Managing Opportunities, Risk and Uncertainties in New

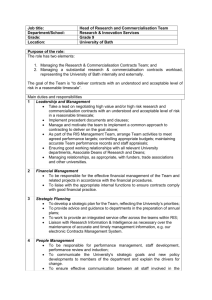

advertisement