Conducting Valuable Preliminary Investigations

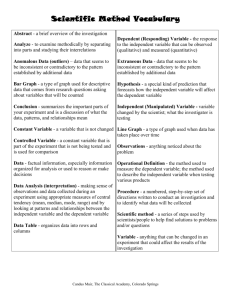

advertisement

GMP Conducting Valuable Preliminary Investigations Peter Weichel Why do projects fail? What can be done to prevent it? This article presents a practical concept and corresponding methodology for how to obtain relevant data and information prior to more detailed project conceptualization and project start. Obtaining relevant data and information before a project start is essential to all project startups and will increase the likelihood of successful project completion. INTRODUCTION Running projects is common practice within many businesses and industries. Some companies have developed a formal project office that provides a final project model and project handbook, whereas other companies have a more informal structure for running projects. A generic and classic high-level model for project lifecycles contains phases like conceptualization, planning, testing, implementation, and closure (1). This model describes what will happen when the decision to start a project has been taken. But before a project has been decided, there is a phase—sometimes called the pre-analysis phase—that should be completed. This pre-analysis phase is important to all projects, but is not covered well in the common literature and is not always used in projects. It is a vital phase, because the lack of such an investigation can influence the future project. The purpose of this article is to outline how a preanalysis can be performed. In this article the pre-analysis is called preliminary investigation. The article tries to provide a generic concept for conducting preliminary investigations. It is based on the author’s personal experience with managing projects in general. 74 Journal of GXP Compliance WHY PROJECTS FAIL Many projects, especially IT projects, tend to fail when measured on parameters like budget, plan, quality, and the resulting system. A famous research study conducted in 1995 in the United States by the Standish Group surveying companies in different industries found that, on average, only 16.2% of software projects are completed on time, within budget, and with all features and functionalities as initially specified (2). In this study the Standish Group also concluded that the following are the main reasons why software projects are challenged: • Lack of user input • Incomplete requirements and specifications • Changing requirements and specifications • Lack of executive support • Technology incompetence • Lack of resources • Unrealistic expectations • Unclear objectives • Unrealistic time frames • New technology • Other. More recent studies have confirmed the low project success rate even though it has improved over the past years. With this in mind, it makes sense to conduct a short preliminary investigation at an early stage and before a project is started. Preliminary investigations can be used to prepare users at an early stage for potential future changes and thereby help anchor an upcoming project. Ultimately, the preliminary investigation can reveal that a planned/requested project is not actually needed or will not add value to the business, thereby saving time and resources. Peter Weichel S2: Implement new system/processes/technology S0: Current situation S1: Redesign current system/processes/technology Figure 1: Field in focus of the preliminary investigation. PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS Preliminary investigations should be performed before project conceptualization and project start. They should be used to retrieve important data and information that will later be used in project conceptualization (e.g., when writing the business case for the project). Basically, the preliminary investigation looks at situations S0, S1, and S2 and their relations, as shown in Figure 1. Conducting a preliminary investigation should not be a long or major task, as this could de-motivate or actually prevent projects from starting. The preliminary investigation should by definition be a quick and initial survey of situations S0, S1, and S2 before a more detailed investigation is started. A period of one to three months is recommended, depending on the project and the business processes in focus. Investigations longer than three months should not be classified as preliminary investigations. Who should conduct the preliminary investigation? It is recommended that one person be put in charge of the investigation. If needed this could be supplemented with one to three persons functioning as consultants, specialists, or reviewers in a reference group. The important thing here is to avoid a large formal project group, as this could prevent a quick investigation and instead turn the preliminary investigation into a longterm project itself. A preliminary investigation should involve the elements, methodologies, and output shown in Figure 2. Other items can be included as well, but the most important ones are outlined in this article. It is important to remember that a preliminary investigation is not a scientific study and should not try to give definite answers for every issue. The final product of the preliminary investigation should be a short report. THE ELEMENTS The elements of the preliminary investigation include the scope analysis, the problem survey, and the benefit analysis. The purpose of these elements is to get a clear understanding of the basis and objective of a future project before the project work is actually started. Knowing these three elements (scope, problems, and benefits) is essential for all project startups. The scope analysis can be done by simply asking the following questions: • Who are the potential users? • Which departments or business areas could be involved? • What are the business processes (i.e., high-level description, not detailed)? • Are records or documents generated? • Do regulatory requirements or standards apply (e.g., GLP, GCP, or GMP)? • What kind of technology is used? The problem survey simply consists of the following: • Description of the major problems existing (userfriendly description, not technical) • Categorization of the types of problems (organizational, technology, human resource problem, etc.). Do not try to offer solutions, but simply describe problems. Winter 2009 Volume 13 Number 1 75 GMP Preliminary investigation: Elements: Methodologies: Output: • Scope analysis (S1, S2) • User interview • Preliminary vision (S1, S2) • Problem survey (S0) • Data analysis • Draft scope (S2) • Benefit analysis (S1, S2) • Questionnaire • List of identified problems (S0) • List of identified improvements (S1) • List of identified benefits (S1, S2) • List of key-stake holders (S0, S1, S2) • Preliminary URS (S2) • Initial economic assessment (S2) Figure 2: Elements, methodologies, and output of a preliminary investigation. As with the problem survey, the benefit analysis simply consists of the following: • Description of the benefits (user-friendly description, not technical) • Classification of the benefits as quantitative benefits and non-quantitative benefits. How is data and information obtained as input for the scope definition, the problem survey, and the benefit analysis? THE METHODOLOGIES The user interview, the data analysis, and the questionnaire can be used together, individually, or in combination to obtain data and information. The person in charge of the preliminary investigation should choose the methods that are best suited to the situation. The user interview is done by interviewing relevant users in the business and technology areas. Do not try to interview every employee in the company, but find a representative group. An agenda should be issued first, and questions must be prepared beforehand (see Table I). The types of questions presented in Table I are active questions (also called “open questions”) in the sense that they require the interviewees to actively reflect on the situations and not just answer yes or no. Interviewing users 76 Journal of GXP Compliance • Initial cost-benefit analysis (S1, S2) • Current conclusion/recommendation could also be combined with a demonstration of the business activities or processes in action. Other parties than the real users could also be interviewed. Company visits or visits by technology vendors could provide important data and input (e.g., key figures indicating the price level of the technology on the market). At this stage the purpose should only be to obtain initial economic assessments giving a hint of the price level of the technology on the market. No price negotiations or tender process should be started at this stage, because it is too comprehensive at this stage and is done in later project phases. Data analysis is a broad term and somehow reflects the fact that it involves analyzing data from the business processes. If, for example, the system currently in place uses an Access database for controlling documents (e.g., a complaint database) the data analysis could simply be to retrieve data from the system that answer the following questions: • What is the lead time for records generated in the system? • How many records have been generated over the past years? • Which users/departments have generated most records over the past 24 months? Peter Weichel In most electronic systems, this data can easily by retrieved by simple queries in the system, either directly from the user interface or, alternatively, from the system administrator using an appropriate query language behind the database application (e.g., SQL or similar). The important thing here is that the person in charge of the preliminary investigation outlines the relevant questions. Using questionnaires can be more difficult, because the perception of written questions can be different from person to person. Basically, questionnaires can be issued on paper (i.e., P-surveys) or on electronic media, for example the Internet (i.e., E-surveys). Questionnaires should be tested before they are issued. Professional courses are provided on how to prepare good and useful questionnaires. Several courses can be found on the Internet that can help in avoiding the most common pitfalls when designing and writing questionnaires. The advantage of using questionnaires is that people participating can return their answers at their convenience. On the other hand, answering questionnaires can be time consuming for people, and the number of respondents can sometimes be low and, therefore, not representative. Here it is important that the person in charge of the preliminary investigation actually asks what the purpose and objective of issuing a questionnaire is. What will be obtained that cannot be obtained by a user interview? The person in charge of the preliminary investigation should ask the following questions: • What is the purpose and objective of the questionnaire? • What data/information do we want from the respondents? • What do we know before issuing the questionnaire? • How will answers be analyzed, processed, and presented? All together, the user interviews, the data analysis, and the questionnaire will collect important data and information that will serve as input to the scope definition, the problem list, the list of identified benefits, the potential key stakeholders, etc. This information is analyzed and processed by the person in charge of the TABLE I: Type of questions used in the user interview. 1. What are the three most critical issues with the current system? 2. What are the three most important reasons/benefits for changing to a new system? 3. What are the most important redesigns that can be made to improve the current system? 4. Who are the most important user(s) of the current system? preliminary investigation and presented in the preliminary investigative report. THE OUTPUT The processed results are collated and presented in short form in the preliminary investigative report. The results can be displayed in attachments to the report (e.g., as lists or in bullet form). A fictional example of a scope definition is provided in Table II. A fictional example of problems identified during the preliminary investigation is provided in Table III. A good understanding of the problem area ensures that problems from the legacy world will not be transferred to the new or redesigned system/process/technology when writing the final user requirement specification (URS) in later project phases. Not all the items listed in Figure 2 need to be output of the preliminary investigation. This depends on the specific situation. The important thing is that the preliminary investigation by definition does not offer definite or scientific answers to every issue. Interim results could be used, as well. HOW IS THE PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION USED? The final product is the preliminary investigative report. It is valuable to the upcoming project and serves as a baseline or starting point of knowledge. The report provides, for example, valuable and useful information when defining the vision in more detail and writing the business case of a coming project. It can also give initial economic assessments of a future project or a specific technology on the market before a real tender process is initiated. The report does not offer final answers to all issues, but functions as a tool to help a project group deWinter 2009 Volume 13 Number 1 77 GMP TABLE II: Example of a scope definition attached to the preliminary investigative report. Our preliminary investigation has summarised a draft scope for a future EDMS system: • The system should apply to all compliance users in the company (i.e., users in Production, R&D and QA/QC) • The number of future users has been calculated to approximately 500 users • T he system should manage quality manual (company policies) and SOPs • The number of documents have been estimated to 5000 • The system must be electronic and should be provided by a professional vendor • 21 CFR Part 11 and EudraLex Annex 11 apply. TABLE III: Example of a list of problems attached to the preliminary investigative report. Our preliminary investigation has revealed the following problems with the current document management systems: I: Many users find that our current document management system has too many document types. Clear definitions of each document type are also missing. In particular, the difference between company guidelines and SOPs is not clear for users [organisational problem]. II: The search engine in our current system does not allow for full-text searches. Many users complain that it takes time to find the right documents [technical problem]. III: Each business area in the company has its own document management system, making it difficult to retrieve and read documents from related areas. It has been found that the company currently has six document management systems in place [organisational problem]. IV: Many users find that the lead time from document drafting to document approval is very long. Users request a shorter or quicker document process. Our investigation shows that the average lead time is 42 days and is primarily taken up by the review phase [technical problem]. 78 Journal of GXP Compliance termine which direction the more detailed work should take. The preliminary investigative report should contain a conclusion or recommendation with regard to which direction the work in the future project should go. In case a decision has been taken during the preliminary investigation the output could instead be written directly as a Project Charter for a future project. CONCLUSION This article has been written with the objective of providing an example of how a preliminary investigation can be conducted. The example is presented in generic form, independent from a specific project in mind. Other approaches for performing preliminary investigations can be used. The important thing is that the person in charge of the investigation chooses the approach and methods most appropriate for the specific situation. REFERENCES 1. H. Kerzner, Project Management—A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2. The Standish Group International, Inc, The Standish Group Chaos Report, 1995. GXP ARTICLE ACRONYM LISTING CFR EDMS GCP GLP GMP QA QC R&D SOP URS Code of Federal Regulation Electronic Document Management System Good Clinical Practice Good Laboratory Practice Good Manufacturing Practice Quality Assurance Quality Control Research & Development Standard Operating Procedure User Requirement Specification ABOUT THE AUTHOR Peter Weichel holds an M.S. degree from University of Southern Denmark. He is IPMA certified as a Project Management Associate and works as a project manager in the pharmaceutical industry. Peter can be reached at peterweichel@hotmail.com.