Automotive Industry Analysis - the Systems Realization Laboratory

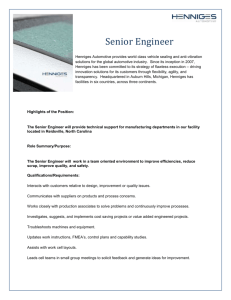

advertisement