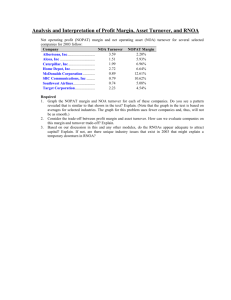

Do Investors Overvalue Firms with Bloated Balance Sheets

advertisement