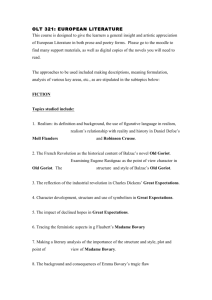

TUSSLING WITH FLAUBERT.wps

advertisement