genderlect styles

advertisement

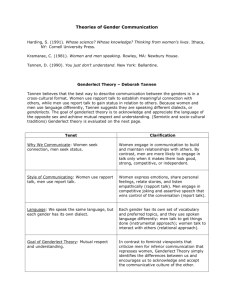

CHAPTER 33 GENDERLECT STYLES Outline I. Introduction. A. Deborah Tannen argues that male-female communication is cross-cultural. B. Miscommunication between men and women is both common and insidious because the parties usually don’t realize that the encounters are cross-cultural. C. Tannen’s writing underscores the mutually alien nature of male and female conversation styles. D. Tannen’s approach departs from much feminist scholarship that claims that conversations between men and women reflect male domination. 1. She assumes that male and female conversational styles are equally valid. 2. The term genderlect suggests that masculine and feminine styles of discourse are best viewed as two distinct cultural dialects rather than as inferior or superior ways of speaking. E. At the risk of reinforcing a reductive biological determinism, Tannen insists that there are gender differences in the ways we speak. II. Women’s desire for connection versus men’s desire for status. A. More than anything else, women seek human connection. B. Men are concerned mainly with status. C. Tannen does not believe that men and women seek only status and connection, respectively, but these are their primary goals. III. Rapport talk versus report talk. A. Public speaking versus private speaking. 1. Women talk more than men in private conversations. 2. In the public arena, men vie for ascendancy and speak much more than women. 3. Men assume a lecture style to establish a “one-up” position, command attention, convey information, and insist on agreement. 4. Men’s monologue style is appropriate for report, but not for rapport. B. Telling a story. 1. Men tell more stories and jokes than do women. 2. Telling jokes is a masculine way to negotiate status. 3. Men are the heroes in their own stories. 4. When women tell stories, they downplay themselves. C. Listening. 1. Women show attentiveness through verbal and nonverbal cues. 2. Men may avoid these cues to keep from appearing “one-down.” 3. A woman interrupts to show agreement, to give support, or to supply what she thinks the speaker will say (a cooperative overlap). 4. Men regard any interruption as a power move. 446 D. Asking questions. 1. Men don’t ask for help because it exposes their ignorance. 2. Women ask questions to establish a connection with others. 3. When women state their opinions, they often use tag questions to soften the sting of potential disagreement and to invite participation in open, friendly dialogue. E. Conflict. 1. Men usually initiate and are more comfortable with conflict. 2. To women, conflict is a threat to connection to be avoided at all costs. 3. Men are extremely wary about being told what to do. IV. “Now you’re beginning to understand.” A. Tannen believes that both men and women need to learn how to adopt the other’s voice. B. However, she expresses only guarded hope that men and women will alter their linguistic styles. C. She has more confidence in the benefits of multicultural understanding between men and women. V. Critique: is Tannen soft on research and men? A. Tannen suggests we use the “aha factor”—a subjective standard of validity—to test her truth claims. B. Tannen’s analysis of common misunderstandings between men and women has struck a chord with millions of readers. C. Critics suggest that selective data may be the only way to support a reductionist claim that women are one way and men another. D. Tannen’s intimacy/independence dichotomy echoes one of Baxter and Montgomery’s tensions, but it suggests none of the ongoing complexity of human existence that relational dialectics describes. E. Tannen’s assertions about male and female styles run the risk of becoming selffulfilling prophecy. F. Ken Burke, Nancy Burroughs-Denhart, and Glen McClish suggest that although Tannen claims both female and male styles are equally valid, many of her comments and examples tend to disparage masculine values. G. Julia Wood and Christopher Inman observe that the prevailing ideology of intimacy discounts the ways that men draw close to each other. H. Adrianne Kunkel and Brant Burleson challenge the different cultures perspective that is at the heart of Tannen’s genderlect theory, citing their work on comforting as equally valuable to both sexes. I. Senta Troemel-Ploetz accuses Tannen of ignoring issues of male dominance, control, power, sexism, discrimination, sexual harassment, and verbal insults. 1. You cannot omit issues of power from communication. 2. Men understand what women want but give it only when it suits them. 3. Tannen’s theory should be tested to see if men who read her book talk more empathetically with their wives. 447 Key Names and Terms Deborah Tannen A linguist at Georgetown University who has pioneered research in genderlect styles. Genderlect A term that suggests that masculine and feminine styles of discourse are best viewed as two distinct cultural dialects and not inferior or superior ways of speaking. You Just Don’t Understand Tannen’s best-seller, which presents genderlects styles to a popular audience. Rapport Talk The conversational style Tannen associates with women, which seeks to establish connection. Report Talk The conversational style Tannen associates with men, which seeks to command attention, convey information, and insist on agreement. Cooperative Overlap When a woman interrupts to add words of agreement, to show support, or to finish a sentence with what she thinks the speaker will say. It is a sign of rapport rather than a competitive ploy. Tag Question A short question at the end of a declarative statement, often used by women to soften the sting of potential disagreement and to invite participation in open, friendly dialogue. Aha Factor A subjective standard ascribing validity to an idea when it resonates with one’s personal experience. Ken Burke, Nancy Burroughs-Denhart, and Glen McClish Communication scholars who suggest that although Tannen claims both female and male styles are equally valid, many of her comments and examples tend to disparage masculine values. Julia Wood and Christopher Inman Communication scholars from the University of North Carolina who observe that the prevailing ideology of intimacy discounts the ways that men draw close to each other. Adrianne Kunkel and Brant Burleson Communication scholars from the University of Kansas and Purdue University, respectively, who challenge the different cultures perspective based on results from their research on comforting. Senta Troemel-Ploetz A German linguist and feminist who accuses Tannen of ignoring issues of male dominance, control, power, sexism, discrimination, sexual harassment, and verbal insults. 448 Principal Changes Griffin has changed the section on conflict to better align it with Tannen’s thinking, added Kunkel and Burleson’s objection to the Critique section, and has updated the Second Look section. Suggestions for Discussion Of all the theorists featured in A First Look at Communication Theory, Deborah Tannen is the only one who qualifies as a genuine celebrity in contemporary popular culture—a fact conclusively proven by the cartoon on page 477. She is quoted, praised, and criticized everywhere you turn. Indeed, the “aha factor” has been a reality for millions of Americans, and you’ll have no trouble interesting your students in this provocative, germane material. Sex and gender: a very important distinction Although they are often used synonymously, sex and gender are not the same and it’s a point worth making at the onset of the discussion of the gender theories. As Griffin points out in the introduction to this section (469), sex is an objective fact based on biological criteria while gender is a social, symbolic creation learned through cultural training. Put in the vernacular, sex is about the hardware and gender the software. To say that a true sex difference exists is to imply that a difference between men and women is somehow linked to biological or chromosomal differences. For example, there is a true sex difference between men and women in physical strength based on differing muscle potency. However, to say that something is a gender difference suggests that the discrepancy is not related to biology, but to a culturally learned, cognitive construction. Therefore, genderlects is an apt title for Tannen’s position, though the point becomes distorted because distinctions are drawn between males and females, biological-based terms, when it would be more appropriate to label the two camps by their gender-based titles—masculine and feminine. How much of a difference is this difference? As with any claim that any single factor makes an enormous difference, the conscientious student of communication theory must ask how much of the variability can be explained. In her theory, Tannen claims that gender differences make all the difference, a point you may want to discuss with your students. To use Julia Woods’s terminology, is Tannen “essentializing” or implying that all members of a sex are essentially the same? But, as Griffin points out in his section introduction (467-69), other researchers have suggested that great variability exists within the members of each sex and furthermore, much similarity exists between the two camps. You may want to discuss Kathryn Dindia and Mike Allen’s metaanalysis (“Sex Differences in Self-Disclosure: A Meta-Analysis,” Psychological Bulletin 112, 1 [1992], 106-124), which found a -.01 correlation between men and women on self-disclosure, a finding that clearly challenges Tannen’s claim of a vast divide. 449 The merit in being attacked on all sides In the previous chapter on speech codes, Griffin gives Philipsen some profound praise when he suggests that important theories are widely attacked. Quoting his own professor, Griffin says, “You know you’re in the wrong place on an issue if you aren’t getting well roasted from all sides” (463). It’s important to show your students that this “golden mean” standard also applies to Tannen’s work. As Griffin’s Critique section succinctly demonstrates, she has been attacked both for being too tough on men and for being insufficiently tough on them. To some, she has unlocked the secrets of male-female communication, and to others she has locked us into the prison house of gender stereotypes. The point, it seems to us, is not to condemn her for this variety of responses, but to applaud her for stirring the thoughts and beliefs of so many people. Right, wrong, or somewhere in between, she has been a terrific catalyst for discussions of communication theory and methodology. The missing metamessage Tannen’s books are filled with many interesting ideas, and unfortunately Griffin had to cut much to keep this chapter an appropriate length. One of the most important excluded concepts is the “metamessage.” In both That’s Not What I Meant! and You Just Don’t Understand, Tannen suggests that women are more sensitive to the communicative power of context, whereas men tend to focus more narrowly on messages in isolation from situational factors. When misunderstandings arise over metamessages, women accuse men of being “insensitive” and men blame women for “reading things into” what they say. (One could argue, in fact, that interpretative differences concerning metamessages correspond to the different communicative styles of collectivistic and individualistic cultures as featured in Chapter 31. Tannen seems to be suggesting that whereas women’s culture is high context, men’s is low context.) The concept of the metamessage also relates closely to a key axiom of the interactional view (communication = content + relationship). You might consider adding differences in the interpretation of metamessages to the list of five major distinctions between male and female communication included in the section of the chapter titled “Rapport Talk versus Report Talk.” Unappreciated empathy At the beginning of the Critique section, Griffin covers the basic point that women are more likely to desire understanding than advice in conversation (478), but he is unable to include Tannen’s important counterpoint that men may not appreciate displays of empathy because they undermine their autonomy and the uniqueness of their particular problem (You Just Don’t Understand 51). Unlike women, men may not like their partners to say, “I know just how you feel.” It will be interesting to see how your class responds to this claim. Bateson’s “complementary schismogenesis”: A worsening spiral One of Tannen’s most useful concepts (featured in both That’s Not What I Meant! and You Just Don’t Understand) has been borrowed from Gregory Bateson—“complementary schismogenesis.” This notion aptly describes the worsening spiral of miscommunication that often frustrates men and women. Bateson’s electric-blanket analogy is priceless. 450 High involvement conversational style Perhaps the most underrated and provocative section of You Just Don’t Understand is Tannen’s discussion of the “high considerateness”/”high involvement” dichotomy in conversation (196-202). She suggests that some people who interrupt and overlap frequently aren’t being rude; they’re simply operating under the conversational norms of high involvement. What’s particularly interesting here is that Tannen attributes differences in communicative style to culture and geographical region, rather than gender, thus complicating her approach to conversational styles considerably. Genderlects as a self-fulfilling prophecy? Be sure your students understand Griffin’s point that Tannen’s theory could function as self-fulfilling prophecy (479). If self and gender are socially constructed, then the work of celebrity theorists such as Tannen can have a terrific impact on actual human development. In this sense, books that claim to reveal the “truth” about male or female patterns have the potential to become normative. If influential writers such as Tannen and John Gray—author of Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus: A Practical Guide for Improving Communication and Getting What You Want in Your Relationships (New York: HarperCollins, 1992) and several sequels—tell us that men and women invariably act in certain ways, then it is but a small step to believing that they should do so. How, then, should one view women professors who consistently put their careers ahead of relationships and friendships? More to the point, how should these women view themselves? Are they unfeminine or abnormal? Are husbands who put their wives ahead of their jobs effeminate? When does mere description become prescription? (An example of an explicit translation of description of gender differences into prescription is the popular and controversial book The Rules: Time-Tested Secrets for Capturing the Heart of Mr. Right, by Ellen Fein and Sherrie Schneider [New York: Warner Books, 1995.]) (Essay Questions #23 and #27 below address this issue.) Is genderlect theory ethnocentric? The critique of Burke, Burroughs-Denhart, and McClish that You Just Don’t Understand contains an implicit bias against the male style raises an issue that was initially brought up in our treatment of speech codes theory: the difficulty of comparing your own culture to another without inherently favoring that with which you are more familiar. Just as Philipsen could be seen to paint a more favorable picture of the communicative practices of Nacirema than those of Teamsterville, so Tannen may give a better impression of female conversation than its male counterpart. It’s a point worth considering. Another way to approach the issue would be to ask the following question: “What would You Just Don’t Understand be like if it had been written by a man?” With regard to Kunkel and Burleson’s claim that the different cultures perspective “has lost its narrative force” (479), we are reminded of a like-minded bumper sticker: “Men are from Earth, women are from Earth—Get used to it!” 451 Sample Application Log Nate The best example of a real difference between the need for connection and status is how my wife and I get into conflicts. I usually initiate arguments by bringing up things we need to work on, whereas my wife needs to know that everything is good right now. You see, I want to have the best relationship of anyone we know. My wife does want the same, but she thinks it should be that way to start off with—a difficult thing for a male communications student. Exercises and Activities Is genderlects outdated? Many of our students have suggested that distinct behavioral and communicative differences between the genders are more relics of the past than conditions of the present. In this era of relative gender equality, they claim, the kinds of dichotomies Tannen describes are primarily matters of history, rather than contemporary life. Challenge students to provide evidence for this “Brave New World” claim. (Essay Question #24, below, addresses this issue.) You might also want students to discuss how cultural factors intersect with gender to complicate Tannen’s claims. (See Essay Question #27 below.) Bem’s sex role inventory (BSRI) Before covering genderlects theory in class, consider asking your students to complete Sharon Lipsitz Bem’s sex role inventory that Griffin discusses in the gender section’s introduction (468). The inventory is based on evaluating how aptly or characteristically 60 adjectives are of one’s self and the tallied score indicates a person’s degree of masculinity and femininity, or amount of identification with a particular sex role. While some students may find themselves a perfect match between sex and sex role identification (i.e. the very masculine man or the ultra feminine woman), others may find themselves in a more undefined place, by either straddling neutral ground or by being extremely high or low in both masculine and feminine traits. As with any pencil-and-paper personality indicator, it is good to remind students not to allow a number on a paper define who they are. Based on their BSRI scores, do students support or object to Tannen’s gender-based claims? It’s likely that those who are either highly masculine or feminine will be more likely to endorse her position than those in murky waters. A tricky test question You’ll notice that the second half of Essay Question #21 below is deliberately controversial and provocative. Students can choose the safe answer (Tannen’s official response)—that they are different, but equally valid. They can also opt for the integrative approach, arguing that since both styles are potentially useful it’s best to be as androgynous and flexible as possible. (Integrative Essay Question #30 below may be applicable here.) Or they can go out on a limb and explicate the inherent superiority of one approach or the other. To do so, they’ll have to establish appropriate criteria for judgment. Essay Question #25, which 452 takes an instrumental approach to the issue of differing styles, may provide some help in creating such criteria. Media and literary portrayals of genderlects Gender differences are an extremely popular theme for contemporary television shows and movies, and you’ll have no trouble finding recent clips that illustrate ostensible differences between the ways males and females communicate. In some ways, though, it might be more revealing to go back at least a decade or two, when writers and producers were less deliberate about portraying the ways in which men and women converse. Tannen is extremely adept at drawing upon literature to support her theory, so it may be interesting to present a literary example or two that complicates the picture. One possible candidate is Thorton Wilder’s classic play Our Town. Consider, for example, the long encounter in Act II when George and Emily communicate their true feelings for one another. George listens diligently and nondefensively to Emily’s rather harshly worded complaint about his character and focuses his response on relational—rather than hierarchical—issues. Because their rapport is of central importance to him, he confirms her perceptions and willingly discloses his private feelings to her. George, a sensitive young man of the early twentieth century, seeks to establish supportive, egalitarian, open communication about their relationship—there is no complementary schismogenesis here. Whereas the passage does not overturn every stereotypical expectation we have developed about communication between males and females, it suggests to students that individual differences and matters of personality are often the most salient aspects of communicative patterns. Perhaps George would have eventually turned out like his father, who avoids important relational communication with his wife by refusing to discuss a romantic vacation in Paris, but at this moment, at least, he seems to be a male at home with intimate connections and webs of relationships. Another excellent text is PBS’s The Farmer’s Wife. The evolution of Juanita and Darrel’s communication over the course of the film provides a profound case study for genderlect theory. When Em Griffin teaches this chapter, he shows his students the clip on male-female friendship from When Harry Met Sally (Cue Point: 0:08:50) featured in the chapter (471-72). He also recommends Tannen herself on video and encourages instructors to check out videos in which she is featured from their institutions’ libraries or media centers. He notes that the audiences for these video performances tend to be white and middle class, a point that could lead to some interesting discussion of the scope and range of her theoretical principles. In addition, Griffin likes to interrogate the “aha factor” Tannen claims validates her approach (478). To do this, he asks his students about their “aha” experiences, then discusses the extent to which these personal epiphanies are legitimately generalizable for the class. Is the “aha factor” really a valid way to conduct or test theory? 453 Further Resources § § § § § § § § § A good general collection of essays on related issues is Linda A.M. Perry, Lynn H. Turner, and Helen M. Sterk, eds., Constructing and Reconstructing Gender: The Links among Communication, Language, and Gender (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992). Particularly relevant is Nancy Hoar’s piece, “Genderlect, Powerlect, and Politeness,” 127-36. Annette Hannah and Tamar Murachver explore the genderlect hypothesis in “Gender and Conversational Style as Predictors of Conversational Behavior,” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 18 (June 1999): 153-74. Suzanne Braun Levine examines the importance of genderlects in the profession of journalism in “News-Speak and ‘Genderlect’—(It’s Only News if You Can Sell It),” Media Studies Journal 7 (Winter 1993): 114-23. William Rawlins’s Friendship Matters, which Griffin features in the Second Look section of Chapter 11, has much of interest to say about the ways males and females communicate with their friends and romantic partners. For a good example of the influence of Tannen’s work on the communication field, see Richard L. Weaver’s chapter, “Gender Communication: Understanding the Other Sex,” in Understanding Interpersonal Communication, 7th ed. (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1996), 245-70. Although Weaver includes the usual cautions about generalizations, his discussion—like Tannen’s—could be seen to perpetuate the very differences he seeks merely to describe, particularly his claim that “gender differences have as much to do with the biology of the brain as the way we are raised” (252). Heidi Reeder examines the assumptions, ideologies, and methodologies for studying gender differences in interpersonal communication in her article, “A Critical Look at Gender Difference in Communication Research,” Communication Studies 47, 4 (1996): 318-31. For a critical assessment of the male genderlect, see Peter F. Murphy, Studs, Tools, and the Family Jewels: Metaphors Men Live By (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001). For discussion of interruptions, see Sara Hayden, “Interruptions and the Construction of Reality,” in Differences that Make a Difference: Examining the Assumptions in Gender Research, eds. Lynn H. Turner and Helen M. Sterk (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1994), 99-106. Shawn Parry-Giles and Trevor Parry-Giles analyze problems with the “feminine style” of discourse in the political realm in “Gendered Politics and Presidential Image Construction: A Reassessment of the ‘Feminine Style,’” Communication Monographs 63 (December 1996): 337-53. 454 Other texts by Tannen § Framing and Discourse (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); and Gender and Conversational Interaction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993). § You may wish to check out her work, The Argument Culture: Stopping America’s War of Words (New York: Ballantine Books, 1999). Although probably misnamed—Tannen is not really against argument when it is conducted rationally, fairly, and productively—it takes on the discourse of contentiousness that may be too prevalent in our society. Two-cultures hypothesis in groups § Renee A. Myers, et al. provide empirical support for the dual cultures approach to malefemale communication in “Sex Differences and Group Argument: A Theoretical Framework and Empirical Investigation,” Communication Studies 48 (Spring 1997): 1941. § Katherine Hawkins and Christopher B. Power explore the presence of genderlects in small groups in “Gender Differences in Questions Asked During Small Decision-Making Group Discussions,” Small Group Research 30 (April 1999): 235-56. Critiques of Tannen § In The Mismeasure of Women (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), Carol Tavris offers an interesting critique of Tannen’s genderlects theory (297-301). For example, she argues, “What Tannen’s approach overlooks is that people’s ways of speaking . . . often depend more on the gender of the person they are speaking with than on their own intrinsic ‘conversation style’” (298-99). § Other critiques of the two-cultures approach to gender and communication can be found in Mary Crawford’s Talking Difference: On Gender and Language (London: Sage, 1995); and Elizabeth Aries’s Men and Women in Interaction: Reconsidering the Differences (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). § An attack on Tannen’s evidence for You Just Don’t Understand is launched by Daena J. Goldsmith and Patricia A. Fulfs in “‘You Just Don’t Have the Evidence’: An Analysis of Claims and Evidence in Deborah Tannen’s You Just Don’t Understand,” Communication Yearbook 22 (1999): 1-49. 455 Sample Examination Questions Sample Questions are not reproduced in the online version of the Instructor's Manual. To receive a copy of the Test Bank contact your local McGraw-Hill sales representative or email Leslie Oberhuber, Senior Marketing Manager at leslie_oberhuber@mcgraw-hill.com 456 Sample Questions are not reproduced in the online version of the Instructor's Manual. 457 Sample Questions are not reproduced in the online version of the Instructor's Manual. 458 Sample Questions are not reproduced in the online version of the Instructor's Manual. 459