big history teaching guide

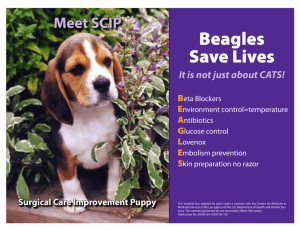

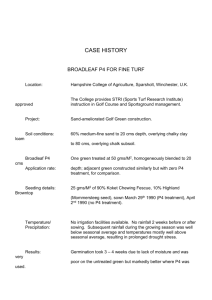

advertisement