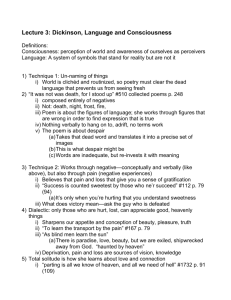

Abhidhamma Studies

advertisement