Dealing With Breast Cancer: The Journals of

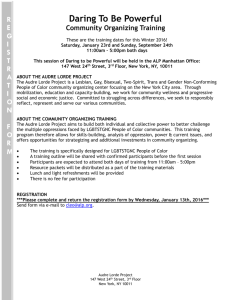

advertisement

Journal of US-China Public Administration, ISSN 1548-6591 June 2014, Vol. 11, No. 6, 548-556 D DAVID PUBLISHING Dealing With Breast Cancer: The Journals of Audre Lorde Caterina Riba Universitat de Vic—Universitat Central de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain This paper analyzes how Caribbean-American poet and activist Audre Lorde textualizes the experience of breast cancer in her journals. Lorde confronts the narrative of the female body provided by the biomedical approach and challenges the passive role she is expected to play as a sick person. She deplores misinformation to patients and the insistence on reconstructive surgery after a mastectomy. Lorde denounces the discursive aggression toward women that is the result of the hidden patriarchal impositions insidiously operating within medical practices. She believes medical discourse has often been used to implement many of the precepts that underlie a male-centered society, shaping the gendering of women in line with a patriarchal worldview. This paper examines how Lorde faced with such a hostile situation, managed to overcome it, by speaking up and putting her fears and her hopes into words. Her personal diaries, The Cancer Journals (1980) and A Burst of Light (1988), constitute today a fundamental point of reference and an important contribution to the feminist cause. Keywords: Audre Lorde, breast cancer, breast reconstruction, journals, medical discourse The idea that a medical discourse is the only discourse legitimized to discuss illnesses and there is no other reliable way to talk about the sick is inculcated in us at the deepest levels. Given that medical discourse uses “scientific” and “objective” methodologies that are supposedly unbiased, the “truth” it produces is regarded as unquestionable. The infallibility granted to medical discourse often leaves patients defenseless, unable to be an active participant in making sense of their disease and shaping their treatment (Mathieson & Henderikus, 1995; Espinàs, 2003; Charon, 2006). As the breast is often considered as a metaphor for femininity, the discourse around breast cancer is propitious terrain for reinforcing gender roles (Coll-Planas, Alfama, & Cruells, 2013). Patients are often left voiceless and doctors have authority to intervene in almost all aspects of women’s life, with the result that medical discourse can be used as another strategy of oppression helping Western patriarchal societies maintain the status quo. Since very early in the second wave of feminism, the relationship between women and the medical establishment has been an important question for both political action and scholarly enquiry. Early statements of these positions include, among others, the classic “Our Bodies, Ourselves” (produced in 1971 by what was originally known as the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective); the works of Barbara Seaman (1969; 1972), principal founder of the Women’s Health Feminist Movement; Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English’s (1973) study on the expulsion of female healers from the medical profession; Phyllis Chesler’s (1972) book on psychiatry and the feminine psyche; and Ellen Frankfort’s (1972) discussion of women and Corresponding author: Caterina Riba, Ph.D., associate lecturer, Applied Languages and Translation Department, Universitat de Vic—Universitat Central de Catalunya; research fields: comparative literature, gender studies, and translation studies. E-mail: caterinariba@gmail.com. DEALING WITH BREAST CANCER: THE JOURNALS OF AUDRE LORDE 549 gynecology. They all criticized condescending and non-informative doctors and urged women to learn about their bodies and participate in decision-making processes concerning their health. They took upon themselves the task of unmasking the discursive strategies that framed and enabled the accepted treatment of illness and deplored the systemic discursive violence directed toward those who represented otherness vis-à-vis hegemonic culture. Audre Lorde published her journals in 1980, just as certain discourses that had up until then been viewed as unquestionable began to be challenged. In fact, a complete worldview was being called into question, as notions such as objectivity and universality were debated, and absolute truths like those arising from medical discourse began to lose credibility. In response to an explanation of her illness that Lorde finds insufficient and unsatisfactory, she approaches the matter from a completely different angle, writing a personal diary, a genre that is the epitome of subjective expression. It seems that the proliferation of self-stories is the logical reaction to the wreckage and uncertainty of the narrative of postmodern times, which offers “no privileged, unproblematic position from which to speak” (Hutcheon, 2000, p. 153). The narratives of church, state and science that held societies together, what François Lyotard (1984) called “grandes narratives”, cannot provide the cognitive frame any longer. The illusion of the enlightenment, the possibility of achieving full knowledge, has shattered into fragments of memories and points of view. In the words of Arthur Frank: “Audre Lorde could only be who is in postmodern times, and these times are formed by people like Audre Lorde. Her narrative becomes the ethic of her times” (Frank, 1997, p. 167). This paper will study how Audre Lorde challenges traditional Western notions of illness and critically analyzes the narrative of the female body provided by scientific and medical approaches. The author will analyze how, in her journals, Audre Lorde shows that cancer treatments and breast reconstructions are not value-free and that they impose a certain idea of what a woman should be. We will focus specially on the insistence on having reconstructive surgery, still a pertinent debate nowadays since the first stage of the reconstruction can be done at the same time as the mastectomy, with the result that patients have almost no time to mourn their loss and make informed decisions. From Silence to Language and Action Audre Lorde, the self-described black lesbian warrior poet (Lorde, 1997, p. 19), spent her life questioning the assumptions around which society is organized. Born in Harlem in 1934, she embodied the invisible subject and dedicated much of her life and work to conquer the right to be heard, for her and others on the margins of hegemonic culture. Speaking up was in Lorde’s nature, as she explained in her article “The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action” (Lorde, 1998a), originally a speech delivered in 1977. Lorde believed she would be betraying herself if she remained silent and felt she had to seek out her own truth if she did not want to be judged, censored, or annihilated. She considered taboos harmful and believed silence would not shelter her, so she reacted and attempted to do something useful. Her outspoken attitude was not always approved of or shared by others. Lorde started publishing her poetry regularly in anthologies and literary magazines during the 1960s1, and became increasingly involved in feminist organizations. Once she had acquired a high public profile and her work had gained recognition, she 1 Her first volume of poetry The First Cities was published in 1968. 550 DEALING WITH BREAST CANCER: THE JOURNALS OF AUDRE LORDE was the target of malicious gossip and her reputation and prestige were often attacked. In 1971, for example, while she was teaching at John Jay College, becoming very popular among black students, some of her detractors tried to discredit her by exposing her as a lesbian, the implication being that she was not suited to discuss and could not possibly represent positive notions of blackness. As a response to the accusations, and well aware that silence can prove a powerful weapon in enemy hands, she posted her transparently lesbian “Love Poem” (Lorde, 2000, p. 127) on the wall of the English Department, and also decided to have it published in Ms. Magazine (Wylie Hall, 2004, p. 61). Lorde is also known for being the first one to denounce racism within the feminist movement. In the Second Sex Conference, which took place in Chicago in 1979, Lorde criticized the marginalization of colored, lesbian, and non-Western participants, who had been excluded from the main conference program. In her speech, later published as part of her collected essays in Sister Outsider under the title “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House”, Lorde questioned some feminist assumptions: Now we hear it is the task of woman of color to educate White woman—in the face of tremendous resistance—as to our existence, our differences, our relative roles in our joint survival. This is a diversion of energies and a tragic repetition of racist patriarchal thought. (Lorde, 1998b, p. 113) When she was diagnosed with cancer, she also broke the silence imposed upon her and shed light on the ways in which sick subjects, particularly women, are rendered passive objects by the medical establishment. She deconstructed and reconstructed the role of the sick and advocated for women’s right to make their own decisions about their health. Lorde was willing to face death as she had life: courageously. Her attitude toward breast cancer is consistent with her life-long feminist activism. Having cancer did not stop her from working, and during the last decade of her life, she participated in many projects. She was involved in the work of Sisters in Support of Sisters in South Africa (SISA), an organization founded in 1984 by the writer and activist Gloria Joseph. In 1987, Lorde and Joseph moved to St. Croix, the largest of the U.S. Virgin Islands, in the Caribbean, from where Lorde’s family originated, and together they founded the “Women’s Coalition”. She was there when hurricane Hugo struck, causing incalculable suffering and great economic loss in the island, and Lorde harshly criticized the management of the disaster by the U.S. Government. Later on, she contributed to the book about the hurricane entitled Hell Under God’s Orders (Joseph, 1990), edited by Gloria Joseph. Audre Lorde died of cancer in St. Croix on November 17, 1992, at the age of 58 years old2. The Cancer Journals by Audre Lorde Audre Lorde was a pioneer in articulating the female experience of breast cancer3. This disease became the focus of medical research throughout the 20th century, after health problems such as infections, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases were no longer fatal. Cancer appeared then as the main incurable disease, together 2 For further information about the poet’s life and legacy, read Warrier Poet. A Biography of Audre Lorde by Alexis de Veaux. There is also a chronicle of Lorde’s life, a “biomythography”, written by the author herself: Zami. A New Spelling of my Name. She also featured as the subject of a documentary called A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde (1995) directed by Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson after they had been collaborating with the poet for eight years. There is another documentary about her, The Edge of Each Other’s Battles: The Vision of Audre Lorde (2002) directed by Jennifer Abod. 3 Susan Sontag had published Illness as Metaphor in 1978. Sontag argued that metaphors and myths surrounding cancer add to the suffering of patients and thought the most truthful way for regarding illness was the medical discourse, which she believed to be purified of metaphorical thinking. Adrienne Rich had also written some poems about cancer in her book The Dream of a Common Language (1978). DEALING WITH BREAST CANCER: THE JOURNALS OF AUDRE LORDE 551 with AIDS, and received a great deal of attention from biomedical sciences. In the US, pharmaceutical companies dramatically increased their research programs in the early 1970s4. At the same time, as has already been mentioned, the biomedical discourse began to lose the monopoly of knowledge concerning the sick body and, from the decade of the 1980s, social science researchers explored the matter from a different perspective (Hydén, 1997; Pierret, 2003). Not only did scholarly studies proliferate, but self-stories narrating the experience of the disease did so as well, among them Audre Lorde’s groundbreaking writings. Some of the questions raised by Lorde have lost none of their relevance: The need to address the disease from a holistic approach, the contention that more emphasis should be put on prevention (not only from an individual point of view), the demand for patients to be better informed and the criticism of the insistence that women seek an artificial cosmetic remedy after mastectomy are issues still subject to debate today. Lorde’s book The Cancer Journals was motivated by the stark disconnect between the information doctors provided her and her own feelings about the illness, and by her need to account for her experience. Lorde was unwilling to take on the “sick role” as Talcott Parsons had termed it in the book The Social System, first published in 1951. She refused to do what was expected of her, “to seek technically competent help, namely, in the most usual case that of a physician, and to cooperate with him in the process of trying to get well” (Parsons, 1991, p. 437). She wanted to actively participate in conferring meaning to the experience and in making decisions which affected her. The entries began in January 1979, six months after she underwent a mastectomy. The book opens with the following statement: I am a post-mastectomy woman who believes our feelings need voice in order to be recognized, respected, and of use. I do not wish my anger and pain and fear about cancer to fossilize into yet another silence, nor to rob me of whatever strength can lie at the core of this experience, openly acknowledged and examined. (Lorde, 1997, p. 7) Lorde believed that the personal is political and that what she felt compelled to explain could transcend her daily life and be helpful to those who suffered from isolation and loneliness, in addition to cancer. Her way of dealing with cancer, of retaining a measure of control in the face of uncertainty, consisted in transforming that overwhelming experience into language by writing it down. “My work kept me alive”, she stated (Lorde, 1997, p. 11). Lorde explained that, while she was in treatment, she could not write poetry, so in order to find some inner peace, she tried to channel and transform the enormous amount of energy raised by the experience: “I am learning to live beyond fear by living through it, and in the process, learning to turn fury at my own limitations into some more creative energy” (Lorde, 1997, p. 13). Lorde wrote about her distress and anxiety in order to let other women with cancer know they were not alone. She believed her work could provide them with words to help articulate what they were going through. She could not lean on the written accounts of women in similar situations—there were none available—and therefore, wanted to provide her own for future generations: “Where are the models for what I am supposed to be in this situation? (…) This is it, Audre. You are on your own” (Lorde, 1997, p. 28). There is a paradox in illness, as it is “the most individual and the most social of things”, as French anthropologist Marc Augé (1995, p. 24) points out. After The Cancer Journals was published, countless readers 4 A major step was taken when the National Cancer Act was signed into law in 1971 (P.L. 92-218). The National Cancer Program was created and the cancer-related activities of both governmental agencies and the private sector were then to be coordinated by the Director of the National Cancer Institute. For further information, consult the President’s Cancer Panel Report 2010-2011 published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 552 DEALING WITH BREAST CANCER: THE JOURNALS OF AUDRE LORDE wrote to thank her for writing her journals, which today constitute a reference work, so we can only conclude that she was right in identifying the need for such a work, and that it was a useful contribution to the feminist cause. She also published the second diary entitled A Burst of Light (Lorde, 1988), with excerpts from 1984 to 1986, after she learnt she had liver cancer, which had metastasized from her previous breast cancer. She also wrote articles and poems on the topic, participated in discussion groups about it, and analyzed it in an interview with Dagmar Schultz, included in Conversations With Audre Lorde (Wylie Hall, 2004). According to Lorde, cancer is a painful reminder of our human condition and our mortality, and it is also a wake-up call underscoring our responsibility to live on our own terms. For Lorde, learning how to die teaches us how to live. We all carry death around with us, yet incorporating such a thought without spoiling our existence is a challenge. In her diary, Lorde poses the question: “There must be some way to integrate death into living, neither ignoring it nor giving in to it” (Lorde, 1997, p. 11). Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman states that death is impossible to construe conceptually and that it is intrinsically unthinkable even though we all know it is real. He argues that consciousness of one’s mortality is traumatic because death is the “ultimate absurdity” and the “ultimate truth” at the same time, the result being the eviction of death from life (Bauman, 1992, p. 15). Audre Lorde believes we should accept mortality no matter how absurd it may be. She claims the consciousness of our mortal condition can make us vulnerable, but it can also make us strong; we can learn how to use the power stemming from such a revelation to build a life which is true to ourselves and to help us make the right choices. Information Is Empowering Lorde wrote down her thoughts and feelings about the illness throughout the whole process. After she was told she needed a biopsy and that the chances it would reveal a malignant tumor were 80%, Lorde and her partner Frances Clayton went to see several doctors until they found one who took the time to answer all their questions, regarded their relationship without prejudice, and treated Frances Clayton as Audre Lorde’s next of kin. In her small room at the hospital, the books piled up as Lorde avidly read anything and everything that could help her make informed decisions. She did not know whether she wanted to undergo surgery or if she preferred chemotherapy and radiation. Even though she considered surgery as the best option in terms of survival, she was very reluctant to have a breast removed: “I wanted time to re-examine my decision, to search really for some other alternative that would give me good reasons to change my mind. But there was none to satisfy me” (Lorde, 1997, p. 28). After giving a lot of thoughts, Lorde had a mastectomy: “The decision whether or not to have a mastectomy ultimately was going to have to be my own. I had always been firm on that point and had chosen a surgeon with that in mind” (Lorde, 1997, p. 29). Some years later, she was diagnosed with liver cancer, she looked for information about alternative homeopathic treatments. She met an anthroposophic doctor in Spring Valley (New York), someone who combined conventional medicine with homeopathy and naturopathy, and he suggested she sought treatment at Lukas Klinik, a hospital in Switzerland, where she wrote her second diary. The holistic approach to cancer treatment seemed to fit Lorde’s ideal, changing her habits and her diet, and taking care of her soul and her emotional needs as well as her body. For a while, Lorde received naturopathic treatment in Europe at the same time as conventional medical treatment in New York and she had to decide for herself when advice was contradictory. DEALING WITH BREAST CANCER: THE JOURNALS OF AUDRE LORDE 553 Lorde’s aim when she explained how she reached decisions was not to convince anyone to follow any specific course of treatment, but to let other women know they did not have to surrender control of their body to others and that they were entitled to make their own choices. Through her journals, we learn Lorde was lonely and terrified, yet sought to confront the situation on her own terms. She wanted to take responsibility for her decision-making, which was certainly exhausting, especially because her survival might have depended on it: “I think now that what was most important was not what I chose to do so much as that I was conscious of being able to choose, and having chosen, was empowered from having made a decision” (Lorde, 1997, p. 32). According to Lorde, access to information is a crucial means of empowerment for women. She maintained that cancer “is a feminist concern because there is work that can be done as women, informed women” (Wylie Hall, 2004, p. 135). Committed to the cause and after having researched the topic, she wrote on the different options for treatment. One of the purposes of Lorde’s work was to inform about the choices available for women with cancer. She maintained that this information should be disseminated widely and suggested it be published in popular magazines, using accessible language. Again, Lorde was a visionary, since the amount of informative literature today is enormous (self-help books, testimonies, information on alternative therapies, articles in the media, internet forums, etc.), and it is dynamic and participatory. Lorde considered cancer not only from the perspective of treatment, but also from that of prevention, and criticized governmental in action regarding the regulation of carcinogenic compounds: Cancer is a political fact. And it’s necessary (…) for us to see what some of the implications are. The question of the relation between fat and breast cancer, or the kinds of pollutants that are carcinogenic—these are issues that we need to raise and protest against. (Wylie Hall, 2004, p. 135) Lorde’s demand is still valid. Much work needs to be done concerning research and legislation on environmental risk factors. The Cancer Panel Annual Report 2010-2011 found that: “An expanded understanding of the factors that influence cancer risk and progression is critically needed” and “More emphasis also is needed on areas of the cancer continuum beyond disease treatment, including prevention and early detection research and the long-term and late effects of treatment that often plague cancer survivors” (p. 15)5. In a nutshell, Lorde paved the way for many of the main present-day concerns about breast cancer. Breast Reconstruction The rebuilding of the breast after a mastectomy is also a topic Lorde examined closely. In her journals, she recounts two significant anecdotes. She explains that the day after surgery, a woman from Reach for Recovery, a program meant to help women cope with their breast cancer experience, went to see her and brought her a soft sleep-bra and a wad of lambswool. She suggested she wear that until she had her prosthesis implanted. The woman’s message was that if she could look the same as before, nobody would know the difference and she would be “just as good” (Lorde, 1997, p. 42). She had been through a mastectomy as well, but she proudly stated that thanks to a stiff brassiere, it was impossible for people around her to tell which was which. She also told her she had married her second husband six years after the operation and that having had a breast removed did not interfere with her love life if she wore an artificial breast mold. Even though she meant well, her words made Lorde feel deeply sad and lonely. For her, being one-breasted, painful as it was, was still more acceptable than using a lambswool molded cup and pretending that nothing had happened: 5 The full report can be consulted in: http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/, retrieved July 8, 2014. 554 DEALING WITH BREAST CANCER: THE JOURNALS OF AUDRE LORDE I ached to talk to women about the experience I had just been through, and about what might be to come, and how were they doing it, how had they done it. I needed to talk with women who shared at least some of my major concerns and beliefs and visions, who shared at least some of my language. And this lady, admirable though she might be, did not. (Lorde, 1997, p. 42) The second anecdote she recalls took place 10 days after the operation, when she went to her doctor’s office to have the stiches removed. A friend of her had washed her hair, she was wearing a new pair of leather boots and she was feeling quite confident and pleased with her style, all things considered. The doctor’s nurse called her into the examination room and anxiously pointed out that she was not wearing any prosthesis. When Lorde replied that it did not feel right, the nurse looked at her disapprovingly and told her that the lambswool puff was better than nothing and that she would be able to be fitted with a form after her stitches were out. She finally added: “We really like you to wear something, at least when you come in. Otherwise, it is bad for the morale of the office” (Lorde, 1997, p. 60). Lorde felt outraged and explained that “this was to be only the first such assault on my right to define and to claim my own body” (Lorde, 1997, p. 60). She became incensed over the fact that women actively trying to come to terms with their new bodily image were considered as a threat to the morale of the office of a top breast cancer surgeon in New York. She wanted to face her new condition, take the time she needed to confront the facts, mourn her loss, and make her own decisions. She had enough work with her own struggle to worry about strangers who had trouble dealing with the fact she had had a breast removed. She believed “this emphasis upon cosmetic after surgery reinforces this society’s stereotype of women, that we are only what we look or appear, so this is the only aspect of our existence we need to address” (Lorde, 1997, p. 58). Erving Goffman’s work on stigma shows that deciding when and to whom the “discreditable” person wants to reveal and share what makes him/her “not normal” is an extremely difficult situation because of its unpredictable consequences (Goffman, 1963). Lorde was well aware of this fact and claimed that managing one’s stigma was the “discreditable” person’s decision and not an imposition of those who felt uncomfortable when confronting “not normal” people. As a reaction to this insistence on cosmetic surgery, not only did Lorde refuse to have her breast rebuilt; she actually made her one-breasted figure a point of pride. She considered herself as an Amazon, a woman warrior whose wounds deserved respect: For me, my scars are an honorable reminder that I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers, and Red Dye No. 2, but the fight is still going on, and I am still a part of it. I refuse to have my scars hidden or trivialized behind lambswool or silicone gel. (Lorde, 1997, p. 61) Having to pretend or conceal reality was something she was not willing to do. True to her principles and her creative streak, Lorde was the first one to design clothes and jewelry for one-breasted women who did not wear a prosthesis. She considered this type of fashion, more attentive to the needs of a breast cancer survivor, a positive response to bodily change, rather than forcing it into artificial shapes that denied reality. She established an analogy of how patriarchal societies deny women their bodily experiences with the fact that maternity clothing had not always existed or been available to women, even though we now consider them as a necessity. Her venture into fashion design was featured in a 1979 issue of Ms Magazine, the feminist publication co-founded by Gloria Steinem, after which, according to Lorde, her designs gained popularity among those not only one-breasted women but also two-breasted women (Wylie Hall, 2004, p. 140). Lorde’s purpose was not to criticize women who chose to have surgery. Instead, she sought to denounce DEALING WITH BREAST CANCER: THE JOURNALS OF AUDRE LORDE 555 the oppression of women through the tyranny of appearance, which effectively makes women unable to freely decide about reconstructive surgery in the aftermath of a mastectomy. Lorde believed not enough emphasis was placed on the fact that this kind of surgery carries a risk of complications and might delay the detection of a recurrence of the cancer. Later, feminist scholars such as Nancy Datan, who also suffered from breast cancer, made Lorde’s words their own and carried on denouncing the pressure women experience to have their breast rebuilt. In 1987, Datan shocked her audience at Hamilton College as she started waving a large foam rubber prosthesis while standing at the podium to claim breast cancer was not a cosmetic disease (Crawford, 1997, p. 167). Datan’s reflections were developed in “Illness and imagery: Feminist cognition, socialization, and gender identity” (Datan, 1989), which has also become a fundamental text. Since then, the implications of undergoing reconstructive surgery have been widely explored from a feminist perspective (Wilkinson & Kitzinger, 1994; Pots, 2000). The photographer Jo Spence, well-known for her self-portraits taken while in breast cancer treatment and which were first exhibited in 1986, denounced in her book Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography: “Women are expected to be the object of the male gaze”, they “are expected to beautify themselves in order to become loveable” (Spence, 1986, p. 155). The British professors Sue Wilkinson and Celia Kitzinger, a couple that fought to have their relationship recognized as a marriage in England, expressed themselves in similar terms: The emphasis on sexuality and body image—meaning being attractive to men and engaging in sexual intercourse with them—is a major preoccupation of the psychiatric and psychological literature on mastectomy. There is very little discussion of other issues in relation to breast loss—breast feeding, or explaining (or concealing) the loss of a breast to a child, for example. (Wilkinson & Kitzinger, 1994, p. 126) Wilkinson and Kitzinger also deplored the fact that leaflets written by the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons were routinely given in the U.S. to post-mastectomy patients, the message being that their body was disfigured, and defective. Medical advances today allow immediate breast reconstruction to be started at the same time as the mastectomy (as can be read on the American Cancer Society website). If mastectomy and reconstruction are perceived as part of the healing process, there is even less room for a free choice. Conclusions In her journals, Lorde complained about doctors patronizingly attempting to impose their own preferences for treatment, without adequately informing her of the options or listening to her objections, in effect taking advantage of a situation of utmost vulnerability. Unprepared as we all are to cope with a devastating illness such as cancer, Lorde believed patients should, at a minimum, have access to relevant information concerning treatment options. Given that she was a writer of certain financial means, Lorde understood she was in a position to advance the cause of women patients, and saw it as her duty to share the knowledge she had acquired so that other women would be better able to make informed decisions about their illness. In her deconstruction of the experience of the sick female subject, Lorde also analyzed the cultural assumptions underlying the notion that women should conceal their mastectomy. In Western patriarchal societies, in which women are pressured into mistreating and punishing their bodies to conform to an idealized image of femininity, having had a mastectomy makes women inadequate; in order to reclaim their value as females, they must have their breasts reconstructed. This tyranny of appearance inflicted on women, as Lorde denounced, is another discursive aggression. 556 DEALING WITH BREAST CANCER: THE JOURNALS OF AUDRE LORDE References Augé, M. (1995). Biological order, social order; illness a primary form of event. In M. Augé and C. Herzlich (Eds.), The meaning of illness (pp. 23-71). Sydney: Harwood Academic Publishers. Bauman, Z. (1992). Mortality, immortality and other life strategies. Cambridge: Polity Press. Charon, R. (2006). Narrative medicine. Honoring the stories of illness. Oxford and New York: University Press. Chesler, Ph. (1972). Women and madness. New York: Avon Books. Coll-Planas, G., Alfama, E., & Cruells, M. (2013). Se_nos gener@ mujeres. La construcción discursiva del pecho femenino en el ámbito médico [Gen(d)erating women. The discoursive construction of the breast within the medical field]. Athenea Digital, 13(3), 121-135. Crawford, M. (1997). Talking difference: On gender and language. London: Sage Publications. Datan, N. (1989). Illness and imagery: Feminist cognition, socialization, and gender identity. In M. Crawford and M. Gentry (Eds.), Gender and thought: Feminist perspectives (pp. 175-189). New York: Springer-Verlag. De Veaux, A. (2004). Warrier poet. A biography of Audre Lorde. New York: Norton. Ehrenreich, B., & English, D. (1973). Witches, midwives and nurses. A history of women healers. Detroit: Black and Red. Espinàs, L. (2003). Análisis psicosocial de la interacción “profesional de la salud”/“paciente”/“familiar”. Unejemplo: el caso de los foros virtuales de autoayuda en cáncer (Psychosocial analysis of the interaction between health professionals/patients/relatives. An example: The case of online self-help cancer forums). Athenea Digital, 4. Retrieved from http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Athenea/issue/view/2790/showToc Frank, A. (1997). The wounded storyteller. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Frankfort, E. (1972). Vaginal politics. New York: Quadrangle Books. Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. Hutcheon, L. (2000). The politics of postmodernism. New York: Routledge. Hydén, L. C. (1997). Illness and narrative. Sociology of Health & Illness, 19(1), 48-69. Joseph, G. (Ed.). (1990). Hell under God’s orders: Hurricane Hugo in St. Croix—Disaster and survival. Saint Croix: Winds of Change Press. Lorde, A. (1982). Zami. A new spelling of my name. New York: Crossing Press. Lorde, A. (1988). A burst of light. New York: Firebrand Books. Lorde, A. (1997). The cancer journals. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. Lorde, A. (1998a). The transformation of silence into language and action. In A. Lorde (Ed.), Sister outsider: Essays and speeches (pp. 40-44). Trumansburg: Crossing Press. Lorde, A. (1998b). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. In A. Lorde (Ed.), Sister outsider: Essays and speeches (pp. 110-114). Trumansburg: Crossing Press. Lorde, A. (2000). The collected poems of Audre Lorde. New York: Norton and Company. Lyotard, J. F. (1984). The postmodern condition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Mathieson, C. M., & Henderikus, S. (1995). Renegotiating identity: Cancer narratives. Sociology of Health & Illness, 17(3), 283-306. Parsons, T. (1991). The social system. London: Routledge. Pierret, J. (2003). The illness experience: State of knowledge and perspectives for research. Sociology of Health & Illness, 25(3), 4-22. Pots, L. K. (Ed.). (2000). Ideologies of breast cancer. London: McMillan. Rich, A. (1978). The dream of a common language. New York: Norton. Seaman, B. (1969). The doctor’s case against the pill. New York: Peter H. Wyden. Seaman, B. (1972). Free and female. New York: Coward, McCann, and Geoghegan, Inc. Sontag, S. (1978). Illness as metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Spence, J. (1986). Putting myself in the picture: A political, personal and photographic autobiography. London: Camden Press. Wilkinson, S., & Kitzinger, C. (1994). Towards a feminist approach to breast cancer. In S. Wilkinson and C. Kitzinger (Eds.), Women and health: Feminist perspectives (pp. 124-140). London: Taylor & Francis. Wylie Hall, J. (Ed.). (2004). Conversations with Audre Lorde. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.