Definance Against Conventionality in 'Jane Eyre'

advertisement

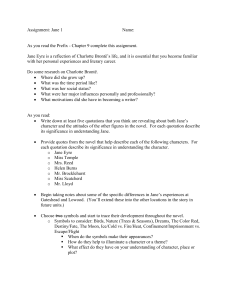

Adetunji 1 Funmi Adetunji Ms. Beall-Read English 10 G/T 12 May 2010 Defiance against Conventionality in Jane Eyre In a time when women were in essence social embellishment (Lowes), the rigid class system increased social limitations (Schwingen), and the imposed values of the religious movement had widespread dominance (Glasser), Victorian writer Charlotte Brontë rebelled. Feeling suppressed by society, Brontë withdrew into her fictional world, where she expressed her innermost beliefs. It was through her discontent with society that Jane Eyre, Brontë's "tour de force," was born (Lowes). In Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë reflects the beginnings of modernism in Victorian society in her unconventional portrayal of an independently thinking heroine who resists traditional class structures and customary religious beliefs. One of the ways in which Brontë resisted society's repression of women was through the strong voice of her heroine. To allow a fictional woman free reign of mind and spirit was a daring feat for a female author in the nineteenth century. Therefore, Brontë adopted a genderneutral pseudonym, which gave her greater freedom to express her views (Lowes). Jane Eyre is told in first-person, with emphasis on the female narrator's feelings and attitudes (Mayer). For example, when Jane and Rochester first meet, the narrator's confident "I" statements and inner reflections make Jane's thoughts the center of attention (Mayer). Placing such importance on a female narrator's point of view was seen by many as a challenge to the gender rules of society, and Jane Eyre was strongly criticized (Mayer). A tone of female rebelliousness can be found as well in Jane's authoritative manner (Oates v). As stated by Joyce Carol Oates, Jane exercises Adetunji 2 control over her narrative by influencing the reader's perception of events to her liking (xii). Also, for Jane, opposing the terms of her destiny is not unusual – as a girl she claims to have "resisted" her punishment in the red-room by Mrs. Reed (Oates v). Finally, Jane's blunt and direct way of speaking seems audacious in the context of the times (Oates vi). Young Jane boldly confronts her Aunt Reed after she is unfairly punished, calling her a "hard-hearted" and "deceitful" woman (Brontë 34). Later in the book, Edward Rochester is fascinated by Jane's "forthright wit and intelligence" ("List" 22). The strong female voice in Jane Eyre demonstrates nonconformity in Brontë's society (Mayer; Rigby 29). Brontë showed similar resistance through her heroine's unconventional desire for freedom and excitement. Through Jane's voice she spoke for constrained women everywhere (Lowes), while justifying her own hunger for adventure. Jane claims "restlessness" is in human nature, and although society expects women to be tranquil, they need activity just as men do (Brontë 114, 115). Moreover, Jane shows a constant need for change in setting (Brontë 114), revealing Brontë's belief in achieving absolute contentment (Lowes). After conditions at Lowood Institution are greatly improved, Jane spends two years teaching but soon longs for "liberty," a more fulfilling vocation (Brontë 88). Suddenly desiring change, Jane accepts a position as a governess at Thornfield Hall, where again she feels restless. Although generally pleased with her life at Thornfield before meeting Rochester, she feels it lacks "fire" and "feeling" (Brontë 114). Jane also struggles to protect her personal and emotional freedom by escaping situations that are restricting and embracing those that offer freedom. She refuses to be missionary wife to the controlling St. John Rivers but marries Rochester, who does not restrain her passions (Johnson). By depicting Jane Eyre as unabashedly adventurous, Brontë challenged the limitations society impressed upon women (Lowes). Adetunji 3 Furthermore, Jane shows autonomy in her fight for equality in male-female relationships. In opposition to societal ideals, Jane does not sacrifice her moral principles or self-worth regardless of the benefits of “wealth, status, or love” (Lowes). For instance, after realizing her marriage to Rochester cannot be lawful and will mean surrendering her sense of dignity and virtue, she leaves him (Lowes). Brontë ultimately rewards Jane for sacrificing love for her selfrespect by letting her return to Rochester after his "isolation" and physical dependence on her make them equals (Williams 21). The two live together in "perfect concord” and pure contentment at last (Johnson). However, because Jane cannot reach equality in her relationship with St. John Rivers, she rejects him permanently. When St. John proposes Jane join him in India as his missionary partner, Jane refuses; she will not sacrifice herself to serve a man for the sole incentive of moral duty ("List" 21-22). Likewise, Jane must escape the tyranny of Mr. Brocklehurst, the supervisor at Lowood Institution. Brontë promptly cuts Brocklehurst off from Jane's life after he degradingly places her on the "pedestal of infamy" while telling the school she is a liar (Williams 12). The following spring, the outbreak of typhus exposes Brocklehurst's negligence and causes him to lose his position (Williams 12). Jane's various experiences demonstrate Brontë's avant-garde view that mutual respect is the foundation for proper malefemale relationships (Lowes). Many Victorians saw Jane Eyre as an expression of Brontë's discontent with the social class structure (Lowes). According to a critic from the London Quarterly Review, Jane Eyre is a subtle protest against the traditional social order (Rigby 29). In her writing, Brontë critically portrayed the extent of the suffering of the poor with a sense of injustice (Schwingen). This is exemplified in Jane's account of the miserable conditions at Lowood Institution, a charity school for underprivileged girls (Williams 11). Jane remembers strongly how she and many others Adetunji 4 suffered from inadequate nutrition and the lack of proper clothing to protect them from the harsh winter cold (Brontë 60). Brontë also revealed negativity towards the class structure through Jane Eyre's analysis of class attitudes (Eagleton 57). Living as a lowly governess in a wealthy household gives Jane an "ambiguous class status" and subjects her to the discrimination of others (Mayer). For example, the upper class Ingram ladies treat Jane with disdain at a party due to her social inferiority as a governess (Brandon 12), emphasizing the class distinctions within the household (Mayer). The critical portrayal of class attitudes in Jane Eyre serves as the author's protest against the "class-based" social system (Glasser). Brontë's desired withdrawal from the restrictions of society manifested itself in the “persona” of her heroine (Lowes). This is shown in Jane's isolation from family ties, which gives her freedom to shape her own social destiny (Eagleton 55). Because of her childhood dependence on the Reeds for food and shelter, her "given relationship" with them is patronizing and hostile (Eagleton 55). Consequently, Jane disowns them as her relations and resolves to start afresh, this time relying on her own abilities. She attempts to recreate her own society by forming relationships that have value to her. Spiritually, Jane finds kinship with Rochester, although society separates them (Eagleton 55). Jane also discovers her family connection to Diana and Mary Rivers, who unlike the Reeds treat Jane with kindness (Eagleton 56). With success, Jane is able to support herself through her personal abilities (Eagleton 55). For instance, after fleeing the confining walls of Lowood, she takes a position as a governess at Thornfield Hall (Brontë 113). Following Thornfield, Jane supports herself as a schoolteacher in Morton, making enough to live on her own (Brontë 389). Brontë makes a statement in Jane's selfsufficiency despite her detachment from fixed social ties (Eagleton 55). Adetunji 5 Despite her disapproval of the British social system, Brontë's heroine promotes fighting to succeed within her “class-conscious” society (Mayer). Jane's primary goal is to "elevate her own social standing" (Schwingen); believing that love binds her to the wealthy Rochester, though “rank and wealth” separate them (Eagleton 55). Jane resists her social identity through her sense of personal dignity. Although her work as a governess brands her as inferior (Brandon 2), Jane's positive mindset transcends her lowly status (Schwingen). For instance, when living destitute on the streets, Jane manages to distinguish herself as an "educated" beggar (Eagleton 57). Also, she protests to Rochester that although she is “poor” and “obscure,” she deserves to be treated as a person with a heart and soul (Bronte 194). In spite of obstacles, Jane does end up climbing the social ladder; she inherits a fortune of twenty thousand pounds from a newly discovered relation (Williams 19). This allows her to return to Rochester an independent woman, his social and financial equal. Jane's ultimate success proves the ability of an individual to rise above the restrictions of the class system (Lowes). Charlotte Brontë's final purpose in Jane Eyre was to resist the influence of Victorian morality and religious values. As George P. Landow states, the Evangelical Protestantism Movement was characterized by "an emotional, imaginative comprehension of both one's own innate depravity and Christ's redeeming sacrifice" (Glasser). Brontë believed the "loss of true spirituality" was the result of "extremism" and flawed religious ideals (Glasser). Jane Eyre's rejection of various models of religion offered by other characters embodies this view. Her earliest model is Helen Burns, her childhood friend from Lowood, whose "consuming spirituality" is unbearable for Jane (Williams 12). She admires Helen for her purity and intelligence, but disagrees with her belief that happiness only comes through death (Williams 12). Mr. Brocklehurst, the supervisor of Lowood Institution, demonstrates a more condemnable Adetunji 6 religious doctrine. An extremist, Brocklehurst forces ascetic conditions, such as near-starvation, and rigid religious instruction to foster spiritual purity in his students (Brontë 63). He shows hypocrisy by claiming to detest vanity but supporting his own luxuriously rich family at the expense of the Lowood students (Brontë 65; Glasser). Later on, Jane meets “zealous minister” St. John Rivers, whose devotion to moral duty Jane finds suppressive (Glasser; Benvenuto 47). She hears him preach but dislikes his sermon because it dwells on the depravity of mankind (Brontë 381). Brontë's negative attitude towards Victorian religious values is shown in Jane's appraisal of various religious models (Glasser; Williams 12). In response to her perceived lack of real spirituality in society, Jane hungers for spiritual fulfillment (Brontë 381). Her personal search for God begins as a child when she questions Helen Burns about God and heaven. Hoping for insight, she inquires who God is and if a heaven truly exists, but Helen's mature answers leave her mystified (Brontë 84). Jane also sees and identifies with the lack of "true spirituality" in others (Glasser). For example, she suspects that minister St. John Rivers, though "pure-lived and conscientious," has yet to find peace with God (Bronte 380). She can relate to his spiritual hunger (Glasser). However, Jane finds a spiritual understanding apart from Evangelical principles. She experiences a personal encounter with God when she prays for guidance and feels that her prayer has been heard. Jane remarks that her prayer strongly differs from St. John's but is effective (Brontë 457). Brontë uses the spiritual maturation of her heroine to show that spiritual fulfillment exists outside of Evangelicalism (Brontë 380). By the novel's resolution, Jane Eyre has learned to follow her own moral standards that deviate from society's "fixed moral code" (Benvenuto 48). Jane's moral philosophy has defining characteristics, including the belief in the value of earthly pleasure (Williams 21). She believes Adetunji 7 it is God's will for her to return to Rochester, to choose a life of earthly happiness over the "martyrdom" of marriage to St. John (Williams 20). In contrast, St. John's death as a missionary in India symbolizes the danger in denying oneself emotional pleasure (Johnson). Second, Jane learns to base her moral choices on her own judgment. She adopts a "relativistic or situational morality" that Rochester espouses when he tempts Jane to weigh out the ethical consequence of committing adultery over causing another human misery. Jane demonstrates her new sense of morality when she decides for herself not to marry the virtuous St. John (Benvenuto 48). Lastly, Jane's moral code places love and passion over religious duty. Her ideology contrasts with St. John's, who suppresses his romantic feelings towards pretty Rosamond Oliver because she does not fit the mold of a missionary's wife (Brontë 405-406). Jane, on the other hand, chooses to marry Rochester merely because she loves him (Benvenuto 48). Jane's development of individual moral standards is an expression of Brontë's cynicism towards customary Victorian morality (Benvenuto 48; Williams 21). Despite her perceived limitations by society, Charlotte Brontë made a powerful impact through her creation of an autonomous heroine who defies the social and religious norms of Victorian England. With Jane Eyre seen as a book that threatened the very foundations of society, Brontë established herself as a "progressive" woman of her time period (Lowes). The manifestation of her passionate spirit gave birth to a timeless work of literature with an indispensable message (Lowes). Jane Eyre inspires all individuals to voice their views, even if society does not yet embrace them. Adetunji 8 Works Cited Benvenuto, Richard. "The Child of Nature, the Child of Grace, and the Unresolved Conflict of Jane Eyre. " ELH 39, No. 4 (1972): 631-33. Rpt. in Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre. Ed. Harold Bloom. Broomall, PA: Chelsea, 1996. 45-8. Print. Brandon, Ruth. Governess: The Lives and Times of the Real Jane Eyres. New York: Walker, 2008. Print. Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. New York: Bantam, 2003. Print. Eagleton, Terry. Myths of Power: A Marxist Study of the Brontës (1975): 26-29. Rpt. In Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Ed. Harold Bloom. Broomall, PA: Chelsea, 1996. 54-58. Print. Glasser, Jonathan. “Questioning Evangelical Religion in Brontë and Dickens.” Victorian Web. 21 March 2003. Web. 15 Apr. 2010. <http://victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/ pickwick/glasser11.html>. Johnson, Nicholas. “The Tension between Reason and Passion in Jane Eyre.” Victorian Web. 2000. Web. 19 Apr. 2010. <http://victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/nj1.html>. "List of Characters." Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Ed. Harold Bloom. Broomall, PA: Chelsea, 1996. 21-23. Print. Lowes, Melissa. “Charlotte Brontë: A Modern Woman.” Victorian Web. 15 Feb. 2008. Web. 15 Apr. 2010. <http://victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/lowes1.html>. Mayer, Sonja. “Hey Teacher, Leave Those Readers Alone! Why a Governess’s Narrative in Jane Eyre Shocked Certain Victorians.” Victorian Web. 17 July 2006. Web. 19 Apr. 2010. <http://victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/mayer1.html>. Oates, Joyce Carol. Introduction. Jane Eyre. By Charlotte Brontë. New York: Bantam, Adetunji 9 2003. v–xvi. Print. Rigby, Elizabeth [Lady Eastlake]. "Rev. of Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Brontë." Quarterly Review 167 (1838): 172–74. Rpt. in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Ed. Harold Bloom. Broomall, PA: Chelsea, 1996. 28-30. Print. Schwingen, Mary. “Class Attitudes in the Westminster Review and Jane Eyre.” Victorian Web. May 1994. Web. 19 Apr. 2010. <http://victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/73cb class.html>. Williams, Tenley. “Thematic and Structural Analysis.” Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Ed. Harold Bloom. Broomall, PA: Chelsea, 1996. 10-21. Print.