Name ______________________________

Date __________

Social Studies 9

Period ________

Julius Caesar: Was he an effective leader?

Background: There have been whispers around the Roman senate that Caesar is proving not to

be an effective leader and he needs to be killed.

Task: Write a persuasive "secret" letter to the Roman senate conspirators either persuading them

that Caesar is ineffective and should be killed; or dissuading them by affirming his leadership and

keeping Caesar in power.

Audience: A group of Roman senators conspiring against Caesar.

Purpose: Your job is to utilize the sources attached and take a position. You are writing to those in

the Senate conspiring against Caesar. As a senator, you will take the position of either persuading

the conspirators to murder Caesar or dissuading them from murder and keep Caesar in power.

Procedure: After reading and reviewing the source materials. You are to write a five paragraph essay

on this topic in which you decide whether or not Caesar is an effective leader, furthermore should he

be killed or saved. Your letter (essay) should include an opening paragraph, three body paragraphs and

a concluding paragraph. Each body paragraph needs to include support from the provided sources.

Each paragraph should bet at least 5 sentences.

Resources: The resources are attached.

Skill: Develop a persuasive essay and persuasive skills. Using quotes from the source material.

Learning how to credit or discredit a position. Writing a five paragraph essay.

Document #1

Caesar, Gaius Julius (100?-44 B.C.)

Julius Caesar was a remarkable man who rose to supreme power in the Roman Republic.

He was witty, charming, generous, keenly intelligent, and a talented orator and writer. He

was also a cunning politician and a brilliant but ruthless military leader. Although he

never wore a crown, he laid the foundation for the Roman Empire. His very name,

Caesar, became the title of Roman emperors.

Early Years and Career

Caesar was probably born on July 13, 100 B.C. He belonged to a noble Roman family

whose declining fortunes were improved by successful marriages. His aunt Julia married

the popular general Marius. Caesar's first wife, Cornelia, was a daughter of Marius' ally

Cinna. After the deaths of Marius and Cinna, however, their supporters were defeated by

the Roman general Sulla. Caesar was forced into virtual exile in 81 B.C.

Caesar returned to Rome after Sulla's death in 78 B.C. He began his climb to power by

winning election to political office. He won additional elections by emphasizing his

connections with the dead hero Marius and by sponsoring public games.

Consul, Governor, and General

Sulla's old friends tried to block Caesar's career. However, he outwitted them by getting

the popular general Pompey and the wealthy noble Crassus to back his election as consul

in 59 B.C. The three men then forged an alliance to further their political ambitions. This

alliance was known as the First Triumvirate ("rule of three").

Caesar obtained the governorship of the Roman provinces Illyricum (on the coast of the

Adriatic Sea), Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy), and the Narbonese (southeastern France).

During this period he won great glory and wealth, conquering the Gauls and twice

invading Britain (55 and 54 B.C.). Caesar was not a professional soldier. But he combined

speed and daring to achieve his victories. He earned the fierce loyalty of his troops. His

Commentaries on the Gallic War is considered a model of clear, precise Latin prose.

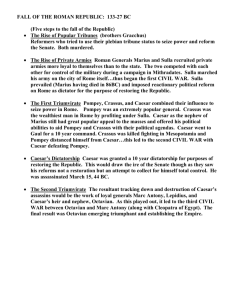

Crossing the Rubicon

Pompey, meanwhile, became jealous of Caesar's successes. He joined Caesar's enemies

in the Roman Senate in an attempt to deprive Caesar of his armies and to prevent his

election to a second consulship. In 49 B.C., Caesar took the momentous step of leading his

troops across the Rubicon, the river separating Cisalpine Gaul from Italy proper. This

was illegal under Roman law. And it began a civil war that soon engulfed most of the

empire.

Caesar quickly captured Rome. Pompey fled to Greece, where Caesar finally defeated

him at the Battle of Pharsalus (48 B.C.). Pompey again escaped, this time to Egypt, but he

was murdered before Caesar could reach him. In Egypt, politics and personal attraction

allied Caesar with the young princess Cleopatra. He made her queen of Egypt before he

left for a swift campaign against rebels in Asia Minor. See the article on Cleopatra.

Dictator of Rome

Caesar returned in triumph to Rome in 45 B.C. and was named dictator. He gave Roman

citizenship to many Gauls and appointed old political enemies to important posts. He

hoped that such kindness and generosity would gain him friendship and loyalty. His

numerous reforms included a revised calendar (the Julian calendar). He also improved

governmental efficiency, promoted education, increased employment, and gave land to

poor farmers.

Caesar went too far, however, when he accepted appointment as dictator for life in 44

B.C. This meant the end of the Roman Republic. Old friends and enemies alike conspired

to kill him. On March 15 (the Ides of March), 44 B.C., while at a meeting of the Senate,

he was attacked and stabbed to death.

Allen M. Ward

University of Connecticut

Coauthor, A History of the Roman People

How to cite this article:

MLA (Modern Language Association) style:

Ward, Allen M. "Caesar, Gaius Julius." The New Book of Knowledge. 2009.

Grolier Online. 20 Oct. 2009 <http://nbk.grolier.com/cgibin/article?assetid=a2004190-h>.

Chicago Manual of Style:

Ward, Allen M. "Caesar, Gaius Julius." The New Book of Knowledge. Grolier

Online. 2009. http://nbk.grolier.com/cgi-bin/article?assetid=a2004190-h (accessed

October 20, 2009).

APA (American Psychological Association) style:

Ward, A. M. (2009). Caesar, Gaius Julius. In The New Book of Knowledge.

Retrieved October 20, 2009, from Grolier Online http://nbk.grolier.com/cgibin/article?assetid=a2004190-h

Source: The New Book of Knowledge

™ & © 2009 Scholastic Inc. All rights reserved.

Document #2

A Monarch Uncrowned: Caesar, understanding the distasteful

symbolism of a coronation, publicly refused a crown that Mark

Antony tried to give him. It was probably a publicity stunt since

Caesar had made himself a monarch in everything but name.

Source Citation:Bonta, Steve. "The rise of Caesarism: the weakened Roman Republic was crushed by Julius Caesar, a charismatic military leader who

exploited his popularity with a Roman people who desired security above all else." The New American 21.1 (Jan 10, 2005): 34(6). General

OneFile. Gale. Stamford High School. 22 Oct. 2009

<http://find.galegroup.com/gps/start.do?prodId=IPS>.

Document #3

Caesar, Julius (100–44 B.C.)

Caesar, Julius (100–44 B.C.), one of the most famous men of antiquity who was dictator

of Rome, a renowned general, and man of letters.

Gaius Julius Caesar was born on July 12, 100 B.C. His family, the gens Julia, was

ancient and patrician, but at the time of his birth it was only beginning to reemerge as an

influential family in Roman politics. Caesar's aunt Julia married Marius, the successful

general and leader of the Popularis party. Caesar's anti-Senatorial attitude was at least

partially the result of his relationship to Marius.

Early Career

Caesar went in 81 to the province of Asia. Later he served under the proconsul of

Cilicia, but in 78, after he heard of Sulla's death, he returned to Rome. In Rome he

sought popularity through his oratory in the law courts; and finally, to improve his

oratory, he left Rome again in 75 and went to Rhodes to study under the famous

rhetorician Apollonius Molon.

Nothing of great historical significance happened to him after that until his election to

the quaestorship in 69 (for the year 68). He served in Farther Spain. In 66, Caesar ran for

the aedileship, and his campaign was financed by one of the richest and most powerful

men in Rome, Crassus. As aedile, Caesar was responsible for supervising the public

games, and with Crassus' money he sponsored spectacular contests to gain the favor of

the populace. In 63 he was elected pontifex maximus. Then, in 62, he became praetor. In

61, Caesar became propraetor of Farther Spain, and after some military expeditions he

returned to Rome to celebrate a triumph and run for the consulship.

The First Triumvirate

This was the great turning point in his career. According to Roman law a general had to

stay outside the city until the day of his triumph, but a candidate for the consulship had

to present himself before the magistrates in the city. Caesar asked permission to stand

for the consulship while remaining outside Rome so that he could celebrate his triumph.

The Senate refused. Caesar then gave up his triumph to seek the consulship, but he was

now alienated from the Senate. He began to negotiate with Pompey the Great, who was

seeking land for his veterans and ratification of the arrangements he had made in the east

after his successful campaign against Mithridates. The Senate had also alienated Pompey

by refusing his requests. Crassus, who had recently been rebuffed by the Senate, joined

Caesar and Pompey. The three formed an unofficial political coalition, called the First

Triumvirate, and decided to control Roman politics. Pompey could provide the soldiers

and Crassus the money, and Caesar had popularity.

In 59, Caesar aquired additional territories after the death of the governor of Transalpine

Gaul. The acquisition of these provinces was of great advantage to Caesar. It gave him

an opportunity to recruit and train an army, and he would be in an ideal location to

march on Rome whenever he wished. Until this time he had had only popularity;

henceforth he had popularity and armed might.

The Gallic Wars

For the next eight years (58–51) Caesar was occupied by the Gallic Wars, although he

was always in close contact with developments in Rome. By 51, except for occasional

local rebellions, the conquest of Gaul was complete. Caesar's army was highly trained

and well disciplined and fanatically loyal to him. His military exploits, particularly the

invasion of Britain, made him even more popular with the people.

The Dissolution of the Triumvirate

Meanwhile in Rome political events of great magnitude were taking place. The First

Triumvirate was falling apart because of the quarrels of Pompey and Crassus. There was

rioting in the city, and members of the Senate were beginning to attack Caesar.

Therefore, in 56 he called a meeting of the First Triumvirate in the city of Luca (now

Lucca) in his own province of Cisalpine Gaul. The triumvirs met secretly, patched up

the Triumvirate, and made certain decisions that were to determine the fate of the

Roman republic.

It was agreed that Pompey and Crassus should be consuls in 55, and afterward Pompey

was to receive the two Spains as his provinces, while Crassus would get Syria. Each of

them received his provincial commands for a five-year period. Caesar's own commands

were extended for five years (until March 1, 50). Pompey was given the privilege of

remaining in Italy and governing his Spanish provinces through legates.

At this point the First Triumvirate seemed to be strong again. But the appearance was

deceptive. In 54, Julia, Pompey's wife and Caesar's daughter, died, and one real bond

between the two men was lost. In the following year Crassus was killed at the Battle of

Carrhae, during his attempted invasion of the Parthian Empire. Only Caesar and Pompey

remained, and the senators at Rome immediately began to drive a wedge between them.

Because of rioting in the city it was impossible to hold the consular elections for the year

52. The Senate, which preferred Pompey to Caesar, secured a sole consulship for

Pompey and gave him extraordinary powers to protect the city. At this time Julius

Caesar was concerned about a constitutional matter: his command in Gaul was coming

to an end, and he did not want to lay it down to become a private citizen. If he did so, he

would be liable to prosecution in the courts for any illegal acts he had committed as a

magistrate, but as long as he held public office he could not be sued. He wanted to be

elected to a second consulship while he was still proconsul of Gaul. However the

holding of both offices was illegal.

Pompey was moving more and more into an alliance with the senatorial faction. To

avoid war, Caesar made one last offer to lay down his command if Pompey would also.

This was again refused, and on January 10, Caesar crossed the Rubicon, the river that

separated his province from Italy, and the Civil War began. Caesar is reputed to have

said, "The die is cast."

Civil War

Caesar moved with lightning rapidity down the east coast of Italy. He took Picenum and

Corfinium while Pompey withdrew with his entire force to Brundisium and sailed to

Greece. Almost overnight, Caesar became the master of Italy. But he was by no means

in an enviable position. Pompey controlled Spain on one side of Italy and secured a

stable base in Greece on the other side. In addition he had control of the sea. Caesar was

virtually surrounded.

He decided to strike first at Pompeian forces in Spain. After a short but difficult

campaign he was successful and finally could begin plans to defeat Pompey in Greece.

Early in 48 he sailed across the Adriatic and faced Pompey at Dyrrhachium. But

Pompey cut off his supplies, and after several difficult weeks Caesar was forced to break

away and head east toward Thessaly, where he could feed his army.

Pompey followed and camped opposite Caesar at Pharsalus. In the battle that followed,

Caesar was victorious, and Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was murdered by the

Egyptians. Caesar arrived three days later to find Egypt in political chaos. The young

Ptolemy XIII and his advisers were quarreling with his sister Cleopatra. Ptolemy's

advisers turned against Caesar and besieged him in the palace quarters of Alexandria

during the winter of 48–47. Caesar championed Cleopatra's cause, and when his

reinforcements arrived, he defeated Ptolemy. Cleopatra became the real ruler of Egypt.

Caesar lingered with her for a while, obviously enchanted by her charms, but eventually

he had to leave for Asia Minor where Pharnaces, the son of Mithridates, was in revolt.

Caesar defeated him within five days; this victory was the occasion for his famous

"Veni, vidi, vici" ("I came, I saw, I conquered").

The Consolidation of Victory

Throughout this period and in the few months remaining to him after his final victory

over the Pompeian forces, despite his preoccupation with warfare he effected numerous

reforms in Rome and Italy. In 46 he reformed the Roman calendar; the Julian calendar is

still the basis of our calendar today. To ease economic burdens, he remitted

approximately one quarter of the principal of debts, and later all of the interest that had

accrued since the beginning of the Civil War. He cut the number of citizens eligible for

the grain dole from 320,000 to 150,000. He inaugurated a building program and passed

laws to regulate traffic and open spaces and to provide for the upkeep of roads. The

system of taxation in some of the provinces was reformed, and Roman citizenship was

generously bestowed on many provinces. Colonies were founded for his veterans and

the surplus population of the city.

Personal Characteristics

Julius Caesar was one of the most remarkable men in antiquity or in any period. He was

a highly successful general. As a strategist and tactician he fell short of greatness, but he

made up for that with speed and boldness as well as courage. His ability as a statesman

did not have the opportunity to develop, but all signs indicate that he was extremely

sensitive to social and economic problems and was also bold enough to attempt new

solutions. As a politician, however, he became too overbearing. The poet Lucan

compared him to a bolt of lightning, saying, "Nothing may stand against it, either during

that furious progress through the clouds, or when it bursts against the earth and at once

recomposes its scattered fires."

Caesar is important not only as a statesman and a general, but also as a man of letters.

His Commentaries on the Gallic and Civil wars are still widely read today. They were

written in a very clear and direct prose style famous for its affected objectivity. In them

Caesar referred to himself as "he" or as "Caesar," but not as "I." The simplicity and

directness of their style have made the Commentaries popular with teachers of beginning

Latin classes. In the field of oratory he was regarded as second only to Cicero.

Arther Ferrill

University of Washington

How to cite this article:

MLA (Modern Language Association) style:

Ferrill, Arther. "Caesar, Julius (100–44 B.C.)." Encyclopedia Americana. 2009. Grolier

Online. 20 Oct. 2009 <http://ea.grolier.com/article?id=0070080-00>.

Document #4

Julius Caesar

Also known as: Gaius Julius Caesar

Born: July 12 or 13, 100 b.c.e.; Rome (now in Italy)

Died: March 15, 44 b.c.e.; Rome (now in Italy)

Life’s Work

It is impossible to tell if Caesar wished to destroy the last remnants of the old Republic

and replace it with a formal autocracy or whether he merely intended to become the

leading citizen—although one without rivals—in the Roman world. In the end, the result

was the same, for Caesar for a brief time did become supreme ruler, and the Republic was

destroyed. Although it was Caesar’s nephew and heir Octavian (later known as Augustus)

who became the first Roman emperor, it was Caesar who made the Empire possible.

In 61 b.c.e., Caesar was appointed governor of Farther Spain and honored with a triumph

for his military campaigns there. The next year, he was elected as one of the two consuls

who headed the Roman government; his term of office began in 59 b.c.e. The rest of

Caesar’s career stems, directly or indirectly, from this consulship.

As one of two consuls, Caesar had to deal with his colleague, a conservative opponent.

Impatient with this and other obstructions, Caesar initiated numerous highly irregular,

sometimes illegal, actions. These were designed to benefit Pompey’s discharged veterans,

increase the wealth of Crassus, and advance the general aims of the Triumvirate. So

blatant, however, were the offenses—including violence against officials whose positions

made them virtually sacred—that Caesar knew that his enemies would not rest until he

had been prosecuted, convicted, and condemned.

His only recourse was to remain in office, because then he would be immune from trial.

He secured the provinces of Cisalpine Gaul (now northern Italy) and Illyricum (the coast

of modern Yugoslavia) and soon added Transalpine Gaul (southern France), which

bordered on lands unconquered by Rome.

Caesar wasted no time in finding an excuse to wage war against the Gauls, and for the

next eight years he was embroiled in the Gallic Wars, which are vividly recounted in his

commentaries. During his campaigns, he crossed the Rhine River to drive back the

German tribes and twice launched an invasion of Britain. Although his attempts on the

island were unsuccessful, his second fleet numbered eight hundred ships—the largest

channel invasion armada until the Allied Normandy invasion in World War II.

In 52 b.c.e., the recently subdued Gauls revolted against the Romans and, led by

Vercingetorix, came close to undoing Caesar’s great conquests. By brilliant generalship

and extraordinary efforts, Caesar pinned the Gauls in their fortress town of Alesia

(Aliese-Sainte-Reine) and destroyed their army, finally ending the Gallic Wars.

According to Caesar, he had fought thirty battles, captured eight hundred towns, and

defeated three million enemies, of whom almost a million had been slain, another million

captured. Although these figures are surely exaggerated, they do illustrate the extent of

Caesar’s victory. Its long-lasting effect was the opening of northern Europe to the

influence of Greek and Roman culture and the rich heritage of the Mediterranean

civilization.

Returning to Rome, Caesar became dictator for the first time and proceeded to tackle

numerous social problems, especially that of widespread debt, caused by the breakdown

of the Republic. In 48 b.c.e., he daringly crossed the Adriatic Sea in winter and besieged

Pompey’s larger forces at their base of Dyrrachium (Durazzo). Forced to retire into

Thessaly, Caesar turned and defeated Pompey at the Battle of Pharsalus, destroying his

army. Pompey fled to Egypt, hoping to rally support, but instead was murdered; the

whole Roman world was in Caesar’s grasp.

Following Pompey to Egypt, Caesar intervened in a power struggle between Cleopatra

VII and her younger brother. In this, the Alexandrian War, Caesar narrowly escaped

death on several occasions but was successful in placing Cleopatra on the throne. There

followed an intense affair between the young queen and Caesar, and the son born in

September, 48 b.c.e., was named Caesarion.

After more campaigns against foreign states in the east and the remnants of Pompey’s

supporters, Caesar returned to Rome in 46 b.c.e. to celebrate four triumphs: over Gaul,

Egypt, Pontus, and Africa. Cleopatra arrived soon after to take up residence in the city;

perhaps along with her came the eminent Egyptian astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria,

who aided Caesar in his reform of the calendar. This Julian calendar is the basis of the

modern system.

Caesar was active in other areas. He settled many of his veterans in colonies throughout

the Empire, and with them many of the poor and unemployed of Rome, thus reducing the

strain on the public economy. Numerous other civic reforms were instituted, many of

them laudable, but most of them giving increased power to Caesar alone. Although he

publicly rejected the offer of kingship, he did accept the dictatorship for life in February,

44 b.c.e.

This action brought together a group of about sixty conspirators, led by Cassius and

Marcus Junius Brutus. Brutus may have been Caesar’s son; certainly he was an avowed,

almost fanatic devotee of the Republic who thought it his duty to kill Caesar.

Realizing that Caesar planned to depart on March 18 for a lengthy campaign against the

Parthian Empire in the east, the conspirators decided to strike. On March 15, the ides of

March, they attacked Caesar as he entered the Theater of Pompey for a meeting of the

senate. As he fell, mortally wounded, his last words are reported to have been either “Et

tu, Brute?” (and you too, Brutus?) or, in Greek, “And you too, my child?”

Significance

“Veni, vidi, vinci”—“I came, I saw, I conquered”—is one of the most famous military

dispatches of all time, and totally characteristic of Julius Caesar. He sent it to Rome after

his defeat of King Pharnaces of Pontus in 47 b.c.e., a campaign that added greatly to

Rome’s eastern power but which represented almost an interlude between Caesar’s

victories in Egypt and his final triumph in the civil war. The message captures the

essence of Caesar, that almost superhuman mix of energy, ability, and ambition.

This mixture fascinated his contemporaries and has enthralled the world ever since.

Caesar was ambitious, but so were others, Pompey among them. He was bold, but many

other bold Romans had their schemes come to nothing. He was certainly able, but the

Roman world was full of men of ability.

It was Caesar, however, who united all these qualities and had them in so much fuller

measure than his contemporaries that he was unique. As a writer or speaker, he could

easily hold his own against acknowledged masters such as Cicero; in statesmanship and

politics, he was unsurpassed; in military skill, he had no peer. When all of these qualities

were brought together, they amounted to an almost transcendent genius that seemed to

give Julius Caesar powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men.

The central question, in 44 b.c.e. and today, is to what use—good or bad—did Caesar put

those qualities and abilities? Clearly, Brutus, Cassius, and the other conspirators believed

that he had perverted his qualities and subverted the state and thus must be destroyed. In

later years, the term “Caesarism” has been applied to those who wished to gain supreme

power for themselves, disregarding the laws and careless of the rights of others. Viewed

from this perspective, Caesar destroyed the last remnants of the Roman Republic and thus

stamped out what liberty and freedom remained.

From another view, he was the creator, or at least the forerunner, of a new and better

system, the Empire, which brought order from chaos, peace from endless civil war. The

ancient Republic had already disappeared in all but name, had become empty form

without real substance, and it was for the general good that it finally disappeared. This is

the view of Caesar as archetypal ruler and dispenser of order, the view that made his very

name a title of monarchs—the Caesars of Rome, the kaisers of Germany, the czars of

Russia.

Essay by: Michael Witkoski

"Julius Caesar." Great Lives from History: The Ancient World, Prehistory–476 c.e

(2004): Literary Reference Center. EBSCO. Web. 19 Oct. 2009.

Document #5

Following his years in Gaul, Julius Caesar returned to Rome in 49. In direct disobedience of the

Roman Senate, he refused to disband his army and crossed with them into Italy. From there, he

marched on Rome, looking for a showdown with Pompey and his supporters in the Senate, to

fight for the control of the empire. While Caesar sent part of his army into Spain, he himself

pursued Pompey, who had fled to Greece. Here, Pompey’s army suffered a defeat at Pharsalus in

48. After Pompey's death in Egypt, Caesar continued to consolidate his power, marching east

("Veni, vidi, vici"—"I came, I saw, I conquered," following his victory at Zela in modern Turkey)

in 47. Pompey's remaining forces were finally defeated at Munda, in Spain, in 45.

Text Citation: "Caesar's Routes in the Civil War, 49–45 BCE." Ancient and Medieval History

Online. Facts On File, Inc. http://www.fofweb.com/activelink2.asp?

ItemID=WE49&iPin=ammap187&SingleRecord=True (accessed October 22, 2009).

Media Citation: "Caesar's Routes in the Civil War, 49–45 BCE." Ancient and Medieval History

Online. Facts On File, Inc. http://www.fofweb.com/activelink2.asp?

ItemID=WE49&iPin=ammap187&SingleRecord=True (accessed October 22, 2009).

Document #6 (optional): Primary Source

LXXVI. Yet after all, his other actions and words so turn the scale, that it is thought that

he abused his power and was justly slain. For not only did he accept excessive honors,

such as an uninterrupted consulship, the dictatorship for life, and the censorship of public

morals, as well as the forename Imperator, the surname of Pater Patriae ['Father of his

Country'], a statue among those of the kings, and a raised couch in the orchestra [at the

theater]; but he also allowed honors to be bestowed on him which were too great for

mortal man: a golden throne in the Senate and on the judgment seat; a chariot and litter

[for carrying his statues among those of the gods] in the procession at the circus; temples,

altars, and statues beside those of the gods; a special priest, an additional college of the

Luperci, and the calling of one of the months by his name. In fact, there were no honors

which he did not receive or confer at pleasure. He held his third and fourth consulships in

name only, content with the power of the dictatorship conferred on him at the same time

as the consulships. Moreover, in both years he substituted two consuls for himself for the

last three months, in the meantime holding no elections except for tribunes and plebeian

aediles, and appointing praefects instead of the praetors, to manage the affairs of the city

during his absence. When one of the consuls suddenly died the day before the Kalends of

January, he gave the vacant office for a few hours to a man who asked for it. With the

same disregard of law and precedent he named magistrates for several years to come,

bestowed the emblems of consular rank on ten ex-praetors, and admitted to the Senate

men who had been given citizenship, and in some cases half-civilized Gauls. He assigned

the charge of the mint and of the public revenues to his own slaves, and gave the

oversight and command of the three legions which he had left at Alexandria to a favorite

of his called Rufo, son of one of his freedmen.

LXXVII. No less arrogant were his public utterances, which Titus Ampius records: that

the state was nothing, a mere name without body or form; that Sulla did not know his

ABC's when he laid down his dictatorship; that men ought now to be more circumspect in

addressing him, and to regard his word as law. So far did he go in his presumption, that

when a soothsayer once reported of a sacrifice direful innards without a heart, he said:

"They will be more favorable when I wish it; it should not be regarded as a portent, if a

beast has no heart" [playing on the double meaning of cor ('heart')--which was also

regarded as the seat of intelligence].

LXXVIII. But it was the following action in particular that roused deadly hatred against

him. When the Senate approached him in a body with many highly honorary decrees, he

received them before the temple of Venus Genetrix without rising. Some think that when

he attempted to get up, he was held back by Cornelius Balbus; others, that he made no

such move at all, but on the contrary frowned angrily on Gaius Trebatius when he

suggested that he should rise. And this action of his seemed the more intolerable, because

when he himself in one of his triumphal processions rode past the benches of the tribunes,

he was so incensed because a member of the college, Pontius Aquila by name, did not

rise, that he cried: "Come then, Aquila, take back the republic from me, you tribune"; and

for several days he would not make a promise to any one without adding, "That is, if

Pontius Aquila will allow me."

Source:From: Suetonius, 2 vols., trans. J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann,

1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119 Scanned by: J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton. Prof. Arkenberg has modernized the text.