Credit Controls - Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

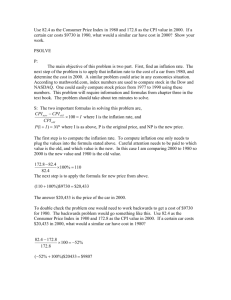

advertisement