Journal Article Reviews

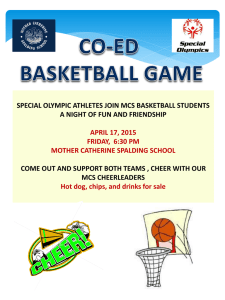

advertisement