A social organization theory of action and change.

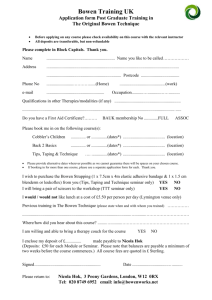

advertisement