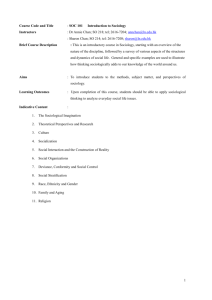

SOCIOLOGY 1A: The Sociological Imagination

advertisement