Midwest Home Fruit - Purdue Agriculture

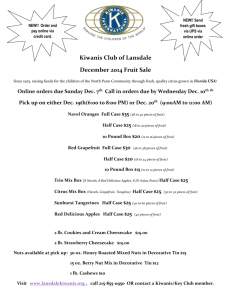

advertisement