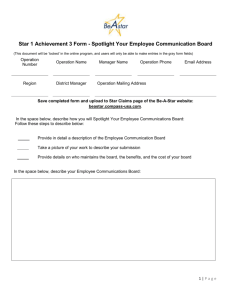

The spotlight effect in a marketing context Overestimating brand

advertisement