A Preliminary Investigation into the Coaching Behaviours of English

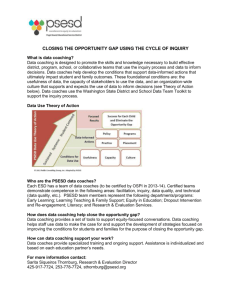

advertisement