Floaters and flashes: the signs of acute posterior

advertisement

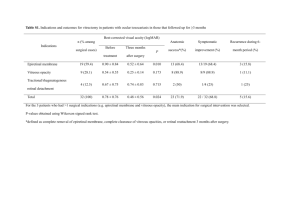

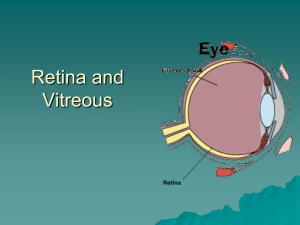

Ophthalmology 29 Floaters and flashes: the signs of acute posterior vitreous detachment Acute posterior vitreous detachment is a common cause of unilateral floaters and flashing lights. These visual experiences are frightening for the patient, and in an eye examination the physical findings are usually few and often subtle. It is a condition that frequently occurs in the older population. Drs Chintan Sanghvi, Sarita Bhat and Jason Raw discuss its pathophysiology and management. DR CHINTAN SANGHVI is a specialist registrar in Ophthalmology and DR SARITA BHAT is a specialist registrar in Geriatric/General Medicine at the Northwest Deanery; DR JASON RAW is a consultant geriatrician at Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust, Fairfield General Hospital P osterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is an age-related degeneration of the vitreous jelly commonly found in older people1 and in an autopsy study, was found in 63 per cent of patients older than 70 2 . Studies have demonstrated a clear increase in prevalence of PVD with age and certain studies have reported a prevalence rate varying from 57 per cent to 86 per cent in the ninth decade3,4. However, one should not presume PVD is inevitable with ageing as in a significant proportion of people the vitreous remains attached. It is found at an earlier age in myopic eyes as they are associated with increased liquefaction of the vitreous body. The relationship between the degree of myopia and the age of onset appears to be directly related as the higher the degree of myopia, the earlier is the onset of PVD5. The normal ageing process the vitreous gel undergoes to result in a PVD is accelerated by trauma, cataract or intraocular surgery, YAG capsulotomy, intraocular inflammation, diabetes, vitreous haemorrhage and certain hereditary conditions6. A recent study has postulated that the high oestrogen levels seen in premenopausal women may protect against PVD and that hormonal changes in menopause may lead to changes in the vitreous, predisposing PVD7. Pathophysiology The vitreous is a clear mass that makes up 80 per Figure 1: Slit lamp image of complete Weiss ring suspended in the vitreous in front of the optic disc cent of the volume of the globe and occupies the posterior cavity of the eye between the lens and retina. It has the physical and chemical properties of a hydrogel, being composed mostly of water, and its molecular structure is made up of collagen and sodium hyaluronate. These elements interact in a manner that keeps the vitreous in a stable gel state8. Ageing is accompanied by the formation of liquid fi lled pockets in the gel. These enlarge and become confluent. Some of these eyes develop a hole in the degenerated cortical vitreous that september 2007 / midlife and beyond / geriatric medicine 30 Ophthalmology overlies the retina. The collected fluid in the cavities empties into the space between the vitreous and the retina forcibly detaches the posterior vitreous surface from the neural retina. The remaining solid vitreous gel collapses creating disturbing symptoms in the form of suddenly appearing floaters and the accompanying vitreous traction on the retina produces the sensation of flashing lights also called photopsiae9. In normal eyes the peripheral vitreous is loosely attached to the innermost lining of the retina called the internal limiting membrane (ILM) and strong adhesions only occur at the vitreous base and around the optic disc. The detached vitreous attachment to the optic disc typically appears as a donut-shaped opacity in the vitreous and is known as a Weiss ring (see Figure 1). The collapse of the vitreous gel in a PVD in these eyes is not associated with untoward sequelae. In eyes with areas of certain types of peripheral retinal degenerations, abnormally strong adhesions may occur between the vitreous and the retina and during PVD vitreous traction on these adherent areas may result in a retinal tear. If unchecked by prophylactic retinal laser treatment, this may progress to a full retinal detachment, ie a break of the neural retina from the retinal pigment epithelium10. Signs and symptoms PVD is heralded by a sudden onset of flashing lights, usually oriented vertically in the temporal field of vision, and one or more new floaters. The process is painless. The luminous flashes are exacerbated by rapid eye movement. Patients may experience one large floater, which can be distracting when it comes in their line of sight — or may describe spiders, fl ies, cobwebs or rings moving around in their visual field. Movement of the eye stirs the vitreous so that the suspended debris move correspondingly. Vitreous floaters are most apparent when there is a uniform background illumination, such as a white wall. Floaters typically become less bothersome over a period of weeks to months as they settle below the line of sight or the brain adapts to them. Numerous floaters or decreased vision accompanying the aforementioned symptoms of an uncomplicated PVD are indicative of a more serious problem. Numerous or ‘too many to count’ floaters suggest red blood cells from an avulsed retinal blood vessel or pigment granules from the retinal pigment epithelium are present in the geriatric medicine / midlife and beyond / september 2007 vitreous. A sudden decrease of vision along with the flashes and floaters, or a veil or curtain that obstructs all or part of the vision is indicative of a retinal detachment. These symptoms may not only occur concurrently but can manifest at any time after the onset of PVD. Thus all patients should be encouraged to seek urgent medical attention if they develop these problems after an uncomplicated PVD. Complications Symptoms that may indicate a more serious problem include: > Sudden decrease of vision along with flashes and floaters; > A veil or curtain that obstructs all or part of the vision; > A sudden increase in the number of floaters. Although the majority of patients with acute PVD develop no complications, sight threatening sequelae, such as retinal breaks and vitreous or retinal haemorrhages, may occur11. Retinal detachment (RD) can result from retinal breaks caused by PVD; 10–15 per cent of all patients with acute symptomatic PVD have at least one retinal break. The incidence of breaks is higher in myopic eyes as they have pathologically thin retinal tissue and a greater occurrence of peripheral retinal degeneration and diffuse chorioretinal atrophy. In patients with acute PVD and vitreous haemorrhage the incidence of retinal tears increases to 70 per cent12 . Management Clinical history apart from age should include onset, myopia (monocular or binocular), recent trauma or cataract surgery. Apart from the history of presenting symptoms and past ophthalmic history, it is also important to note the past medical history of the patient. Various systemic conditions may predispose the patient to vitreous haemorrhage (eg, diabetes mellitus, sickle cell disease and vasculitis) or retinal breaks (eg, Stickler syndrome). There are no medications or eye drops to make the floaters disappear. Patients with unilateral flashes and floaters require prompt referral to an ophthalmologist and a complete ocular assessment that includes measurement of visual acuity, pupillary examination, confrontation fields, slit lamp examination of the anterior segment and vitreous, and dilated fundus examination using an indirect ophthalmoscope with scleral indentation. Ophthalmology 31 Key points References • Two factors that have been found to be important in determining the onset of PVD in a healthy person include age and refractive error. 1. Hayreh SS, Jonas B. Posterior vitreous detachment: clinical correlations. Ophthalmologica 2004; 218(5): 333–43 2. Foos RY, Wheeler NC. Vitreoretinal juncture; Snnchisis senilis and posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmology 1982; 89: 1502 3. Akiba J. Prevalence of posterior vitreous detachment in high myopia. Ophthalmology 1993; 100: 1384–8 4. Weber-Krause B, Eckardt C. [Incidence of posterior vitreous detachment in the elderly]. Ophthalmologe 1997; 94: 619–23 5. Yonemoto J, Ideta H, Sasaki K, et al. The age of onset of posterior vitreous detachment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1994; 232: 67–70 6. Jakobiec A. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology W. B. Saunders Company Philadelphia Chapter 97 Retinal Detachment: 1084–89 7. Chuo JY, Lee TY, Hollands H, et al. Risk factors for posterior vitreous detachment: a case- • PVD is not an inevitable part of the ageing process. • The signs and symptoms include sudden onset of floaters and flashing lights in the peripheral vision, and the process is painless. • Complications include retinal breaks, retinal tears, retinal detachment, vitreous haemorrhage and visual loss. Referral to an ophthalmologist is therefore imperative. • No medications and/or eye drops can treat floaters and, although annoying, they usually tend to settle. However, patient education regarding the potential complications cannot be stressed enough. Scleral indentation enhances visualisation of the peripheral retina. It involves the use of an indentor, which is used to exert gentle pressure on the globe through the eyelids. This creates a mound of peripheral retina that can be observed by indirect ophthalmoscopy. When properly done, it is well tolerated by most patients. A prompt and conscientious vitreoretinal examination of patients who experience flashes and floaters, combined with expeditious treatment of any retinal tears, provides the most effective known means of preventing retinal detachment secondary to a retinal break13. Counselling Most patients need reassurance and an explanation regarding the nature of the floaters. Floaters are annoying and can interfere with day-to-day activities but are essentially benign and should settle after a few months. However, awareness of potential complications is a must and therefore all patients should be educated about the symptoms of PVD and retinal detachment, and instructed to seek ophthalmic evaluation promptly if they have a significant increase in floaters, loss of visual field or decrease in visual acuity. Patients also need to know it is an age-related process that is very likely to occur in the other eye as well and the fellow eye needs examination as well when it occurs. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. control study. Am J Ophthalmolog 2006. Dec; 142(6): 931–7. Adler Physiology of the eye clinical Application Eighth edition Kanski Clinical Ophthalmology fourth edition Burtterworth Heinemann Chapter 9 Retinal Detachment: 354–94 Kanski, Milewski, Damato, Tanner Diseases of the ocular fundus Elsevier Mosby Edinburgh Chapter 6 Retinal detachment: 220–80 Novak MA, Welch RB. Complications of acute symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmology 1984; 97(3): 308–14 Jaffe N. Complications of acute posterior vitreous detachment.Arch of Ophthalmology 1968; 79: 568 Byer NE. Natural history of posterior vitreous detachment with early management as the premier line of defence against retinal detachment. Ophthalmology 1994; 101(9): 1503–13 Conclusion Posterior vitreous detachment is a common occurrence among the older population and in the majority of patients does not lead to sightthreatening complications. It represents a significant event to the eye with respect to the risk of development of retinal tears. In order to identify and appropriately treat the small number of patients whose PVD may be complicated by a retinal tear or a vitreous haemorrhage, all patients presenting with symptoms of unilateral flashing lights and floaters should be referred for a prompt ophthalmic evaluation as it may allow timely intervention of PVD-related complications before vision loss can occur. Conflict of interest: none declared. Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the Clinical Imaging Department at the Manchester Royal Eye Hospital for their help in obtaining the image of a posterior vitreous detachment. september 2007 / midlife and beyond / geriatric medicine