Straight Documentary Photography and Surrealism

advertisement

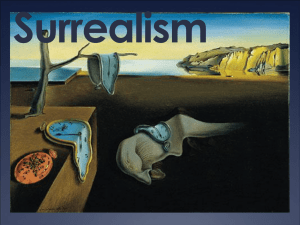

ALEXANDRO “ALEX” LEME UALR – Donaghey Scholars Program NHCH 2013 Student Interdisciplinary Research Submission Title: “Straight Documentary Photography and Surrealism: A Dialectical Resolution” The origin of Surrealism can be traced back to early 20th century Paris, where it began as a literary movement. Surrealist writers sought to free the subconscious from any logical or mediated responses by experimenting with the concept of automatism or automatic writing. Surrealism achieved its first victories precisely in the realm of poetry. But it was in 1924, with the publication of the Manifeste du Surréalisme by the poet André Breton, that the Surrealist movement was officially launched. Surrealism would later become an international current of thought that often instigated both positive and negative intellectual and political responses. Surrealists were influenced by psychological theories and dream studies developed by Sigmund Freud along with political ideologies proposed by Karl Marx in the 19th century. Based on Freudian methods of free association, Surrealist poetry and prose explored the private world of the mind, traditionally restricted by reason and societal limitations, to produce surprising, unexpected imagery. André Breton, in his Manifeste du Surréalisme, describes Surrealism as “the psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought.”1 The Surrealist movement also finds its ancestry, as well as its disregard for the traditional concepts of what art is supposed to be in Dadaism. Initially, Surrealist writers dismissed the idea that Surrealism could be represented in the visual arts. They believed that the deliberate and laborious natures of painting, sculpting, and 1 André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), 26. 1 of 17 drawing were in opposition to the spontaneity and uninhibited expression inherent within Surrealist concepts. Furthermore, the idea of incorporating Surrealism into photography, which was viewed as merely an effort to copy reality, seemed outrageous. Fascination with its effects, awareness of its potential to revolutionize the visual arts and distrust of its mimetic nature summarizes Surrealist attitudes towards photography in earlier texts. This belief, nonetheless, was changed by Man Ray’s portrait of Marquise Casati, ca. 1922 (figure 1). In this photograph, Man Ray accidentally blurred the subject’s face, thus creating both a dream-like effect and the illusion that the woman had more than two eyes. A whole new set of possibilities within photography had just unveiled itself. Even though by chance, the incident was enough to show that reality could indeed be manipulated through photography. Consequently, photography’s presumed eccentricity to Surrealist thought and practice had to be reconsidered.2 Surrealism in photography was hitherto performed mainly by the actual manipulation of the images through techniques such as photomontage, photogram, multiple exposure, solarization, and glass negative. As diverse as these techniques may have been, there is one form that merits further development: the Surrealist, but straight, documentary photography. What is more, numerous studies have already scrutinized several aspects of the staged and manipulated photography produced within Surrealism. Little, however, has been explored surrounding ideas of documentary photography. For this reason, this paper endeavors to disassemble the barriers between “the real and the surreal,” ultimately striving towards their dialectical resolution. Primarily, this task entails the investigation of photographs published in Surrealist books and magazines. Underpinning this study is the premise that a single photograph may shift meaning as it moves from the place where it has been taken to the place where it is published or 2 Rosalind Krauss, “The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism,” October 19 (Winter, 1981): 3-34. 2 of 17 viewed. It is therefore assumed that the articulation of the work within the context of its reception can unveil its Surrealist dimension. Secondly, perhaps less factual but equally important, it is the exercise of probing into what the Surrealists, chiefly André Breton, might have said about photography and, when hard evidence lacks, how one might read an image through Surrealist lenses. This effort proves especially relevant with works that do not come from within the traditional ideas of the Surrealist movement itself, but can be placed next to and in juxtaposition with Surrealism. Nevertheless, if one is to oppose the latter approach, it should suffice to understand that the Surrealists themselves were “guilty” of re-contextualizing, often by re-titling paintings in order to suggest alternative [Surreal] readings of the works. As a matter of fact, it is known that de Chirico complained about the Surrealist habits of changing the titles of his paintings when he once stated: “it twisted the meaning of his work and set the stage for an ambiguity that is dangerous for the market.”3 However, any Surrealist theorization of photography is fragmentary and elusive, and the reading of it must be consciously retrospective. With that in mind, this essay intends to show that Surrealist documentary photography can subvert the very ‘straightness’ of the medium and its apparent realism in order to create the surreal. In fact it claims that this type of documentary photography can be more disruptive of conventional norms than the contrivances of darkroom manipulation. To forge this argument and narrow the scope of this research project, I chose to focus on works made in Paris in the years between the two World Wars. In the 1920s and 1930s, this genre of documentary photography largely took place in and around city settings, where the banal and the extraordinary coexist on a daily basis. Across Paris, for example, photographers identified several privileged places, especially resonant for 3 M. Guerrisi, La nueva pittura: Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, Derain, De Chirico, Modigliani (Torino: Dell-Erma, 1932), 64-65. 3 of 17 personal or cultural reasons, which had always been an important facet of Surrealism. In his first collection of essays Les Pas Perdus in 1923, Breton wrote: “The street, which I believed could furnish my life with its surprising detours; the street, with its cares and its glances, was my true element: there I could test like nowhere else the winds of possibility.”4 The very site where the image was made no longer functioned as mere background to a central subject, but also occupied as important of a role as any other element within the composition. Although this paper is centered on photography, an analysis of Joan Miró’s painting titled: “Photo: this is the color of my dreams,” dated to 1925 (figure 2) should help foreground how interlinked photography was – sometimes physically, often conceptually – with other media utilized by Surrealists. Miró’s painting, almost featureless, is composed of three elements: the word “photo” written in large letters on the upper left, a single patch of blue paint on the right, and inscribed below it the phrase: “This is the color of my dreams.” Most commentaries on the painting concentrate on the patch of blue paint. This seems to deny, however, the importance of the other, equally significant, element in the composition: the large calligraphic word Photo in the top left corner. This word informs the viewer that this is a reproduction of the color of the artist’s dreams, which is blue. One could argue that in order to establish the status of his blue as having the force of truth, Miró calls upon a central element in the power of photography: the way it records, apparently without commentary, but precisely and directly, whatever might be before the camera. According to Barbara Rose, nonetheless, this painting is a gesture of resistance to the increasingly prevalent role of photography within Dadaism and Surrealism. Miró, she argues, is exposing the imaginative limitations of photography, since dreams, like angels, cannot be 4 André Breton, The Lost Steps (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 4. 4 of 17 photographed.5 Yet this ignores the way that the transcriptive power of photography can itself seem magical, despite – indeed because of – its chemical directness. Photography’s very reliance on chemistry makes it seem alchemical.6 Miró’s evocation of photography as metaphor for an apparently contrary form of poetic creativity – a documentation that is also magic – finds echoes elsewhere in Surrealism. Most pointedly, there is the early remark by André Breton: “The invention of photography dealt a mortal death blow to old means of expression, as much in painting as in poetry, where automatic writing… is a veritable photography of thought.”7 While automatic writing is the direct, unedited, and unmediated workings of the unconscious, in a photograph, the Surrealist realism must consist of more than mere reproduction of the surface of reality. It must also try to reveal connections and meanings normally obscured or overlooked. In photography, the idiosyncrasies of la vie quotidienne can become forever frozen in time, thus creating a whole host of new possibilities and strange discoveries to both the photographer and the viewer. Arthur Rimbaud once observed: “the artist is a visionary […] his task is to render visible and legible whatever lay beneath, or beyond the visual.”8 For that reason, it is photography’s very nature, due to both its connection and disconnection with reality, as well as its mechanical and automatic qualities, that make it the perfect Surrealist tool. The Surrealist unwrapping of this social fantasy, the disturbance and dislocation of the commonplace - otherwise imperceptible in the course of everyday life - is most prominently manifested in the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Even though his work never appeared in any Surrealist publications, Cartier-Bresson made some of his best early pictures out of the space 5 Barbara Rose, Miró in America (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1982), 16. Ian Walker, City Gorged with Dreams: Surrealism and Documentary Photography in Interwar Paris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 80. 7 André Breton, The Lost Steps (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 60. 8 Arthur Rimbaud; quoted in Christian Bouqueret, Introduction to Surrealist Photography (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007), unpaginated. 6 5 of 17 between the event and its photograph, between the obvious and the elusive. This would later coin the idea of the decisive moment, which Christian Bouqueret best described as: A concept devoid of ‘magic,’ the decisive moment is an extraordinary skill at extrapolating signs, the visible marks of that which lies behind things, and at perceiving the dislocations and surreptitious anomalies that can dramatically transform an ordinary or even picturesque scene into something strange and deeply disturbing.9 In 1976, Cartier-Bresson, then at the height of his reputation as one of the most important and influential of documentary photographers, decided to use a quotation from André Breton as the epigram for an anthology of his pictures: “Actually it’s quite true that he’s not waiting for anyone since he’s not made an appointment, but the very fact he’s adopting this ultra-receptive posture means that by this he wants to help chance along, how should I say, to put himself in a state of grace with chance, so that something might happen, so that someone might drop in.”10 Not only did Cartier-Bresson, through this quotation, emphasized the vital role that Surrealist notions of chance had in the formation of his work method in the early 1930s, but he also implied that this influence had underpinned his work ever since. This influence is apparent in Cartier-Bresson’s La Place de l‘Europe from 1932 (figure 3). In this photograph, Cartier-Bresson captured a man frozen in mid-air as he jumps over a puddle. The photograph depicts the exact moment in which the subject had his legs extended as he leaps over the flooded terrain. His image is reflected on the water below. In the top left corner of the picture, juxtaposed to the figure of the man jumping, a poster of a dancer almost precisely mimics the man’s action. Similarly, the reflection of the poster appears mirrored on the water below. The figures are silhouetted against a deserted landscape next to a railroad. The 9 Bouqueret, Surrealist Photography, unpaginated. Henri Cartier-Bresson, Henri Cartier-Bresson (New York: Aperture, 1976), unpaginated. 10 6 of 17 photograph is unusually dark for Cartier-Bresson, capturing the gloom of a northern city in the winter. The rhythm between the workman and dancer has a nagging pointlessness, which Breton found so haunting in the chance juxtapositions of street posters and reality.11 There is an unsettling quality to this image. The disquieting nature of the photograph lies in its setting, a sort of wasteland of indecisiveness, a terrain vague. The site itself, behind the railway station, is a site of passage and flux, a place that is also a “non-place.” The photograph serves no apparent social purpose. Rather, it records a sliver of time and space. It memorializes and creates an image that can only exist as a photograph, for its surreality rests in the welding together of the real and the constructed. That man was once there, but now he is a flat silhouette, dynamic yet forever frozen. His suspension in mid-air is just a function of the camera’s ability to stop motion. But this does not explain the picture. Indeed, like many of Cartier-Bresson’s early pictures, its power lies precisely in its refusal of explanation. On other occasions, this refusal seemed even more deliberate. In Valencia in 1933, Cartier-Bresson photographed a small boy against a gouged and battered wall (figure 4). The boy looks up as if in an expression of happiness. One might take it, however, as a representation of disorientation, or even of mental disturbance. Ben Maddow reported that the boy had thrown a ball into the air and was waiting for it to come down.12 That, in fact, may have been the original event, but one which has long since been gone. The ball is a red herring. It is eliminated from the frame at the crucial instant the image was made. It no longer exists, just as the man jumping the water will never land. The photographer is not interested in reproduction, but rather in exploring the ontological gaps in photography, the world that lays out of the shot, with the suggestion that reality has been interrupted in such a manner that the viewer is 11 12 André Breton, Nadja (New York: Grove Press, 1960), 129. Ben Maddow, Faces (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1977), 494. 7 of 17 challenged to ponder about what actually happened and what appears to have happened. Photographically, this may be a decisive moment, but it is hardly one that draws together the elements of the scene in order to explicate them. In narrative terms, the photograph is rather inconclusive. Ultimately, the viewer is confronted with an unresolved ambiguity that is Surrealist to the core. A comparison between the work of Cartier-Bresson and other photographers working in Paris around the same timeframe can also help illustrate the idea of Surrealist documentary photography. One of André Kertész’s earliest 35mm pictures was taken in 1928 in the Paris suburb of Meudon (figure 5). This photograph has become one of the key images in a Surrealist reading of his photography.13 Kertész’s image has some features in common with the previously seen La Place de l‘Europe by Cartier-Bresson (figure 3). The setting is also some sort of vague terrain through which a railway line passes. Both photographs captured a fleeting moment when relationships are formed by the camera that a split second later will have gone. But beyond that, the pictures are quite different. Rather than the single event on which Cartier-Bresson’s photograph is centered, the effect of Kertész’s image relies on the relationships between the man and the train, the man and his package, and the man and the photographer. Caught in mid-stride, the man heads toward the camera and, by seemingly staring at the photographer, invites the viewer into the scene. The power of this photograph rests in the harvesting of time and motion that even though suspended is also fleeting; the train will continue to its destination, and the man will complete his errand. Whereas Cartier-Bresson’s vision is fragmented and dissociative, Kertész’s photograph appears more complete. In either case, however, the cityscape and life permeate the imagination of both photographers. 13 Nancy Hall-Duncan, Photographic Surrealism (Cleveland: New Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1979), 21. 8 of 17 To see works that foreshadow the Surrealist fascination with the urban environment, nonetheless, one must refer back to paintings made by Giorgio de Chirico before the First World War. Albeit much of de Chirico’s work was rooted on a longing for the classical past - which opposed the modernist inclinations of Surrealists - it was often also possible to transpose his urban landscapes into modern Paris. In fact, de Chirico himself did so when he named one of his paintings Gare Montparnasse, The Melancholy of Departure (figure 6). Far in the distance, beyond the hard-lined, solid-colored grandiose of the abstracted façade, a small black train is belching out smoke as it enters the station. Only two small figures, their shadows cast on the ground, seem to inhabit an otherwise desolate landscape. They head toward the station, where the train is soon to arrive. Similar to Kertész’s Meudon (figure 5), de Chirico stops motion and time and thus presents the viewer with an instant that would otherwise be forever gone. Again, it is what lies outside the composition, in the subconscious, that makes the image. The once deserted landscape is about to become populated by those who arrive; the figures in the distance will soon catch the train, which will invariably continue to its final destination. De Chirico transcends the banality of urban landscapes and creates, in turn, a world that could be real, but for its polysemy, remains enigmatic; therein lays its surreality. In Le Surréalisme et la peinture, Breton recognizes in de Chirico’s paintings an effective cityscape of the imagination, a concept which is inherently Surrealist.14 “De Chirico’s city was not only a space to put next to the actual city, but also one to place – palimpsest like – over it, so that the actual city and the imagined city were fused. Reality was infiltrated by the dream, the present infiltrated by the past,”15 explained Ian Walker. For Breton, de Chirico represented the 14 15 André Breton, Surrealism and Painting (New York: Icon, 1972), 13. Walker, Interwar Paris, 37. 9 of 17 force majeure in the creation of a truly modern mythology, one upon which the perception of time and space needed to be revisited. The dual image of the street as a site of mystery and pleasure, threat and invitation, also found expression in Brassai’s work. Unlike Cartier-Bresson, but similar to many Surrealists, Brassai was a nightwalker that meandered about the streets of Paris photographing the city with its characters at night. His photographs often recorded the darker and more obscure corners of the city. In one of Brassai’s photographs entitled Brothel dated to 1933 (figure 7), a mirror is placed in the corner of a space - in this case the room of a brothel – showing the occupants of that room. The mirrors are framed by the rectilinear shape of the armoire, which is outlined by the geometric patterns of the wallpaper. In front of it, a man, dressing, stands looking into the mirror on one of its doors, while his partner’s naked body is captured in a virtual image that is framed by the mirror on the other door. Present only in reflection, the woman is displaced from her position in real space and transported to a relation of direct spatial contiguity with her client. In the meeting that is enacted on the picture plane alone, the couple produces a transient, fleeting sign of the meaning of their encounter, its anonymous sex represented by their faceless juxtaposition in the mirrors, by the closure of two bodies back to back in real space. Rosalind Krauss in her article Nightwalkers explained that Brassai often used the technique of mise en abyme, the placement within one representation of another representation that reduplicates the first.16 The corner of the room fills the entire frame of the photograph; the frame of the armoire contains the image of the couple; the mirror on the left side contains the image of the woman. But one can also read it from inside out, so that the obvious virtuality of what is present only in the mirrored space spreads outward to include and encompass the imaged world on the other side 16 Rosalind Krauss, “Nightwalkers,” Art Bulletin 41, no. 1 (Spring, 1981): 37. 10 of 17 of the mirror and finally the photograph as a whole. The viewer is forced to acknowledge that the virtuality of the figures seen in reflection is no greater, or less, than the virtuality of the real figures seen in the direct representational field of the photograph. According to Christian Bouqueret: “Brassai exposes the reality that has been stripped of its familiar masks, and allows us a glimpse of connections, gaps, faults – a great network which is normally unseen and which constitutes precisely what Breton had despairingly hoped for in the photographs that illustrated his novel Nadja.”17 It is because of this process of transformation of the real into a field of representations that one might come to read the very bodies of these actors as symbols, as a surreal depiction of a suspended reality. Furthermore, eroticism is also undoubtedly a mechanism through which Surrealism is often manifested. Whereas Brassai and Kertész came into contact with Surrealism when they were already well established, Cartier-Bresson discovered it before he began to make photographs and, therefore, the influence was much deeper. Unlike Brassai and Kertész, Cartier-Bresson was happy to acknowledge the importance of that influence. Indeed, his adherence to the fundamental principles of Surrealism were such that “there is justification for the opinion that in the early 1930s Cartier-Bresson was the best and most mature of the Surrealist photographers, although his work does not appear in any of the Surrealist periodicals.”18 Paradoxically, understanding Cartier-Bresson’s early works becomes crucial to fully comprehending the concept of Surrealist documentary photography, even as it was peripheral to the Surrealist movement itself. There are enough internal clues to suggest that even though the questions raised here were not consciously theorized by the Surrealists at the time, they were intuitively embedded in 17 Bouqueret, Surrealist Photography, unpaginated. Van Deren Coke and Diana C. Dupont, Photography: A Facet of Modernism (San Francisco: Museum of Art, 1986), 76. 18 11 of 17 the ways that pictures were made and the ways they were used. If there is a common denominator to these photographs, then it is that they betray willingness on the part of the photographer to record the visible, rather than a desire to modify or subvert it. Insistence on dreaming was never meant to separate the surreal from the real, to relegate the former to a zone where imaginative activity might be kept safely remote from the world of observed reality. “What is admirable about the fantastic is that there is no longer anything fantastic: there is only real,” 19 Breton once observed. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the Surrealists favored photography as the medium for its experiments. After all, Breton wanted a tale that would be more realistic than a novel. There are also many lessons here for the photographic contemporary practice: lessons about how the documentary genre can incorporate subjectivity, ambiguity and reflexivity; and about how images can be made which acknowledge both their constructed and indexical qualities – images that can be expressions of both desire and fragments from the real world. 19 André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), 4. 12 of 17 Figure 1. Man Ray, American (1890-1976). Marquise Casati. 1922, silver gelatin print. Figure 2. Joan Miró, Spanish (1893-1983). Photo: this is the color of my dreams. 1925. Figure 3. Henri Cartier-Bresson, French (1908-2004). La Place de l’Europe, Paris 1932, Silver gelatin print. 13 of 17 Figure 4. Henri Cartier-Bresson, French (1908-2004). Valencia, 1933, Silver gelatin print. Figure 5. André Kertész, Hungarian (1894-1985). Meudon, 1928, Silver gelatin print. 14 of 17 Figure 6. Giorgio de Chirico, Italian (1888-1978). Gare Monteparnasse (The Melancholy of Departure), 1914. Oil on canvas, 55.1 x 112 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Figure 7. Brassai, Hungarian (1899-1984). Brothel, 1933, Silver gelatin print. 15 of 17 Abridged Bibliography Aragon, Louis. Paris Peasant. Trans. Simon Watson Taylor. Boston: Exact Change, 1994. Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1980. Bazin, André , and Hugh Gray. “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” Film Quarterly, Vol. 13, no. 4 (Summer, 1960): 4-9. Bouqueret, Christian. Introduction to Surrealist Photography. London: Thames & Hudson, 2007. Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Trans. Richard and Hellen R. Lane. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969. Breton, André. Nadja. New York: Grove Press, 1960. Breton, André. Surrealism and Painting. New York: Icon, 1972. Breton, André. The Lost Steps. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996. Breton, André. What is Surrealism? Selected Writings. Ed. Franklin Rosemont. New York: Pathfinder, 1978. Buckland, Gail. Reality Recorded: Early Documentary Photography. Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1974. Cartier-Bresson, Henri. Henri Cartier-Bresson. New York: Aperture, 1976. Deren C., Van, and Diana C. Dupont. Photography: A Facet of Modernism. San Francisco: Museum of Art, 1986. De Sanna, Jole. “Giorgio de Chirico – André Breton: Duel à mort.” Metafisica, no. 1-2 (2002): 62-87. Guerrisi, M. La nueva pittura: Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, Derain, De Chirico, Modigliani. Torino: DellErma, 1932. Grindon, Gavin. “Surrealism, Dada, and the Refusal of Work: Autonomy, Activism, and Social Participation in the Radical Avant-Garde.” Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 34, no. 1 (2011): 79-96. Hall-Duncan, Nancy. Photographic Surrealism. Cleveland: New Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1979. Hammond, Paul. The Shadow and its Shadow. London: British Film Institute, 1978. Hollier, Denis, and Rosalind Krauss. “Surrealist Precipitates: Shadows Don’t Cast Shadows.” October, Vol. 69 (Summer, 1994): 110-132. Hubert R., Renée. “The Fabulous Fiction of Two Surrealist Artists: Giorgio de Chirico and Max Ernst.” New Literary History, Vol. 4, no. 1 (Autumn, 1972): 151-166. 16 of 17 Hugnet, Georges, and Margaret Scolari. “In The Light of Surrealism.” The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, Vol. 4, no. 2/3 (1936): 19-32. Krauss, Rosalind. “Night Walkers.” Art Bulletin, Vol. 41, no. 1 (Spring, 1981): 33-38. Krauss, Rosalind. “The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism.” October, Vol. 19 (2005): 3-34. Krauss, Rosalind. Under Blue Cup. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2011. Maddow, Ben. Faces. Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1977. Nadeau, Maurice. The History of Surrealism. Trans. Richard Howard. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. Olin, Margaret. “Roland Barthes’s ‘Mistaken’ Identification.” Representations, vol. 80, no. 1 (Fall 2002): 99-118. Rose, Barbara. Miró in America. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1982. Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Picador, 1977. Walker, Ian. City Gorged with Dreams: Surrealism and Documentary Photography in Interwar Paris. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002. Walker, Ian. So exotic, So Homemade: Surrealism, Englishness and Documentary Photography. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007. 17 of 17