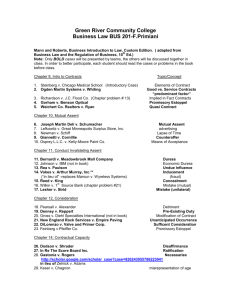

MAKING SENSE OF CLICKWRAP, BROWSEWRAP AND

advertisement