European Psychiatry 26 (2011) 11-14

Diagnosis and classification of mental disorders

in Russian speaking psychiatry: focus on affective spectrum disorders

V.N. Krasnov

Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry, Poteshnaya 3, Moscow, 107076, Russia.

ABSTRACT

Keywords:

Classification

ICD-10

DSM-IV

Psychopathology

Dynamic approaches in diagnostics

Psychopharmacological analysis

Affective spectrum disorders

Depression

Anxiety

PTSD

Somatoform disorders

Russian–speaking psychiatry

The paper deals with present-day classification of mental disorders regarded from the positions of

Russian-speaking psychiatrists. Consideration of depressive and anxiety disorders, in particular in

the context of a multi-year research within the settings of the primary care network, points to close

links between these disorders. The concept of a psychopathological commonality among affective

spectrum disorders is set forth with references to earlier studies and the data of other Russianlanguage writers. The affective spectrum disorders cover typical affective disorders, mixed anxiety

and depressive disorders, as well as somatoform and stress-related disorders.

Current classifications ICD-10 and DSM-IV reflect many

contradictory tendencies in recent developments in psychiatry.

The principal among them are as follows:

• necessity to use standard and internationally accepted diagnostic categories;

• simplification of diagnosis reached by counting symptoms of

disorder (operational diagnostics);

• prevalent static evaluation of disorders, i.e. identifying an

actual combination of symptoms at a certain moment of

time, as a diagnostic unit, instead of dynamic evaluation of

the syndrome.

• the impact of public perception on the classification or name

of disorders, the perception stemming from notorious bias or

prejudice with regard to psychiatry. There have been some

precedents when reciprocal striving of both psychiatrists

and associations of patients and their relatives brought about

radical suggestions of denying certain long-established medical diagnostic terms such as schizophrenia [1]. Rejection of

Correspondance.

E-mail address: krasnov@mtu-net.ru

© 2011 Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.

© 2011 Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.

generally accepted terminology is fraught with losing scientific

landmarks in both psychiatry and medicine as a whole.

The mentioned tendencies reflect utilitarian essence of the

classification as a technological facet of psychiatric practice.

And this is their difference as a consensus of experts from

psychopathology as a theoretical and conceptual level of

clinical analysis based on structural connections and dynamic

interactions of mental phenomena (both abnormal and natural,

including defensive and compensatory ones). To a certain degree

one can hardly expect obligatory correspondence between the

psychopathological (systemic) evaluation of some condition and

establishing its place in the nomenclature of mental disorders

recognized at concrete period of time.

Though the majority of Russian and Russian-speaking psychiatrists in Belarus, the Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic

and Armenia do recognize the advantages of the ICD-10 as a common language for psychiatrists all over the world, they are rather

critical about certain general and specific aspects of the ICD-10

and DSM-IV. They consider renunciation of nosology (as a basis

for classification), as a temporary retreat necessary for review

and analysis of data concerning etiology and pathogenesis of the

majority of mental disorders. Atheoretical character of the ICD-10

and DSM-IV is presented as renunciation of ideology, while the

12

V.N. Krasnov / European Psychiatry 26 (2011) 11-14

nosological clinical system initially developed by E. Kraepelin [2]

is considered as a variant of ideology. Actually, the nosological

system was a means of learning about morbid phenomena using

the knowledge, and data available in certain period of history.

Russian-speaking psychiatrists educated in accordance with traditions of classical clinical psychiatry, primarily German, French and

Russian, do not reject the nosological principle completely. They

still hope that a new nosology will arise as a unity of etiology,

symptomatology and the course of disease.

Methodology of diagnosis implies the development of

symptoms in time, grouping particular features, organizing

them in systematic way, finding internal relationships between

individual elements and observing the shaping of the syndrome.

The syndrome is understood as a dynamic formation with

changing structural ratios of symptoms. In an autochthonous,

spontaneous development of a disease, some symptoms may

come to foreground, some decrease or remain hidden, but still

present. This is an essential characteristic of syndromokinesis, or

syndrome trend. In the course of a relatively long-term observation and treatment the psychiatrist can observe the reshaping

and transformation of syndromes.

Psychopharmacological analysis, i.e. using medication both

as a treatment factor and a means of investigation, offers an

opportunity to study the psychopathological dynamics of the

syndrome and specify the diagnosis [3,4]. Thus, use of antipsychotics (olanzapine, risperidon or other) in paranoid schizophrenia may help to detect underlying depression. In other cases,

the use of antidepressants with a stimulating component for

the treatment of depression can reveal incongruent delusional

ideas (e.g. ideas of persecution) and thus cause alteration of

diagnosis and adjustment of treatment. Another example could

be relatively fast relief of seemingly dominant anxiety by means

of antidepressant medication with anxiolytic properties (like

trazodon, mianserin, mirtazapin), while the depressive “nucleus”

lags behind and gradually decreases two to three weeks after the

primary anxiolytic effect of the medication. Similar combined

treatment and diagnostic approaches we can find not only in

Russian clinical psychiatry [5].

Russian and Russian-speaking specialists still take efforts to

confirm the single nature of depression and majority of anxiety

disorders within frames of anxiety-depressive conditions despite

their current separate positions in the ICD-10 and DSM-IV as

depressive disorder and anxiety disorder.

Close clinical relationships between anxiety and depression have been formulated in traditional psychiatry [6-8]. It

is a well-known fact from psychiatric practice dealing with

recurrent depression that in every next depressive episode the

representation of anxiety components decreases while the representation of typically depressive ones (like diurnal variations

with morning worsening, diminished motivation for activity,

and feeling of guilt) increases. Clinically and epidemiologically

the distinction between long-term anxiety disorders and major

depression (specifically regarding first depressive episode) are

not clear-cut [9-12].

Our special research of affective spectrum disorders in

primary health care system in framework of the Programme

“Recognition and treatment of depression in primary care” [13]

also suggests transformation of anxiety disorders into depressive disorder within one continuum. Purpose was to study of

the prevalence of affective spectrum disorders in primary care

setting. Methods used are as follows: screening questionnaire,

semistructured psychiatric interview, SCL-90-R, Hamilton

Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17), Hamilton Anxiety Rating

Scale (HARS).

In 2000–2001 a screening of affective spectrum disorders

in several territorial (general medical) polyclinics in three cities

of Russia has been carried out. Subjects of investigation were

working or studying persons, aged from 18 to 55 years.

During the first stage, we identified with the help of a

7-item screening instrument a group of outpatients with

various affective spectrum disorders, including subthreshold

depression, anxiety and somatoform (psychovegetative) disorders. This group consisted of 2.749 persons (51.2%) of the

5.366 outpatients screened. They were offered a consultation of

a psychiatrist concerning their symptoms, in a special (so called

“psychotherapeutic”) room. 1.919 (35.8%) agreed to this proposal

and were interviewed by a psychiatrist. 1.616 (30.1%) cases of

those investigated were diagnosed as suffering from depression according to ICD-10 criteria for a depressive episode; in

1.334 cases (24.8%) severity of depression was 15 or more on the

Hamilton Depression Scale. Diagnoses distribution is presented

in Table 1. In accordance with the terms of the above-mentioned

Program, these persons could enter a 6-week course of medication with modern antidepressants, mainly with sertraline.

In about 90% of these cases depression dominated in patients’

condition but it was accompanied by subsyndromal or obvious

moderate anxiety disorders. At the same time, there were different combinations of depression with anxiety and somatoform

disturbunces--with similar score levels of somatization, depression and anxiety by SCL-90-R. As for prevalent anxiety disorders

(like generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder), they were

diagnosed only in 238 (4.4%) persons. Somatoform disorders

were mostly preliminary diagnosed for further observation.

In 2002-2003, a second screening with subsequent diagnostic

procedure and following the same research design took place

in two policlinics. Screening covered 4.020 persons, and 2.046

(50.9%) had signs of affective spectrum disorders. A psychiatric

interview helped to detect 1178 (29.3%) cases of depression,

including 992 cases (24.7%) with score 15 and higher on the

Hamilton Depression Scale.

138 of the latter subgroup had previously been included

in the sample of previous research in 2000 - 2001, and 34 of

them then had been diagnosed as anxiety disorders, including

9 cases of “generalized anxiety disorder” (GAD), 19 cases of

“panic disorders” and 6 other cases of anxiety disorders.

At the period 2002-2003 the above mentioned cases met

the criteria of depressive episode. Former dominated anxiety

Table 1

ICD-10 diagnoses distribution of depressive disorders in primary care.

F 32

Depressive episode

31.2%

F 33

Recurrent depressive disorder

24.1%

F 34

Chronic depressive disorder

(mainly “double depression” within dysthymia)

26.3%

F 41.2

Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder

11.0%

F 43.21

Long-term depressive reaction

3.1%

Others

4.3%

V.N. Krasnov / European Psychiatry 26 (2011) 11-14

happened to be on subordinated position because of pronounced

symptoms of depression.

In 2004-2005 more 28 cases of anxiety disorders from

observed sample have been changed for diagnosis “depression”,

including 13 with former diagnosis GAD. Besides during the

period of observation a part of patients with mixed anxiety and

depressive disorder entered for secondary consultative aid,

and their condition turned out more close to strict criteria of

depression. It is noteworthy that the so-called social phobia was

hardly considered as a basis for seeking help within primary care

system. Separate somatoform disorders without (sub) depressive

and anxiety features were also identified in rare cases.

Thus, one can suggest a tendency for transformation of affective disorders in the course of time or subsequent episodes – from

prevalent anxiety symptoms to mixed anxiety – depressive

condition, and further on to depressive syndrome per se. It seems

like another argument in favor of single pathogenetic entity for

majority of affective spectrum disorders. Then anxiety shows at

the initial stage or as the foreground primary affect that tends

to evolve in direction of typical depression.

On the basis of our previous study on psychopathology and

dynamics of different types of depression [14] we suggest, and

this suggestion is confirmed by the data from primary care, that

depression has several stages of development. Those are:

• Prodrome with non-specific symptoms of emotional and

vegetative instability;

• Anxious stage including three substages:

Ⱦ situation anxiety with a concrete cause,

Ⱦ free-floating anxiety with changing subjects of anxiety,

mainly determined by chance,

Ⱦ anxiety with no cause (without subject);

• Depressive stage including three substages:

Ⱦ depression with “anxious” elements within sadness

condition,

Ⱦ depression with hidden anxiety, but with domination of

sadness,

Ⱦ depression with areactivity / hyporeactivity and psychomotor retardation.

Operational diagnosis registers only a concrete stage at the

moment the patient is seeking help. Identifying dynamic aspects

of diagnosis seem to be a task for future classifications.

A dynamic hierarchy and multiple interrelationships

between depression and anxiety should be taken into account

in the development of future psychiatric diagnostic systems.

It could be functional diagnostics, which consider, anxietydepressive affective disorder as cohesive entity, a kind of clinical

continuum from adjustment disorders with protracted anxiety

and depressive symptoms to severe melancholic depression.

The symptoms of GAD share many features with depression

and often represent the prodromal phase of depressive episode.

More or less similar relationship can be revealed between panic

disorder at the whole context and affective spectrum disorders. The

differences are much more connected with physiological (including

emotional and vegetative) reactivity than psychopathology itself.

There are also some specific problems Russian and Russianspeaking psychiatrists face while using ICD-10. Regarding the affective spectrum disorders more few categories should be considered.

Majority of Russian-speaking psychiatrists, especially those

who have much experience in treatment of victims of large-scale

13

disasters, military combat or terrorist attacks are critical about a

wider application of the clinical diagnosis “post-traumatic stress

disorder” (PTSD) [15-18]. A significant part of conditions identified in English-language publications as PTSD are interpreted in

Russia in a different way: primarily as long-term depression, or

polymorphic conditions, or a combination of dysthymia, mild

cognitive disorders, personality deviations and psychosomatic

dysfunctions, sometimes with excessive alcohol consumption or

drug abuse. The nature of such disorders is understood rather as

multifactorial, and not exclusively psychotraumatic. For instance,

in the persons involved in elimination of the consequences of the

Chernobyl disaster in 1986, persistent disorders developed as a

response to a combined (synergic) effect of a number of harmful factors while every single factor was not really pathogenic.

Among them are extreme psychological and physical tension,

disrupted biological rhythm in the first months after the disaster

because of hard work in shifts associated with construction of

protective “sarcophagus”, exposure to low doses of radiation

(insufficient for development of radiation disease), dust, polluted

air, especially in the environment of miners digging a tunnel

under the destroyed nuclear reactor, other unfavorable factors

connected with emergency work in Chernobyl. Many of the

rescue workers experienced asthenic, psychovegetative, affective spectrum disturbances or stable disorders for the long time

[19]. But official medicine didn’t find some specific reason and

specific “name” for their morbid condition. It didn’t meet criteria

of radiation disease and didn’t meet full criteria of PTSD. Their

symptomatology in development with tendency of worsening

intellectual and physical productivity was much more close to

so called organic psychosyndrom by E. Bleuler [20]. Similar ideas

about multiple nature and polymorphism of symptomatology

of the post-traumatic stress disorders are rather rare but can be

found in current English-language literature [21,22].

There is a semantic inaccuracy that should absolutely be

deleted from the future ICD-11: it has to do with the categorization of stress related disorders (F 43). It has been formulated as

“reaction to severe stress”. This seems illogical because «stress»

in itself is a “reaction” of adaptation to changing environment.

More appropriate could be use the common category stress

disorders.

According to opinion of the most of Russian speaking psychiatrists, the category “somatization disorder” (F45.0) has no

real clinical ground and is contradictory in itself. The point is that

somatization is not a state but the process of involvement of different somatic functions (vegetative, metabolic,neuroendocrine,

immune, trophic) into pathological condition. According to

tradition [23,24], somatization can be interpreted as reflection

of primary affective disorders (anxiety and depression) on

vegetative-somatic level. Historically the notion “somatization

disorder” is only other name of “conversion disorder”, that consider psychodynamic interpretation of psychogenic or neurotic

disturbances in old terminology. “Somatoform disorders” in

the whole are very common, mostly as somatoform autonomic

dysfunction (F 45.3) as usual with subaffective ground.

Declarations of interests

The author has no interests that may be affected by the

publication of this paper.

14

V.N. Krasnov / European Psychiatry 26 (2011) 11-14

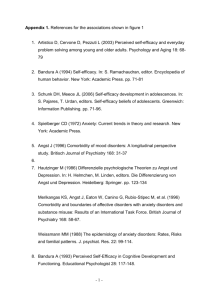

References

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

Van Os J. A salience dysregulation syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:101-3.

Kraepelin E. Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie. A. Barth, Leipzig. 1896.

Avrutsky GY, Neduva AA. Treatment of mentally ills: Guideline for physicians. Moscow: Meditsina; 1988.

Krasnov V, Gurovich I. Current state of Russian psychiatry. In: Bhui K,

Bhugra D, editors. Culture and mental health. A comprehensive textbook.

London, UK: Hodder Arnold; 2007. p. 109-21.

Fink M, Taylor MA. Melancholia: the diagnosis, pathophysiology and

treatment of depressive illness. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press; 2006.

Schneider K. Klinische Psychopathologie. G. Stuttgart: Thieme Verlag; 1962.

Lewis A. The state of psychiatry: essay and addresses. New York: Science

House; 1967.

Weitbrecht HJ. Psychiatrie im Grundriss. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1973.

Regier DA, Rae DS, Narrow WE, Kaelber CT, Schatzberg AF. Prevalence

of anxiety disorders and their comorbidity with mood and addictive

disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1998;34:24-8.

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence,

severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National

Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:617-27.

Wittchen HU, Kessler RC, Pfister H, Lieb R. Why do people with anxiety

disorders become depressed? A prospective-longitudinal community

study. Acta Psychatr Scand 2000;102:14-23.

Preisig M, Merikangas KR, Angst J. Clinical significance and comorbidity

of subthreshold depression and anxiety in community. Acta Psychiatr

Scand 2001;104:96-103.

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

Krasnov VN. The Programme “Recognition and treatment of depression

in primary care settings”. Soc Clin Psychiatry 1999;4:5-8.

Krasnov VN. Principals of dynamics of depression: clinical, pathogenetical and therapeutical aspects. In: Smoulevich A, editor. Depression and

comorbid disorder. Moscow, Russian: RAMN; 1997. p. 80-97.

Evsegneev RA. Psychiatry for general physician. Minsk: Belarus; 2001.

Sukiasyan SG, Tadevosyan AS, Chshmarityan SS, Manasyan NG. Stress

and post-stress disorders. Yerevan: Asogik; 2003.

Morozov AM, Kryzhanovskaya LA. Clinic, dynamics and treatment of

mental disorders in «liguidators» of disaster at Chernobyl NPP. Kiev:

Russian Chernobylinform; 1998.

Kokhanov VP, Krasnov VN. Psychiatry of disasters and emergency situations. Moscow: Prakticheskaya Meditsina; 2008.

Krasnov V. Psychopathological consequences of the Chernobyl disaster as a subject of ecological psychiatry. It J Psychiatry Behav Sci

2004;14:9-13.

Bleuler E. Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1916.

Everett B, Ismail K, David A, Wessely S. Searching for a Gulf War syndrome

using cluster analysis. Psychol Med 2002;32:1371-8.

McFarlane AC. Psychiatric Morbidity following disasters: epidemiology,

risk and protective factors. In: Lopez-Ibor JJ editor. Disasters and Mental

Health. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & sons; 2005. p. 37-63.

Lesse S. The multivariant masks of depression. Am J Psychiatry

1968;11:35-40.

Lopez Ibor JJ. Larvierte Depressionen und Depressionsaequivalente. In:

Kielholz P editor. Depressive Zustaende. Bern, Stuttgart, Wien: Verlag

Hans Huber; 1972. p. 38-43.