Maidens, Wives, Widows: Women's Roles in the Chesapeake and

advertisement

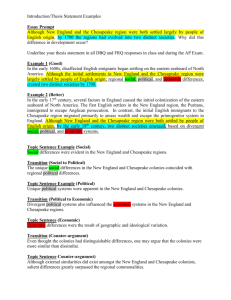

Maidens, Wives, Widows: Women’s Roles in the Chesapeake and New England Regions Melinda Allen Melinda Allen, a graduate student in History at Eastern Illinois, wrote this paper for Dr. Robert Desrochers’s graduate seminar on Early American History. In the spring of 2001, this paper received the Women’s Advocacy Council Graduate Writing Award. uring the 1960’s and 1970s, social history shined new light on the subject of the English colonies in America. The original thoughts about the colonies stemmed from the New England school, which argued the colonies’ culture developed in New England and was similar to that of England. Changing the predominant view of New England’s superiority, the Chesapeake school brought to the forefront the Chesapeake region’s similarities to England and their cultural dominance in the colonies. Yet, none of the studies really focused on women and compared their roles between the two places for differences and similarities. A second generation of students of colonial society from the late 1970s onwards, however, did so. This article attempts to synthesize the findings of these studies. Patriarchal ideas held by seventeenth and eighteenth century Europeans came to the New World with the settlers, yet these same settlers could not always enforce those ideas in the new environment. Between the Chesapeake Bay and New England regions, women’s roles in society were affected not only by the patriarchal ideals of society but also by the realities of life in the New World. Did these roles differ from their English origins? Did the roles differ even within the two regions? Do women’s roles help the validity of either school of thought? Women shared many of the same roles between the two regions. They delivered babies, raised children, and acted as helpmeets, a term used to describe a wife’s duty to help her husband with all facets of their life. Yet, within these very roles of wife and mother, women showed distinct differences in how they met the challenges of their lives. Demographics, for example the preponderance of men in the Chesapeake, initially influenced women’s roles in the two areas. Those who settled in the Chesapeake came to make money quickly. Eventually, the settlers began to form a permanent settlement in order to gain from producing the staple crop of tobacco, but tobacco requires a large amount of labor and laborers were scarce. Because settlers came to the region to make money, many did not have families that immigrated with them and the region developed a skewed sex ratio. When looking for indentured servants, settlers valued men more than women since men could increase the income of the land. The skewed sex ratio in Middlesex County was six men to one woman in the early years and three men to one woman by the 1680s. This allowed women more fluid roles socially. In addition to the lack of available labor, those living in the Chesapeake region suffered from the climate, which harbored diseases such as malaria, causing a high mortality rate. Husbands lost wives; wives lost husbands; children lost parents; parents lost children. Early deaths caused patriarchal ideals to weaken. After all, most marriages ended by death within 9 to 12 years. High mortality rates included a high degree of parental death. For example in Middlesex County, Virginia 48% of children lost at least one parent by their ninth birthday and by age 13 that figure rose to 60%. The surviving parent would often remarry creating an extended family, restoring some of the patriarchal authority lost. But, the breakdown of traditional families allowed women more power as “now-wives” because they represented a constant thread in the children’s lives. This pattern of early death led women to gain some power as widows. Plymouth, the first New England colony settled, and the Massachusetts Bay colonies both began with influxes of whole families, motivated by religion to build a shining example of a Christian community for the world. Because of the migration pattern, the New England colonies had sex ratios similar to English society. Thanks to the environment, the New England colonists lived longer lives than most Europeans. Low rates of mortality helped perpetuate the patriarchal system under which the Puritans functioned. Church leaders doubled as leaders in the colonies and kept citizens under strict moral control. Patriarchal authority developed with the Covenant as a way to keep order in the fledgling colony. The Covenant, an agreement by the males (occasionally women were allowed a vote within some churches) about the government, was then linked with patriarchal values in the family. In Massachusetts Bay, the Reverend John Cotton expressed the idea of a “mutual Covenant” that exists between “husband and wife in the family, Magistrates and subjects in the commonwealth, fellow citizens in the same cit[y].” People could be “free from naturall and compulsory engagements” and “can be united or combined together into one visible body.” Under the patriarchal system, the head of the family, the father, rules over everyone in his house. This person, sometimes called the family governor, would make all decisions dealing with the land and assets of the family. As in the Chesapeake region family in New England consisted of all those living under the same roof. For example in New Haven in 1656 all single persons “who live not in service, nor in any family relation, answering the mind of God in the fift[h] commandment”, that is, obey, could be considered a person to cause “inconvenience and disorder.” Those single persons should therefore live with appropriate family governors. In both regions male heads of households were carefully scrutinized D by political authority outside the home, neighbors would gossip about unruly children or abusive spouses to bring to light abusive masters or husbands. In Virginia, laws enforced the patriarchal authority by making sure that a male headed the household and that he would support his family by providing the appropriate food, clothing, shelter, religious and moral instruction. Yet, the government refrained from regulating private issues such as abuse. New England government on the other hand stepped in to regulate those very same private issues that the Virginia government shied away from. For example, the New Haven government would allow divorces for cruelty. They also regulated sexual behavior within the home, such as adultery issues. The family governor also would give consent to appropriate marriages for his children. The family governor was above all to be obeyed. Spouses should love each other, although that entailed the man striving to move beyond his wife’s inferiority in the spiritual, physical, and social realms. At the same time, the wife had to strive to reach the husband’s level of superiority without resentment of his power and authority. Women maintained absolute power in one aspect—childbirth. County courts received the names of fathers of illegitimate children from midwives. Midwives often were called in for their expertise on women’s bodies for a number of issues, such as whether a woman concealed a pregnancy. In the year 1664 in Maryland Elizabeth Greene, an indentured servant, stood trial for infanticide—a felony. The court called in Grace Parker, a midwife, to examine Greene and verify if Greene concealed a pregnancy. Grace Parker Examined saith That she was a stranger to the wench and did not see her above once all the time she was with Child and that she did search her breast and the wench denied she was with Child but there was milk in her breasts. And it was agoing away being hard and Curdled—And she desiring her to declare after she was delivered what she had done with her Child she said she had buried it in such a place but when they Came to search for it they Could find no such thing The testimony of Grace Parker swayed the court and Elizabeth Greene died for her actions. Midwives or matrons could be brought in to examine women convicted to die for pregnancy that prevented capital punishment. Under English Common Law, women were legally under their parents until married, and then their husbands assumed power over them. It is not until a wife became a widow that legally she existed and became a femme sole and outside of patriarchal authority within the home. The anonymous author of an English legal treatise expressed the following view: Why mourne you so, you that be widowes: Consider how long you have beene in subjection under the predominance of parents, of your husbands, now you be free in libertie, & free proprii juris at your owne Law. Although a widow could become head of the household in both regions, she could not encompass all the related roles. She could sue, make contracts, have a will written, be sued directly (not in her husband’s name), pay taxes, and became liable for her deceased husband’s debts. And yet, she could not vote, hold office, serve in the militia, or serve on juries. A widow legally gained a third of her husband’s property as a dower right; dower property was part of Common Law in England that was adopted in the colonies. Very few husbands left their wives less than the required third, but most made stipulations such as for life only, for widowhood, or for the minority of the children. The restrictions made remarriage more difficult because the widow would again lose power. Over half of all husbands left their wives more than the third for at least the minority of the children or during her widowhood. The empowerment occurred because husbands trusted their wives to see to the children’s care before strangers would. The key was keeping the inheritance together. Husbands might bequeath minors to stay with their wife, but specify that if she remarries and the husband abuses the children they would remove the children to a guardian. The empowerment actually came when the widow was named executrix of her husband’s estate. The age of the children made the difference in what a widow would gain. In the Chesapeake where husbands died young, children still in their minority often remained. Widows gained the most power when minor children were the only heirs. Her power lasted only until she remarried or the children came of age. If adult heirs were present, however, the heirs gained all, including instructions on how to maintain the widow. By trying to keep the land intact for heirs, the fathers bent the patriarchal ideas to allow women control only if the heirs were minors. If adult heirs were present, the fathers upheld patriarchal values by passing the land and the widows upkeep to them. As widows prepared to remarry, a few women signed prenuptial agreements with their future husbands. The agreements not only helped them to retain their own property, but also helped keep their children’s inheritance safe from their stepfathers. Prenuptial agreements might include such things as allowing a woman to make sales of her property or be able to make contracts in her own name, but most importantly they allowed women to keep land from previous marriages out of the hands of husbands who might abuse it. Admittedly, prenuptial agreements step outside the bounds of patriarchal authority, but few women used this option. Marital problems were often brought before neighbors and family before being brought to the courts. Parental consent to marry had to be obtained by not only children but also the indentured servants. According to the law, valid marriages were those “that had been consummated in sexual union and preceded by contract, either public or private, with witnesses or without, in the present tense or the future tense.” Yet in the early settlement period the Chesapeake authorities loosened their grip on the laws dealing with marriages in part due to a lack of sufficiently qualified clergy to hold the proper ceremony. Nearly one-half of all female immigrants went to the altar pregnant; one-fifth of the Creole population had bridal pregnancies. If parents lived long enough they tried to impose their wishes upon their children concerning marriages, especially if large amounts of property were involved. Consensual sex between men and single women resulted in the greatest number of criminal offenses, yet the crime of fornication and the related crime of illegitimacy differed between New England and the Chesapeake. In New England, fornication crimes were prosecuted at a greater rate than illegitimacy, but the opposite obtained in the Chesapeake. Young women’s legal status was part of the reason. New England’s young females consisted mainly of young women from free households contracted as servants. When these young women entered into a consensual sexual relationship with the man they intended to marry the resulting baby that appeared less than nine months after the wedding led to a charge of fornication. In the Chesapeake, this same group of young women consisted mainly of indentured servants with long-term legal contracts that forbade marriage without their master’s permission. Thus, the same consensual sexual relationship resulted in a bastard rather than a baby shortly after the wedding. The two regions differed in their view of which crime was worse. In the Chesapeake, a bastard created a financial burden on the community; fornication was viewed much more leniently. This can be seen in prosecutions of civil suits versus criminal suits, fornication versus adultery. The suing of the father for support appear, but not criminal charges. Acts that would have resulted in a crime and a sin in New England were forgiven after corrective steps taken. For example, a magistrate of Kent Island (Virginia) avoided prosecution by marrying the widow with whom he was accused of fathering a bastard. He did not even lose his office. In New Haven, couples could be charged with “lascivious carriage” or “filthy dalliance”; these charges occurred when an unbetrothed and unmarried couple participated in sexual acts that did not include proven intercourse. Often these charges resulted in whipping. The essential difference between the two areas rests on the definition of sin. Fornication was sinful in New England; financial burdens created the sin in the Chesapeake. Women formed relations both vertically through economic ties such as servant to mistress and horizontally through close friendships within the same class. Under this system, puritan communities also expected the women to behave a certain way, by using rules such as the rule of industry and the rule of charity. To be a good wife was to be a productive wife, and your neighbors would spread the tale if any wife were not behaving properly. The rule of industry also existed in the Chesapeake colonies as part of the ideals of duties as a wife; gossip by other wives spread the tale of those not following through on their duties. For example, Edy Hantinge in Norfolk County voiced disapproval of Mistress Hayward: Mathew Haywards wife did live as brave a life as any weoman in Virginia for she could lie abead every morning till her husband went a milkinge and came Back againe and washt the dishes and skimd the milk and then Mr Edward floide would come in and say come nieghboure will you walke and soe she went abroad and left the children cringe th[a]t hir husband was faine to come home and leafe his worke to quiett the children. This quotation brings to light more than just a woman neglecting her duties does. First, her husband does the milking and dishes both considered women’s work. Second, she walks about with neighbor men, which implies illicit relations. Third, while she walked her husband had to leave his work in order to settle the children, this again should be the wife’s job. A woman known for cruelty to servants held the indenture of the speaker. Perhaps the statement indicated a desire for the life that Mistress Hayward led, or a longing for better treatment in her own life. In any case, Edy Hantinge apologized for the comments after Mistress Hayward brought her to court. The rule of charity insisted that the wealthier people should help the poorer people and gossip again acted as a tool to enforce the rule. For example a servant, Sarah Roper, carried off over ten pounds of goods from her mistress, but was not prosecuted by her mistress until she called her “an old Jew and hobling Joane” implying that the mistress did not give charity as she should. The slander caused the case to be brought before the judges. Women had power through gossip in both regions. Gossip allowed moral and legal issues such as fornication, illegitimacy, theft, and abuse to become known and corrected. Kathleen Brown states “women’s gossip acted as a form of social control that competed with more formal legal institutions and perpetuated gender-specific standards for reputation.” A woman’s good name related to her sexual reputation. Defamation suits represented the primary method a woman used against women of the same status for slander. Usually a woman was called a whore or other related terms such as “hoore, theife, and Toade,” “pissa bedd jade,” or, “you slut.” These epithets followed a woman around for years later, even if she fought against the slanderers. Hannah Marsh Fuller Finch provides such a case. Finch’s ordeal began on her journey to the colonies; she came as a servant in New Haven and immediately sued Mr. Francis Brewster. Supposedly, Brewster called Finch a “Billingsgate slutt” while on board the ship. The allegation included the notion that Finch was not only a woman of loose moral character but also claimed that she was condemned as a scold, a shrew. Finch won this case when Brewster admitted he had no proof, yet the story would not die. Four years later the magistrate’s wife accused Finch of misconduct and began gossip about Finch and other men. Again, Finch was found not guilty. Two years later, the rumors surfaced again only to die after a forced apology to keep the case from court. Thirteen years later, the rumor became known again but with reference to Finch’s daughter. This series of events shows just how much power a single rumor held within a community. Hannah Finch had moved up in society from servant girl to a respectable member of society. Each one of the entanglements with the rumors developed in part over a power struggle between Finch and her accusers. The first accusations came from a man who claimed actions for which he had no proof. The second, a magistrate’s wife, might have felt that Finch’s actions too bold for a respectable wife. The last comment came from an argument over her daughter’s behavior, which alleged the daughter followed her mother’s example. Finch’s bold behavior led to a rumor resurfacing every time a problem within the community network developed. Religion varied greatly in the early years of settlement. The Chesapeake lacked a unifying religion; people practiced Catholicism, Anglicanism, Quakerism, and other Christian religions. New England consisted primarily of Puritans. The puritan religion provided some authority for women yet simultaneously caused women to fight for more power. Women could not be ministers nor did they sign the covenant to create the congregation. Yet women could attain sainthood and did to a greater extent then men, causing membership at younger ages and in larger numbers among women. As Ulrich asserts, “[r]elying upon private power within their own families, women promoted the establishment of religion in outlying areas of older towns; using their influence within the village network as well as with their husbands, women served as guardians of ministerial reputation.” As more women entered the church, they gained power. For example, women often led the battle for new churches within walking distance. Women taught their children religion. Ministers carefully cultivated the support of women by avoiding negative gossip both in and out of church. The minister that alienated his women followers faced challenges staying minister within that church. Puritan leaders confronted captivity surprisingly frequently in their families and communities. Age and gender were the keys to a captive’s fate. Men were more likely to escape or die resisting captivity. Women adapted and were more likely to remain with their captors. Historians argue a variety of reasons for women remaining. Marriage played an essential role. Married women rarely stayed, except in cases of extreme circumstance. However, young ladies expected to leave their homes and possibly their communities when they married, to also lose their nationality and language was not expected but women adapted. If they married a Frenchman, by law they became French thus gaining equal status to that they would have had in New England. Religion offered women another reason to remain; Puritanism only gives women one choice for fulfillment— marriage. Catholics have a second choice they can become nuns. Nuns provided an extensive female network that supported captured young ladies, and sought to teach and convert captives. Some women fought against the patriarchal constraints of Puritanism. Women such as Anne Hutchinson battled for the right to preach. Mary Dyer lost her life for the Quaker cause. These women disrupted the authority in the colonies. Anne Hutchinson threatened the Puritan patriarchal structure. Her home was the gathering place for women’s meetings. Women were denied the right to attend any weekday sermon or public lecture; there were female meetings before Anne moved to the colonies but she expanded them and the authorities saw this as a breeding ground for dissident proselytizing. Whether or not she was an antinomian and believed that salvation lay with a direct relationship to God, does not matter. The problem lay in what Governor John Winthrop believed she preached. Her trials reveal a view that she challenged the family order, morality, and the patriarchal system. These trial records come from the viewpoint of Winthrop, so bias already exists. For example, an exchange takes place where Winthrop leads Anne to try to gain an admittance of breaking the fifth commandment, the commandment that patriarchal authorities use to support their ideology. Mary Dyer’s case shows just how much power women held within their realm. Dyer traveled to the colonies to protest the persecution of Quakers. She even went so far as to write a letter to the general court of Massachusetts protesting the persecution. Mary Dyer delivered a stillborn, deformed child in October of 1637. The midwife, Jane Hawkins, Anne Hutchinson, and one other woman were present during the birth. The women kept the birth a secret from the government for over five months. When Dyer left church with Hutchinson after her excommunication, Winthrop asked who Dyer was. The reply mentioned the monstrous birth. When Winthrop investigated the information, he found that a community of women knew about the rumor for months. Winthrop understood that women discussed events like the birth with other women, but not with men. The issue of her monstrous birth fell to the sidelines when she challenged patriarchal authority in defense of the Quakers. Unlike Anne Hutchinson, Mary Dyer did not back down graciously or leave the colony but became a martyr to the Quakers in 1660. As the seventeenth-century ended, the patriarchal system tightened its grip on the Chesapeake colonies. The mortality rates evened out; marriages lasted longer. Widows rarely gained power over their husband’s estates. Further immigration from England helped strengthen beliefs in the Common Law of England and patriarchal ideals. Fathers survived to supervise children, helping to reduce bridal pregnancy. Wives lost power gained in the courts as husbands reasserted their dominance. Yet, dominance did not mean wives lost all power. They gained power by two laws, which required justices to question wives separately and get their agreement before the husband could sell the dower property. Wives also gained a stronger legal position for protection against abuse and abandonment. In New England, the women lost power as well. The healthy climate no longer permitted longer lives and life expectancy evened out with other colonies. Women lost the role of executrix. The power of a woman’s word no longer held credibility in courts. Divorces became harder to obtain in cases of cruelty. Adultery remained defined by a married woman having extramarital intercourse. At the turn of the eighteenth-century, the colonies began to converge. New England lost its healthful advantage, gained a more disperse population as younger sons moved to gain more land, and lost control religiously with an influx of new settlers. The Chesapeake settlers grew more accustomed to the climate and built stronger social institutions. Yet throughout, women’s roles lost stature. The role of widows became less important as men began to live longer. The role of women in controlling social morality dropped as the effects of events such as the Salem witch trials pointed out the fallacies in believing everything that is uttered from upstanding groups. Yet women maintained important roles such as child rearing and they maintained importance in the church. Although formal power of women weakened, informal power grew stronger. Women’s power became more similar in the two regions by the end of the seventeenth-century. Neither school of thought really presents a strong case for the prevalence of their region. Both regions had gossips, sexual crimes, death, and widows. Women continued to hold sway over childbirth, but the ideal of the genteel wife emerged as more imported goods found their way into the colonies. The freedom women gained in both regions due to the differences in the New World began to subside as the colonies developed stronger economically. Where women are concerned, the school of thought needs to be modified into a blend of the Chesapeake and New England schools. Both regions contribute to the role of women in the years to follow, and both set up precedents for women to gain power in later years.