The role of free choice in memory for past decisions

advertisement

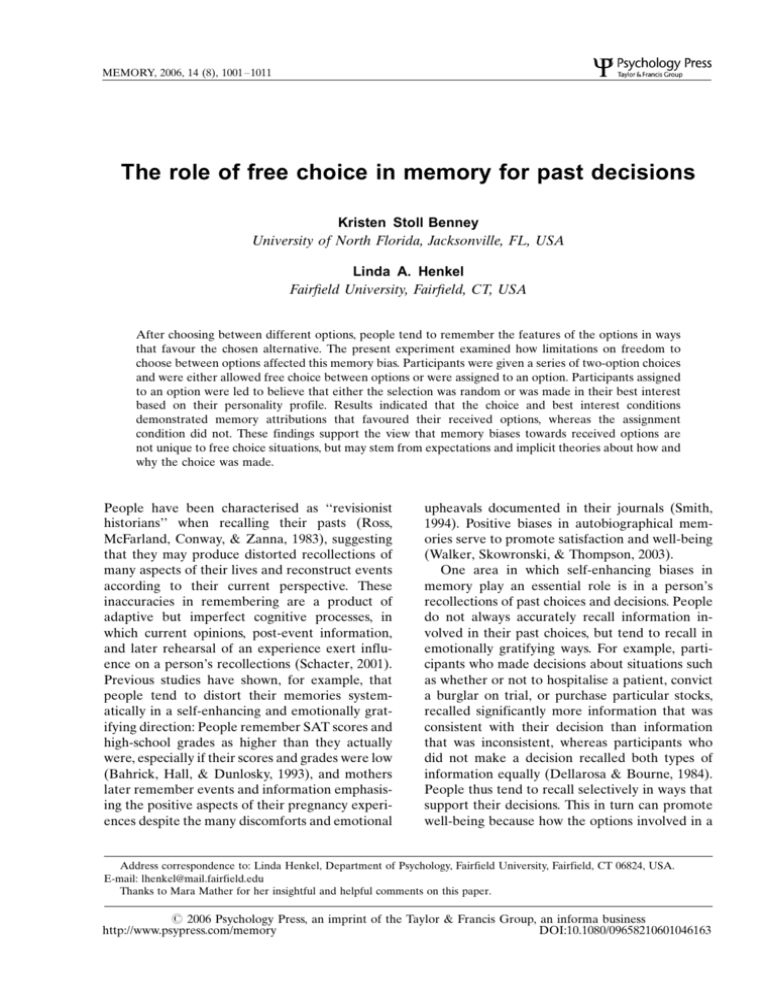

MEMORY, 2006, 14 (8), 1001 1011 The role of free choice in memory for past decisions Kristen Stoll Benney University of North Florida, Jacksonville, FL, USA Linda A. Henkel Fairfield University, Fairfield, CT, USA After choosing between different options, people tend to remember the features of the options in ways that favour the chosen alternative. The present experiment examined how limitations on freedom to choose between options affected this memory bias. Participants were given a series of two-option choices and were either allowed free choice between options or were assigned to an option. Participants assigned to an option were led to believe that either the selection was random or was made in their best interest based on their personality profile. Results indicated that the choice and best interest conditions demonstrated memory attributions that favoured their received options, whereas the assignment condition did not. These findings support the view that memory biases towards received options are not unique to free choice situations, but may stem from expectations and implicit theories about how and why the choice was made. People have been characterised as ‘‘revisionist historians’’ when recalling their pasts (Ross, McFarland, Conway, & Zanna, 1983), suggesting that they may produce distorted recollections of many aspects of their lives and reconstruct events according to their current perspective. These inaccuracies in remembering are a product of adaptive but imperfect cognitive processes, in which current opinions, post-event information, and later rehearsal of an experience exert influence on a person’s recollections (Schacter, 2001). Previous studies have shown, for example, that people tend to distort their memories systematically in a self-enhancing and emotionally gratifying direction: People remember SAT scores and high-school grades as higher than they actually were, especially if their scores and grades were low (Bahrick, Hall, & Dunlosky, 1993), and mothers later remember events and information emphasising the positive aspects of their pregnancy experiences despite the many discomforts and emotional upheavals documented in their journals (Smith, 1994). Positive biases in autobiographical memories serve to promote satisfaction and well-being (Walker, Skowronski, & Thompson, 2003). One area in which self-enhancing biases in memory play an essential role is in a person’s recollections of past choices and decisions. People do not always accurately recall information involved in their past choices, but tend to recall in emotionally gratifying ways. For example, participants who made decisions about situations such as whether or not to hospitalise a patient, convict a burglar on trial, or purchase particular stocks, recalled significantly more information that was consistent with their decision than information that was inconsistent, whereas participants who did not make a decision recalled both types of information equally (Dellarosa & Bourne, 1984). People thus tend to recall selectively in ways that support their decisions. This in turn can promote well-being because how the options involved in a Address correspondence to: Linda Henkel, Department of Psychology, Fairfield University, Fairfield, CT 06824, USA. E-mail: lhenkel@mail.fairfield.edu Thanks to Mara Mather for her insightful and helpful comments on this paper. # 2006 Psychology Press, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business http://www.psypress.com/memory DOI:10.1080/09658210601046163 1002 BENNEY AND HENKEL choice are recollected forms the basis for a person’s feelings of either satisfaction or regret. Recent studies examining ‘‘choice-supportive memory distortion’’ found similar results (Mather & Johnson, 2000; Mather, Shafir, & Johnson, 2000, 2003). After choosing between two different options (e.g., two potential roommates), each associated with positive and negative features (e.g., likes to cook, easily annoyed), people tended to recall more positive features being associated with the selected option and more negative features associated with the rejected option, regardless of which option the features were originally associated with. This systematic bias can serve to promote satisfaction and contentment with one’s choice. This finding that objective features of chosen and rejected options are remembered in a choicesupportive manner is consistent with work on how people change their initial evaluations of options after making a choice (e.g., Brehm, 1956), a result often interpreted in the context of cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957). Clearly, the act of choosing has a powerful impact on people’s cognitions about the past. However, individuals do not always freely choose for themselves. For example, students may be assigned lab partners by a professor and employees may be assigned specific projects by their supervisors. Are choicesupportive memory biases unique to situations in which an individual has free choice? Do people exhibit these biases when an option is assigned, rather than chosen? Recent research suggests that freedom to make choices for yourself leads to different memory attributions than from having choices made for you (Mather et al., 2003). Participants who freely chose between pairs of options based on their described features remembered in a choice-supportive manner, whereas those who imagined being assigned to options did not. People expected the assigned option to be remembered better, and therefore acted on the expectation that the features they recalled most vividly were associated with the assigned option. Thus, it is not only commitment to an option that drives biases in memory, but the act of choosing for oneself that may lead to different cognitive operations from when one does not have free choice, as shown in other work across a variety of research paradigms (e.g., Desrichard & Monteil, 1994; Harmon-Jones & Mills, 1999; Wenzlaff & LePage, 2000). For example, studies have found better memory for self-chosen than for assigned or rejected actions, and a bias in people with an impaired ability to cope with negative affect to erroneously claim that they chose to perform an activity that in fact was not freely selected but was assigned to be performed (Baumann & Kuhl, 2003; Kuhl & Kazen, 1994). Presumably this bias serves to increase positive affect and satisfaction. Although Mather et al. (2003) provide evidence that arbitrary assignment to an option does not prompt memory attributions in favour of the received option, those who were assigned an option were not provided with any information about how or why the choice was made. Such information may be a critical factor in prompting choice-supportive memory attributions, and that is the focus of the present study. A large body of research suggests that memory may be guided by expectations (Hirt, 1990; Klein & Kunda, 1993; McDonald & Hirt, 1997; Snyder & Uranowitz, 1978) and implicit beliefs about oneself and others (see Ross, 1989, for a review). In the case of memory for past choices, it is possible that expectations and beliefs about how the choice was made may guide memory processes. For example, people who chose an option may hold a belief that they received the superior option, and therefore recall features of that option based on that belief. A person who has been assigned an option might display similar memory biases if prompted to hold positive expectations and beliefs about the received option (e.g., participants who believed an assignment was made with their best interest in mind might reconstruct their memory to favour the option received). Recent work has highlighted the important role that beliefs play in making memory attributions about features associated with chosen and rejected options (Henkel & Mather, in press). Participants chose between two options in a series of choice scenarios and were later asked to remember which options they had chosen and to indicate which options various features had been associated with. In one study, participants sometimes misremembered which of the two options they had actually chosen, and in another study, they were given misleading reminders suggesting that they had earlier chosen the option that they had in fact rejected. Results showed that people made attributions favouring the option they believed that they chose, even when that belief was erroneous. In order to further determine the role that beliefs might play in choice-supportive biases, the present research placed different limitations on participants’ freedom to choose during a FREE CHOICE AND MEMORY FOR DECISIONS series of decisions. Some participants freely chose for themselves in a series of two-option decision scenarios (choice condition), whereas others were told the computer would randomly choose options for them (assignment condition). A third ‘‘best interest’’ group was told the computer would choose for them based on an individualised profile of information about their personal preferences (in fact, the computer chose randomly). Participants either received the chosen or assigned items from the decision scenarios or were entered in a raffle to win them. This provided a realistic choice with a direct outcome, rather than a hypothetical or imagined choice as used in prior research (Mather et al., 2003). We expected to replicate findings from previous studies in the free choice and assignment conditions, with participants demonstrating choice-supportive memory attributions in the former group and a lack of choice-supportiveness in the latter (Mather et al., 2003). The best interest condition was included to provide information about the factors necessary to prompt choice-supportiveness. Although participants in this condition did not freely choose for themselves, they were prompted to believe that the choice was made in their best interest, representing a high-quality choice for them. Thus, if choicesupportiveness stems from expectations and beliefs about the quality of options received, these participants should demonstrate biases favouring the assigned option. However, if there is something inherent in the act of choosing for oneself that prompts a bias towards the chosen option, they should not demonstrate choice-supportive memory attributions. METHOD Participants Participants were 192 undergraduates (45 males, 147 females) ranging in age from 18 to 52 years old (M /21.74) at a mid-sized, south-eastern university. They participated to fulfil course requirements or receive extra credit. Materials and procedure Under the guise of collecting ‘‘personal attribute and preference’’ information, participants com- 1003 pleted a series of 12 two-option questions on a computer (e.g., Would you rather watch television or read a book?; Do you prefer to be spontaneous or to plan events carefully?). Next, participants were told they would be presented a series of choices between two options and should read the descriptions of the options carefully to decide which one they preferred. They viewed four different two-option scenarios involving restaurants, movie theatres, department stores, and chewing gum (see Appendix). They were told they would either receive the chosen/ assigned item (e.g., gum) or be entered into a raffle to win a gift certificate for it later (e.g., restaurant gift certificate). In each scenario, the two options appeared side by side on the computer screen. Beneath each option was a list of six to nine descriptive features. Each option in a pair had the same number of positive and negative features. Two additional scenarios (involving puzzles and magazines) were presented last and served as the basis for a later filler task. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: free choice, best interest, or assignment. Participants in the free choice condition were instructed to press the key that corresponded with their preferred option. The best interest group was instructed to press the space bar because the computer would choose between the two options based on their answers to the personal attribute and preference questions, and would display the option selected for them. They were informed that the computer had an 85% success rate for choosing participants’ preferred option. The assignment group was instructed to press the space bar because the computer would randomly choose between the two options and display the selected option. They were told that random assignment was necessary to make the chances of winning each raffled item equal across participants. For both the best interest and assignment groups, selection of all options was random. In all conditions, it was emphasised that participants should review the features associated with each option and decide which of the two options they preferred before indicating their choice or hitting the key to view the choice made for them. The six scenarios were completed one at a time in a self-paced manner. After each choice, participants rated their satisfaction with the choice and their confidence that the decision was the right one for them on a scale from 1 (not confident/satisfied) to 7 (very confident/satisfied ). 1004 BENNEY AND HENKEL This served to motivate participants in all conditions to attend to and evaluate the options. Participants then completed several personality questionnaires and engaged in filler tasks (doing the puzzle and reading the magazine previously chosen or assigned), establishing a 30-minute delay prior to a surprise memory test. We administered separate source memory tests for each of the four scenarios. Each test consisted of the names of the two options, followed by a randomised list of the various descriptive features participants viewed when deciding which option they preferred. Intermixed with the original (old) features were three positive and three negative new features not originally associated with either option. Participants indicated which option they had chosen or were assigned, then indicated whether each feature was associated with Option A or Option B, or was new. RESULTS Of the 192 participants, 20 could not correctly remember two or more of the four chosen/ assigned options and thus were excluded from analyses (11 from the best interest condition, 1 from the choice condition, and 8 from the assignment condition). This resulted in 172 participants (60 in the best interest condition, 55 in the free choice condition, and 57 in the random assignment condition). All analyses and post-hoc comparisons (Newman-Keuls) were conducted using an alpha level of .05. Recognition accuracy Differences were examined across the three conditions in people’s overall ability to remember features that occurred, regardless of which option they were attributed to. An ANOVA on recognition accuracy (i.e., the proportion of original features recognised as old and new features recognised as new) showed a significant main effect of condition, F (2, 169) / 3.14, MSe/ 0.01, 1 An analogous ANOVA on corrected recognition scores (to factor out guessing biases) revealed similar results. A greater number of participants in the best interest and random assignment conditions were eliminated from all analyses because they failed to correctly remember more than two of the assigned options. Nonetheless, when their data were included in the recognition analyses, the patterns and significance remain the same. p / 0.046.1 Recognition accuracy in the free choice condition (M / 0.87) was significantly higher than in the best interest condition (M / 0.84), but did not differ from the assignment condition (M / 0.85). Proportion of items attributed to chosen and nonchosen options One way in which to examine choice-supportive memory biases is to determine whether there are differences in the proportion of positive or negative features attributed to either the chosen or nonchosen option in each of the choice/assignment conditions. A choice-supportive bias would be indicated by attributions favouring the chosen option over the nonchosen option (i.e., more positive features attributed to the chosen than the nonchosen option; more negative features attributed to the nonchosen than the chosen option). Separate analyses were conducted for old and new items. The proportion of recognised old items attributed to either the chosen or nonchosen option was examined for each of the three choice/assignment conditions.2 As can be seen in the top panel of Table 1, in both the best interest and free choice conditions, a choicesupportive bias was shown for positive features: Participants attributed significantly more positive old features to the chosen option than to the nonchosen option, t (59) / 2.45, p / .02; t (54) / 3.20, p / .002, respectively. However, in the assignment condition, they did not show such a bias, t (56) / 0.70, p / .49. The bottom panel of Table 1 shows the proportion of new items incorrectly attributed to one of the two options, and a bias favouring the nonchosen option can be seen. Participants in the random assignment condition attributed more negative features to the chosen option than the nonchosen option, although the effect was only marginally significant, t (56) /1.70, p/ .09. These findings are consistent with the argument that people make memory attributions in a manner that favours the chosen over the nonchosen option, and that the nature of the choice*whether it was freely made, made in one’s best interest, or made randomly* influences the pattern of attributions. 2 Analyses were also conducted in which the proportion of old items attributed to either the chosen or nonchosen options was calculated out of the total number of old items presented, and these analyses yielded identical patterns. FREE CHOICE AND MEMORY FOR DECISIONS 1005 TABLE 1 Proportion of positive and negative features attributed to either the chosen or nonchosen option as a function of freedom to choose Positive old features Negative old features Attributed to chosen Attributed to nonchosen Attributed to chosen Attributed to nonchosen .55 (.12) .53 (.10) .49 (.10) .45 (.12) .47 (.10) .51 (.10) .49 (.08) .51 (.10) .51 (.06) .51 (.08) .49 (.10) .49 (.06) Choice Best interest Assignment Positive new features Negative new features Attributed to chosen Attributed to nonchosen Attributed to chosen Attributed to nonchosen .11 (.12) .15 (.13) .11 (.12) .12 (.12) .16 (.12) .13 (.12) .06 (.06) .08 (.08) .09 (.10) .07 (.11) .09 (.09) .05 (.09) Choice Best interest Assignment SD in parentheses. Asymmetry scores Another way to examine choice-supportive attributions is through a composite measure that indicates the extent to which participants remember relatively more positive features belonging to the selected option and more negative features belonging to the nonselected option. Asymmetry scores to measure this bias were calculated using the method described by Mather et al. (2000) and Mather and Johnson (2000), following this basic formula: (Proportion of positive features attributed to Option A / Proportion of negative features attributed to Option B) (Proportion of negative features attributed to Option A / Proportion of positive features attributed to Option B). The resulting sums were standardised separately for the four scenarios such that the mean value across all participants for each scenario was zero. A positive value indicated memory attributions favouring Option A over Option B, and a negative value indicated memory attributions favouring Option B over Option A (standardised scores were multiplied by /1 for participants who chose or were assigned Option B). The resulting asymmetry score provides a measure of whether and how much participants favoured the options received (either by choice or by assignment). Positive scores indicate memory attributions favouring the option people received (e.g., attributing more positive features and fewer negative features to the received option). Negative scores indicate that participants favoured the option they did not receive (e.g., attributing more negative features and fewer positive features to the chosen option). A score of 0 indicates that choices or assignments did not influence memory attributions. This particular measure is valuable not only because it provides a composite score of the degree of choice-supportiveness but also because it avoids spurious effects due to unequal numbers of participants choosing one option over another. For example, if the great majority of participants chose the Corner Café over the American Grille restaurant and also showed attributions favouring the Corner Café, but the two tendencies were not correlated, a significant choice-supportive asymmetry score would not be obtained. Unequal numbers of participants choosing one option over another would in fact underestimate the extent of bias when one option is overwhelmingly preferred, and thus would reduce the likelihood of revealing a choice-supportive bias (e.g., in the most extreme case, if everyone in a given sample chose the same option, the mean asymmetry score would be zero; see Mather et al., 2003, footnote 3 for further discussion). Because we cannot control which option participants select in the choice condition, imbalances in choices naturally arise (unequal numbers of participants chose one option over the other in each scenario: 21/34 in the department store choice, 36/19 in the gum choice, 36/19 in the movie choice, and 20/35 in the restaurant choice). Furthermore, although in the best interest and assignment conditions equal numbers of participants were assigned to the two options, the elimination of participants who failed to correctly remember more than half of the chosen options resulted in unequal numbers assigned to a given option. A repeated-measures ANOVA showed no significant differences in overall asymmetry 1006 BENNEY AND HENKEL scores between the four scenarios, F(3, 603) / 0.43, p / .73. Therefore, we averaged the asymmetry scores for the scenarios for each participant, using only scores from correctly remembered choices/assignments, and weighted the averages based on number of features per scenario. An ANOVA on overall asymmetry scores indicated a significant main effect for choice/ assignment condition, F (2, 169) / 5.06, MSe / 1.34, p / .007 (see Figure 1). Asymmetry scores for the assignment group significantly differed from both the free choice group and the best interest group, and the best interest and free choice groups did not differ. Overall asymmetry scores significantly differed from zero for both the free choice condition, F(1, 54) / 4.74, MSe / 1.51, p / .03, and the best interest condition, F (1, 59) / 4.44, MSe / 1.27, p / .04, indicating that both groups displayed memory attributions favouring the option received. In contrast, the mean asymmetry score for the assignment condition was negative and marginally differed from zero, F (1, 56)/ 3.61, MSe / 0.68, p / .06, indicating that memory attributions tended to favour the alternative (non-received) option. Thus, the best interest and choice groups both favoured the received option, whereas the assignment group did not. To further examine biases in memory attributions, a 2 /3/3 ANOVA was conducted on asymmetry scores, with feature valence (positive, negative) and attribution type (correct attribu- tions of old features, misattributions of old features, misattributions of new features) as within-subjects factors, and condition (free choice, best interest, random assignment) as a between-subjects factor (see Table 2). Overall, participants were significantly more choice-supportive for positive features than for negative features, F(1, 169) / 6.06, MSe / 0.30, p / .01. A significant main effect was also found for the condition under which choices were made, F (2, 169) / 4.75, MSe / 0.52, p/ .02, replicating the result found with overall asymmetry scores. The assignment group significantly differed from both the free choice and best interest groups, but the free choice and best interest groups did not differ. Again, these results indicate that those who freely chose or had choices made presumably in their best interest were choice-supportive, whereas those for whom a choice was made randomly were not. No difference was found in asymmetry scores for the different types of attributions, F (2, 338) / 1.13, MSe / 0.18, p / .32, although a significant valence / attribution type interaction was found, F (2, 338) / 3.67, MSe / 0.22, p / .03. For negative features, asymmetry scores were relatively low and did not differ in relation to the type of attribution made; however, for positive features, both correctly and incorrectly attributed old features resulted in higher asymmetry scores than did incorrectly attributed new features. Thus people were more likely to attribute (both correctly and incorrectly) positive old features to the selected option relative to the 0.25 0.20 Overall Asymmetry Score 0.15 0.10 0.05 Assignment 0.00 Choice Best Interest -0.05 -0.10 -0.15 -0.20 -0.25 Figure 1. Overall asymmetry scores (9/SE) as a function of freedom to choose. (Positive scores indicate memory attributions favouring the selected option; negative scores indicate memory attributions favouring the nonselected option; scores of 0 indicate attributions favouring neither the selected nor nonselected option). FREE CHOICE AND MEMORY FOR DECISIONS 1007 TABLE 2 Mean weighted asymmetry scores as a function of choice condition, feature valence, and type of attribution Positive features Correct Choice Best interest Assignment Total .29 .19 /.05 .14 (.71) (.50) (.50) (.59) Incorrect .17 .21 /.05 .11 (.64) (.45) (.47) (.53) Negative features New .01 .04 /.04 .01 (.41) (.59) (.48) (.50) Correct .00 /.03 /.00 /.01 (.52) (.56) (.41) (.50) Incorrect .01 .05 /.10 /.01 (.53) (.57) (.41) (.51) New .07 .12 /.09 .03 (.42) (.57) (.46) (.49) SD in parentheses. Correct/old features attributed to the correct option; Incorrect /old features attributed to the incorrect option; New /new features incorrectly attributed to either option. unselected option, but did not do so for new features. Satisfaction and confidence ratings Participants’ ratings of satisfaction with the option received and confidence in the choice/assignment were averaged across the four choice scenarios. Due to a programming problem, ratings from three participants were not saved. An ANOVA on average satisfaction rating for the remaining participants indicated a significant main effect for choice/assignment condition, F (2, 166) / 5.91, MSe / 0.93, p / .003. Post-hoc tests indicated that participants in the free choice group were significantly more satisfied (M / 4.91) than those in either the best interest group (M / 4.31) or the assignment group (M / 4.43). The best interest and assignment groups did not significantly differ. A significant main effect was also found for average confidence ratings, F (2, 166) / 10.71, MSe / 0.90, p B/ .001. Those in the choice condition gave significantly higher confidence ratings that the selected option was the right one for them (M / 5.06) than did those in the best interest (M / 4.37) or assignment (M / 4.30) conditions, and the latter two did not differ significantly. DISCUSSION Free choice is not always an option, and choices made on one’s behalf can either seem arbitrary or seem to be in one’s best interest. Results from the present study suggest that people’s memory attributions about chosen/assigned options depend in part on beliefs about the quality of the received option, and these beliefs can promote either satisfaction and well-being or dissatisfaction and regret. Specifically, findings showed that the act of freely choosing one option over another prompted memory attributions favouring the chosen option, whereas being arbitrarily assigned to an option did not prompt memory attributions favouring that option. In fact, assignment to an option actually prompted participants to slightly favour the forgone option (demonstrated by negative asymmetry scores and a slightly higher proportion of negative new features attributed to the chosen than the nonchosen option). Unlike prior research, the present study explored a situation in which individuals were assigned to an option in their own best interest, paralleling many naturalistic instances, such as a spouse making a decision about a restaurant for a partner, or a supervisor deciding which project the employee is to work on. Participants in the best interest condition demonstrated a pattern of memory attributions favouring the received option, similar to the choice group, which indicates that free choice is not the sole necessary condition to induce choice-supportiveness. Having a choice made in one’s best interest is sufficient to prompt memory attributions favouring the received option. The findings highlight the fact that people rely on different heuristics in making attributions about their memories (e.g., Bayen, Nakamura, Dupuis, &Yang, 2000; Mather et al., 2003; Sherman & Bessenhoff, 1999), a key point intrinsic to the source-monitoring framework (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993). Participants in both the choice and best interest groups appear to rely on a belief or judgement heuristic that their chosen or assigned option is the superior one. Conversely, those in the assignment group do not appear to operate using this belief. Their tendency to favour the nonchosen option may 1008 BENNEY AND HENKEL reflect regret or dissatisfaction with the outcome, prompted by the assignment (as seen in their reduced satisfaction and confidence ratings), and hence these participants may rely on a belief * implicit or explicit *that they received a less than desirable option or may be forced to base their source attributions on other heuristics such as how vividly each feature is recalled (Mather et al., 2003). This is consistent with recent work showing that beliefs about which option was chosen are a driving force behind the attributions people make, even when those beliefs are erroneous (Henkel & Mather, in press). Although care was taken to motivate participants to pay attention to the choices and evaluate their associated features in all the conditions, by having them rate their satisfaction with the choice and their confidence that the decision was the right one for them, it is possible that participants in the choice condition simply paid more attention to the features than did those who did not freely choose, and this differential encoding influenced subsequent memory. Indeed, recognition accuracy was higher in the choice condition than in the best interest condition. However, the choice and assignment groups did not differ in recognition performance but significantly differed in asymmetry scores, suggesting that group differences in recognition of old and new features was not the sole basis for differences in memory bias toward the received option. These results show there is not a simple linear relationship between recognising an option as old or new and making source attributions that favour the received option, a finding consistent with principles of the source-monitoring framework purporting that source identification and old new recognition can draw on different aspects of memories (e.g., familiarity vs specific qualitative features) and involve different evaluative processes (see Johnson et al., 1993). Past research in which people’s beliefs about which of the two options they chose was directly manipulated offers further evidence that selective encoding alone cannot account for choice-supportive biases (Henkel & Mather, in press). Satisfaction and confidence ratings provide additional information relevant to understanding the influence of beliefs about choices on subsequent memory attributions. Directly after choosing or being assigned an option, satisfaction and confidence ratings were significantly higher in the choice condition than the other two conditions. The best interest and assignment groups were not as satisfied as those in the free choice group, presumably because they were not afforded free choice and may have preferred the alternative option. However, at the time of the memory test (30 minutes later), the best interest group displayed memory attributions favouring the received option, similar to the choice group. This finding supports the idea that reconstructive processes at the time of retrieval and source evaluation contribute to the phenomenon of choice-supportive memory (Mather & Johnson, 2000). At encoding, the best interest group was similar to the assignment group in satisfaction with the received option, yet at retrieval their attributions favoured the received option at levels similar to the choice group. The fact that the best interest condition and the free choice condition were dissociated on every measure (recognition, satisfaction, and confidence ratings) except the choice-supportive memory bias is particularly revealing. On each of these other measures, the best interest condition closely resembled the random assignment condition, suggesting that the depth of encoding and initial attitudes about the options were quite similar in these two assignment conditions. Despite these initial similarities, participants were subsequently biased in favour of their assigned option when they were led to believe the assignment was made with their best interest in mind, rather than being arbitrary. This is important evidence that beliefs about the quality of the chosen option relative to forgone options are what lead to the choice-supportive source attribution bias. These findings also speak to the well-known phenomenon of cognitive dissonance reduction. A rich assortment of studies has shown that people may alter their behaviours, attitudes, and beliefs to reduce the discomfort of harbouring inconsistent ideas or to justify their actions and choices (e.g., Harmon-Jones & Mills, 1999). Such studies generally examine preferences and changes in one’s attitudes. Memory measures such as those employed here are an alternative way to measure how conflicting cognitions (e.g., the option I chose is the best option but has some undesirable features) are shifted to become more consonant. Both research from the tradition of cognitive dissonance and the present work converge on the view that our cognitive processes serve to promote feelings of satisfaction and wellbeing, whether in the context of attitude changes of which we are unaware or systematic biases in FREE CHOICE AND MEMORY FOR DECISIONS recollections of past decisions. The present findings suggest that these biases are not limited to those who choose for themselves. Rather, people assigned an option in their best interest display memory attributions that emphasise the positive and downplay the negative, thereby making their memory of the decision consistent with the idea that the choice was truly made in their best interest. Participants in the best interest group would be more likely than those in the random assignment group to have conflicting cognitions that would lead to dissonance-reduction processes when a less appealing choice is selected for them because, unlike in the assignment group where the selection was random, the selection in the best interest group was ostensibly based on a profile of their preferences and personality. Cognitive dissonance effects are generally stronger in situations that involve the self-concept (e.g., Aronson & Carlsmith, 1962; Stone & Cooper, 2001). Several other aspects of the present findings are worthy of further consideration. As in prior research showing choice-supportive memory attributions, people in the present study showed stronger biases favouring the chosen option in their attributions of positive rather than negative features (Henkel & Mather, in press; Mather & Johnson, 2000; Mather et al., 2000). This is especially compelling, because in past research on choice-supportive memory attributions people tend to better remember negative rather than positive information, and are more likely to correctly remember the source of negative information (e.g., Mather et al., 2003). In general, people weigh negative information more heavily than positive information when making decisions and forming impressions (Kanouse & Hanson, 1972; Tversky & Kahneman, 1991). It may be that in some situations, such as relatively low-consequence choices as in the present paradigm, positive information is less well remembered and thus more susceptible to reconstructive memory processes that promote satisfaction and well-being. Additional research is needed to more systematically address this possibility (e.g., by manipulating the amount, salience, or importance of various positive and negative features in conjunction with restrictions of one’s freedom to make choices for oneself). Another point to consider from the present findings is that choice-supportive memory attributions were more prominent for old features than for new features. Prior research has shown that attributions favouring the chosen option can 1009 occur for both studied items and for new items (Henkel & Mather, in press; Mather & Johnson, 2000; Mather et al., 2000). This is likely due to the fact that fewer new items and a shorter delay between encoding and retrieval were used here than in prior research. Again, beliefs are more likely to guide memory reconstruction when people’s memory for the original information is not as strong (see Henkel & Mather, in press). In conclusion, this study has shown that free choice is not the sole condition required for memory attributions that favour a received option; rather, beliefs about the quality of an option and expectations about the means used to make a decision may influence a person’s memory attributions. Making a choice or having a choice made for you in your best interest prompt memory attributions that support that choice. This may represent a positive illusion that promotes wellbeing (Mather et al., 2000; Taylor & Brown, 1998). Conversely, being randomly assigned to an option leads to a different set of cognitions and memory attributions that tend to favour the alternative (non-received) option and may emphasise regret and disappointment. Manuscript received 22 December 2005 Manuscript accepted 21 August 2006 REFERENCES Aronson, E., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1962). Performance expectancy as a determinant of actual performance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 65 , 178 182. Bahrick, H. P., Hall, L. K., & Dunlosky, J. (1993). Reconstructive processing of memory content for high versus low test scores and grades. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 7 , 1 10. Baumann, N., & Kuhl, J. (2003). Self-infiltration: Confusing assigned tasks as self-selected in memory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 29 , 487 497. Bayen, U. J., Nakamura, G. V., Dupuis, S. E., & Yang, C. L. (2000). The use of schematic knowledge about sources in source monitoring. Memory & Cognition , 28 , 480 500. Brehm, J. W. (1956). Post-decision changes in the desirability of choice alternatives. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52 , 384 389. Dellarosa, D., & Bourne, L. E. (1984). Decisions and memory: Differential retrievability of consistent and contradictory evidence. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 23 , 669 682. Desrichard, O., & Monteil, J. (1994). When cognitive dissonance is also memory-based. Psychological Reports, 75 , 1331 1336. 1010 BENNEY AND HENKEL Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson. Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (1999). Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Henkel, L.A., & Mather, M. (in press). Memory attributions for choices: How beliefs shape our memories. Journal of Memory and Language. Hirt, E. R. (1990). Do I see only what I expect? Evidence for an expectancy-guided retrieval model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58 , 937 951. Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin , 114 , 3 28. Kanouse, D. E., & Hanson, L. R. J. (1972). Negativity in evaluations. In E. E. Jones, D. E. Kanouse, H. H. Kelley, R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 47 62). Morristown, NY: General Learning Press. Klein, W., & Kunda, Z. (1993). Maintaining self-serving social comparisons: Biased reconstruction of one’s past behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 19 , 732 739. Kuhl, J., & Kazen, M. (1994). Self-discrimination and memory: State orientation and false self-ascription of assigned activities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66 , 1103 1115. Mather, M., & Johnson, M. K. (2000). Choice-supportive source monitoring: Do our decisions seem better to us as we age? Psychology and Aging, 15 , 596 606. Mather, M., Shafir, E., & Johnson, M. K. (2000). Misremembrance of options past: Source monitoring and choice. Psychological Science, 11 , 132 138. Mather, M., Shafir, E., & Johnson, M. K. (2003). Remembering chosen and assigned options. Memory & Cognition , 31 , 422 433. McDonald, H., & Hirt, E. (1997). When expectancy meets desire: Motivational effects in reconstructive memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72 , 5 23. Ross, M. (1989). Relation of implicit theories to the construction of personal histories. Psychological Review, 96 , 341 357. Ross, M., McFarland, C., Conway, M., & Zanna, M. P. (1983). Reciprocal relation between attitudes and behavior recall: Committing people to newly formed attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45 , 257 267. Schacter, D. L. (2001). The seven sins of memory. New York: Houghton-Mifflin. Sherman, J., & Bessenhoff, G. (1999). Stereotypes as source-monitoring cues. Psychological Science, 10 , 106 110. Snyder, M., & Uranowitz, S. (1978). Reconstructing the past: Some cognitive consequences of person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36 , 941 950. Smith, J. A. (1994). Reconstructing selves: An analysis of discrepancies between women’s contemporaneous and retrospective accounts of the transition to motherhood. British Journal of Psychology, 85 , 371 392. Stone, J., & Cooper, J. (2001). A self-standards model of cognitive dissonance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37 , 228 243. Taylor, S., & Brown, J. (1998). Illusion and well-being. Psychological Bulletin , 103 , 193 210. Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference dependent model. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107 , 1039 1061. Walker, W. R., Skowronski, J. J., & Thompson, C. P. (2003). Life is pleasant and memory helps to keep it that way! Review of General Psychology, 7 , 203 210. Wenzlaff, R., & LePage, J. (2000). The emotional impact of chosen and imposed thoughts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 26 , 1502 1514. APPENDIX Options and Associated Features Restaurant Choice: Corner Café . . . . . . . . . Salad cost is included with most meals (/) Has both lunch and dinner options (/) Some dishes are bland ( /) Great desserts (/) Kitchen is noisy ( ) Comfortable seating (/) Poorly lit (/) Not much variety (/) Generous portions (/) American Grille . . . . . . . . . Friendly waiters and waitresses (/) Delicious appetisers (/) Long wait for tables (/) Well decorated, pleasant atmosphere (/) Slow service (/) Affordably priced (/) Uses a lot of canned, processed food (/) Plays annoying background music (/) Close to shopping and entertainment areas (/) Movie Theatre Choice: Theatretown . . . . . . . Easy to drive to (/) Snacks are very expensive ( ) Superb sound quality (/) Short concession lines (/) Uncomfortable seats (/) Always has the most newly released movies showing (/) Ushers are often rude to customers ( /) FREE CHOICE AND MEMORY FOR DECISIONS Cinemaplex . . . . . . . Plenty of parking (/) Candy is often stale ( /) Stadium seating (/) Popcorn is always hot and fresh (/) Dirty restrooms (/) Shows are rarely sold out (/) Projector occasionally breaks down (/) Department Store Choice: Pewter & Lowe . . . . . . . . Sales staff is very helpful (/) Layout of store is confusing ( ) Carries popular men’s and women’s fragrances (/) Large, private dressing rooms (/) Very strict return/refund policy (/) Nice selection of home decorating items (/) Some people consider their styles old-fashioned (/) Never crowded (/) Clark’s . . Many sizes of clothing in stock (/) Doesn’t carry many name brands (/) . . . . . . Large shoe department (/) Often has big sales (/) Rarely has advertised merchandise in stock (/) Wide variety of casual and formal clothing (/) Difficult to drive to (/) Close to many restaurants (/) Gum Choice: Dentachew . . . . . . Long lasting flavor (/) Is a little gritty at first (/) Pieces are very small (/) Minty tasting (/) Low in calories (/) Tends to get difficult to chew within a short amount of time (/) Chewy-licious . . . . . . Breath freshening (/) Sometimes leaves a bad aftertaste (/) Goes stale quickly (/) Easy to chew (/) Helps prevent cavities (/) Contains chemical additives (/) 1011