The Common

Core Made Easy

A Collection of

Tips, Resources,

and Ideas

Part

One

by Lauren Davis

Eye On Education

6 Depot Way West

Larchmont, NY 10538

www.eyeoneducation.com

(888) 299-5350 phone

(914) 833-0761 fax

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips,

Resources, and Ideas

By Lauren Davis

This eBook is adapted from Lauren Davis’ online blog series Comments

on the Common Core. In this bi-monthly series, Lauren shares her insights

and opinions on the Common Core State Standards and keeps readers

apprised of new developments. Readers are invited to provide their own

opinions and comments in the comments section of each blog post, which

goes live two Wednesdays a month.

Table of Contents

Why Computer-Based Scoring for the Common Core Makes Me Uneasy .............................................. 2

How to Shift From Teaching Persuasion to Teaching Argument ................................................................ 4

How to Design Text-Based Questions (and Teach Students to Answer Them!) ..................................... 6

Resources for Finding Informational and Nonfiction Texts .......................................................................... 7

Helping Students Navigate Informational Texts ............................................................................................... 9

How to Design Open-Ended Assignments to Meet the Common Core ................................................ 10

Teaching Opinion Writing in the Elementary Grades ................................................................................... 13

Assessing the PARCC Assessments ...................................................................................................................... 15

Moving Students Beyond Index Card Presentations .................................................................................... 17

10 Tips for Teaching Grammar According to the Common Core .............................................................. 19

10 Tips for Teaching Grammar According to the Common Core (Infographic) ................................... 21

1

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

Why Computer-Based

Scoring for the Common Core

Makes Me Uneasy

W

hen I was in high school, I was selected, along with two other students, to participate in a timed

writing contest for an organization whose name I can’t recall. On the day of the competition, my two

challengers (extremely intelligent and hard-working students) walked into the room each carrying a

thesaurus. During the contest, they furiously searched for

fancy and intelligent words to pepper into their writing.

I was totally intimidated. It hadn’t dawned on me to

bring a thesaurus, and it was too late for me to get one.

I figured that I was out of the running and that my essay

would sound dumb compared to theirs.

I was wrong—I actually won. The committee members

told me that I was selected in part because of my clear,

accessible language. They emphasized that the purpose

of writing is to communicate, not to try and sound smart.

It didn’t matter how fancy my competitors were with

their language if they weren’t getting their ideas across.

That was an important lesson for me, and I kept it in mind when I became a teacher. I made sure to show

students how to really use and understand new words, not just pluck them out of a thesaurus or dictionary,

memorize them, and throw them into a sentence. I also spent time on word choice. Sometimes you do need that

bigger word for conciseness and accuracy, but sometimes a few smaller words are better. Sometimes you need

to define terms for your reader, and sometimes you don’t. We must teach students to make conscious language

decisions based on audience and purpose.

But now I’m worried. Will these principles of effective communication get tossed out the window when the

Common Core assessments are released?

The Common Core State Standards do emphasize audience and word choice, but the new automated essay

scorers, which might be used for the CCSS assessments, seem to value long words—even if meaningless and

used incorrectly!—over shorter words.

2

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

For example, let’s look at the e-Rater, the new automated

scorer from Educational Testing Services (http://nyti.ms/

Jp2XmW). According to The New York Times, research from

MIT shows that the e-Rater prefers length over quality. “A

716-word essay… that was padded with more than a dozen

nonsensical sentences received a top score of 6; a wellargued, well-written essay of 567 words was scored a 5.” The

e-Rater also doesn’t like short sentences and sentences that

start with and or or. And the e-Rater doesn’t care about the

quality of evidence in your argument (all the facts could be

wrong) as long as you have evidence. (Did I lose points for

that sentence?) Students can make stuff up. Is that what we

want to teach them about good writing?

That being said, the two consortia working on Common

Core assessments (PARCC and SMARTER Balanced) are still

designing their systems, so it’s too soon to confirm whether

they’ll definitely use automated scorers, and if so, which kind

they’ll use. I’m just panicking because I don’t like the early

rumors! I will continue to follow the developments and keep

you posted as best I can.

The Common Core

State Standards do

emphasize audience

and word choice, but

the new automated

essay scorers, which

might be used for the

CCSS assessments,

seem to value long

words—even if

meaningless and used

incorrectly!—over

shorter words.

This post was originally published on August 15, 2012.

3

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

How to Shift From

Teaching Persuasion

to Teaching Argument

P

ersuasive writing has been very popular in ELA classrooms in recent years. During a persuasive writing unit,

students are typically asked to write a letter or essay convincing someone to do or believe something.

Students are taught persuasive techniques such as bandwagon, glittering generalities, and snob appeal.

Now the Common Core is moving teachers from persuasion to argument. This shift might be confusing to

people who see “persuasion” and “argument” as the same thing. However, the Common Core’s authors draw a

distinction between the terms.

When writing to persuade,… [one] common

strategy is an appeal to the credibility,

character, or authority of the writer… Another

is an appeal to the audience’s self-interest,

sense of identity, or emotions… A logical

argument, on the other hand, convinces the

audience because of the perceived merit

and reasonableness of the claims and proofs

offered rather than either the emotions the

writing evokes in the audience or the character

or credentials of the writer. (The Common Core

State Standards, p. 24)

Now, the Common

Core is emphasizing

the importance of

focused, text-based

questions over

personal opinionbased ones.

In other words, argument is about logic, not emotion. The Common Core authors also say that argument has a

“special place” in the standards, since it is a crucial genre for college and careers.

So how do teachers adjust their lessons to fit the new requirements? Here are some strategies for teaching

argument:

• Teach concession-refutation. Students should be aware of and address the other side of an issue, not

just their own side. You may need to give students sentence frames. You can find some on the website

of Eye On Education’s author Amy Benjamin. Go to http://www.amybenjamin.com and click on

4

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

•

•

•

•

“Writing” under Common Core—the sentence frames are part of that PowerPoint.

Show students how to avoid common logical errors. A list of common logical fallacies (with examples)

can be found at Purdue OWL (http://bit.ly/ZFrKLI). The site www.fallacyfiles.org contains additional

examples of logical fallacies in the world. Students can even contribute to the site.

Analyze mentor texts with students. For example,

students can look for examples of concessionrefutation in newspaper articles, and they can see

how an author supports his/her claims with logical

and clear evidence.

Teach students how to marshal facts. Effective

argumentation requires strong evidence. Students

need to learn how to gather that evidence and how

to incorporate it into their writing. Don’t just let

students go to Google and pick the first thing they

see. Teach students how to create focused search

terms; how to narrow their search results; how to

evaluate a website for reliability accuracy, currency,

and bias; how to incorporate information into their

essays (when to quote and when to paraphrase, and what constitutes a real paraphrase vs. plagiarism);

and how to cite sources.

Teach students some academic vocabulary involving argument writing—claim, evidence, marshal,

concession, refutation, etc.

And even though argumentation should be your main focus based on the Common Core’s requirements, I’m all

for throwing in some persuasive lessons if time permits. Teaching students to understand emotional appeals will

help them become more media literate and savvy about propaganda in the world around them. I’d hate to see

that left out completely. You could also do argument writing that includes elements of persuasion, since a lot of

authors combine facts and emotion.

This post was originally published on August 29, 2012.

5

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

How to Design Text-Based

Questions (and Teach Students

to Answer Them!)

W

hen I was a teacher, it was common practice to ask students for their personal responses to literature. I

did that a lot in my classroom as a way to engage reluctant readers in a story. Now, the Common Core is

emphasizing the importance of focused, text-based questions over personal opinion-based ones.

This shift is making some teachers uneasy. They’re wondering if they have to toss their provocative personalresponse questions out the window. My answer is no, they don’t. The CCSS aren’t outlawing such questions. But

they are saying that such questions should come later, once it’s clear that students understand the language of

the text. According to Common Core authors David Coleman and Susan Pimentel:

An effective set of discussion questions might begin with relatively simple questions requiring

attention to specific words, details, and arguments and then move on to explore the impact

of those specifics on the text as a whole. Good questions will often linger over specific

phrases and sentences to ensure careful comprehension… Often, curricula surrounding

texts leap too quickly into broad and wide-open questions of interpretation before

cultivating command of the details and specific ideas in the text. (Coleman and Pimentel, p. 7)

In other words, don’t ask broad or opinion-based questions until it’s clear students understand the work itself—

otherwise students will be able to answer from their own experiences and won’t be learning critical reading skills.

Begin by having students grapple with a text’s words, sentences, and paragraphs so they can create meaning

from the words on the page and not just from their own minds. For example, if you’re teaching Macbeth’s

soliloquy “Tomorrow, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow,” don’t start with general questions about the futility of life. First,

be sure that students understand the language of the soliloquy. Ask questions like, “How does the repetition of

‘tomorrow’ affect the tone?”

Make sure your questions require students to go back to the text and reread a word or passage in order to gather

evidence or construct a response. Spend time teaching students how to go back to the text. That skill might not

come easily to them. (Students like to be “quick”—they are often tempted to say the first thing that comes to

their minds and will forget to go back and gather evidence.)

• For a helpful lesson on teaching students to answer a text-based question step-by-step, check out

Common Core Literacy Lesson Plans: Ready-to-Use Resources, 6-8 (http://bit.ly/W2Uvzz).

This post was originally published on September 12, 2012.

6

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

Resources for Finding

Informational and

Nonfiction Texts

I

’ve heard some teachers say that it’s difficult and time-consuming to find

appropriate nonfiction and informational texts to meet the Common Core.

I’ve put together some resources below. I hope these are helpful:

1. News magazines for kids

• Check out Scholastic’s news magazines, including Scholastic News,

Storyworks, and Superscience— http://bit.ly/lOqVpD. (You can

subscribe to the print editions, and some articles are free online.)

Consider doing lessons that tie current events to past events in

history. English and social studies teachers can collaborate on

this. Note that many of Scholastic’s articles list the Lexile levels

and are correlated to the Common Core. Many of the articles are

informational and include charts, graphs, maps, and links to online

videos. Action magazine even has differentiated articles—one

article written at three different levels.

• Time For Kids (http://bit.ly/cLlFU) provides a variety of engaging

health, sports, science, news, and entertainment articles. Teacher’s

guides and worksheets are available.

2. Text sets

• The Reading and Writing Project has put together some lists

of text sets on science and history topics—http://bit.ly/LvecXJ.

The list includes links to the actual articles, not just bibliographic

information. You won’t have to spend time hunting down the

recommendations.

7

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

3. Opinion pieces

• I’m a big fan of The New York Times’ Room for Debate blog (http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate).

It is especially helpful with teaching argument writing. Yes, sometimes the articles are too difficult for

kids, but usually they are pretty short and accessible. You can often find two or more articles on the pro

side and two or more articles on the con side. I also love The New York Times’ The Learning Network

(http://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/). The lesson plans often link to the newspaper’s more accessible

(but still complex and challenging) articles.

4. Newspaper and magazine articles

• Check to see if your school or public library subscribes to the searchable database EBSCO (http://www.

ebsco.com/). It includes articles from magazines and newspapers written at different reading levels, as

well as e-books and audio books.

5. Notable nonfiction books

• Go to the American Library Association’s website and look at the different book lists under Book, Print,

and Media Awards— http://bit.ly/WjXsgO.

Additional Tips

• Don’t forget to collaborate with teachers across the curriculum. An English teacher might want to use

something from the students’ social studies textbook and tie that to a novel students are reading in

class.

• The Common Core’s Appendix B includes a variety of exemplary texts. Some people have been

complaining that these recommendations are out of date, but remember that they’re just exemplars

to give you a sense of text complexity. You’re not required to teach those exact ones, though you may

want to teach some of them if they appeal to you.

• Don’t forget to include a wide variety of informational topics—not just the obvious ones like animals

and the weather. For examples, students might be interested in reading Chew On This about the fastfood industry, and older students might be interested in reading Outliers, about how people become

successful. In the elementary grades, the standards ask that students read informational texts to build

content knowledge, not just to gain reading skills, so think in terms of variety.

• If you’re not sure of a nonfiction book’s reading level, check out Lexile’s Find a Book Site (http://www.

lexile.com/fab/). Don’t forget that you shouldn’t rely on Lexiles alone. Use your own judgment and

consider the interest level, background knowledge required, etc.

This post was originally published on September 26, 2012.

8

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

Helping Students Navigate

Informational Texts

T

he Common Core State Standards call for big increase in the amount of time spent on informational texts.

This is a huge shift for teachers who are used to focusing on fiction. Here are some strategies for helping

students navigate those texts:

• Teach students to discover and understand a text’s structures and features. Ask students why an author

would use a certain element or visual. It’s not enough for students to understand the information

in a graph (e.g., the graph shows that 75% of students like chocolate ice cream). They should try to

determine why the graph is included in

the first place and how it helps support the

information in the text.

• When possible, incorporate academic

vocabulary into your lessons (along with

the content-area vocabulary). For example,

depending on the text and your students’

level, you might be able to introduce

academic terms such as bar graph, icons,

glossary, index, and subheading. Doing so will

teach students the material and also teach

them how to talk about the material in the

future.

• As you do with literary texts, teach students to do close readings, and show them that it’s okay to have

to reread something if they don’t understand it at first. Use think alouds to show how you question a

difficult text as you read.

• Teach students how to figure out the meanings of unknown words. Teach context clues, and help

students understand when they can and can’t use them. Sometimes, an author doesn’t provide

enough clues, and readers need to check word meanings in a dictionary. Sometimes the authors of

informational texts define words in a glossary.

• Use visuals. Graphic organizers such as Venn diagrams, cause-effect flow charts, and timelines will help

students analyze the information in a text and compare two texts.

• Teach the different organizational methods an author might use (cause-effect, problem-solution, etc.)

as well as the key words that help readers determine structure. For example, a time-order essay might

include sequencing words such as first, next, etc.

9

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

• Include prereading and scaffolding activities that help students with “words and concepts that are

essential to a basic understanding and that students are not likely to know or be able to determine

from context” (Coleman and Pimentel, Revised Publishers’ Criteria for the Common Core State

Standards in English Language Arts in Literacy, K–2, p. 8). However, be careful of prereading activities

that summarize the text or reveal the major ideas of the text. Such activities may make it harder for

students to discover ideas on their own.

• Have students discuss the text and write about it. Writing helps students work independently through

their thinking about a text (Coleman and Pimentel, p. 9).

• Ask text-based questions, and show students how to go back to the text for answers. When students

respond to a question, make sure they say how they got their answers. With elementary students, you

can ask, “How did you know that?” With older students, you can expect them to cite specific words

from the text to support their ideas.

This post was originally published on October 10, 2012.

10

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

How to Design Open-Ended

Assignments to Meet

the Common Core

T

he Common Core State Standards aim to help students become independent learners and thinkers.

Students should “become self-directed learners, effectively seeking out and using resources to assist them,

including teachers, peers, and print and digital reference materials” (The Common Core State Standards,

p. 7). Giving students questions with predetermined answers will not accomplish that goal. Instead, try to make

your writing and research assignments more authentic and open-ended, so students can discover information

on their own.

But what exactly is an open-ended assignment? It doesn’t mean

asking students a subjective question and accepting all of their

random opinions. In Students Taking Charge: Inside the LearnerActive, Technology-Infused Classroom (http://bit.ly/XLybda), Nancy

Sulla gives a great example of what an open-ended assignment

does and does not look like. First, she explains what an open-ended

assignment is not.

A typical assignment found in elementary classrooms

today is to write a report on dinosaurs. This simply

requires students to locate and report back information

with no open-ended aspect related to the content, and

very little to the product. (Sulla, p. 25)

Asking students to find and report back information might be useful

in some circumstances but will not promote students’ independent

thinking skills.

Open-ended

assignments are

trickier to create,

but they will lead

to higher levels of

learning, and they

will also increase

engagement since

students will feel

responsible for their

own learning.

Sulla then provides an example of a slightly better assignment that’s still not fully open-ended.

A teacher might assign a project in which students will create a dinosaur exhibit for a

local museum with information on the various dinosaurs that once walked the earth.

While this may sound like an engaging project, it is only slightly more open-ended than

the first, with the open-endedness related more to the product than the content. (Sulla,

11

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

p. 25)

In other words, that kind of project might seem fun for students because it involves art, but it’s not having them

discover and learn content on their own.

Finally, Sulla gives an example of a real open-ended assignment.

A more open-ended problem would be to ask students

to consider that scientists may be able to clone a

dinosaur from DNA and wish to create a habitat in

which it can live. The students would have to learn

about the dinosaur and make plans to accommodate

its needs, this providing a more open-ended challenge

than the other two. (Sulla, p. 25)

The cloning assignment challenges students to think about content

in different ways and apply knowledge, not just regurgitate it.

Open-ended assignments are trickier to create, but they will lead to

higher levels of learning, and they will also increase engagement

since students will feel responsible for their own learning.

This post was originally published on October 24, 2012.

12

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

Teaching Opinion Writing in

the Elementary Grades

E

veryone’s been buzzing about the Common Core’s emphasis on argument writing (called opinion writing

in the elementary grades). The standards are very specific about what aspects of this genre to teach at each

grade level, K–12. In the elementary grades, students have to learn the basics about facts and opinions.

This sets the foundation for the more sophisticated writing they’ll be required to do later. But how do we teach

students those basics? Here are some ideas, broken down by grade-level requirements. (Note that I’m focusing

on teaching opinions and evidence, but you’ll also need to teach paragraph format and organization.)

• Kindergarten: Students need to form an opinion.

Help students discover what an opinion is and how it differs from a fact. For example, ask students

to share their favorite color or what they think is the best flavor of ice cream. Write some of their

statements on the board. Show that favorite and best are opinion words. Emphasize that people in the

class have different opinions; there are no right or wrong answers. Then show how a fact is different.

For example, “I love chocolate ice cream” is a fact, not an opinion. Have students practice forming and

stating an opinion by writing a sentence and/or drawing a picture that represents their opinion. If you

want to use a text for this lesson, you can ask students which character is their favorite or what they

found most interesting about the text.

• Grade 1: Students need to include a reason for their opinion.

Ask students why they prefer a certain thing. You can provide students with sentence frames, such as,

“My favorite ______ is ______ because…” Emphasize that because is the connecting word that gives

their reason. Have students share their sentences orally and write them down. You can use mentor

texts for this lesson. For example, if a character puts on a red sweater because red is her favorite color,

remind students that it’s a fact that she put on the sweater, but it’s her opinion that red is the best

color.

• Grade 2: Students need to provide linking words to connect their opinion and reasons.

Teach students basic linking words such as and, also, and because. Help students discover what those

words mean by putting them in sentences and asking their purpose. Then have students use those

words in their own sentences. Note that at this grade level and beyond, students should provide more

than one reason for an opinion.

• Grade 3: Students need to use linking phrases, not just linking words.

Focus on more sophisticated linking words and also phrases. Teach terms such as because, therefore,

since, and for example.

13

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

• Grade 4: Students need to use reasons, information, and facts to support their opinion.

The previous grade-level standards require students to provide reasons. Once you get to grade 4, the

standards require reasons, information, and facts. Teach students how to understand and use these

different kinds of evidence. Show students basic ways to gather information and facts. Students can

pull information from an article you provide or conduct basic Internet research. At this grade, you

should also teach more sophisticated linking terms, such as for instance, in order to, and in addition.

• Grade 5: Students need to group their reasons in a logical way.

They need to use linking words, phrases, and clauses to tie their opinions to their reasons. Provide

graphic organizers to help students group their reasons. Teach more sophisticated linking terms, such

as consequently and specifically.

This post was originally published on November 7, 2012.

14

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

Assessing the PARCC

Assessments

D

uring the past two years, educators have been transitioning to the Common Core with a big question

looming over their heads: What will the assessments look like?

We’re finally starting to get at least a partial answer to that question. PARCC (Partnership for Assessment of

Readiness for College and Careers— http://www.parcconline.

org/), one of the two consortia working on the assessments, has

released some item and task prototypes to give us a sneak peek

The Common Core is

at what they are planning (http://bit.ly/TQ6NZ9).

Although the prototypes are in draft form (the assessments

won’t be finalized and administered until 2014–15), it’s still

helpful to study them to see where things are headed. I recently

spent some time examining them myself, and I recommend

that all educators do the same. Here’s a rundown of some of the

things I like and don’t like so far.

all about high-quality,

complext texts, and...

PARCC wants to stay

true to that on their

assessments.

Some of the things I find appealing

• The use of authentic texts. PARCC is using authentic texts, not “fake” texts that are commissioned solely

for the test. I’m glad to hear that. I spent some time as an editor of test-prep books, and I have read

plenty of dreadful, commissioned passages. The Common Core is all about high-quality, complex texts,

and I’m glad PARCC wants to stay true to that on their assessments.

• The new technology-based question format. PARCC has developed a few innovative item types. I

particularly like the item called Technology-Enhanced Constructed Response (TECR). This format allows

students to prove their comprehension and cite textual evidence by dragging and dropping, cutting

and pasting, shading text, etc. rather than having to choose one of four multiple-choice options.

For example, there might be a question asking students what word best describes a character’s

relationship with another character. Then, in a follow-up question, students drag and drop a sentence

from the text that supports their answer (http://bit.ly/WiDgG9). I love this format because it gives

students the ability to think on their own; they won’t be fooled by “distracters” and bad multiple-choice

writing. I was never great at taking multiple-choice tests because I second-guessed myself. I’d think, I

know C is right, but what if A is right, too, and I just don’t realize it? The new format allows students to

demonstrate their actual comprehension and not just their ability to answer multiple-choice questions.

15

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

• The added supports for students with special needs. PARCC promises to include different computer

supports to help students with disabilities during the assessment. I’m not sure what the supports will

look like, but this sounds promising.

What concerns me

• Students’ writing will be scored by people but also by computer, and I am very skeptical of computerbased scoring (see p. 2).

• I don’t know how some districts are going to be able to handle the technology requirements for these

tests. I know this is a huge issue right now.

This post was originally published on November 21, 2012.

16

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

Moving Students Beyond

Index Card Presentations

W

hen I was in middle school, I had to prepare an oral presentation on a famous woman in American

history. I remember sitting on my bedroom floor, surrounded by index cards. On each card, I wrote a

few sentences about the person’s life. A few days later, I read my index cards to the class. That was it—

that was my oral presentation. I don’t think I got much out of that assignment. I guess I learned details about a

famous person’s life (info I have since forgotten… I don’t even remember the person I did!), but I certainly didn’t

learn how to deliver an effective presentation and engage an audience. I didn’t learn those skills until much later,

when I started working in teaching and publishing.

I’m glad those kinds of “flat” index card presentations

are becoming a thing of the past. The Common

Core now requires that we teach students to

deliver much more engaging, effective, real-world

presentations using technology. According to the

standards, students in grades 6–12 must be able

to “make strategic use of digital media and visual

displays of data to express information and enhance

understanding of presentations” (CCSS Speaking and

Listening Anchor Standard 5). I like this requirement

because I think presenting information effectively is

something you should know for almost any career. So

how do teachers meet this requirement and equip

students with presentation skills? Here are some ideas:

• Before designing your lesson, consider why you want to have students use multimedia. Is it to clarify

something for an audience, or to highlight an important detail? Note that the standard changes

slightly for each grade level, 6–12. In grade 6, the standard says that students should use multimedia

components to “clarify information”; in grade 7, they should use multimedia components to “clarify

claims and findings and emphasize salient points”; in grade 8, they should use multimedia components

to “clarify information, strengthen claims and evidence, and add interest”; and in grades 9–12, they

should use multimedia components to “enhance understanding of findings, reasoning, and evidence

and to add interest.”

• Don’t just make students use digital media; teach them why it matters. Ask students how different

forms of media and visual displays can help an audience to remember information. Have students

17

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

•

•

•

•

compare and contrast the benefits and drawbacks of different forms. Have students analyze model

presentations and decide which are effective and which aren’t, and why.

Don’t forget the importance of authenticity. Give students a real-world research question or topic on

which to present.

Involve students in the assessments. After analyzing sample presentations with students, ask them to

come up with their own rubrics for evaluating an effective presentation.

Allow time for peer review. Give students class time to workshop their slides or other presentation

components with partners.

Model speaking skills and let students practice those skills. Show students how to make eye contact,

adjust their stance and volume, etc. Then give them time to practice.

For more on teaching students to deliver effective presentations, check out these resources:

• Mike Splane, a professor at San José State University, offers this helpful page of presentation tips—

http://bit.ly/bqONoy.

• Ohio Wesleyan University’s Libraries & Research Center provides these presentation guidelines—

http://bit.ly/SzT5ZW.

• Each book in the Common Core Literacy Lesson Plans series (http://bit.ly/Zm8IGH) provides gradeappropriate lesson plans for teaching students to deliver authentic, oral presentations that use

multimedia.

This post was originally published on December 5, 2012.

18

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

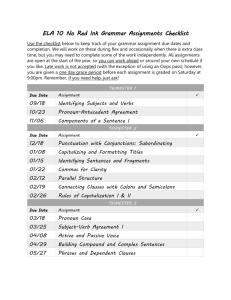

10 Tips for Teaching Grammar

According to the Common Core

T

he Common Core State Standards stress the importance of teaching grammar. The standards lay out which

grammar rules should be taught at which grade levels. So you know what rules to teach… but how do you

teach them? Here are ten tips for teaching grammar according to the Common Core. (See the infographic

on page 21.)

1.Teach grammar in the context of writing.

Grammar shouldn’t be taught as a separate, isolated unit. Think of ways to incorporate grammar minilessons into your writing lessons. You may be doing this already. For example, in grade 7, students

are expected to correct misplaced and dangling modifiers (Language Standard 1c). Don’t just have

students practice with a bunch of random workbook sentences; have students check their own

use of modifiers in an essay they’re writing. And remind students that knowing grammar is not only

about making corrections; it is also about creating style. The CCSS state that students should “come to

appreciate that language is at least as much a matter of craft as of rules” (CCSS, p. 51). In Big Skills for

the Common Core, Benjamin and Hugelmeyer give this example: If you’re teaching coordinating and

subordinating conjunctions (grade 5), don’t just show students how they function in a sentence. Show

students how they can improve your writing by combining sentences to strengthen relationships and

by creating sentence variety. Grammar gives you tools to create your own writing style.

2.Teach grammar in the context of reading.

Use mentor texts. Show students how fiction and nonfiction writers use grammar to communicate

clearly and to create their own style. Have students find examples of a grammar rule, such as parallel

structure, in a text they are reading.

3.Help students figure out the grammar rule; don’t just give it to them to memorize.

For example, if you’re teaching concise language, give students a few wordy sentences and ask them

to remove the weeds from those sentences. Then ask students to come up with some general rules for

eliminating the wordiness from their writing. That approach can be more effective than starting with

the rules (e.g., “Eliminate wordiness by doing this, this, and this.”).

4.Teach students real-world grammar and not just textbook grammar.

In the real world, grammar rules can change over time and can be subjective or contested. In

grades 11–12, students are expected to “resolve issues of complex or contested usage, consulting

19

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

references… as needed” (Language Standard 1b). The serial comma is an example of grammar rule that

is contested. Some publications use the serial comma (also known as the Oxford comma) and some do

not. (We like it here at Eye On Education!)

5.Don’t just teach students grammar; teach them how to learn grammar.

The Common Core requires students to use reference materials. Students need to know how to be

independent learners who can figure things out on their own. After all, they won’t always have a

teacher telling them which part of speech to use.

6.Show students how grammar helps us communicate more clearly.

Give examples of how incorrect grammar can lead to miscommunication. Students will be more

motivated to learn grammar when they see its importance.

7.Show students how grammar can affect our impression of one another.

Have a discussion with students about grammar in the real world. If a fancy store has a mistake on its

sign, does the mistake affect your impression of the store? Why or why not?

8.Avoid negative modeling when possible.

Be careful not to spend too much time on the wrong way to write something. If you flood your

whiteboard with incorrect sentences (e.g., “Jessica and me went to the movies”), those sentences might

start sticking in students’ heads more, even though your intention was to break students of the habit.

9.Teach students the rules—and when to break them.

For example, sometimes it’s okay to end a sentence with a preposition. In some cases, adhering to a

grammar rule can make you sound stuffy or silly. As Churchill famously said, “There is some nonsense

up with which I will not put!” (My sixth-grade students loved that example.) Common Core Literacy

Lesson Plans (http://bit.ly/Zm8IGH) has another example of breaking the rules: Active voice is usually

preferred, but in scientific writing, you may want to use passive voice. That’s because in science,

sometimes the action is more important than the subject (e.g., “The chemical was added to the

mixture”).

10.Teach students the importance of audience and purpose when making language decisions.

Students need to make decisions about when to use formal or informal grammar. They should

consider audience and purpose. The CCSS require that students learn to apply grammar in increasingly

sophisticated contexts.

This post was originally published on December 19, 2012.

20

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

21

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.

The Common Core Made Easy

A Collection of Tips, Resources, and Ideas

About the Author

Lauren Davis has been Senior Editor at Eye On

Education since May 2011. She is the author of the

popular white paper “5 Things Every Teacher Should Be

Doing to Meet the Common Core State Standards,” and

presented a well-attended webinar on the same topic in

May 2012.

Lauren is a regular blogger on Eye On Education’s blog

and writes a bi-monthly column called Comments on the

Common Core, which began in August 2012. Lauren was

one of three judges for Education World’s Community

Lesson Plan Contest and she recently published a blog

post for SmartBlog on Education called “Should I Teach

Problem-, Project-, or Inquiry-Based Learning?”

Previously, Lauren served as Senior Editor of Weekly

Reader’s Current Events, a classroom news magazine

for students in grades 6-12. She also spent five years as

Director of Language Arts at Amsco School Publications,

a publisher of workbooks and other resources for

secondary students.

Lauren began her career in the classroom. She taught sixth-grade ELA in Westchester, NY, and

she also taught seventh- and eleventh-grade English in New York City. She is passionate about

engaging students in learning. Her book series, Common Core Literacy Lesson Plans: Ready-to-Use

Resources (http://bit.ly/Zm8IGH), was published by Eye On Education in September 2012.

For information about permission to reproduce and distribute this eBook, please contact

Toby Gruber, Director, Professional Services, Eye On Education, at (914) 308-0520 or

tgruber@eyeoneducation.com.

22

Copyright © 2013 Eye On Education, Inc. Larchmont, NY. All rights reserved, www.eyeonducation.com.