NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development

advertisement

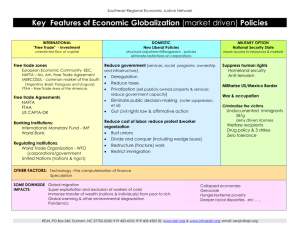

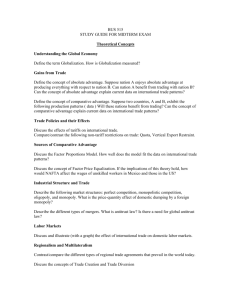

Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Columbia University June 6, 2014 NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Mexico’s Disappointing Growth Performance I Despite concerted efforts at market-oriented reforms since the mid-1980s, Mexico’s growth has underperformed that of other middle-income countries. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Hanson: Why Isn’t Mexico Rich? 989 vs. Latin-American Countries Panel A. Latin America Log per capita GDP (1980 = 0) 1 Mexico Brazil Venezuela Argentina Chile 0.5 0 −0.5 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Year Source: Hanson (2010).Asia Panel B. Southeast = 0) 1.5 Mexico Malaysia Thailand NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Indonesia Philippines Eric Verhoogen −0.5 Introduction Existing Approaches 1980 1985 Sectoral Shifts and Innovation 1990 Conclusion 1995 2000 2005 1995 2000 2005 Year vs. Asian Countries Panel B. Southeast Asia Log per capita GDP (1980 = 0) 1.5 Mexico Malaysia Thailand Indonesia Philippines 1 0.5 0 −0.5 1980 1985 1990 Year Source: Hanson (2010). Figure 1: Economic Growth in Comparison Countries (continued) NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLVIII (December 2010) 990 vs. Eastern Europe Panel C. Eastern and Central Europe Log per capita GDP (1980 = 0) 0.8 Mexico Hungary Turkey 0.6 Bulgaria Romania 0.4 0.2 0 −0.2 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Year Source: Hanson (2010). Figure 1: Economic Growth in Comparison Countries (continued) are insufficient to explain the Mexican case. Because some countries in Latin America have done well in the last decade, Mexico’s perforNAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development relative to Asia and Europe, which during the second half of the twentieth century did converge toward U.S. income levels, was due pri-Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Mexico’s Disappointing Growth Performance (cont.) I Big question: What role has NAFTA (or integration more broadly) played in this growth experience? NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Mexico’s Disappointing Growth Performance (cont.) I Big question: What role has NAFTA (or integration more broadly) played in this growth experience? I There are a number of plausible alternative factors that have contributed to the disappointing performance (Hanson, 2010; Kehoe and Ruhl, 2010): I I I I I Monopolies and inefficient regulation (Arias et al., 2010). Underdeveloped credit markets (Haber, 2004). Informality and evasion (Levy, 2008). Corruption and, more recently, violence. ... All of these likely played a role. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Mexico’s Disappointing Growth Performance (cont.) I Big question: What role has NAFTA (or integration more broadly) played in this growth experience? I There are a number of plausible alternative factors that have contributed to the disappointing performance (Hanson, 2010; Kehoe and Ruhl, 2010): I I I I I Monopolies and inefficient regulation (Arias et al., 2010). Underdeveloped credit markets (Haber, 2004). Informality and evasion (Levy, 2008). Corruption and, more recently, violence. ... All of these likely played a role. I But let’s focus for now on trade/integration. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Plan of Talk I Introduction I Some Observations about Existing Approaches I Sectoral Shifts and Innovation I Conclusion NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion The Empirical Challenge I As many others have noted, evaluating NAFTA is difficult because other things changed at the same time: I Trade liberalization of mid-1980s. I Events in 1990s may have been delayed reaction. I Peso crisis. I As Krueger (2000) and others have noted, devaluation was much larger (50% nominal devaluation) than tariff changes (10% reductions in Mexico, 3-5% in US). NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion The Empirical Challenge I As many others have noted, evaluating NAFTA is difficult because other things changed at the same time: I Trade liberalization of mid-1980s. I Events in 1990s may have been delayed reaction. I Peso crisis. I As Krueger (2000) and others have noted, devaluation was much larger (50% nominal devaluation) than tariff changes (10% reductions in Mexico, 3-5% in US). I Two broad categories of approaches to evaluating the effects of NAFTA: I Applied general equilibrium modeling. I Reduced-form, typically difference-in-differences. I will argue that there is something missing from each. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Applied General Equilibrium Modeling I Ably reviewed by Kehoe (2005), and yesterday’s keynote. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Applied General Equilibrium Modeling I Ably reviewed by Kehoe (2005), and yesterday’s keynote. I Advantage: Can make theoretically well-grounded statements about general-equilibrium effects, welfare. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Applied General Equilibrium Modeling I Ably reviewed by Kehoe (2005), and yesterday’s keynote. I Advantage: Can make theoretically well-grounded statements about general-equilibrium effects, welfare. I Issue: Valid only if the model is right. (A big “if.”) NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Applied General Equilibrium Modeling I Ably reviewed by Kehoe (2005), and yesterday’s keynote. I Advantage: Can make theoretically well-grounded statements about general-equilibrium effects, welfare. I Issue: Valid only if the model is right. (A big “if.”) I My reading of Tim’s reading: I Applied GE models did not perform particularly well in predicting the effects of NAFTA. I One issue is new goods margin. I Aggregate changes seem to be driven largely by TFP changes. But models for the most part do not endogenize TFP. “It may be that we applied GE modelers eventually decide that the biggest effect of liberalization of trade and capital flows is on productivity — through changing the distribution of firms and encouraging technology adoption — rather than the effects emphasized by the models used to analyze the impact of NAFTA.” (Kehoe, 2005, p. 372) NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Reduced-Form Approaches I A number of authors have followed what De la Cruz et al. (2013) call “econometric” approaches, e.g. difference-in-differences. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Reduced-Form Approaches I A number of authors have followed what De la Cruz et al. (2013) call “econometric” approaches, e.g. difference-in-differences. I Advantage: Require weaker assumptions ex ante. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Reduced-Form Approaches I A number of authors have followed what De la Cruz et al. (2013) call “econometric” approaches, e.g. difference-in-differences. I Advantage: Require weaker assumptions ex ante. I Issue: generally have to give up on making statements about general equilibrium effects, welfare. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Reduced-Form Approaches I A number of authors have followed what De la Cruz et al. (2013) call “econometric” approaches, e.g. difference-in-differences. I Advantage: Require weaker assumptions ex ante. I Issue: generally have to give up on making statements about general equilibrium effects, welfare. I De la Cruz et al. (2013) provide a nice review. Here I’ll make a few observations, with a focus on effects on productivity in Mexico. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Lopez Cordova (2003) I Emphasizes 3 channels: I Import-discipline effect. I Improved access to intermediate inputs, machinery. I Reallocation toward more productive plants. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Lopez Cordova (2003) I Emphasizes 3 channels: I Import-discipline effect. I Improved access to intermediate inputs, machinery. I Reallocation toward more productive plants. I Using data from Encuesta Industrial Anual for 1993-2000, first estimates TFP using Olley and Pakes (1996) method. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Lopez Cordova (2003) I Emphasizes 3 channels: I Import-discipline effect. I Improved access to intermediate inputs, machinery. I Reallocation toward more productive plants. I Using data from Encuesta Industrial Anual for 1993-2000, first estimates TFP using Olley and Pakes (1996) method. I Then regresses TFP on tariffs, controlling for plant, industry, geographical characteristics. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen 1 1 Of c o <0 "> 3 s 10 t & o o T? oOOoo t? o8^r un o o oo oo o o * lo '? on lo o o (NO OO O O O O % >^- r- rvo r? > O Tf r? t? ,-; O O O O r^d % _^ i^. *? ?_, on rs MIS ?s oS VO Un ?tf- t? ^r? OMTl VOr? CDCD ^t- r? r? r? O CD ??'CD OO CDO O O t on rNoo r? cr\ vooo vpoo 0000rs CT* ts 00 "*JrN <?3" crv vpCD ^-r? ?^?? ts ?? oovo ^r on "T rs ^-oo Ort? CD r? ^"t? O ?-; OJ (N CTJON CDCDOO O'O O O O O O* O $ rN oo CDoo OOO rnr oin rNO 00CDCD O* O O* O ?:= CDCD r- CD o o O? <* oo vp o o ?=S LO or- Tf O-3 O CD O O B-?i uj: CD* CD CD CDO 00 tj- rsi r^ O O O CD :=3 ?2? O ?;: 00 I?. VO ', _ . - . -2 SS OO I ?u_ S E -S w c I ?ui_ ?.5 ? c S U^ VO 00 00 00 CD CDCD O O 5 i_l. i 1 s o>ro on SIS OOr- o> ** o> *? r- vo on on 00o on rv on rN Or "^t? OO unO r-CD OOO OOCT? OrO??; rN??; un on 00*-; oo??; "?^00 CDCD i-^O O O CDCD CDCD CDCD .5 P*. CD VO0> un 00 on CD CD CD uoo^T cdO o CDO CDO t un o\ un von vo t? 00 00 00 rN rs rr? VO CD ?^ r? rN^" CD OAr- ON CDCD CDCD CDCD VJ un CDO CD CDCD CD O i ? &J II fO s Eric Verhoogen NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Conclusion Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Existing Approaches Introduction Lopez Cordova (2003) (cont.) Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Lopez Cordova (2003) (cont.) I Findings: I Mexican tariffs ↓ ⇒ TFP ↑ I U.S. tariffs ↓ ⇒ TFP ↑ I Use of imported inputs does not seem to have robust positive effect on TFP. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Lopez Cordova (2003) (cont.) I Findings: I Mexican tariffs ↓ ⇒ TFP ↑ I U.S. tariffs ↓ ⇒ TFP ↑ I Use of imported inputs does not seem to have robust positive effect on TFP. I There are things to criticize here: I TFP lumps mark-ups, measurment error, possibly output and input quality with technical efficiency. I Did not include plant effects. Are results driven by cross-sectional variation? but overall the results are credible that NAFTA had positive within-sector effects on productivity. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction that enhance access to source of a Conclusion country’s co (Bernard & Bradford Je Data source: EIA not find evidence that ex growth. However, a poss Figure 4. Labor productivity performance by integration status. dent improvements in th as opposed to importers cess for Mexican export given that US tariffs w changes for importers ha more, with the boom in after NAFTA, many of t selves in the new situat exporters with far higher catching up with these n explanation behind the importers. Unfortunately port this hypothesis ex descriptive analysis (Sect Finally, consistent with 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 Hoekman, 2000; Evenett year appears to be an importa Exporter and Importer Just Exporting plants acquired, or with p Just Importing ever, data limitations do Source: INEGI, BANXICO and Authors’ Calculations nel in more detail becaus the foreign ownership of Figure 5. Impact of NAFTA on productivity by integration status for all son, we decided not to pu firms. of FDI and the potential this study, even if we are The results of this paper confirm the importance of the imof productivity changes port-competition As previously in various per plots coefficientschannel. from regression ofsuggested log value-added worker on analysis. empirical studies (Fernandes, 2007; Pavcnik, 2002; Tybout & Existing Approaches Non−integrated Exporters Fully Integrated Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Importers −.1 0 Treatment Effect .1 .2 .3 De Hoyos and Iacovone (2013) I Figure time * dummies for importer/exporter/both. I Results robust to throwing out switchers. NOTES NAFTA and Mexican Industrial 1. Development In the paper we refer interchangeably to firm or plant to identify the Verhoogen 4. See for Eric example Markuse Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Iacovone (2012) L. Iacovone / Journal of Development Economics 99 (2012) 474–485 ⁎⁎ 481 Marginal Effect of % Tariff Change on % Productivity Growth 1.5 OLS FE (3) (4) 0.260⁎⁎⁎ (0.015) − 0.012⁎⁎⁎ (0.002) 0.173⁎⁎⁎ (0.008) 0.002⁎⁎⁎ 0.391⁎⁎⁎ (0.014) − 0.015⁎⁎⁎ (0.002) 0.499⁎⁎⁎ (0.011) 0.006⁎⁎⁎ (0.001) 0.045⁎⁎⁎ (0.003) 0.021⁎⁎⁎ (0.002) 0.083⁎⁎⁎ (0.009) 0.004⁎⁎⁎ (0.001) 0.086⁎⁎⁎ (0.013) 0.004 (0.003) − 0.026 (0.016) 0.006⁎⁎⁎ (0.001) 0.006⁎⁎⁎ (0.002) 0.004⁎⁎⁎ (0.001) Yes Yes Yes No Yes 44,176 0.075 1 0.5 0 -0.5 -1 OLS FE -1.5 1% 5% 10% 25% 50% Mean 75% 90% 95% 99% Percentile - Distance from Frontier Fig. 3. Marginal effect of tariffs on productivity growth. Second, wefrom run a simple regression evaluate the correlation beI(0.002) Effects calculated regression of to4log value-added/worker on tween the NAFTA total tariff cuts between 1994 and 2002 and average No interaction of distance to frontier and level of tariff (and industry or plant measures of capital or skill intensity at the 6-digit industry level in No Yes effects). 1994. The results suggest that while there is a positive correlation beYes tween tariff cuts and skill intensity this is not statistically significant IYes Distance(see is ratio of value-added/worker to avg value-added/worker of 5 Table 9 in the online appendix). 44,176 leading firms in we each Third, arguesector. that if the HO reallocation was at play we should 0.217 observe sales increasing in sectors characterized by tariff reductions. However, in columns (1) and (2) of Table 1, we exactly showed that NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Verhoogen (2008) Figure IV Exports, High-quality Models as Percentage of VW Output 100 90 Percentage of total output 80 70 60 50 40 % output exported 30 % output New Beetle/Jetta/Golf 20 10 0 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 Notes: Output measured in physical units. Omitted model from upper curve is the Original Beetle. Data from Bulletins of the Asociacion Mexicana de la Industria Automotriz (Mexican Automobile Industry Association). Notes: Uses data from the Bulletins of the Asociación Mexicana de la Industria Automotriz (AMIA). Production measured in number of vehicles. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Verhoogen (2008) (cont.) n-Parametric Regressions, Changes 1993-1997 and 1997-2001 App. Fig. Vb: Changes in log white-collar wage Δ log real white-collar wage 0.2 994-1997 998-2001 0.1 0 -0.1 change 1993-1997 change 1997-2001 -0.2 -0.3 1 2 -3 -2 -1 0 log domestic sales, initial year 1 2 App. Fig. Vd: Changes in log wage ratio Notes: Uses data from balanced panel of non-maquiladora plants from the Encuesta Industrial Anual (EIA). 0.05 NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Existing Approaches: Summary I Both approaches have made progress, but both also seem to me to be missing something important. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Existing Approaches: Summary I Both approaches have made progress, but both also seem to me to be missing something important. I Applied GE: NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Existing Approaches: Summary I Both approaches have made progress, but both also seem to me to be missing something important. I Applied GE: I Sectoral shifts central to analysis. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Existing Approaches: Summary I Both approaches have made progress, but both also seem to me to be missing something important. I Applied GE: I Sectoral shifts central to analysis. I But relatively little attention to productivity changes that are endogenous to trade liberalization. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Existing Approaches: Summary I Both approaches have made progress, but both also seem to me to be missing something important. I Applied GE: I Sectoral shifts central to analysis. I But relatively little attention to productivity changes that are endogenous to trade liberalization. I Reduced-form: NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Existing Approaches: Summary I Both approaches have made progress, but both also seem to me to be missing something important. I Applied GE: I Sectoral shifts central to analysis. I But relatively little attention to productivity changes that are endogenous to trade liberalization. I Reduced-form: I Documents productivity changes. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Existing Approaches: Summary I Both approaches have made progress, but both also seem to me to be missing something important. I Applied GE: I Sectoral shifts central to analysis. I But relatively little attention to productivity changes that are endogenous to trade liberalization. I Reduced-form: I Documents productivity changes. I But relatively little attention to effects of sectoral shifts on ongoing productivity growth. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Sectoral Shifts and Innovation I Old-fashioned idea (Prebisch, 1950; Matsuyama, 1992): I Different activities are associated with different inherent rates of innovation, productivity growth. I Liberalization changes to pattern of specialization, may lead to specialization in non-dynamic activities. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Sectoral Shifts and Innovation I Old-fashioned idea (Prebisch, 1950; Matsuyama, 1992): I Different activities are associated with different inherent rates of innovation, productivity growth. I Liberalization changes to pattern of specialization, may lead to specialization in non-dynamic activities. I What follows is very low-tech, more “analytical narrative” than definitive analysis. I The hope is that it stimulates more in-depth research into the Mexican and similar cases. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Sectoral Shifts and Innovation I Old-fashioned idea (Prebisch, 1950; Matsuyama, 1992): I Different activities are associated with different inherent rates of innovation, productivity growth. I Liberalization changes to pattern of specialization, may lead to specialization in non-dynamic activities. I What follows is very low-tech, more “analytical narrative” than definitive analysis. I The hope is that it stimulates more in-depth research into the Mexican and similar cases. I No attempt to separate effects of NAFTA, peso devaluation, lingering effects of 1980s liberalization. All probably point in same direction. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Sectoral Shifts and Innovation I Old-fashioned idea (Prebisch, 1950; Matsuyama, 1992): I Different activities are associated with different inherent rates of innovation, productivity growth. I Liberalization changes to pattern of specialization, may lead to specialization in non-dynamic activities. I What follows is very low-tech, more “analytical narrative” than definitive analysis. I The hope is that it stimulates more in-depth research into the Mexican and similar cases. I No attempt to separate effects of NAFTA, peso devaluation, lingering effects of 1980s liberalization. All probably point in same direction. I More details on my website (text of a talk I gave in Monterrey, published in Boletin Informativo Techint.) NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion 2 Employment Growth vs. Skill Intensity, 1988-1998 Apparel & textile prod. Transportation equip. −.5 0 .5 1 Other 4−digit NAICS industries −1.5 −1 change in log(employment), 1988−1998 1.5 Electrical/electronic prod. 0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5 .6 Share >=12 yrs education (in large plants), 1998 Notes: Data on employment growth are from the INEGI Economic Censuses from 1989 and 1999 (containing information from previous year). Data on schooling are from 1999 ENESTyC. Each symbol represents a 4-digit industry in the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS). The size of the symbols reflect employment in the industry in 1998. The fitted regression line is weighted by employment in 1998. See Figure A1 of Verhoogen (2008). NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion 2 Employment Growth vs. Capital Intensity, 1988-1998 Apparel & textile prod. Transportation equip. −.5 0 .5 1 Other 4−digit NAICS industries −1.5 −1 change in log(employment), 1988−1998 1.5 Electrical/electronic prod. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 log capital−labor ratio, 1998 Notes: Data on employment growth and capital-labor ratio are from the INEGI Economic Censuses from 1989 and 1999 (containing information from previous year). Each symbol represents a 4-digit industry in the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS). The size of the symbols reflect employment in the industry in 1998. The fitted regression line is weighted by employment in 1998. A similar graph (using a different industry classification) appeared as Figure A2 of Verhoogen (2008). NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion 2 Employment Growth vs. Skill Intensity, 1998-2008 Apparel & textile prod. Transportation equip. −.5 0 .5 1 Other 4−digit NAICS industries −1.5 −1 change in log(employment), 1998−2008 1.5 Electrical/electronic prod. 0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5 .6 Share >=12 yrs education (in large plants), 1998 Notes: Data on employment growth are from the INEGI Economic Censuses from 1989 and 1999 (containing information from previous year). Data on schooling are from 1999 ENESTyC. Each symbol represents a 4-digit industry in the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS). The size of the symbols reflect employment in the industry in 1998. The fitted regression line is weighted by employment in 1998. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion 2 Employment Growth vs. Capital Intensity, 1998-2008 Apparel & textile prod. Transportation equip. −.5 0 .5 1 Other 4−digit NAICS industries −1.5 −1 change in log(employment), 1998−2008 1.5 Electrical/electronic prod. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 log capital−labor ratio, 1998 Notes: Data on employment growth are from the INEGI Economic Censuses from 1989 and 1999 (containing information from previous year). Data on schooling are from 1999 ENESTyC. Each symbol represents a 4-digit industry in the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS). The size of the symbols reflect employment in the industry in 1998. The fitted regression line is weighted by employment in 1998. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Maquiladora and Total Industry Employment Employment (thousands) 200 400 Employment (thousands) 200 400 600 Electrical and Electronic Equipment 600 Apparel all NAICS 315 1995 2000 2005 2010 All NAICS 334 and 335 maquiladoras 0 0 maquiladoras 1990 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Employment (thousands) 200 400 600 Transportation Equipment All NAICS 336 0 maquiladoras 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Notes: Maquiladora employment from EMIME for 1988-2006; total industry employment from Economic Censuses of 1989, 1994, 1999, 2004, and 2009. Apparel and textile products (maquila group 2) mapped to NAICS 315 (apparel manufacturing); transportation equipment (maquila group 6) to NAICS 336 (transportation equipment manufacturing); electrical and electronic equipment (maquila groups 8 and 9) to NAICS 334 and 335 (computer and electronic equipment; and electrical equipment, appliances, and components). NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Means by Sub-Sector: Apparel, Elect. & Trans. Equip. non-maquiladoras Employment non-exporters (1) exporters (2) maquiladoras (3) 315.43 (8.23) 0.08 (0.01) 254.26 (19.11) 0.28 (0.01) 70.18 (0.56) 7.86 (0.04) 3.59 (0.06) 7.45 (0.14) 41.47 (1.22) 6.25 (0.09) 438.97 (11.07) 30.81 (0.72) 0.29 (0.01) 309.07 (14.45) 0.32 (0.01) 70.75 (0.46) 8.15 (0.04) 3.92 (0.05) 9.32 (0.15) 40.54 (1.06) 6.59 (0.08) 969.67 (30.02) 96.52 (0.63) 0.84 (0.02) 54.87 (7.18) 0.19 (0.01) 83.04 (0.63) 7.37 (0.06) 3.83 (0.10) 9.33 (0.27) 72.37 (2.66) 3.53 (0.08) 1423 1774 557 Export percentage of sales Foreign ownership indicator Capital-labor ratio Share with >= 12 years schooling Percentage blue-collar Years of schooling, blue-collar Blue-collar hourly wage White-collar hourly wage Turnover rate Tenure (years) N Notes: Standard errors of means in parentheses. Sample is plants with ≥ 100 employees in 1999 ENESTyC. Capital-labor ratio measured in thousands of 1998 pesos; blue-collar and white-collar hourly wage in 1998 pesos. Average 1998 nominal exchange rate: 9.1 pesos/dollar. Apparel Transport Equip. Electronics NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion The Story So Far I From 1988-1998, manufacturing sector specialized in less capital- and skill-intensive activities, both across sectors and within sectors (i.e. to maquilas). NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion The Story So Far I From 1988-1998, manufacturing sector specialized in less capital- and skill-intensive activities, both across sectors and within sectors (i.e. to maquilas). I From 1998-2008, these sectors/subsectors tended to stagnate. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Role of China I A common explanation: Mexico had bad luck. I Just as Mexico was poised to grow, China entered. I China had similar pattern of specialization in exports to U.S. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Role of China I A common explanation: Mexico had bad luck. I Just as Mexico was poised to grow, China entered. I China had similar pattern of specialization in exports to U.S. I There is definitely evidence to support the China story: I Utar and Torres Ruiz (2013) yesterday. I Kumler (2014): applies approach of Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013) in Mexico. I Lopez Cordova, Micco and Molina (2008), Hanson and Robertson (2010), Hsieh and Ossa (2011). China-Mexico export similarity NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development US import shares Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Role of China I A common explanation: Mexico had bad luck. I Just as Mexico was poised to grow, China entered. I China had similar pattern of specialization in exports to U.S. I There is definitely evidence to support the China story: I Utar and Torres Ruiz (2013) yesterday. I Kumler (2014): applies approach of Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013) in Mexico. I Lopez Cordova, Micco and Molina (2008), Hanson and Robertson (2010), Hsieh and Ossa (2011). China-Mexico export similarity US import shares I But here I would like to argue that China is not the whole story, that Mexico would have had problems even if China had not entered. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion R&D Measure, ENESTyC 1999 I Survey asked: “Since 1997, has the establishment undertaken R&D?” I (If yes) “What did the R&D principally consist of?” “Design of new products” “Process improvements” “Product quality improvements” “Design/Improvement/Manufacture of machinery or equipment” I “Other” I I I I I N.B.: This is a broad, inclusive definition of R&D, not just patents. I Not perfect, but not bad as a first pass. I Code as 0/1. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion .5 Share of plants performing R&D, 1998 1 R&D Intensity vs Skill Intensity, 1998 Apparel & textile prod. Transportation equip. Electrical/electronic prod. 0 Other 4−digit NAICS industries 0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5 .6 Share >= 12 years schooling, 1998 Notes: Size of plotting symbols reflects employment in industry. The fitted regression line is weighted by employment. The estimated slope is 0.53 with standard error 0.13; the R2 is 0.16. Industry-level averages are for large plants (≥ 100 employees). NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion .5 Share of plants performing R&D, 1998 1 R&D Intensity vs Capital Intensity, 1998 Apparel & textile prod. Transportation equip. Electrical/electronic prod. 0 Other 4−digit NAICS industries 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 log capital−labor ratio, 1998 Notes: Size of plotting symbols reflects employment in industry. The fitted regression line is weighted by employment. The estimated slope is 0.05 with standard error 0.01; the R2 is 0.14. Industry-level averages are for large plants (≥ 100 employees). NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion R&D Intensity by Sector non-maquiladoras All manufacturing Apparel Electrical and Electronic Products Transportation Equipment non-exporters (1) exporters (2) maquiladoras (3) 0.36 (0.01) 0.19 (0.03) 0.35 (0.07) 0.40 (0.07) 0.50 (0.01) 0.33 (0.04) 0.54 (0.04) 0.62 (0.04) 0.41 (0.02) 0.34 (0.05) 0.45 (0.03) 0.54 (0.10) Source: ENESTyC 1999. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Alternative Innovation Measure I: Patents per Capita INNOVATION IN MEXICO: NAFTA IS NOT ENOUGH 251 Figure 6.2 Patents per Million Workers, 1960–2000 4.5 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0 19 80 s 19 90 –9 4 19 95 –2 00 0 19 70 s 19 60 s 94 19 95 –2 00 0 19 80 s 19 90 – 19 70 s 19 60 s 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 East Asia Latin America and the Caribbean Mexico Republic of Korea 120 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 100 80 60 40 20 United States Canada 19 90 –9 4 19 95 –2 00 0 19 80 s 19 70 s 19 60 s 19 90 –9 4 19 95 –2 00 0 19 80 s 19 70 s 19 60 s 0 High-income countries Source: U.S. Office of Patents and Trademarks. Notes: From Lederman, Maloney and Servén (2005), based on data from the U.S. Office of Patents and Trademarks. global and long time coverage, and especially because it is commonly understood that the United States offers perhaps the most advanced lev- NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Alternative Innovation Measure II: R&D Spending/GDP Country R&D spending/GDP (%) Mexico Chile China Korea U.S. Canada .38 .65 .65 2.34 2.59 1.76 Notes: Data from World Bank World Development Indicators for 1998. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Summary I Integration led Mexico to specialize in less capital- and skill-intensive activities, both across and within sectors. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Summary I Integration led Mexico to specialize in less capital- and skill-intensive activities, both across and within sectors. I These sectors that Mexico tended to be less innovative. I This did not have to be true. But the correlation appears quite robust. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Summary I Integration led Mexico to specialize in less capital- and skill-intensive activities, both across and within sectors. I These sectors that Mexico tended to be less innovative. I This did not have to be true. But the correlation appears quite robust. I The sectoral shifts thus tended to dampen the overall rate of innovation in the economy. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Summary I Integration led Mexico to specialize in less capital- and skill-intensive activities, both across and within sectors. I These sectors that Mexico tended to be less innovative. I This did not have to be true. But the correlation appears quite robust. I The sectoral shifts thus tended to dampen the overall rate of innovation in the economy. I What if China had not entered? I We don’t observe the counterfactual, but my sense is that there would always be another country moving up the product ladder — Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, ... NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Further Thoughts I More research is needed, needless to say. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Further Thoughts I More research is needed, needless to say. I But patterns suggest that there may be a trade-off between static allocative efficiency and long-term productivity growth. I Liberalization alone may not to be enough to bring about sustained growth. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Further Thoughts I More research is needed, needless to say. I But patterns suggest that there may be a trade-off between static allocative efficiency and long-term productivity growth. I Liberalization alone may not to be enough to bring about sustained growth. I My own view is that policy-makers should consider interventions to promote the sorts of activities that generate innovation and productivity growth. I This argument relies on the idea that innovation generates positive externalities, which I am exploring empirically in other work with co-authors (Atkin et al., 2014) NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Further Thoughts (cont.) I I do not want to argue that such interventions need to happen at the border, in the form of tariffs or other trade barriers. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Further Thoughts (cont.) I I do not want to argue that such interventions need to happen at the border, in the form of tariffs or other trade barriers. I And it is true that governments have no special knowledge about which sectors/firms/ideas/technologies are going to be successful in the future. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Further Thoughts (cont.) I I do not want to argue that such interventions need to happen at the border, in the form of tariffs or other trade barriers. I And it is true that governments have no special knowledge about which sectors/firms/ideas/technologies are going to be successful in the future. I But I think there is a strong case for policies that provide broad-based (sometimes called “horizontal” (Lederman and Maloney, 2012)) support for innovative activities. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion References I Arias, Javier, Oliver Azuara, Pedro Bernal, James J. Heckman, and Cajeme Villarreal, “Policies To Promote Growth and Economic Efficiency in Mexico,” 2010. NBER working paper no. 16554. Atkin, David, Azam Chaudhry, Shamyla Chaudry, Amit K. Khandelwal, and Eric Verhoogen, “Organizational Barriers to Technology Adoption: Evidence from Soccer-Ball Producers in Pakistan,” 2014. Mimeo, Columbia University. Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson, “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States,” American Economic Review, 2013, 103 (6), 2121–68. De Hoyos, Rafael E. and Leonardo Iacovone, “Economic Performance under NAFTA: A Firm-Level Analysis of the Trade-productivity Linkages,” World Development, 2013, 44 (0), 180 – 193. De la Cruz, Justino, David Riker, and Bennet Voorhees, “Econometric Estimates of the Effects of NAFTA: A Review of the Literature,” 2013. U.S. International Trade Commission Office of Economics Working Paper 2013-12A, Dec. Devlin, Robert, Antoni Estevadeordal, and Andres Rodriguez-Clare, The Emergence of China: Challenges and Opportunities for Latin America and the Carribean, Harvard University Press, 2006. Haber, Stephen, “Why Institutions Matter: Banking and Economic Growth in Mexico,” 2004. Stanford Center for International Development working paper no. 234. Hanson, Gordon H., “Why Isn’t Mexico Rich?.,” Journal of Economic Literature, 2010, 48 (4), 987 – 1004. and Raymond Robertson, “China and the Manufacturing Exports of Other Developing Countries,” in “China’s Growing Role in World Trade,” NBER Conference Report series. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 137 – 159. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion References II Hsieh, Chang-Tai and Ralph Ossa, “A Global View of Productivity Growth in China,” 2011. NBER working paper no. 16778. Iacovone, Leonardo, “The better you are the stronger it makes you: Evidence on the asymmetric impact of liberalization,” Journal of Development Economics, 2012, 99 (2), 474 – 485. Kehoe, Timothy J., “An Evaluation of the Performance of Applied General Equilibrium Models of the Impact of NAFTA,” in Timothy J. Kehoe, T. N. Srinivasan, and John Whalley, eds., Frontiers in Applied General Equilibrium Modeling: In Honor of Herbert Scarf, Cambridge University Press, 2005. and Kim J. Ruhl, “Why Have Economic Reforms in Mexico Not Generated Growth?.,” Journal of Economic Literature, 2010, 48 (4), 1005 – 1027. Krueger, Anne, “NAFTA’s Effects: A Preliminary Assessment,” World Economy, June 2000, 23 (6), 761–75. Kumler, Todd, “Chinese Competition and Mexican Labor Markets,” 2014. Unpub. paper, Columbia University. Lederman, Daniel and William Maloney, Does What You Export Matter? In Search of Empirical Guidance for Industrial Policies, Washington DC: The World Bank, 2012. , , and Luis Servén, Lessons from NAFTA for Latin America and the Caribbean, Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 2005. Levy, Santiago, Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes: Social Policy, Informality and Economic Growth in Mexico, Brookings Institution Press, Washington D.C., 2008. Lopez Cordova, Ernesto, “NAFTA and Manufacturing Productivity in Mexico,” Economia: Journal of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association, 2003, 4 (1), 55 – 88. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion References III , Alejandro Micco, and Danielken Molina, “How Sensitive Are Latin American Exports to Chinese Competition in the U.S. Market?,” Economia: Journal of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association, 2008, 8 (2), 117 –. Matsuyama, Kiminori, “Agricultural Productivity, Comparative Advantage, and Economic Growth,” Journal of Economic Theory, 1992, 58. Olley, G. Steven and Ariel Pakes, “The Dynamics of Productivity in the Telecommunications Industry,” Econometrica, 1996, 64 (6), 1263–1297. Prebisch, Raul, “The Economic Development of Latin America and its Principal Problems,” 1950. New York: United Nations, Reprinted in Economic Bulletin for Latin America in 1962. Utar, Hale and Luis B. Torres Ruiz, “International Competition and Industrial Evolution: Evidence from the Impact of Chinese Competition on Mexican Maquiladoras,” Journal of Development Economics, 2013, 105, 267 – 287. Verhoogen, Eric, “Trade, Quality Upgrading and Wage Inequality in the Mexican Manufacturing Sector,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2008, 123 (2), 489–530. NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Means by Sub-Sector: Apparel non-maquiladoras Employment non-exporters (1) exporters (2) maquiladoras (3) 260.19 (17.90) 0.02 (0.01) 64.96 (29.22) 0.15 (0.02) 84.66 (1.62) 7.25 (0.16) 2.34 (0.13) 5.50 (0.44) 55.17 (4.51) 4.91 (0.31) 460.66 (39.51) 46.93 (3.53) 0.05 (0.02) 48.38 (8.87) 0.18 (0.02) 82.91 (1.46) 7.40 (0.14) 2.43 (0.11) 6.38 (0.55) 60.19 (5.44) 4.45 (0.29) 813.88 (57.79) 97.40 (1.13) 0.60 (0.05) 28.90 (7.56) 0.14 (0.01) 88.48 (1.18) 7.21 (0.14) 3.03 (0.17) 6.84 (0.50) 60.20 (4.90) 3.29 (0.16) 112 105 111 Export percentage of sales Foreign ownership indicator Capital-labor ratio Share with >= 12 years schooling Percentage blue-collar Years of schooling, blue-collar Blue-collar hourly wage White-collar hourly wage Turnover rate Tenure (years) N Notes: Standard errors of means in parentheses. Sample is plants with ≥ 100 employees in 1999 ENESTyC. Capital-labor ratio measured in thousands of 1998 pesos; blue-collar and white-collar hourly wage in 1998 pesos. Average 1998 nominal exchange rate: 9.1 pesos/dollar. Return NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Means by Sub-Sector: Transportation Equipment non-maquiladoras Employment non-exporters (1) exporters (2) maquiladoras (3) 344.24 (46.90) 0.28 (0.07) 212.92 (90.57) 0.27 (0.02) 75.35 (1.89) 7.79 (0.19) 3.55 (0.26) 7.24 (0.61) 45.99 (7.59) 5.37 (0.34) 637.01 (52.91) 41.32 (2.68) 0.49 (0.04) 294.49 (46.77) 0.34 (0.02) 73.40 (1.01) 8.60 (0.12) 4.73 (0.22) 11.17 (0.52) 33.11 (3.18) 6.88 (0.28) 1342.07 (82.97) 96.33 (1.28) 0.97 (0.02) 57.30 (22.49) 0.20 (0.01) 84.29 (1.48) 7.43 (0.14) 3.64 (0.19) 9.81 (0.65) 69.47 (6.74) 3.74 (0.20) 46 141 92 Export percentage of sales Foreign ownership indicator Capital-labor ratio Share with >= 12 years schooling Percentage blue-collar Years of schooling, blue-collar Blue-collar hourly wage White-collar hourly wage Turnover rate Tenure (years) N Notes: Standard errors of means in parentheses. Sample is plants with ≥ 100 employees in 1999 ENESTyC. Capital-labor ratio measured in thousands of 1998 pesos; blue-collar and white-collar hourly wage in 1998 pesos. Average 1998 nominal exchange rate: 9.1 pesos/dollar. Return NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation Conclusion Means by Sub-Sector: Electrical/Electronic Equipment non-maquiladoras Employment non-exporters (1) exporters (2) maquiladoras (3) 334.83 (105.70) 0.25 (0.09) 132.03 (74.50) 0.29 (0.04) 73.35 (3.56) 8.03 (0.27) 3.04 (0.25) 8.74 (1.00) 39.68 (5.52) 6.18 (0.64) 585.75 (56.59) 39.94 (3.33) 0.52 (0.05) 223.10 (26.16) 0.31 (0.02) 71.88 (1.57) 8.52 (0.12) 3.84 (0.17) 10.17 (0.53) 41.19 (4.09) 6.21 (0.29) 1081.90 (51.35) 98.24 (0.78) 0.92 (0.02) 68.35 (14.69) 0.22 (0.01) 80.79 (1.06) 7.54 (0.09) 4.15 (0.17) 10.82 (0.48) 73.60 (4.56) 3.50 (0.12) 24 109 191 Export percentage of sales Foreign ownership indicator Capital-labor ratio Share with >= 12 years schooling Percentage blue-collar Years of schooling, blue-collar Blue-collar hourly wage White-collar hourly wage Turnover rate Tenure (years) N Notes: Standard errors of means in parentheses. Sample is plants with ≥ 100 employees in 1999 ENESTyC. Capital-labor ratio measured in thousands of 1998 pesos; blue-collar and white-collar hourly wage in 1998 pesos. Average 1998 nominal exchange rate: 9.1 pesos/dollar. Return NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development Eric Verhoogen Introduction Existing Approaches Sectoral Shifts and Innovation US Import Shares fromHanson: China, Mexico Why Isn’t Mexico Rich? Conclusion 1001 0.1 Mexico China 0.08 0.06 0.04 0.02 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 Year Figure 2: Share of U.S. Manufacturing Imports Source: Hanson (2010). Return comparative advantage in another third of its products (including automobiles and auto parts, industrial machinery, and ­beverages). NAFTA and Mexican Industrial Development (2010) take a more theoretical approach, introducing Ricardian productivity differences into a Marc J. Melitz (2003) model Eric Verhoogen The increasing similarity between the Chinese and Latin America export baskets is not unlike the Introductiongrowth in the similarity Existing Approaches and Figure Innovation between East Asia (China excluded) Sectoral and LatinShifts America. 5.2 shows the Conclusion ESI values between selected Latin American countries and regions and East Asia. The similarity of exports between Latin America (particularly Brazil and Mexico) and East Asian economies was relatively pronounced in the early-1990s; this similarity has increased during the same period, particularly for Mexico and Latin America as a whole.6 Export Similarity between Mexico and China Figure 5.2 Export Similarity between Selected Latin American Countries and East Asia in the US Market, 1992-2002 45 40 35 Percent 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Latin America Argentina 1992 Brazil Chile 1995 Colombia 2000 Mexico Central America 2002 Source: IDB-INT calculations based on UN/Comtrade data. Within manufacturing product categories, moreover, China’s export prices (measured in unit values) are generally lower and thanRodriguez-Clare the prices received by other developing economies in Latin America Source: Devlin, Estevadeordal (2006). and Asia. The premium received by those countries over China is highest in machinery and lowest in Return apparel. One explanation for this differential is that products from those regions offer higher quality or have more attributes than products from China, thereby raising their value. This would be consistent with differences in comparative advantage: countries that are relatively abundant in human NAFTA andand Mexican Industrial Development physical capital can improve quality or add product features. A competing explanation is that the Eric Verhoogen