Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption

advertisement

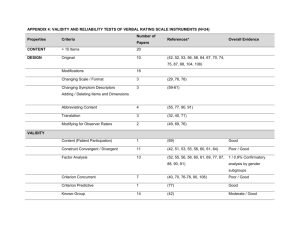

Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol Arthur Guerra de Andrade Lúcio Garcia de Oliveira INTRODUCTION From social to problematic use, alcohol is consumed by approximately 2 billion people.1,2 This consumption can be understood through multiple perspectives. For example, from the public health point of view the consumption of alcohol is a potential agent of sickness and mortality. The improper use of alcohol is responsible, worldwide, for 3.2% of all deaths and 4% of loss of the Disease Adjusted Life Years (DALY).3,4 In recent years, scientific evidence has indicated the importance of knowing alcohol use patterns. Depending on the pattern, alcohol can elevate the risk in developing health, family and occupational problems, among others. Along with the total volume of alcohol consumed, the relevance of knowing the pattern of consumption as an indicator of problems has been widely discussed.4 On the other hand, some studies have reported that the pattern of use, especially moderate use, can be beneficial, especially in regards to the development of cardiovascular diseases.2-6 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts The definition of a pattern of consumption is multidimensional, and includes within the context of drinking; the cultural relevance, the choice of drink, the frequency of consumption (number of days per week), the quantity, the place (i.e. at home, in a bar, in a restaurant etc.), whether it is consumed during meals or not and finally, the individual characteristics of the drinker, whether biological, genetic, socio-demographic or socio-economic.5 Aside from these, another factor of interference is the quality of the alcoholic beverage, which serves as a measurement for future problems due to the consumption of alcohol. All of these factors, considered together, influence the resulting implications of the drinking behavior, which will be briefly broached in this chapter. The exact definition of different patterns of alcohol use makes the localization of real limits possible – the damages and benefits commonly associated with the consumption of alcohol. Unfortunately, its importance is still underestimated and, for this reason, the investigation of pattern of consumption has not been included in epidemiological surveys.7 Within the patterns of consumption much has been said about moderate use in a preventive and beneficial role for some chronic sicknesses like cardiovascular diseases, type II diabetes, cognitive functioning, among others. CONCEPTUALIZATION OF THE TERM MODERATE USE International definition by the WHO and by NIAAA According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “moderate use” is an inaccurate term that defines a pattern of consumption in which quantities of alcohol are used without provoking health problems. Many times, moderate use is employed as a synonym of social drinking and defined as non-problematic; this way of drinking and its motivation are socially accepted according to the habits. Many countries offer guidelines concerning consumption levels that are considered safe, responsible or low-risk, generally defined in a clear way, by government entities and non-governmental organizations (NGO). These guidelines do not recommend the consumption of alcohol by minors or pregnant 36 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol women. However, for people who are in medical treatment which could be altered by alcohol consumption, or for those who have a medical history related to problems with the use of alcoholic beverages drinking should not be recommended. Generally, these guidelines define the quantity of pure ethanol in a standard unit of alcohol (different in every country) and offer advice to the special populations which are at risk. According to these guidelines, especially the ones that refer to standard units, one unit of alcohol generally contains from 8 to 14 grams (g) of pure ethanol (Table 1); among which Japan stands out, reaching almost 20 g. In general terms, this variation shows that there is no international consensus about the exact dimension of a standard unit for an alcoholic beverage. But, according to the guidelines, moderate use has been considered a level or a pattern of use in which there is less damage and an increase in health benefits, in which the influences of gender and age of the drinker have been considered. Due to of physiological differences, the levels of consumption considered moderate are greater in men up to 65 years old, and less for older individuals. In the United States, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) uses the term moderate use to refer to consumption which will not cause individual damage to the drinker, nor cause social problems. In terms of drinking units, moderate use is defined as the use of up to 14 g units per week for men, up to 7 g per week for women and no more than 1 g per week for individuals over 65 years of age (with the standard unit being 14 g of pure ethanol). Abstinence for one or two days per week is advised. For daily levels, this consumption can be translated into two alcoholic units for men (28 g) and one for women (14 g). In addition to this, the definition of moderate consumption in terms of daily units, is not absolute, with a variation from one to five doses per day.8 Even though the levels stipulated by the NIAAA are reasonably similar to the ones suggested by other countries, the exact definition of moderate use is still controversial,6,8 especially due to the variation of the definition of a standard unit. In contrast, it has been observed that some countries define moderate 37 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts consumption without defining a standard unit. Thus, the concept of moderate use varies not only among countries, but also within each country. For example, France and the United Kingdom recommend, in terms of consumption of daily alcoholic units, quantities of alcohol greater than to the ones suggested by the United States, recommending three and from three to four daily alcoholic units, respectively. In countries such as Australia, Spain and Portugal the greatest quantities of alcohol in the definition of moderate consumption are found, reaching 42 g of alcohol daily. There are countries in which moderate use is defined for specific beverages, as in Romania (beer and wine); or where the definition in daily terms is correlated to sex (i.e. Canada, Romania, Sweden and Switzerland). There are countries that simply recommend the reduction or avoidance from consumption, without clearly definition what the moderated use is (i.e. Indonesia, Luxembourg, Thailand and Saudi Arabia). The NIAAA indicates that the difficulties related to the definition of moderate use are, to a certain point, the result of individual differences, since the quantity of alcohol that a person can consume without being intoxicated varies depending on experience, tolerance, metabolism, genetic vulnerability, lifestyle, and period of time in which the consumption is realized (three doses in one hour, for example, produce an alcohol concentration in the blood much higher than three doses over three hours).8 Finally, there are countries which, even with the absence of official definitions about moderate consumption, adopt international recommendations suggested by the WHO9, as in: •• women should not drink more than two daily units of alcohol; •• men should not drink more than three daily units of alcohol; •• drinking should be kept to the minimum possible, and the abstinence from alcohol should be taken for two days a week; •• in special situations there should be no consumption. For example, during pregnancy, while driving a motor vehicle, during work (especially when operating 38 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol machines), while exercising, and if someone is already alcohol dependent, or has other physical problems which would be aggravated while drinking. The differences related to the definition of moderate consumption among countries are illustrated in Table 1. Table 1 DEFINITION DIFFERENCES OF MODERATE CONSUMPTION AMONG COUNTRIES­ Country Unit / standard drink Recommended guidelines for adult ‘low risk’ consumption – maximum levels in grams of alcohol Argentina N/A Some information via: www.vivamosreponsablemente. com Australia 10 g Men: Max. 4 drinks/day - 6 drinks on any occasion Women: Max. 2 drinks/day - 4 drinks on any one day One or two alcohol-free days every week Source: National Health and Medical Research Council (NMRMC): www.nhmrc.gov.au and Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing: www.alcohol. gov.au www.drinkwise.com.au Austria 10 g Men: 24 g/day Hazardous drinking: 60 g/day Women: 16 g/day Hazardous drinking: 40 g/day Source: Federal Ministry for Labour, Health and Social Affairs: www.bmsg.gv.at Belgium N/A There are no governmental guidelines Canada 13,6 g Men: 2 units/day, max. 14 units/week Women: 2 units/day, max. 9 units/week Source: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health: www. camh.net and www.educalcool.qc.ca Czech Republic N/A Men: 24 g/day Women: 16 g/day Source: National Institute of Public Health: www.szu.cz and www.forum-psr.cz Denmark 12 g Men: 21 units/week Women: 14 units/week Source: National Board of Health: www.sst.dk and www.goda.dk (continue) 39 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts Table 1 (Cont.) DEFINITION DIFFERENCES OF MODERATE CONSUMPTION AMONG COUNTRIES Country Unit / standard drink Recommended guidelines for adult ‘low risk’ consumption – maximum levels in grams of alcohol Finland 11 g Men: 15 units/week Women: 10 units/week Source: www.alto.fi France 10 g Men: 3 units/day Women: 2 units/day Source: WHO International Guidelines Cited by the Source: Health Ministry: www.2340.fr Germany 12 g Men: 3 units/day Women: 2 units/day Source: www.drinkingandyou.com Greece 10 g Men: 3 units/day Women: 2 units/day Source: Ministry of Health Hong Kong Defined as “a drink” Hungary N/A Responsible drinking info via: www.hafrac.com Indonesia N/A Avoid drinking alcoholic beverages Source: Ministry of Health Dietary Guideline State and the National Dietary Guidelines Iceland N/A Pregnant women are advise to abstain while pregnant or if breast feeding. Source: Alcohol and Drug Abuse Prevention Council Ireland 10 g Men: 21 units/week Women: 14 units/week Source: www.drinkaware.ie Italy 12 g Men: 2-3 units/day Women: 1-2 units/day Source: Ministry of Health: www.alcol.net Japan 19.75 g Men: 3 units/day, max. 21units/week Women: 2-3 units/day, max. 14 units/day Men: 1-2 units/day Women: N/A Source: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (continue) 40 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol Table 1 (Cont.) DEFINITION DIFFERENCES OF MODERATE CONSUMPTION AMONG COUNTRIES Country Unit / standard drink Luxembourg N/A Moderate consumption is promoted without a precise definition Malta N/A Responsible drinking guidelines: www,thesengroup.org Mexico Recommended guidelines for adult ‘low risk’ consumption – maximum levels in grams of alcohol Responsible drinking advice: www.alcoholinformante. org.mex The Netherlands 10 g Men: 4 units/day Women: 2 units/day Source: www.stiva.nl and www.alcoholinfo.nl New Zealand 10 g Men: 3 units/day, max. 21 units/week Women: 2 units/day, max. 14 units/week Source: Alcohol Liquor Advisory Council www.alcohol. org.nz Norway N/A Visit: www.alkokutt.no Poland 10 g Men: 2 units/day Women: 1 unit/day Two alcohol free days per week recommended Source: Parpa www.parpa.pl Portugal 14 g Men: 2-3 units/day Women: 1-2 units/day Source: National Council on Food and Nutrition Romania N/A Men: 32.4 g of beer or 20.7 g of wine/day Women 32.5 g of beer or 20.7 g of wine/day Source: Ministry of Health Singapore N/A Limit alcohol intake to not more than two standard drinks a day (about 30 g alcohol) Source: Ministry of Healthy National Dietary Guidelines Slovenia N/A Men: 20 g/day, max. 50 g on any occasion Women: 10 g/day, max. 30 g on any occasion Source: Institute of Public Health South Africa N/A Men: Max. 21 units/week Women: Max. 14 units/week Source: www.ara.co.za (continue) 41 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts Table 1 (Cont.) DEFINITION DIFFERENCES OF MODERATE CONSUMPTION AMONG COUNTRIES Country Unit / standard drink Recommended guidelines for adult ‘low risk’ consumption – maximum levels in grams of alcohol Spain 10 g Men: Max. 40 g/day Women: Max. 24 g/day Source: Ministry of Healthy National Plan On Drugs www. alcoholysociedad.org Sweden N/A Men: Max. 20 g/day Women: Max 20 g/day Source: Swedish Research Council www.vr.se Switzerland 10-12 g Taiwan N/A Responsible drinking. Source: www.tfbaf.org.tw Thailand N/A Avoid or reduce the consumption of alcoholic beverages Source: Ministry of Public Health United Arab Emirates N/A No official guidelines. Alcohol available in hotels to guests and visitors. Expatriate residents must posses a liquor permit. Retail outlets sell only to permit holders for personal consumption. Providing alcohol to others is forbidden United Kingdom 8g Men: 3-4 units/day, max. 21 units/week Women: 2-3 units/day, max. 14 units/week Sources: Department of Health: www.units.nhs.uk and www.drinkingandyou.com USA 14 g Men: 2 drinks/day, max. 14 units/week Women: 1 drink/day, max. 7 units/week Department of Agriculture & Department of Health & Human Services; www.healthierus.gov/dietaryguidelines and www.whatsadrink.com Men: 2 units/day Women: 2 units/day Source: Swiss Federal Commission for Alcohol Problems Source: Drinking & You.10 N/A = Not applicable. Definition of moderate use of alcohol in Brazil There is no definition of moderate use in Brazil. Statistical surveys about the consumption of alcohol (Residential Surveys I and II about the Use of Psychotropic 42 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol Drugs) were done in 108 Brazilian cities with populations above 200,000 inhabitants11,12 with both general and specific populations, such as elementary and high school students, adolescents and street kids.13,14 The survey referred only to the prevalence of the use of alcohol (lifetime use, per month and per year), not mentioning the pattern of consumption. The First National Survey about the patterns of consumption of alcohol in the Brazilian population15 analyzed how Brazilian adults drink. Combining the variables of frequency and quantity of use, categories were identified and described by the intensity of drinking; frequent heavy drinker, frequent drinker, less frequent drinker, not frequent drinker and abstainer. Moderate use is not mentioned or identified in the proposed categories, since a consumption of five daily doses of alcohol was adopted as a limit. In another epidemiologic survey done in the state of São Paulo, a representative sample using different age groups, socio-economic conditions and education was adopted (part of GENACIS – Alcohol, Gender and Drinking Problems: Perspective of low and middle income countries, study by the World Health Organization (WHO), and was one of the few Brazilian surveys which defined and investigated, similar to the international standards, the term moderate use. This study defined moderate use as the consumption of only three alcoholic doses, less than four per occasion, on a weekly basis or more frequently (in the last 12 months). In spite of this definition, the prevalence was very low, corresponding to 7% of the sample studied.16 Generally thinking, it is perceived that even though the term moderate use or moderated use is frequently adopted principally in public announcements about alcoholic beverages, there is not an exact Brazilian definition that follows the recommendations proposed by WHO and by NIAAA. Public Opinion about moderate use in Brazil and in the world The lack of an international standard about the moderate use of alcohol is reflected in the larger community, as the definition is difficult for the general 43 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts public to understand. Having conflicting, and often false information increases the chances for the public to assume a risky behavior of drinking, exposing themselves to negative relevant implications, either short, medium or long-term. For example, according to a Canadian survey, 57% of the subjects interviewed considered that moderate consumption was beneficial to their health17. A North American survey, which was devoted to the study of public opinion about the moderate use of alcohol, indicated that this behavior was associated with the false idea of control, state in which a person is not drunk and there is an absence of short-term negative consequences, with variations in the type of drink and the setting or context of use. Others believed that moderate consumption does not exist or it was equal between men and women.18 Yet, in general, the beneficial point of view on moderate use has been more prevalent among men in the age group over 45. They are frequent drinkers, who could be looking for an incentive, and in this belief, there is a kind of stimulus or an excuse for consumption.17 In Brazil, even though there are no direct studies which deal directly with the popular perception of moderate use, 80% of the people accept social drinking and weekly drinking of one to two doses of alcohol – an opinion especially common among male youths between 18 and 34 years old. This acceptance stands out more when considering that 93.5% of the Brazilian population judges the daily use of alcohol as a serious health risk.12 Altogether, these data indicate that there is a necessity for competent public organizations to define and communicate to the population in an objective, clear and transparent way what moderate use is, minimizing confusion and consequently, the risks and dangers associated with this pattern of consumption. ASSOCIATED PROBLEMS From moderate use to abuse/ dependence Initially, the consumption of alcohol can happen in a search for relaxation or to decrease stress and anxiety, mainly in social leisure and entertainment situations. The NIAAA report alerts that people who do not drink or that are 44 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol moderate users can become alcoholics if they increase their consumption of alcoholic beverages. A low estimate predicts that 5% to 7% of people who do not consume alcohol or use it sporadically can have problems as a result of its consumption.8 In Brazil, 52% of the citizens drink, while the other 48% are abstinent, have either never drunk, or have consumed alcohol less than once a year. Regarding the consequences associated with consumption, 12% of the Brazilian population reported that they have already had an associated problem, among which 3% are heavy users and 9%, especially men, are alcohol dependent, a difference that is up to four times greater than the prevalence detected in women.15 In greater detail, about 30 million Brazilians have already had at least one problem related to the use of alcohol during their lives. The prevalence of drinkers with problems seems to decrease with age, going from 53% in the age group of 18 to 24 years old, to 35% in over the age group over 60 years old. Among the problems mentioned, physical ones are more common, followed by family and social conflicts (with some episodes of violence), work, and legal problems, among others.15 Once a harmful pattern of consumption is developed, it can either lead to the drinkers maintaining their drinking habits for decades without developing dependence, or they return to a problem-free pattern of ingestion. This last situation is rarer, especially when the measure of severe dependence increases.19 The therapeutic response to alcoholism has a very low – only 1% of the patients who recognize a developing alcoholic problematic habit look for help and have a chance of being evaluated, diagnosed and motivated for the treatment, and consequently reach the state of abstinence. However, independent of all of the possible profiles of patients, there is still belief in the “Law of the Third”, which means that in the treatment of alcoholics 1/3 recover, 1/3 present no significant alteration and 1/3 get worse.19 In addition to the low therapeutic response, there is evidence that the consumption of alcohol is beginning considerably earlier, making adolescents and young adults more vulnerable to the problems and the consequences 45 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts associated with alcoholic consumption. In Brazil, at the age of 13.9, adolescents report that they have already tried alcohol and regular consumption begins around 14.6 years old15. In a Brazilian statistical survey done with 48,155 elementary and high school students, 65.2% of the interviewees said that they had already consumed alcohol, with the greater number of them belonging to the age group between 13 and 15 years old (61.7%). Besides this, 11.7% of the adolescents say that they are frequent consumers and 6.7% affirm that they are heavy consumers, or have consumed alcohol 20 or more times in the 30 days before the interview.13 Aside from the early use of alcohol facilitating the development of abusive use and dependence, minors have the tendency to expose themselves to risky situations, such as early sexual activity, the practice of unsafe sex (without protection), the existence of multiple sexual partners, unwanted pregnancies, getting drunk and trying other drugs. This is due to the difficulty of assessing the risk of the situation, since the individual is under the effect of alcohol, and it can also influence the choice of peers and situations which favor them.20 It is believed that the postponement to the introduction of the use of alcohol could be a relevant factor of protection against being exposed to risky situations and consequently, reduce health system costs due to alcohol, suggesting the importance of the early implementation of prevention programs during adolescence.­ Association of alcohol with other drugs Many times, alcohol is consumed simultaneously with other psychotropic substances, especially tobacco and marijuana, even though the alcohol-medicine association (analgesics, stimulants, sedatives or tranquilizers) is largely mentioned, mainly among adolescents and university students.21,22 The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) is a survey which investigated this type of association among adolescents, in the age group between 15 to 18 years old, from 39 European nations.22 46 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol An example of this type of association is the simultaneous consumption of alcohol and tobacco. A North American survey conducted with 1,113 university students from 18 to 24 years old, observed that there is a positive relation between these uses, in a manner that any quantity of tobacco used would be, in some form, related to the consumption of alcohol. Due to the fact that the use of tobacco increases during the consumption of alcoholic beverages, it is believed that alcohol stimulates this use, besides deviating the attention of the user over the consumption. More than quantity, the frequency that alcohol is used is a strong leading factor in the consumption of tobacco, and is associated with the use of illegal drugs and the recreational use of medicine.23 Independently of the substance which alcohol is associated with, this type of consumption is very dangerous because, besides predisposition to toxic reactions of relevance by the user, the chances of developing abuse or dependence to associated drugs are increased and damages cognitive function, capacity to reason, analysis, judgment and predisposition of the individual to physical, emotional and socially risky behaviors.21,24-26 Health Problems Health problems are among the main consequences related to the use of alcohol, considered the cause of more than 60 types of diseases4 of acute or chronic development, contributing to around 4% of all worldwide cases of diseases and creating a significant cost for healthcare system.27 The diseases associated with the consumption of alcohol can be grouped in three categories, reflecting the nature of their conditions and the etiological consumption of alcohol7: •• health conditions fully attributed to the use of alcohol (100% of causality relation): neuropsychiatric perturbations, alcoholic psychoses, abuse and dependence of alcohol, fetal conditions and hepatic cirrhosis, and others; •• chronic conditions in which alcohol is the contributing factor: mouth, orthopharynx and breast cancer, miscarriage, and others; 47 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts •• serious conditions in which alcohol is the contributing factor: automobile accidents, falls, poisoning, drowning, homicide, suicide, and others. The last category can be subdivided into non-intentional situations, as in automobile accidents and falls, and intentional, as in self-harm, homicides and suicides.4 All of the fetal conditions caused by the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy are denominated the spectrum of fetal alcoholic disturbances. Among these disturbances, in the most common cited is the fetal alcoholic syndrome (FAS). The moderate consumption of alcohol has been especially harmful in cancer, hepatic diseases and pregnancy situations, described as follows. Cancer The consumption of alcohol worldwide is responsible for the incidence of 5.2% of the cases of cancer in men and 1.7% of the cases in women, a development which occurs on a long term basis.28 It is estimated that 60% of the incidence of cancer, especially in women, associated with the use of alcohol has occurred in the form of breast cancer.29 There is strong evidence of an association with the use of alcohol and the incidence of cancer in the upper digestive system (oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus and larynx), but the magnitude of the relation to the incidence of anal, colon and liver cancers is still controversial.30 Although the consumption of alcohol is positively related to a considerable group of cancer cases, little is known about the relationship between moderate use and incidences of cancer. A change in the pattern of consumption, from heavy to moderate, has little influence in cancers development, but on the other hand, if an abstainer began a moderate use of alcohol, the incidence of cancer would increase in an excessive manner.31 The relationship between a pattern of moderate use of alcohol and the incidence of cancer as well as with its related cause is still controversial, and further research is necessary for a complete understanding. 48 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol Hepatic diseases The abuse of alcohol is the greatest factor in death caused by hepatic diseases in the United States, and 40% to 90% of those deaths are from hepatic cirrhosis.8 There is a parallel between the quantity of alcohol consumed (and the history of its use) and the incidence of hepatic diseases. Among the patterns of consumption moderate use of alcohol is not beneficial to hepatic diseases, and causing the disease in susceptible individuals32. Even though it is not known for sure the alcoholic dosage level responsible for these diseases, studies suggest that 14 weekly alcoholic doses for men and seven weekly doses for women can lead to the occurrence of hepatic diseases. However, other studies, suggest higher doses. The NIAAA report suggests that hepatic cirrhosis is generally associated with the consumption of five daily doses of alcohol for a period of at least 5 years.8 The presence of other hepatic diseases, especially hepatitis B and C, significantly increases the risk of hepatic damage when combined with the moderate or excessive consumption of alcohol.33 Obesity and the exposure to drugs and other substances associated with the consumption of alcohol also present additional risks in the development of hepatic diseases.34 Due to these multiple interfering factors safe levels of alcohol consumption in relation to hepatic diseases varies significantly from individual to individual. Pregnancy A North American population survey indicated that 30.3% of 4,088 pregnant women declared that they had consumed alcohol during pregnancy. During this interval, the pattern of consumption seemed to vary depending on their socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics, such as age group, level of education, social economical class, ethnic group, intention of getting pregnant, use of tobacco during pregnancy, alcoholic use before pregnancy, and finally, history of use of alcohol on a binge standard (defined as more than four alcoholic doses in one occasion of consumption) in the 3 months prior to conception. 49 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts According to these authors, in the pre-gestational period women who had drunk on a binge were eight times more likely to drink during pregnancy and 36 times more likely to go on a binge during pregnancy.35 Aside from the previously outlined factors, a study done with pregnant women attended by an obstetrical service of the Socialized Health System (SHS) in the city of Ribeirao Preto, Sao Paulo, indicated that the exaggerated consumption of alcohol during pregnancy could reflect a lack of structure in the emotional state of these women (i.e. anxiety and depression).36 Independent of the underlying reasons, the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy has teratogenic effects, which cause a series of cognitive, behavioral and neurological damages. The continuum of disorders which follow this consumption is known as fetal alcoholic syndrome disturbance (FASD), of which the most commonly studied is the fetal alcoholic syndrome (FAS). Studies have indicated that children and adolescents with FASD present serious encephalic structural modifications, suggesting a deficit in the development and the healthy organization of the nervous system37, which could be the basis of an incidence in commonly reported cognitive, emotional and psychiatric deficits.37,38 In the specter of anomalies caused by the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy, FAS is an evident characteristic, presented by irreversible neurological damages, delayed growth and body malformations, especially in the face. Cognitively, children exposed to the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy are more impulsive and present attention and memory deficit – disturbances that are more evident in children whose progenitors were heavy consumers of alcohol during pregnancy.38 In the same manner, this standard of alcohol consumption during pregnancy increases the risk of developing psychiatric diseases in the adult phase, such as personality disorders or disorders related to the use of alcohol or other substances.39,40 Although it is known that the consumption of alcohol negatively effects the fetus, it is still not known for sure the minimum dose which causes this type of problem. It is believed that FAS, for example, can attack any population, even with moderate consumption or small quantities of alcohol during pregnancy41. 50 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol Another survey that investigated 501 women whose children presented behaviorial problems indicated that only one weekly dose of alcohol was sufficient to cause a behavioral alteration in childhood. According to this survey children who are exposed to alcohol are 3.2 times more likely to present aggressiveness compared to those that are not exposed.42 In spite of the results of many surveys, there is not any conclusion regarding a quantity of alcohol which can be consumed safely during pregnancy. Since there are no secure limits, a pregnancy would only be considered secure if it were completely free of alcohol, suggesting that pregnant women should be alcohol abstinent. For this question to be answered, it is important that public authorities invest in measures of prevention which identify and reduce the exposure of alcohol during pregnancy. Another possible measure would be to counsel sexually active and childbearing age women about the use of reliable contraceptive methods, planning the pregnancy and interrupting of the consumption of alcohol before pregnancy. ASSOCIATED BENEFITS Since the early 1990s numerous scientific epidemiological studies (prospective and case controlled) of clinical intervention or experimental based models have mentioned the relationship between moderate use of alcohol and the incidence and progression of chronic diseases, in which gender, type of beverage and confounding factors (social and demographical) must be considered. Thus, moderate consumption of alcohol has been associated with a decrease in mortality rates, which suggests a possible beneficial effect on health with this use.43,44 Many authors who focus their studies on the comprehension of the health effects of moderate alcohol use describe this relation graphically, by a “J” curve43,45,46, in which the benefits of alcohol use (in this case, the decrease of the death rate) are possible until a certain point, and from this point on the consumption of alcohol becomes damaging. 51 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts The beneficial effect of the moderate use of alcohol in the incidence and/or development of some diseases, especially in relation to some cardiovascular diseases, will be described in this section. Cardiovascular diseases There is not a consensus regarding the contribution of alcohol use in the development of cardiovascular events, especially because drinking lightly or moderately has favorable effects, while unfavorable effects are attributed to heavy drinking. In what is referred to as moderate use, Klatsky et al47 was the first to suggest the existence of an inverse association between this use and the risk of developing cardiovascular events, illustrated in the graph by a “U” or a “J” curve.45 Although this association is clear when considering the development of coronary diseases, the relationship with the development of other cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular events (i.e. cardiomyopathy, hypertension, arrhythmia, hemorrhagic and ischemic brain stroke, and congestive cardiac insufficiency) is still controversial, and seems to change depending on the type of event. Recently, a revision about the effects of alcohol consumption on the incidence of cardiovascular events indicated a disparity of action6, briefly mentioned and divided by the type of cardiovascular event. Myocardiopathy This is a term that refers to a disease of the striated cardiac muscle. The most common type is dilated myocardiopathy, in which there is an increase in the dimension of the heart and a decrease in its propulsion strength. It is believed that the chronic and heavy use of alcohol can cause this disease, although lighter standards of consumption can also cause it, especially when associated with co-factors such as the deficiency of thiamin (Vitamin B1), genetic factors, and viral infection. 52 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol Hypertension Although the exact biological mechanism of alcohol’s influence has not been proposed, heavy use increases the risk of developing hypertension, independent of nutritional factors – a relationship that has not been found in light and moderate users. Aside from that, the heavy use of alcohol interferes with medical treatment, while moderate use or abstention improve the results of non-pharmacological interventions aimed at decreasing blood pressure (i.e. weight loss, physical exercise and the restricted use of salt). In general terms, some studies have suggested a graphic relation, in the form of a “J”, to identify the interference of the use of alcohol on blood pressure, in which light drinkers have a modest reduction in blood pressure levels.48 Arrhythmia The risk of developing arrhythmia is greater among heavy consumers of alcohol, while it has not been observed in light and moderate consumers. This increase possibly occurs because of damages to the myocardium, the effects of alcohol on the vagal reflex, on the conduction of nervous impulses and of refractory time and the possible influences on the roles of catecholamine and acetaldehyde. The Holiday Heart syndrome is one of the well-known arrhythmias, which is a consequence of strongly abusing alcohol. Stroke Various studies have suggested that the heavy use of alcohol, as in going on a binge, is associated with an elevated risk of incidence of cerebral hemorrhage. Nevertheless, few studies have indicated the interference of alcohol in accordance with the type of stroke, whether hemorrhagic (by rupture of the blood veins) or ischemic (by occlusion). Other studies indicate that heavy users are more likely to develop a hemorrhagic stroke, although the risk of ischemic stroke from alcohol use is still not completely explained. 53 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts Coronary diseases Epidemiological studies have demonstrated a reduction in mortality rates by acute myocardial heart attack and coronary diseases in moderate drinkers, which indicates the cardioprotective effect of alcohol and what type of drink is a relevant factor. Although this effect has been observed in the most common types of beverages (wine, beer and distilled), it seems to be more prevalent with wine drinkers and less in individuals who consume distilled beverages. A significant difference between red and white wine is not made. Aside from this, the beneficial effects of alcohol are influenced by the pattern of use and by the personal characteristics of the drinker. Heart failure This is a syndrome functionally described by a situation in which cardiac function is inadequate to attend to the real needs of the body, creating a clinical diagnosis corresponding to congestive cardiac insufficiency, which can become complicated with the development of acute edema of the lung and cardiogenic shock. In this situation, the most common standard is the dilated myocardiopathy. The risk of heart failure increased in heavy consumers of alcohol. Aside from decreasing the incidence of cardiovascular diseases, there is scientific evidence that moderate consumption can reduce the risk of its progression in individuals who already present it, as well as in coronary disease patients. Then, comparing with abstaining individuals, the light and moderate use could reduce the risk of cardiovascular events occurring in subjects with high blood pressure, diabetes, and other cardiac diseases.49,50 The beneficial effects of moderate consumption of alcohol extend to other conditions such as type II diabetes, cognitive function, cardioprotective factors and types of beverage. 54 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol Type II Diabetes Nowadays, a world epidemic of obesity and diabetes mellitus has been witnessed, and the main factors responsible for it are the exaggerated consumption of food and lack of physical activity. Although heavy drinking is associated with high levels of glucose and poor adherence to the control of diabetes, moderate drinking has been associated with a lower risk of development of diabetes with beneficial effects in glucose metabolism and on insulin levels. A meta-analysis of 15 cohort studies indicated the existence of a relation, graphically represented by a “U” curve, between the consumption of alcohol and the development of diabetes type II, with a 30% to 40% reduction of risk for consumers of one to two daily doses of alcohol when compared with abstaining individuals, both men and women.44,49 Moderate use presents more favorable effects and the type of alcoholic beverage seems to have little influence on this risk.51 The exact action mechanisms of moderate alcohol consumption in type II diabetes are not fully understood, but it is possibly from the increase of cellular sensitivity to insulin52 or the decrease in intolerance to glucose – hypotheses that have yet to be proven. Cognitive functioning Abusive and prolonged use of alcohol is associated with the occurrence of dementia. Dementia is the most common disorder which affects the elderly, of which the relevant factors are gender, education, diet, and vascular issues. The two most common types of dementia in the western population are Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia. Regarding the effect of alcohol, especially on the cognitive function of the drinker, prospective studies have indicated that there is an association between the moderate use of alcohol and the decreased risk of developing dementia53,54 compared to the inherent risk for non drinkers or abstainers. In addition to this, when the influence of gender is considered, the risk seems to be lower for men even though the amount of 55 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts alcohol ingested is equal.55 However, the influence of gender on cognitive function is still controversial, since there are studies which affirm exactly the opposite.56,57 Thus, a study which evaluated the mental function of 12,480 women with ages between 70 and 81 years old, who consumed up to 15 g daily of alcohol, showed that these women presented a better performance in cognitive evaluation than the abstainers, and maintained a better performance even 2 years after the first evaluation.56 If the type of beverage is considered, the consumption of wine diminishes the risk of dementia, while the use of beer and distilled drinks seems to increase it – a relationship that is still controversial.58 The mechanisms of alcoholic influence on the risk of dementia seem to be secondary to the decrease of risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, the possible improvement of the cholinergic neurotransmission in the region referring to the hippocampus as well as to the inherent antioxidant effect of alcohol, among others.59 Cardioprotective factors The cardioprotective properties of moderate use are being continually studied.44 In model experiments, distinct biological mechanisms have been suggested and described to explain the beneficial effects of alcohol, among which changes of plasmatic profile of the lipids stand out, especially regarding the increased levels of high density level cholesterol (HDL) and its subtypes. These results have been corroborated by studies that analyze the cardioprotecive factors on the incidence of coronary diseases, pointing out different mechanisms: •• increased level of plasmatic HDL, especially of the subtypes HDL2 and HDL3, which would make possible a reduction of the accumulated cholesterol in the walls of the blood vessels and the decrease of oxidation of LDL (low-density lipoprotein); •• decrease of blood coagulation mechanisms; •• reduction of stress or anxiolytic effects5,6. 56 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol However, the joint action of changes in vascular, myocardial, hemostatic and endothelial functions seem to contribute to the reduction of the global risk of the incidence of cardiovascular events, including the decrease of platelet aggregation, inflammation, and a series of other factors.60 Light to moderate use of alcohol, though, depending on the cardiovascular events, can be measured by other effects. A good example is that the effect of alcohol consumption on arterial pressure, especially high blood pressure, ends up controlling one of the risk factors of greatest relevance in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases. Interference of type of beverage It is important to notice that the beneficial effects of moderate consumption of alcohol on health, especially in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases, is not generalized, since it varies depending on the type of beverage. One of the first investigations on this theme suggests that the incidence of coronary diseases was less prevalent in countries where wine is traditionally consumed than in those where beer or distilled beverages were consumed.61 Currently, the cardioprotective effect with the moderate use of wine is noticeable and scientifically proven, while the effect of beer or distilled beverages is still controversial, in such a way that it is still difficult to reach a consensus.62,63 More than the effects of the beverage, per se, it is suggested that the pattern of consumption of alcohol and the lifestyle of the drinker are the real interferences of cardiovascular effects. Although it is believed that there is a cardioprotective effect of wine, studies have indicated the relevance of its nonalcoholic components, such as phenolic antioxidant components and antithrombotic substances.64-68 Although the differences in relation to the influence of the type of wine whether red or white, have not been discussed the cardiovascular effects are similar in exclusive red, white and other wine drinkers.69 57 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts Confounding variables Although the risks and benefits associated with the moderate use of alcohol does exist, it is important to consider that they can be signs of a wider psychosocial behavior, or the findings could be due to interfering factors and are not necessarily associated with the consumption of alcohol per se, suggesting that its effects are not considered isolated, but as a part of a social and cultural context, or the lifestyle of the drinker. These interfering factors are commonly referred to as confounder factors or confounding variables70,71, and vary depending on the alcohol consumption characteristics or the biological variations of the drinker. Thus, regarding consumption the beneficial effects can suffer interference from composition of the beverage (i. e. wine has polyphenolic substances which can hide the effect of ethanol) and of their pattern of use (quantity and frequency). When the user’s characteristics are considered a real interference of alcohol varies depending on the gender, education level, social economical condition, as well as general condition of health, cognitive functioning, intelligence (IQ), psychiatric comorbidities, lifestyle, diet, and other aspects. Among these factors, especially lifestyle, wine consumers have a healthier food diet than the beer or distilled beverage consumers because they purchase olives, vegetables and products with less fat more frequently.71 This explains or strengthens the beneficial health effects of alcohol. Then, it would be possible to admit that the moderate consumption of alcohol associated with a healthy diet had more positive effects than a combination of drinking and an unhealthy diet. Aside from this, the consumption of alcohol alters ingestion and the metabolism of fatty acids essential to a good diet, altering the regulation of homeostasis.72,73 For this reason, it is still not known if it is the use of alcohol or if it is the consumer and their lifestyle which influence the risks of diseases associated with alcohol. 58 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol final considerations Although the heavy use of alcohol has negatively impacted public health, in parallel, there is evidence that indicates that there are benefits associated with moderate use, especially with cardiovascular events. However, caution is important when considering this relationship, since there are many difficulties in estimating the real effects from the moderate consumption of alcohol, with the tendency of the interviewee to underestimate his consumption. Thus, unnecessary and dangerous generalizations should be avoided. It is important to remember that the health effects of alcohol depend principally on the medical history and the individual risks of the drinker. Since doctors and other health professionals are instruments for the awareness and change of individual habits, it is necessary to provide correct and up-to-date information about the real effects of alcohol so that they can act as multipliers of knowledge among their patients. The participation of the media in this process is also fundamental. Accurate information about the effects of moderate consumption is still scarce, overall due to the lack of standardization of its definition. More research is necessary for an understanding of the real relation between the pattern of consumption of alcohol and its associated effects, aiming at spreading fundamental and secure scientific recommendations to those who drink. Information should be applied specifically to the original conditions, or to a determined group, culture or country, for avoiding imprudent generalizations. In addition to this, it is expected that public health authorities, with the intention of reducing the harmful use of alcohol, transmit clearly and objectively the possible benefits induced by the moderate use, and stimulate healthy practices of consumption. In light of this lack of consensus and generalization of information some general recommendations are suggested, including: •• the general health risk of a heavy drinker can be decreased with the reduction of consumption or by abstinence; 59 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts •• in virtue of the lack of knowledge about the risk of the progression to heavy drinking, abstainers should not be indiscriminately counseled to drink; •• most of people who are light or moderate drinkers should not change their drinking habits, except in special circumstances. references 1. United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention – UNODCCP. World drug report 2007. Available at: www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/ WDR-2007.html. 2. World Health Organization – WHO. Global status report on alcohol. Genebra: WHO, 2004. 3. Meloni JN, Laranjeira R. The social and health burden of alcohol abuse. Rev Bras Psiquiat 2004; Suppl 1:S7-10. 4. Rehm J, Chisholm D, Room R, Lopez AD. Alcohol. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2.ed. Nova York: Oxford University Press, 2006. 5. Elisson RC, Martinic M. The harms and benefits of moderate drinking: summary of findings of an international symposium. Available at: www.AnnalsofEpidemiology. org/issues. 6. Klatsky AL. Alcohol, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Res 2007; 55(3):237-47. 7. Rehm J, Gmel G, Sempos CT, Trevisan M. Alcohol-related morbidity and mortality. Alcohol Res Health 2003; 27(1):39-51. 8. Gunzerath L, Faden V, Zakhari S, Warren K. National institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism report on moderate drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 2004; 28(6):829-47. 9. World Health Organization – WHO. Mental disorder in primary care: alcohol use disorders. 1998. Available at: www.who.int/msa/mnh/ems/primacare/edukit/ wepalc.pdf. 10. Drinking & You. Consumer sites about sensible drinking, national government guidelines and your health for the United Kingdom, United States of America, Canada, France, Espana and Deutschland. Available at: www.drinkingandyou.com. 11. Carlini EA, Galduróz JCF, Noto AR, Nappo AS. I levantamento domiciliar sobre o uso de drogas psicotrópicas no Brasil. São Paulo: Cebrid e Senad, 2002. 12. Centro Brasileiro de Informações sobre Drogas Psicotrópicas – Cebrid. II Levantamento Domiciliar sobre o Uso de Drogas Psicotrópicas no Brasil: estudo envolvendo as 108 maiores cidades do país. São Paulo: Cebrid e Senad, 2007. 13. Galduróz JC, Noto AR, Nappo SA, Carlini EA. Trends in drug use among students in Brazil: analysis of four surveys in 1987, 1989, 1993 and 1997. Braz J Med Biol Research 2005; 37(4):523-31. 60 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol 14. Noto AR, Galduróz JCF, Nappo AS, Fonseca AM, Carlini CMA, Moura YG et al. Levantamento nacional sobre o uso de drogas entre crianças e adolescentes em situação de rua nas 27 capitais brasileiras. São Paulo: Cebrid e Senad, 2003. 15. Laranjeira R, Pinsky I, Zaleski M. Caetano R. I Levantamento Nacional sobre os Padrões de Consumo de Álcool na População Brasileira. São Paulo: Uniad e Senad, 2007. 16. Kerr-Corrêa F, Hegedus AM, Trinca LA, Tucci AM, Kerr-Pontes, LRS, Sanches AF et al. Differences in drinking patterns between men and women in Brazil. In.: Obot IS, Room R. GENACIS - alcohol, gender and drinking problems: perspectives from low and middle income countries. Genebra: WHO, 2005. 17. Ogborne AC, Smart RG. Public opinion on the health benefits of moderate drinking: results from a Canadian National Population Health Survey. Addiction 96(4): 641-9, 2001. 18. Green CA, Polen MR, Janoff SL, Castleton DK, Perrin NA. Not getting tanked: definitions of moderate drinking and their health implications. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007; 86(2-3):265-73. 19. Ramos SP, Woitowitz AB. Da cervejinha com os amigos à dependência de álcool: uma síntese do que sabemos sobre esse percurso. Rev Bras Psiquiatria 2004; 26 (1):18-22. 20. Stueve A, O’Donnell LN. Early alcohol initiation and subsequent sexual and alcohol risk behaviors among urban youth. Am J Public Health 2005; 95(5):887-93. 21. McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Morales M, Young A. Simultaneous and concurrent polydrug use of alcohol and prescription drugs: prevalence, correlates, and consequences. J Stud Alcohol 2006; 67(4):529-37. 22. Andersson B, Hibell B, Beck F, Choquet M, Kokkevi A, Fotiou A et al. Alcohol and drug use among European 17-18 year old students - Data from the ESPAD Project: the Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (CAN), council of Europe, co-operation group to combat drug abuse and illicit trafficking in drugs (Pompidou Group). Stockholm: Sweden, 2007. 23. Reed MB, Wang, R, Shillington, AM, Clapp, JD, Lange, JE. The relationship between alcohol use and cigarette smoking in a sample of undergraduate college students. Addict Behav 2007; 32: 449-64. 24. Pennings JM, Leccese AP, Wolff FA. Effects of concurrent use of alcohol and cocaine. Addiction 2002; 97: 773-83. 25. Medina KL, Shear PK, Schafer J. Memory functioning in polysubstance dependent women. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006; 84: 248-55. 26. Midanik LT, Tam TW, Weisner C. Concurrent and simultaneous drug and alcohol use: results of the 2000 national alcohol survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007; 90(1):72-80. 27. Nalpas B, Combescure C, Pierre B, Ledent T, Gillet C, Playoust D et al. Financial costs of alcoholism treatment programs: a longitudinal and comparative evaluation among four specialized centers. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research 2003; 27(1):51-6. 61 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts 28. Leinoe EB, Hoffmann MH, Kjaersgaard E, Nielsen JD, Bergmann OJ, Klausen TW et al. Prediction of haemorrhage in the early stage of acute myeloid leukaemia by flow cytometric analysis of platelet function. Br J Haematol 2005; 128(4):526-32. 29. Boffetta P, Hashibe M, La Vecchia C, Zatonski W, Rehm J. The burden of cancer attributable to alcohol drinking. Int J Cancer 2006; 119(4):884-7. 30. Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med 2004; 38(5):613-9. 31. McPherson. Moderate alcohol consumption and cancer. AEP 2007; 17 (5S)S46-S8. 32. Szabo G. Moderate drinking, inflammation and liver disease. Ann Epidemiol 2007; 17(supl):S49-S54. 33. Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 1997; 25(1):108-11. 34. Jamal MM, Saadi Z, Morgan TR. Alcohol and hepatitis C. Dig Dis 2005; 23(34):285-96. 35. Ethen MK, Ramadhani TA, Scheuerle AE, Canfield MA, Wyszynski DF, Druschel CM et al. Alcohol consumption by women before and during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 2008. 36. Pinheiro SN, Laprega MR, Furtado EF. Morbidade psiquiátrica e uso de álcool em gestantes usuárias do Sistema Único de Saúde. Revista de Saúde Pública 2005; 39 (4):593-8. 37. Lebel C, Rasmussen C, Wyper K, Walker L, Andrew G, Yager J et al. Brain diffusion abnormalities in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Alcohol: Clin Exp Res 2008; 32 (10):1-8. 38. Burden MJ, Jacobson SW, Sokol RJ, Jacobson JL. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on attention and working memory at 7.5 years of age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005; 29(3):443-52. 39. Alati R, Mamun AA, Williams GM, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Bor W. In utero alcohol exposure and prediction of alcohol disorders in early adulthood. A Birth Cohort Study Arch Gen Psych 2006; 63:1009-16. 40. Barr HM, Bookstein FL, O’Malley KD, Connor PD, Huggins JE, Streissguth AP. Binge drinking during pregnancy as a predictor of psychiatric disorders on the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV in young adult offspring. American J Psych 2006; 163:1061-5. 41. Mukherjee RAS, Mohammed SH, Abou-Saleh T. Low level alcohol consumption and the fetus. Abstinence from alcohol is the only safe message in pregnancy. BMJ 2005; 330:375-6. 42. Sood B, Delaney-Black V, Covington C, Nordstrom-Klee B, Ager J, Templin T et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure and childhood behavior at age 6 to 7 years: I. dose-response effect. Pediatrics 2001; 108(2):E34. 43. Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Bagnardi V, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: an updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166(22):2437-45. 62 Principal long term consequences related to moderate consumption of alcohol 44. Koppes JM, Dekker HF, Hendriks LM, Bouter LM, Heine RJ, Meta-analysis of the relationship between alcohol consumption and coronary heart disease and mortality in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2006; 49(4):648-52. 45. Baglietto L, English DR, Hopper JL, Powles J, Giles GG. Average volume of alcohol consumed, type of beverage, drinking pattern and the risk of death from all causes. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2006; 41(6): 664-71. 46. Klatsky AL, Udaltsova N. Alcohol drinking and total mortality risk. Annals of Epidemiology 2007; 17 (5), S63-S7. 47. Klatsky AL, Friedman GD, Siegelaub AB. Alcohol consumption before myocardial infarction. Results from the Kaiser-Permanente epidemiologic study of myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 1974; 81(3): 294-301. 48. Thandani R, Camargo Jr CA, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC, Wilett WC, Rimm EB. Prospective study of moderate alcohol consumption and risk of hypertension in young women. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:569-74. 49. Koppes LL, Dekker JM, Hendriks HF, Bouter LM, Heine RJ. Moderate alcohol consumption lowers the risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta analysis of prospective observational studies. Diabetes Care 2005; 28:719-25. 50. Beulens JW, Bots ML, Grobbee DE. Moderate alcohol consumption may be recommended for the prevention of heart attacks. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2007; 151(49): 2716. 51. Conigrave KM, Hu BF, Camargo CA Jr, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Rimm EB. A prospective study of drinking patterns in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes among men. Diabetes 2001; 50(10):2390-5. 52. Bell RA, Mayer-Davis EJ, Martin MA, D’Agostino RB Jr, Haffner SM. Associations between alcohol consumption and insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Insulin Resistance and Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care 2000; 23:1630-6. 53. Ruitenberg A, van Swieten JC, Witteman JC, Mehta KM, van Duijn CM, Hofman A et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: the Rotterdam study. Lancet 2002; 359(9303):281-6. 54. Deng J, Zhou DH, Li J, Wang YJ, Gao C, Chen M. A 2-year follow-up study of alcohol consumption and risk of dementia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2006; 108(4):37883. 55. Mukamal KJ, Kuller LH, Fitzpatrick AL, Longstreth WT Jr, Mittleman MA, Siscovick DS. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of dementia in older adults. JAMA 2003; 289(11):1405-13. 56. Stampfer MJ, Kang JH, Chen J, Cherry R, Grodstein F. Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cognitive function in women. New England Journal of Medicine 2005; 352(3):245-53. 57. Wright CB, Elkind MSV, Rundek T, Boden-Albala B, Paik MC, Sacco RL. Alcohol intake, carotid plaque, and cognition: the Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke 2006; 37:1160-4. 63 Alcohol and its consequences: dealing with multiple concepts 58. Truelsen T, Thudium D, Gronbaek M. Copenhagen city heart study. Amount and type of alcohol and risk of dementia. Neurology 2002; 59(9):1313-9. 59. Letenneur L. Moderate alcohol consumption and risk of developing dementia in the elderly: the contribution of prospective studies. AEP 2007; 17(5S):S43-S5. 60. Booyse FM, Pan W, Harper VM, Tabengwa EM, Parks DA, Bradleu KM et al. Mechanisms by which alcohol and wine polyphenols affect coronary heart disease risk. Ann Epidemiol 2007; 17(supl):S24-S31. 61. Leger AS, Cochrane AL, Moore F. Factors associated with cardiac mortality in developed countries with particular reference to the consumption of wine. Lancet 1979; 1(8124):1018-20. 62. Gronbaek M, Deis A, Sorensen TI, Becker U, Schnohr P, Jensen G. Mortality associated with moderate intakes of wine, beer, or spirits. BMJ 1995; 310(6988):1165-9. 63. Renaud SC, Guéguen R, Siest G, Salamon R. Wine, beer, and mortality in middleaged men from eastern France. Arch Intern Med 1999; 13:159(16):1865-70. 64. Renaud S, de Lorgeril M. Wine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart disease. Lancet 1992; 339(8808):1523-6. 65. Frankel EN, Kanner J, German JB, Parks E, Kinsella JE. Inhibition of oxidation of human low-density lipoprotein by phenolic substances in red wine. Lancet 1993; 341(8843):454-7. 66. Pace-Asciak CR, Hahn S, Diamandis EP, Soleas G, Goldberg DM. The red wine phenolics trans-resveratrol and quercetin block human platelet aggregation and eicosanoid synthesis: implications for protection against coronary heart disease. Clin Chim Acta 1995; 235(2):207-19. 67. Zakhari S. Molecular mechanisms underlying alcohol-induced cardioprotection: contribution of hemostatic components. Introduction to the symposium. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999; 23(6):1108-10. 68. Booyse FM, Parks DA. Moderate wine and alcohol consumption: beneficial effects on cardiovascular disease. Thromb Haemost 2001; 86(2):517-28. 69. Klatsky AL, Armstrong MA, Friedman GD. Red wine, white wine, liquor, beer, and risk for coronary artery disease hospitalization. Am J Cardiol 1997; 15;80(4):416-20. 70. Fillmore KM, Golding JM, Graves KL, Kniep S, Leino EV, Romelsjö A et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality. Characteristics of Drinking Groups. Addiction 1998; 93(2):183-203. 71. Gronbaek M. Confounders of the relation between type of alcohol and cardiovascular disease. AEP 2007; 17(5S):S13-S5. 72. Simon JA, Fong J, Bernert JT Jr, Browner WS. Relation of smoking and alcohol consumption to serum fatty acids. Am J Epidemiol 1996; 144(4):325-34. 73. Kim SY, Breslow RA, Ahn J, Salem N. Alcohol consumption and fatty acid intakes in the 2001-2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 2007; 31(8)1407-14. 64