The Clean Up Crew - Missouri Prairie Foundation

advertisement

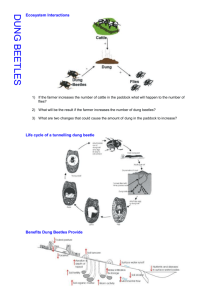

JAMES TRAGER Invertebrates: the little things that run the world –E.O. Wilson P R A I R I E I N V E R T E B R AT E S THE CLEAN UP C A VARIETY OF INSECT DECOMPOSERS ARE THE CU When the life of one organism ends, the work of insect decomposers begins. These insects consume excrement or dead plants or animals, and in the process help to recycle nutrients, returning materials to the soil or atmosphere. Some insect decomposers are general omnivores that feed on a variety of decaying organic matter—cockroaches, for example— while others are more selective about the type of dead material they consume. 14 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 Nos. 3 & 4 Recyclers of Plants The sheer quantity of the total mass of plant material found in prairies is well beyond that of other prairie life, even beyond the total mass of bison, the heavyweights of the prairie. While much of this plant growth is consumed by herbivores, the remaining grasses, wildflowers, and occasional shrub and tree eventually die and become detritus. At this point, recyclers step in to eat the dead plant material, a process that helps to return nutrients and minerals to the soil and carbon dioxide and other gasses to the atmosphere. Although bacteria are critical to the decomposition process, without the preparation insects provide by chewing, fragmenting, and passing detritus through their digestive systems, bacteria cannot work quickly or efficiently. Flies, beetles, cockroaches, caterpillars, and termites all consume dead plant material, but termites in particular play a large role in recycling plants. Termites are social insects. Their colonies in the prairie region have thousands of individuals. Together the colony members—workers, reproductives, soldiers—consume massive amounts of plant matter on the surface and in the soil. Cellulose, a structural compound that is JAMES TRAGER MICHAEL JACOBS ST. LOUIS ZOO At far left is a decomposer and pollinator in one: According to Dr. James Trager, entomologist and MPF technical advisor, the adult of this honeybee mimic, Eristalis tenax, a fly native to Eurasia but now naturalized in North America, is a pollinator. Its larvae, however, are decomposers. The larvae—known as rat-tailed maggots—feed on decaying matter in shallow, eutrophic water or very moist soil, or sometimes even carrion. REW Pictured in the center are termite adult workers. While termites are well known for decomposing rotting logs in forests or wooden elements of buildings, there are two species on prairies that are important recyclers of plants. At far right are larvae of the American burying beetle. The adult beetles bury carrion of small animals and lay eggs in the burial chamber; when the larvae hatch, the adults feed them regurgitated carrion—a parenting behavior uncommon in the insect world. By Jennifer Hopwood S T O D I A N S O F T H E P R A I R I E. abundant in plants, is indigestible for many animals. The guts of termites, however, contain symbiotic bacteria and protozoa that break down the compound and allow termites to digest cellulose. Termites and other plant decomposers eat hundreds of pounds of dead plants each year. While termites may be most often associated with rotting logs in forests or wooden elements of buildings, there are two species that live on prairies. Recyclers of Carrion The bodies of animals provide nourishment to a variety of insects, including blow flies, flesh flies, house flies, burying beetles, hide beetles, some hister and darkling beetles, and clothes moths. Insects that dispose of dead animals play an invaluable ecological role. Collagen, a protein abundant in mammals, and keratin, found in hair and tissue of many animals, are indigestible compounds to most organisms, yet some insect decomposers can break down these compounds and utilize the released amino acids. As unappetizing as it may seem, the carcass of a dead animal is a hot commodity on the prairie. Carrion is not a predict- able or abundant resource, so competition for it may be fierce. Not only must carrion-feeding insects compete with each other for the food, they also need to compete with larger scavengers such as coyotes, crows, and vultures. As such, carrion-feeding insects are often strong fliers and are remarkably sensitive to odors. Some species also employ other tactics to take advantage of the ephemeral food source. Some flesh flies deposit larvae, rather than eggs, in carrion, skipping a step in development that might allow them a competitive edge over other flies that must undergo the egg stage first. To get a jump on the competition, one group of blow flies lays its eggs in wounds of injured animals, not even waiting for death. Burying beetles prevent access by their competitors to the carrion by taking the body and burying it. When they find a carcass, burying beetles tunnel underneath it until the carcass sinks deeply enough to be covered by soil. Then the beetles, which may work as individual pairs or cooperatively in small groups, lay eggs in the burial chamber. When the eggs hatch, adults feed their young larvae regurgitated carrion until the larvae can feed off the body Vol. 35 Nos. 3 & 4 Missouri Prairie Journal 15 Pictured here are two of the thousands of insect decomposers that recycle dung: from left are blow flies (on coyote scat) and a dung beetle. By consuming dung, these decomposers carry out many important ecological functions, including releasing nitrogen back into the soil where it can be absorbed by plants. Ants as Decomposers Ants are not decomposers in the same sense as detritivores. Their contribution to decomposition is, however, significant given that literally millions of ants can occur on a prairie. Many ants will opportunistically grab up dead insects and other invertebrates and carry them home to eat. They also may feed on carrion too large to carry, scraping off edible bits and lapping up the more liquid component to take to their colonies. They may also do this with dung, especially that of insectivores and carnivores. A number of them, such as the species in the picture below, also gather dry plant fragments and build up the structure of their mounds with them. The combination of the ants’ nitrogenous waste and accumulated plant matter decomposes in the latrine portions of their nests to locally enrich soil. — Dr. James Trager, entomologist and MPF technical advisor JAMES TRAGER Jennifer Hopwood is a Senior Pollinator Conservation Specialist with the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. She is based in Nebraska and is an MPF member. Formica pallidefulva individuals cooperating to carry home a charred earthworm on a warm day after a prairie burn. 16 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 Nos. 3 & 4 JAMES TRAGER Recyclers of Dung Animals excrete at least 40 percent of what they eat, and dung feeders, which are mainly beetles and flies, consume that excrement. As with carrion, there is a great deal of competition for excrement because it is an unpredictable resource. While some adult beetles or flies may lay eggs directly in animal excrement so their offspring can feed on it, others (mainly scarab beetles) move it to a more secure and convenient location before laying their eggs. Dung beetles will eat excrement from a variety of animals, but many prefer dung from herbivores, such as cattle and bison. Some beetles will dig burrows under the dung, and pull dung down into the tunnels. Tumblebug dung beetles pat dung into a ball and roll it away from the main dung mass to their burrows where they later lay their eggs. As dung beetle larvae munch away, they break down the dung and release nitrogen back into the soil where it can be absorbed by plants. Ball-rolling beetles have been fascinating people for ages; dung beetles were sacred and symbolic to ancient Egyptians, for example. In prairies that are grazed by large mammal herbivores, insect recyclers of dung also increase grazing indirectly by making grass and other prairie plants more palatable for cattle, elk, and bison. They also decrease the exposure of livestock to biting pest insects, which breed in moist places such as dung that has not yet been broken down. The ecological and economical value of dung beetles became obvious soon after the introduction of cattle in the late 1880s to Australia, a continent with no native placental mammals. Although the native Australian dung beetles could process the dung of marsupials such as kangaroos, they were unable to fully break down cattle dung, which proceeded to accumulate rapidly. In 1968, the government introduced species of dung beetles accustomed to processing cattle dung, thereby saving the burgeoning Australian cattle and dairy industry. Death comes to all living things. The work of insect decomposers helps bring forth life out of death. JAMES TRAGER themselves, and mother beetles remain with their progeny until they are ready to pupate. Small carrion, such as dead insects and earthworms, is effectively cleaned up and recycled by ants, crickets, rove beetles, millipedes, and harvestmen, also known as “daddy long-legs.”