., Rome, Vatican Museums. Head of Hygeia, 4th c. B.C., Rome, National Museum. Boy Removing a Thorn from his Foot (Spinario), Roman copy of a Hellenistic bronze original, late 3rd early 2nd c. B.C., Rome, Capitoline Museum. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS A History of Greek Sculpture Based on the Cast Collection The following account incorporates excerpts from William R. Biers, The Archaeology of Greece, An Introduction, 2nd edition (Cornell University Press 1996), by kind permission of the author. Problems of Identification and Interpretation of Greek Sculpture The Romans were great collectors, and works of what was for them already ancient Greek art were especially prized. Statues were carried off by the shipload from Greek lands both as war loot and as "collectibles." The source was soon exhausted, however, so the practice of making copies of works of famous artists of the past became a thriving business. With the loss of the original statues, we must depend mainly on Roman copies for an idea of the style of the famous artists of Greece. Unfortunately, there are serious drawbacks to our enforced reliance on copies made for the Roman market. Copies of Greek originals were made in many ways by artists of widely varying abilities. A statue could be copied more or less freehand or by means of a "pointing machine" that gave almost exact reproductions. Further problems arise in the ease with which a given type--for instance, a young athlete--could be changed into another type, such as Hermes, by the simple addition of an attribute by the copyist. Depending as we do on ancient authors' relatively vague references to particular works, we are often reduced to trying to pick out a likely reproduction of a famous statue from among a host of copies of varying quality. Further, once it is thought that a known work of a famous artist can be identified, one can never be certain how faithful the copy is to the original, or, when faced with varying treatments of such details as hair, which example is likely to have belonged to the original statue. These problems make the definite identification of the works of a particular sculptor and analysis of his style tricky at best, though this difficulty has not deterred the publication of numerous learned studies of individual artists. The knowledge that can be gained from meager evidence is incredible, but it is well to remember the problems involved. (Biers, p. 215) The cast collection at the University of Missouri contains casts of original Greek works and of Roman copies of Greek works. The kouros from Tenea, the Athena from Aegina, sculptures from Olympia and from the Parthenon, for example, are casts of original Greek works in marble. The charioteer from Delphi is a cast of a bronze original. The Diskobolos, the Doryphoros, and the Apoxyomenos, on the other hand, are casts of Roman marble copies of Greek works originally made in bronze. The inclusion of a support for the figure is a clue to the original material of the Greek work. Bronze sculptures stand without support, whereas copies in heavy marble cannot stand alone. The collection contains few examples of casts of original Roman works. The head of a matron, dating to ca. A.D. 200, is an example of a cast of a Roman work in marble. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Archaic Period, Introduction At the very end of the seventh century large-scale standing marble statues appeared as dedications in sanctuaries and as funeral monuments. In these works one can clearly see stylistic changes as sculptors worked out the realistic representation of the human body standing at rest. These figures are given conventional names: Kouroi for the nude males (singular, kouros) and korai (singular, kore) for the draped females. (Biers, p. 165) These sculptural forms are generally believed to have been derived from eastern prototypes, the kouros from Egyptian sources and the kore from elsewhere in the Near East. Although the extent and even the existence of the debt of early Greek sculptors to Egypt is debated, it is hard to deny it completely when one looks at a contemporary Egyptian standing male. The basic form, a stiff, upright figure with one extended leg and fixed frontal glare, remains the same throughout the century while the details of musculature and the rendition of the human body become increasingly realistic. (Biers, p. 166) A parallel development [to the kouroi] can be seen in the korai, the standing female figures...[but] since Greek society and artistic convention did not accept a nude female figure in this period, the korai are shown fully draped, the contrasting patterns and fabrics of their garments providing a rich field for the sculptors to mine. The earliest garment, the peplos, was a heavy one-piece tunic, generally of wool, which was frequently worn with an overfold and a shawl in the seventh century. Considered a typically Dorian or mainland dress, it hung from neck to feet and was fastened at the shoulder by a pin or fibula. Often a lighter garment of linen, called the chiton, was worn beneath it. (Biers, pp. 168-69) Then, as now, fashions underwent periodic changes. During the sixth century the peplos was discarded and a sleeved chiton was worn alone or with a mantle. The mantle, or himation, became the standard dress of the korai, draped obliquely from the right shoulder to below the left armpit. The folds and decoration of this garment and its contrast with the lighter chiton beneath encouraged decorative renderings, and the korai of the latter part of the century reach great heights of elaborate ornamentation. (Biers, p. 169) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Kouros from Tenea, ca. 575-550 B.C. This figure represents the kouros as it had evolved by the second quarter of the sixth century B.C. (The earliest stage is represented in the U.S.A. by a figure in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.) Its stance looks Egyptian, but there are important differences, the most obvious being that the figure is nude. This is unknown in formal Egyptian sculpture. The Tenea kouros still retains a block-like appearance, but the arms are separated from the body from below the armpit to above the wrist, and there is no back support as in Egyptian figures. Furthermore, the weight of the body is distributed evenly on both legs, unlike the Egyptian figures where the weight rests on the back leg. That the Tenea kouros belongs to a more developed stage than the earliest of the series is shown by certain details of the body which are modelled rather than being carved as linear patterns. Athena, Temple of Aphaia, Aegina, West Pediment, ca. 490 B.C The Athena from the West pediment displays features typical of Archaic korai. She is shown in frontal stance, wearing the himation and chiton, which retain the decorative patterned effect of the Archaic period. The symmetrical folds at the edges of her garments are typical of the late Archaic period. Her mouth is carved in the so-called Archaic smile. As a warrior goddess, she is armed, carrying a shield and wearing a helmet. On her breast and falling down her back is her aegis, the goatskin mantle given her by her father Zeus. Holes on the breast were for attachment of a Gorgon's head, and holes along the edges once held bronze snakes' heads. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Fifth Century B.C., Introduction The art of the first half of the fifth century is somewhat less uniform stylistically than that of the second half and has been interpreted less uniformly as well. For some it is a transitional period in which lingering Archaic forms exist beside more advanced Classical renderings. For others it is an experimental period or an early stage of the High Classical Style of the second half of the century. The period has all these characteristics. For convenience the term "Severe style" has been applied to the art of this period, encompassing the meanings of both transitional and Early Classical. The style is characterized by (1) a simplification of forms, (2) a return to the plain Dorian garments with a resulting simplification of treatment of drapery, and (3) new subjects often shown in motion or expressing emotion, with varying degrees of success. Often the moment just before or after an event or a moment of rest within a complex movement will be shown rather than the action itself. These last two characteristics are typical of Classical art in general, but they were new in the first half of the century. (Biers, pp. 195-96) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Temple of Zeus, Olympia "the most famous and at the same time the most important of the religious buildings of the first half of the fifth century..." (Biers, p. 196) Apollo, Heads of Lapith Youth and Woman, Head of Hippodameia, Head of Theseus, sculpture from the west pediment, ca. 465-457 B.C. The sculptures...sum up the nature of the Severe style of the first half of the 5th century...The west pediment contains a scene of action...A large central figure dominates, this time Apollo. The subject is the battle between the human Lapiths and the bestial centaurs at a wedding feast of the Lapith king. From the great central figure of Apollo, one of the most imposing figures to come down to us, who stretches out his hand to calm the uproar, great two- and three-figure groups of struggling bodies sink down toward each angle of the pediment. (Biers p. 218) The human figures, despite being engaged in a fierce struggle "appear calm; only the centaurs snarl and rage, contorting their features. Such idealization probably symbolizes here the superiority of civilized beings, in contrast to the uncivilized forces of nature; yet some of the humans, too, display natural emotions in occasional open mouths, pinched features, and lined foreheads." (Biers, p. 219) Herakles and Atlas, metope, Temple of Zeus, Olympia, ca. 465-457 B.C. The metopes of the temple of Zeus represent for the first time the twelve canonical labors of Herakles, six at each end of the building...A simple composition of three verticals makes up the scene of the labor of the Apples of the Hesperides. Atlas had returned with the apples in his hand, and Herakles, who earlier took the world from the giant's shoulders, considers how to reverse their positions. Athena is present, helping to support the burden with one hand, and Herakles has arranged a cushion to help ease the weight. These three dignified figures are shown in monumental simplicity. The Athena is especially handsome, wearing a plain peplos that falls in straight vertical folds broken slightly by the right leg to suggest the body beneath. As the daughter of Zeus, she is able to support the world with one hand. This is an oldfashioned composition, with its three vertical figures, but the unusual character of the scene and the monumentality of the figures go well beyond earlier conceptions. (Biers, pp. 220, 222) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Diskobolos, or Discus Thrower, by Myron, ca. 460-450 B.C. An extended pose is seen "in one of the most famous statues of antiquity, the Diskobolos (Discus Thrower) of Myron. The works of Myron, who worked in the middle years of the 5th century, display Severe as well as High Classical characteristics. His innovations in pose and composition were not paralleled until Hellenistic times. Unfortunately, his work is known only through Roman copies, and only one or two statues are securely attributed to him." (Biers, p. 216) The Diskobolos, originally in bronze...[has] an openness of form and a static anatomy in which the tension of the various parts of the body are hardly reflected. This figure...is meant to be viewed from only one angle; from the rear it appears impossibly balanced, and it is extremely flat. The human body cannot flatten itself to the extent shown here as numerous athletes can attest. The simplification of features, here idealized without individuality or emotion, is particularly striking. The head could easily be taken from the body and set up as a bust, so divorced is it from the action of the body below it. In general, the figure forms a beautiful, clear pattern--a legacy of earlier times but with idealized musculature and features. (Biers, p. 217) Charioteer, Delphi, ca. 475-470 B.C. One of few surviving fifth-century Greek bronze originals, this statue was found in the excavations at Delphi, where it had stood as part of a dedication of a chariot group by the tyrant Polyzalos of Gela in Sicily in commemoration of victory in a chariot race. The base with dedicatory inscription has survived, as well as parts of the horses, and the arm of one of the attendant figures. The statue was made by the lost-wax method and was cast in several sections: arms, lower legs with feet, skirt, upper body, head and neck, upper part of head above fillet, ends of fillet, and curls. The fully preserved eyes are inlaid with white paste; irises are brown and pupils in black onyx. The eyes are rimmed by bronze lashes. The charioteer wears a long chiton which falls in regular folds held by diagonal straps that are drawn tightly under the arms and then by the belt around the waist. The pose is quiet, perhaps representing the moment when the charioteer has pulled his horses to a stop. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Second Half of Fifth Century B.C., Introduction In the second half of the century, or more specifically in the period of Periklean supremacy (460-429), a very strong and potent style developed. In this High Classical style, which had its roots in much of the sculpture of the earlier part of the century, the human form was idealized. Individual traits were suppressed, as were extremes of youth and old age; almost the only subjects were perfect men and women in their prime. A certain homogeneity was achieved; it has been said that all High Classical statues look alike, with their straight noses, down-turned mouths, vacant stares, and simplified musculature. This powerful style has been seen as the creation of Perikles' circle, especially of his chief artist, Phidias... (Biers, p. 196) Doryphoros, by Polykleitos, ca. 450-440 B.C. Polykleitos was a Peloponnesian sculptor who was known for his idealized humans. The most famous of his works, the Doryphoros or Spear Bearer, known from a number of copies, was highly praised in antiquity and has exercised great influence ever since. The figure is shown striding forward, holding a spear, now missing, over his shoulder. The original, doubtless made of bronze, would have had no need for the supporting tree trunk that has necessarily been included in the marble copy. The closeknit musculature, with the major divisions of the body clearly marked, and the idealized head with close-cropped hair are typical, as is the stance. The man rests his weight on his right leg while the left is pulled back and to one side, with the foot resting lightly on its toes. This suggestion of shifted weight is reflected in the makeup of the whole, in which a rhythm of tension and relaxation is achieved. Thus the right arm hangs straight and free while the opposite left leg is bent without tension. The left arm and the right leg similarly oppose each other. The head is inclined slightly toward the engaged leg. The whole composition produces a freedom and sense of movement not achieved before. The stance is often described by the Italian word contrapposto (counterpoise) and is from this time on a constantly recurring pose in art. (Biers, pp. 222-23) The Doryphoros is said to embody "the canon of Polykleitos," the sculptor's ideal of human proportions, and attempts to explain this canon by observations and theories have been a favorite pursuit of scholars. The lack of any originals and the ambiguous nature of the literary evidence have made the problem fiendishly complicated. Most scholars feel that the canon rests on mathematical or geometrical relationships of proportions. Others, noting the lack of success in deriving any system from a study of various copies, have suggested that the sculptor wilfully deviated from an ideally proportioned body in order to give the figure the illusion of life; the parts of the human body, after all, bear no precise mathematical relationship to each other. (Biers, p. 224) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Sculptures from the Parthenon The sculptures of the Parthenon hold the same high place as representatives of their age as do the sculptures of the temple of Zeus at Olympia. The great building...not only had sculptures in all the metopes and both pediments but also had a sculptured frieze on the outside of the cella wall within the colonnade. This frieze, almost 160 meters long, ran all the way around the building at the top of the wall. Phidias was in overall charge of the Periklean program on the Acropolis and of course made the cult statue for the building. Although his hand cannot be detected among the surviving sculptures, the elaborate and carefully planned program of decoration needed a single author, and one is probably right in seeing the sculptor's influence throughout. (Biers, p. 225) Metope: Centaur and Lapith, ca. 447-443 B.C. Most of the Parthenon's metopes have been destroyed; those that have survived are mainly from a series depicting Lapiths and centaurs in battle. [The museum's metope] shows a successful composition and an advanced treatment of anatomy. The Lapith has seized the centaur with his left hand, and with feet braced and breath sucked in stretches his right arm back to deliver the final blow. The Lapith's cloak, draped from both arms, hangs behind him, forming a background originally painted blue, against which the body stood out. The cloak serves as a device to emphasize the thrusting bodies and provide unity and balance for the diverging movements. The audacity of the composition and the powerful treatment of the bodies make one easily overlook the fact that the centaur's tail merges with one of the folds of the cloak. (Biers, p. 226) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Sculptures from the Parthenon Frieze: Rider, Marshall, and Ritual Handing Over of the Peplos, ca. 442-438 B.C. Probably the most original and debated portion of the Parthenon's sculptural decoration is the frieze. Beginning at the west end, a procession moves along both the north and south sides of the building to the east front, where a ritual appears to be taking place. Most scholars agree that the procession on the frieze relates to the Panathenaic procession, the most important ceremony of Athens, in which a new peplos was solemnly carried up to the Acropolis in Periklean times to drape the old olivewood statue of Athena in a building on a site later occupied by the Erechtheion. Whether the procession that is shown on the Parthenon frieze represents a specific occasion or is intended to be a general, idealized representation of all such processions, the people taking part in it are unmistakably citizens of Athens. The representation of human activity, no matter how solemn and idealized, on a religious building instead of a mythological scene is unparalleled in Greek art up to this time, and must surely reflect the attitude of Perikles and his circle; no doubt it was seen as arrogance and sacrilege by many others. (Biers, p. 226) The problem of interpretation is most acute on the east frieze, where two figures, a larger and a smaller, handle what appears to be a large square of cloth. The cloth is usually taken to be Athena's peplos, but whether it is the new one brought by the procession or the old one and just what is happening to it are debatable....seated Olympian gods are shown flanking the central scene, as if waiting for the procession to arrive. The gods are evenly arranged on either side of the peplos scene, but with their backs turned to it. They appear to be talking to one another...Granted that the gods may be understood to be gathered somewhere removed from the principal scene, their large size and placement still seem peculiar; one expects something better in view of the masterful handling of the procession. The very placement of the Greek gods in the same scene with the people of Athens may have been considered enough of a departure from tradition, and conservatism, or perhaps political considerations, may have dictated the obvious attempt to separate god and mortal while still indicating a special relationship. (Biers, p. 227) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Sculptures from the Parthenon East Pediment, Two Goddesses, ca. 437-432 B.C. The pediments, the last of the sculptural decoration to be completed,...have unfortunately survived in extremely fragmentary condition...The subject [of the east pediment] is the birth of Athena, but without the central sculpture we cannot be certain how it was shown...Heaviness and opulence can be seen in the seated and reclining figures [the two figures in the cast collection]...the heavy forms are scarcely obscured by the elegant drapery, which is molded around them. The sculptor has finally learned to dig deeply into the marble, and the resulting heavy folds and play of shadow suggest volume and modelling. The folds are still consciously arranged for decorative effect and the garments retain their own character, though they have become more transparent. The pediment figures are worked fully in the round, with a wealth of detail that could never have been seen from the ground. The overall carving is incredibly high, in fitting with the overall conception of the building. (Biers, p. 234) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Fifth Century, 425-400 B.C. The last quarter of the century saw a loosening of the Phidian style in the direction of elaboration and sophistication of treatment of details, especially drapery. This change can be clearly seen in the sculptures of the Nike Parapet... (Biers, p. 196) Nike, Temple of Athena Nike, ca. 410-400 B.C. The representation of clinging transparent drapery, the so-called wet-drapery style, was current at the end of the fifth century, and its most famous examples are found in Athens, on a parapet that surrounded the little Ionic temple of Athena Nike erected on the Acropolis in the last decade of the century. The relief depicts Victories (Nikai) erecting trophies or bringing sacrificial animals to Athena, and their elaborate draperies appear to have been the artist's main interest. When the fabric is pressed close to the body, its transparency is emphasized by shallow ridges; elsewhere it is deeply drilled to produce billowing folds independent of the anatomy beneath it. The emphasis on beautiful decoration is a departure from the style of the Parthenon sculptures, which show neither highly transparent draperies nor elegance and mannered gracefulness. (Biers, p. 236) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Fourth Century B.C., Introduction In one way the sculpture of the fourth century was a logical extension of that of the fifth: stylistically, many of its characteristics were direct continuations of previous practice. A change is noted in the treatment of subjects, however: sculptors moved away from the uniformity of High Classical art to depict emotional states...The names of a number of fourth-century sculptors have come down to us from comments in the works of ancient authors and from inscribed statue bases. Three represent distinct styles: Praxiteles, Skopas, and Lysippos. (Biers, pp. 263, 264) Hermes and Dionysos, by Praxiteles, ca. 350-330 B.C. Praxiteles (the "sculptor of grace"), whose career is usually given as stretching from about 370 to about 330, was one of the most famous Greek sculptors... (Biers, p. 264) A statue of Hermes carrying the baby Dionysos was found in the Temple of Hera at Olympia by German excavators in A.D. 1877. The statue was immediately connected to Pausanias' statement that a marble statue of Hermes and Dionysos by Praxiteles was in the temple when he visited it. Subsequent technical studies, however, have thrown doubt on it as a work of the master, and most scholars no longer believe it to be an original. Several suggestions have been offered: that it is a copy of a fourth-century original made at a later date, or an original by another sculptor, or an original work by Praxiteles that was altered and reworked in Roman times. Whatever the answer, the statue is an outstanding work of sculpture that awakens in the viewer a strong subjective reaction that can easily cloud judgment of its intrinsic merits. Although the right arm, the left leg below the knee, and the right leg between knee and ankle are missing (the legs have been restored), the statue is well preserved, especially the head. The god is shown leaning on a tree trunk over which he has slung his cloak, holding the baby Dionysos in the crook of his left arm, which is supported by the tree trunk. His right arm is extended; he probably held a bunch of grapes, for which the baby wine god stretches out his chubby hand. [The museum's cast restores the right arm and the bunch of grapes.] The figure, with the flexed left leg and outthrust right hip, describes an Scurve, the so-called Praxitelean curve. Hermes' musculature is very softly treated: the various muscles and parts of the body flow into one another with few distinct divisions. A comparison with the sharply defined musculature of the Doryphoros reveals a strong contrast in treatment. The softness is apparent in the head, whose features appear to be almost veiled. The god stares out into space with a dreamy expression, not looking at the child. The hair which is worked in tufts, contrasts with the heavy brow, straight nose, and thick lips, but the contrast is not at all jarring. (Biers, p. 265) In the Hermes of Praxiteles the gods have shed their Olympian grandeur and become soft and languid human beings. This almost effeminate figure is clearly far different from the gods of earlier Greek art. (Biers, p. 265) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Head, Temple of Athena Alea, Tegea, perhaps by Skopas, ca. 350 B.C. A contemporary of Praxiteles was Skopas of Paros, whose style is marked by contorted poses and strong emotions. Apart from a few literary references that seem to indicate these elements of style among others in his repertoire, we are dependent on a rather thin thread of reasoning in assembling possible examples of his work...Skopas is known to have been the architect of the temple of Athena Alea at Tegea. In the course of excavations, fragments of the pedimental sculpture were found, including a few extremely battered heads that show traces of a sturdy individual style that seems to fit the artist. One head [the museum's cast] exhibits a sharply turned square shape and distinctive deep-set eyes...If we may judge from what little is known of Skopas' style, he seems to owe something to the Polykleitan tradition while also introducing active, twisted poses and representations of emotion. (Biers, pp. 267-68) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Apoxyomenos, by Lysippos, ca. 340-325 B.C. The third great sculptor of the fourth century was Lysippos, a native of Sicyon in the Peloponnesos. He seems to have been working before the middle of the century, but the greater part of his career falls within the second half of the century. Alexander, who was born in 355, was one of his subjects while he was still a child, and in later years he appointed the artist court sculptor. (Biers, p. 268) An extremely prolific sculptor, said to have produced 1,500 works, Lysippos belongs more to the coming Hellenistic period than to the Classical past. He was the first to introduce three-dimensionality to sculpture, with open forms that can be viewed from more than one vantage point. One of his greatest innovations was his departure from the Polykleitan canon of proportions. Unfortunately our knowledge of his works must depend on Roman copies that do not reproduce one of the qualities that made him famous--his treatment of surface and details. (Biers, pp. 268-69) One of Lysippos' most famous works was a bronze Apoxyomenos, or Young Man Scraping Himself, which was especially prized by the Roman emperor Tiberius. A marble copy of it exists in the Vatican. A comparison of this statue with the Doryphoros clearly shows the change in proportions. Lysippos' youth appears taller and thinner, with a smaller head and longer legs than we find in the solid and close-knit Doryphoros. The young man is an athlete in the act of scraping oil and dust from his right arm with a metal instrument called a strigil which is missing from the copy. His pose recalls the Polykleitan stance, but there is no alteration of tense and relaxed muscles in the body. The body is caught at the moment of overall action. The right arm is thrust out into space while the left crosses in front of the chest, thus partially obscuring it. This breaking of the frontal plane by the outthrust right arm is an important departure that foreshadows the more completely three-dimensional works of the Hellenistic period. Lysippos is quoted as saying that he portrayed men as they appeared to the eye, and the momentary quality of the Apoxyomenos shows this drive for naturalism. (Biers, p. 269) Alexander: the Azara Bust, perhaps by Lysippos, ca. 330-323 B.C. Portraits of Alexander exist in such profusion that it is difficult to identify one that might be attributed to Lysippos. Features said to be typical of Lysippos' portraits, a turning of the head and distinctive hair, are to be seen in a bust inscribed with the king's name. It dates from Roman imperial times and is poorly preserved, but it may have been modeled on one of Lysippos' works. The reflection of personality in portrait was more fully developed in the Hellenistic period than in earlier years, but Lysippos may well have been an innovator in this area as well. (Biers, p. 269) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Hellenistic Period, Introduction Sculpture in the Hellenistic age presents a wealth of examples and an abundance of problems. The new cities demanded sculpture in great quantities and of many kinds, giving unprecedented opportunities to working artists. Many of their works have been preserved, and more are known from Roman copies...One characteristic that runs through the works of the period, continuing from the fourth century, is the realistic reproduction of nature. The interest in realism can be seen in uncompromising fidelity to natural models in dramatic, emotional works. (Biers, p. 295) Zeus Battling the Giants, Altar of Zeus and Athena, Pergamon, ca. 180 B.C. The greatest monument of the Hellenistic age is the Pergamon Altar erected about 180 as a memorial to the victories of Attalos I (241-197) and dedicated to Zeus and Athena. The high platform to hold the altar was erected on a terrace of the acropolis. A giant central staircase, 20 meters wide, was framed on three sides by a podium bearing an Ionic colonnade. The podium was decorated with a great sculptured frieze some 2.3 meters high depicting the battle of gods and giants. The theme, an old one that had appeared in the sixth century on the frieze of the Siphnian Treasury of Delphi, was appropriate for a war memorial and also suggested a parallel between the triumph of the gods and the victories of the Greeks--both the defeat of the Persians by the Athenians and the defeat of the Gauls by the Pergamenes, who viewed themselves as the champions of Hellenism. Fully seventy-five gods and their adversaries are shown in the frieze...The giants are shown mainly in human form, but often winged or with snakes for legs. (Biers, p. 299) [The slab in the museum's cast collection shows Zeus fighting with three giants, one collapsing with a thunderbolt through his thigh. On the altar Athena is grouped with him, both figures in strong diagonal poses. Their movements]...clearly were inspired by the pediment sculpture of the Parthenon, and it is thought that the Athena probably resembled the lost Athena from the east pediment. Similar visual references to earlier works are to be found throughout the frieze. (Biers, p. 299) As can be seen...the old rules no longer apply in this new world. The large figures use up all available space and on the side adjacent to the steps actually writhe out of the frieze, putting an arm or a leg on the staircase. All is action, with a multitude of details and dramatic incidents. The deep-set eyes and agonized expressions on the giants' faces show depths of emotion not seen before, and perhaps just bordering on exaggeration. The massive anatomy of the Zeus is typical of this style; muscles and veins stand out as if pumped up with air. (Biers, p. 299) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Nike of Samothrace, ca. 200 B.C. The Nike or Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre is one of the most famous statues of antiquity. Originally part of a dramatic composition that included a reflecting pool and the prow of a ship, on which Victory was alighting, she was erected to celebrate a naval victory; exactly which one is debated. Excavation evidence has provided a date around 200 for the erection of the base, and it is generally agreed that the work was made by a Rhodian sculptor. The large figure (2.45 meters high) is shown sweeping through the air with her drapery blown back against her body, imparting a strong sense of motion. The treatment of the folds is reminiscent of some of the figures on the Pergamene frieze, on which we know Rhodian sculptors were engaged. This mighty Victory indicates that the Hellenistic age could render traditional subjects in original ways. (Biers, p. 307) Aphrodite of Melos (Venus de Milo), ca. 150-100 B.C. The Aphrodite of Melos was found on that island in A.D. 1820 and is accepted today as the personification of feminine beauty, at least for the ancient world. The larger-than-life-sized figure (2.04 meters in height) probably leaned on a pillar originally, a presumption that would account for the almost Praxitelean S-curve of the heavy torso. The drapery wound around the hips appears unstable, and there is a marked discrepancy between the fleshy, matronly body and the head, which is coldly classical. These features have been cleverly joined together, however, and the curved leaning pose imparts a freshness to the figure that perhaps accounts for its fame. But it must be recognized that the figure incorporates a number of features derived from various periods. (Biers, p. 307) Homer, ca. 150 B.C. The realism of the late Hellenistic period is well expressed by this powerful portrait of the poet Homer. This Roman copy is one of more than twenty that have survived from antiquity, all based on a Greek original of ca. 150 B.C. The Greek portrait, an imaginary one of the poet who may have lived in the 8th century B.C., is a masterpiece of carving that expresses the unknown sculptor's concept of the poet. Often called the blind Homer, the portrait reveals an individual whose mind is turned inward to his own visionary world. The deep carving of the features of the face produces a wonderful play of shadows that enhances the sculptor's concept. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Laokoon and his Sons, by Hagesandros, Polydoros, and Athanadoros, late 1st c. B.C. to early 1st c. A.D. The great group known as the Laokoon, found in Rome in A.D. 1506 with Michelangelo in attendance, has had great influence on Western art. Although it has seemed at first glance to be the group mentioned by an ancient source as made by three Rhodian artists, Hagesandros, Athanadoros, and Polydoros, modern scholars have moved its date up and down from the second century B.C. to the first century of the Christian era, and have even moved the elements of the composition about. Most recently they have settled for a date late in the first century B.C. or early in the first century A.D...Fully 1.84 meters in height, the work depicts the death of the Trojan priest Laocoon and one of his sons as a result of his advice to the Trojans not to bring the Trojan Horse within the walls of their city. Laocoon and his two sons were attacked by giant snakes, and their struggles are graphically presented. Laocoon struggles against the enveloping coils, reacting to a savage bite with a distorted despairing face. The heavy musculature and distorted features remind one of the Pergamon frieze...To his right, Laocoon's younger son already collapses in death while to his left the older is extricating himself from the coils but looks back in horror at the other two. The composition can be easily taken in from a frontal vantage point, a characteristic of late groups, and can be interpreted as presenting a series of contrasts: man versus beast, maturity versus youth, life versus death. (Biers, pp. 313-14) ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Greek Architectural Orders The Doric and Ionic orders are the two major styles of Greek architecture. Both rely on a post-and-lintel system, but the Doric style is the plainer of the two. Its principal characteristics are a simple column shaft with twenty flutes and sharp divisions between (arrises), a capital with cushion-like lower part (the echinus) topped by a block-shaped slab (the abacus), and a triglyph-and-metope frieze above. The Ionic order is lighter and more slender than the Doric and more highly decorative. The Ionic column rests on an elaborately carved base. More slender that the Doric column, it has twenty-four flutes separated by flattened arrises rather than the sharp ones of the Doric order. The capital consists of two volutes with an ornamental area between. The frieze is continuous and either carved in relief or plain. The Corinthian order developed in the later years of the 5th century B.C. This order is a variant of the Ionic, differing from it mainly in its capital which is bell-shaped and decorated with spirals and carved leaves of acanthus, a plant with prickly leaves native to the Mediterranean area. The orders thus contain standard parts that relate to one another in a circumscribed system. Rules of proportion were formulated so that the appropriate size for each element could be derived from a dimension already decided. Rome's conquest of the Greek world in the second and first centuries B.C. opened Roman culture to Hellenic influences. The Greek architectural Orders were adopted, especially Corinthian, but functioned mainly as decorative elements. The use of concrete for walls and vaults freed Roman architects from the post-and-lintel construction employed by the Greeks, although Roman temples were often built in the traditional way. The Parthenon, Athens, Greece, 447-438 B.C. The Parthenon, the most famous example of Doric architecture, is justly regarded as the high point of the style. Constructed of Pentelic marble, it was built to house the gold-and-ivory statue of the Athena Parthenos made by Phidias. Sculptured pediments and metopes decorated the exterior, and a continuous frieze adorned the outside of the cella wall. Temple of Athena Nike, Athens, Greece, ca. 427 B.C. Built entirely of white marble, the little Ionic temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis was richly decorated with sculpture. The frieze reliefs have survived as have the relief slabs from a parapet surrounding part of the building. ________ MAA 5/96 GALLERY OF GREEK AND ROMAN CASTS Lysikrates Monument, Athens, Greece, ca. 334 B.C. The Lysikrates Monument, so-called because it was commissioned by Lysikrates, was built to commemorate a victory won by a theater chorus in 334 B.C. A bronze tripod, the triple-footed cauldron awarded as the prize in the contest, stood on the top. The circular monument is the earliest surviving example of the use of the Corinthian order on the exterior of a building. Temple of Olympian Zeus, Athens, Greece, 2nd c. B.C. and early 2nd c. A.D. This temple is notable for its Corinthian capitals. They may have had a strong effect on the Roman Corinthian order, for after the sack of Athens in 86 B.C. by the Roman general Sulla, some of the capitals were taken to Rome. In these capitals the bell is almost covered by acanthus leaves. Unfinished in the 2nd c. B.C., the building was finally completed under the Roman emperor Hadrian. Captions Plaster Models The Parthenon: Column, Capital and Part of the Entablature from a corner Capital from the Lysikrates Monument Temple of Athena Nike: Column, Capital, and Entablature from a Corner. Photographs The East Facade of the Parthenon today Temple of Olympian Zeus Corinthian Capital from the Temple of Olympian Zeus Lysikrates Monument The East Facade of the Temple of Athena Nike today ________ MAA 5/96