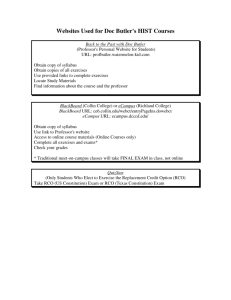

Ecampus Task Force Report

advertisement