Sociological Theory and Social Control

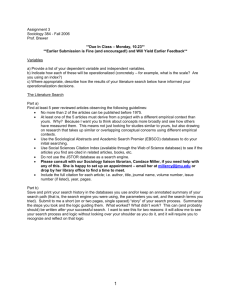

advertisement