Chain of Greed - National Employment Law Project

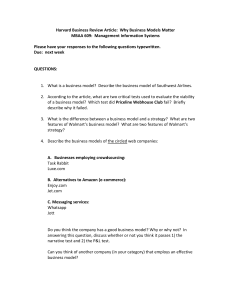

advertisement