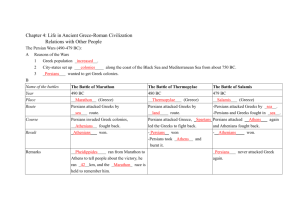

The Persian Wars

advertisement

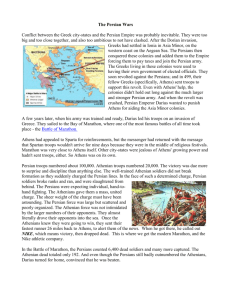

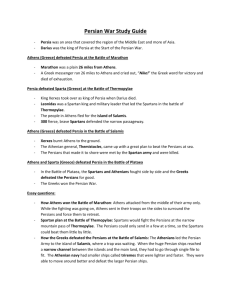

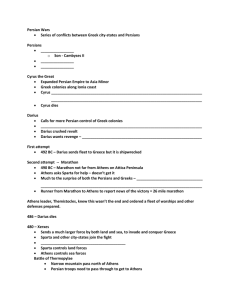

The Persian Wars 500 B.C. – 479 B.C. The Beginning Darius, king of the Persians, came to power and continued to extend the Persian Empire across Asia Minor. The Persians had already taken control of most Greek colonies, and Darius would conquer Ionia (ī-ō'nē-ə), a Greek sister state. Feeling threatened, the two strongest Greek city states, Sparta and Athens, encouraged the Ionians to revolt. Darius would eventually crush the Ionian revolt in 495 B.C. He would then turn his attention to the Greek mainland to seek revenge on Athens and Sparta. The Battle of Marathon Darius sent a great army, with an estimated size of 20,000 soldiers, over the sea to the Bay of Marathon, intending to land there, march to Athens and then on to Sparta. Miltiades (mil-tahy-uhdeez), the Athenian general, marched an army of 10,000 men out of Athens, hoping to delay the Persians until reinforcements were sent from Sparta. Professional runner, Pheidippides (fahy-dip-ideez), ran 250 km in two days to Sparta and back to ask the Spartans for their support against the Persians. The Spartans said they could not help until after the next full moon for religious reasons Greatly outnumbered, the Athenians took advantage of the Persians’ overconfidence and their knowledge of the terrain. The strategy: The Persians put their best troops in the centre, the Athenians put their best troops on the side. The battle: The Persians broke through the weak Athenian centre but were pushed back on the wings by the superior Athenian troops. The Persians were surrounded and defeated. The remaining Persians returned to their ships and attempted to reach Athens. Miltiades (mil-tahy-uh-deez), however, marched his army overland to meet them and the Persians dared not come ashore. The Persian invasion thus failed. Legend has it that Pheidippides (fahy-dipi-deez) ran the 42 km back to Athens to announce their great victory and died on the spot. Today’s marathon is based on this last run by Pheidippides. The Battle of Thermopylae (ther-mop-uh-lee) There was fear the Persians might return. Under Themistocles (thuh-mis-tuh-kleez), the Athenians developed a strong navy of 200 triremes (boats). In 485 B.C., Xerxes (zurkseez) succeeded his father, Darius, as king of the Persians. He vowed revenge on the Greeks. Xerxes (zurk-seez) sent a huge army and navy to attack the Greek mainland once again (180,000 troops). Xerxes’ army advanced along the Greek coast until coming to Themopylae, a fifty foot wide mountain pass. The strategy: The Spartan king, Leonidas (lee-on-i-duhs), and 7000 men wanted to hold the Persians at the pass. The battle: The Persians attacks were repulsed until a traitor showed the Persians a secret path. 300 Spartan elders and 1,000 men stayed behind to allow the other Greeks time to fall back and mount defenses. All died, but 20,000 Persians were also killed. The Battle of Salamis (sah-lah-mees) As the Persians advanced after their victory at Thermopylae (ther-mopuh-lee), Athens was evacuated. The Athenians escaped to the island of Salamis, off the coast of Athens. The Persian army sacked and burned Athens. Themistocles (thuh-mis-tuh-kleez) ordered all Greek men onto the triremes and set sail into the Straits of Salamis. The strategy: The Greeks wanted to lure the Persians into the narrow waters of Straits of Salamis, which they knew better. Themistocles sent his servant with false information to Xerxes, claiming the Greeks would attempt to escape through the Straits. Xerxes, eager for victory, believed the message. The battle: The Persians sailed into the Straits of Salamis, and were trapped by the Greeks. The Greeks were outnumbered, but swift and deadly Athenian triremes defeated the Persian navy. The End The remainder of the Persian army was defeated by the Spartans at Plataea (pluh-tee-uh) and the rest of the Persian fleet was caught beached on shores of Asia Minor and destroyed by the Greeks. This twenty year battle had ended in an astonishing victory for the Greeks and it filled them with pride, confidence, and patriotism, leading to the Golden Age.