Visualizing Social Studies Literacy

advertisement

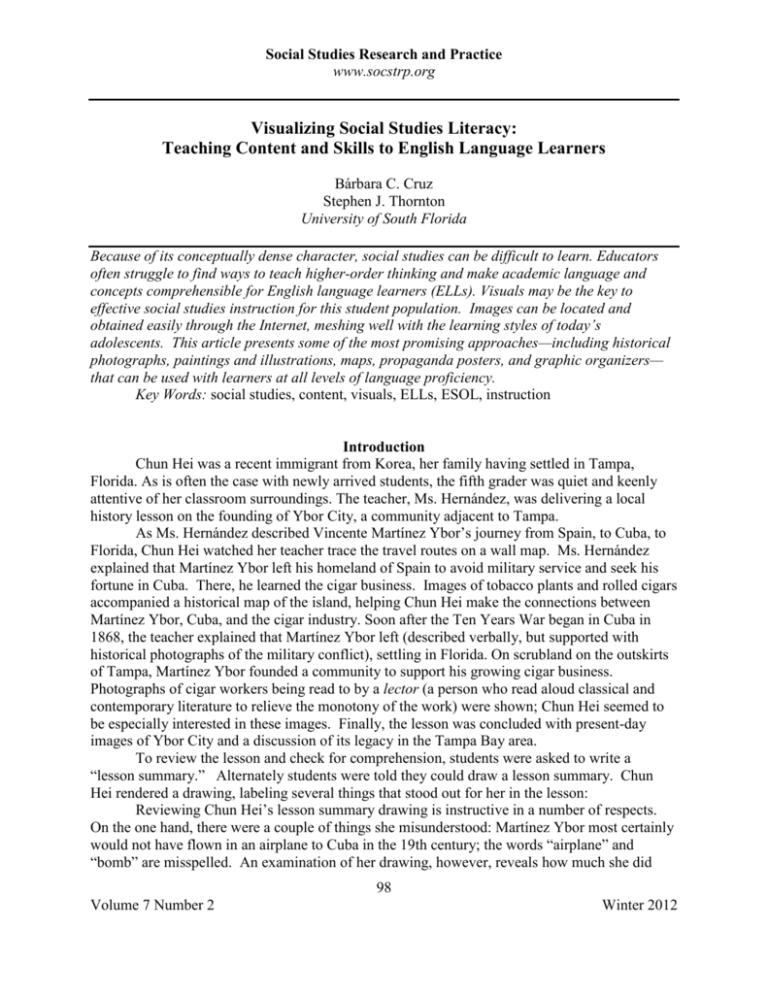

Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org Visualizing Social Studies Literacy: Teaching Content and Skills to English Language Learners Bárbara C. Cruz Stephen J. Thornton University of South Florida Because of its conceptually dense character, social studies can be difficult to learn. Educators often struggle to find ways to teach higher-order thinking and make academic language and concepts comprehensible for English language learners (ELLs). Visuals may be the key to effective social studies instruction for this student population. Images can be located and obtained easily through the Internet, meshing well with the learning styles of today’s adolescents. This article presents some of the most promising approaches—including historical photographs, paintings and illustrations, maps, propaganda posters, and graphic organizers— that can be used with learners at all levels of language proficiency. Key Words: social studies, content, visuals, ELLs, ESOL, instruction Introduction Chun Hei was a recent immigrant from Korea, her family having settled in Tampa, Florida. As is often the case with newly arrived students, the fifth grader was quiet and keenly attentive of her classroom surroundings. The teacher, Ms. Hernández, was delivering a local history lesson on the founding of Ybor City, a community adjacent to Tampa. As Ms. Hernández described Vincente Martínez Ybor’s journey from Spain, to Cuba, to Florida, Chun Hei watched her teacher trace the travel routes on a wall map. Ms. Hernández explained that Martínez Ybor left his homeland of Spain to avoid military service and seek his fortune in Cuba. There, he learned the cigar business. Images of tobacco plants and rolled cigars accompanied a historical map of the island, helping Chun Hei make the connections between Martínez Ybor, Cuba, and the cigar industry. Soon after the Ten Years War began in Cuba in 1868, the teacher explained that Martínez Ybor left (described verbally, but supported with historical photographs of the military conflict), settling in Florida. On scrubland on the outskirts of Tampa, Martínez Ybor founded a community to support his growing cigar business. Photographs of cigar workers being read to by a lector (a person who read aloud classical and contemporary literature to relieve the monotony of the work) were shown; Chun Hei seemed to be especially interested in these images. Finally, the lesson was concluded with present-day images of Ybor City and a discussion of its legacy in the Tampa Bay area. To review the lesson and check for comprehension, students were asked to write a “lesson summary.” Alternately students were told they could draw a lesson summary. Chun Hei rendered a drawing, labeling several things that stood out for her in the lesson: Reviewing Chun Hei’s lesson summary drawing is instructive in a number of respects. On the one hand, there were a couple of things she misunderstood: Martínez Ybor most certainly would not have flown in an airplane to Cuba in the 19th century; the words “airplane” and “bomb” are misspelled. An examination of her drawing, however, reveals how much she did 98 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org understand: the relative location of the places Martínez Ybor lived in; the war in Cuba; the movement of Martínez Ybor’s cigar business; the phenomenon of the lector in Ybor City. While the teacher’s explanation of the founding of Ybor City was effective enough, it was her use of visuals that seemed to make the content more accessible to Chun Hei as well as possibly other learners in the class. Allowing Chun Hei to represent her understanding in a visual format (and thus assessing her comprehension of the content) is the kind of true accommodation that English as a Second Language (ESOL) educators advocate (Pappamihiel & Mihai, 2006). In this article, we contend that visuals may be the key to effective social studies instruction for ELLs. While there is no universally accepted definition of what a “visual” is, for our purposes here, we mean photographs, drawings, paintings, and murals, maps, timelines, political cartoons, propaganda posters, realia, and charts and graphs. These can all be used to represent significant social studies content. All students benefit from this approach, but ELLs stand to benefit the most. Using Visuals in Social Studies Instruction Researchers have long underscored that worthwhile learning in social studies depends on it being taught for “understanding and higher-order applications” (Brophy, 1990). This has been a difficult objective to reach, and language barriers make it an even more ambitious objective for English language learners (ELLs). Both ESOL and subject-area educators often struggle to find ways to make language concepts comprehensible to ELLs. Social studies can be an especially difficult content area given its conceptually-dense content (Cruz & Thornton, 2010; Deussen et al., 2008). According to Judie Haynes (2009), of all the content areas, subject matters such as history, geography, and civics present the most formidable learning challenges for ELLs. One reason for this challenge is social studies’ high cognitive load, particularly its specialized jargon and low-frequency vocabulary terms (Szpara & Ahmad, 2006). Another factor is that the syntax of social studies textbooks is frequently complex: not only are there long sentences, there are also likely to be multiple dependent clauses and reliance on the passive voice (Brown, 2007). Primary sources are by definition from the past and often include formal or archaic language, which is an additional challenge for ELLs. Further factors generally make for even more difficulties in comprehension. In staple social studies courses such as U.S. history and government, for instance, knowledge of American culture is often presumed. But this may be the knowledge non-native students lack. Further, as a field dominated by typical instructional methods such as lecturing and textbook-based questioning, social studies offers very few scaffolds for ELLs learning. Although there are plenty of reasons why ELLs often flounder in it, social studies may also offer countervailing affordances for learning through visuals. Researchers have shown, for instance, that children as young as six can use historical photographs to compare past and present, put historical periods in sequence, and describe changes in terms of cause and effect (Barton, 2001). It may be that visuals hold potential for different types of students to engage in higher-order social studies thinking and learning (Cruz & Thornton, 2009). In the ESOL literature, visuals have long been promoted as effective tools of instruction (Bauer & Manyak, 2008; Bresser, Melanese, and Sphar, 2009; Chamot & Robbins, 2005; Echevarria, Vogt, & Short, 2007; Rivera et al., 2010). For one, they can be used to expand vocabulary, which is generally recognized as a key to developing academic literacy (Bisland, 99 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org 2010; Short & Fitzsimmons, 2007). As non-verbal forms of communication, visuals also can offer concrete representations of abstract concepts that are memorable for most students. Routinely, ESOL educators recommend programs along these lines for teaching subject-area content. Further, branches of social studies such as geography heavily rely on learning via visuals, which even a quick review of the items tested by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP, 2011) confirms. But in-depth exploration of how to design such programs rich in visuals has, at least until recently, been hard to come by. Hinde, Osborn Poppa, Jimenez-Silva, and Dorn (2011) provide a recent demonstration of how to utilize visuals in geography to develop elementary- and middlelevel ELLs’ reading and writing skills. Similarly, Colleen Klein Reutebuch (2010) illustrates how visuals and graphic organizers can play a central role in teaching social studies to middle grades ELLs. At the high school level, Michelle Sparza and Iftikhar Ahmad (2006) propose a multi-tiered approach that incorporates visuals to reduce cognitive load without reducing conceptual content. There is some empirical research on the use of visuals in ELL instruction (Deussen et al., 2008). Vaughn et al. (2009) report findings from two experimental studies showing that strategic use of videos and graphic organizers in social studies instruction contributed to the significant gains made by all students, including ELLs, in vocabulary and comprehension measures. Similarly, exceptional education researchers (Gersten et al., 2006) report that short video clips facilitate learning and foster active processing of content. In this study, students with and without learning disabilities scored significantly higher in measures of content comprehension. Thus far, we have suggested the literature, which might support the effective use of visuals for teaching higher-order thinking in social studies, is limited. Nonetheless, the studies point toward the efficacy of the approach. In the next section, we propose a range of methods for using visuals to teach higher-order thinking in social studies. Social Studies Visuals Using visuals fits with the learning styles of today’s adolescents. As Timothy Gangwer (2009) observes, they are “by far the most visually stimulated generation that our [educational] system has ever had to teach” (p. 1). Fortunately, the Internet has made locating and obtaining images for instruction easier than ever before. There are a number of reliable web sites that teachers can use to support instruction (see Web-Based References). While space limitations do not permit an exhaustive discussion here of every type of visual that can be used in a social studies classroom, this selective list is a good starting point. We offer here brief descriptions of some types of visuals that seem promising for teaching social studies to ELLs. Picture Dictionaries and Picture Books Picture dictionaries and picture books, which have long been staples of elementary classrooms, are often overlooked in secondary settings. Law and Eckes (2010) advocate providing student at all grade levels with picture dictionaries that have realistic pictures of everyday life, both in and out of school. In a civics unit, for example, images of a court room, city hall, or a voting precinct can be helpful in building vocabulary and can be used with students at all levels of language acquisition. Dong (2011) describes a cross-cultural proverb picture dictionary in which secondary ELLs work collaboratively to visualize words while facilitating 100 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org language and cultural appreciation. A study by Fry and Gosky (2007) points to the promise of electronic pop-up dictionaries, that is, on-line texts on which students can click to obtain pronunciations, definitions, and pictures. The experimental group of middle school students in the study earned higher reading comprehension test scores than students who used regular texts or online texts without the dictionary. Figure 1 A lesson summary on Ybor City, Florida Although picture books are generally abandoned in the upper elementary grades in favor of chapter books and standard textbooks, this seems an overreaction. Age-appropriate picture books in the secondary classroom can provide a portrait of a social setting and, at the same time, make the content accessible for students (see, for example, Billman, 2002; Carr et al., 2001). Wilkins and colleagues (2008) show how civil rights picture books can be used in the secondary classroom to tackle difficult issues of racism and discrimination in historical context. Used as an introduction to a topic, a deeper exploration of an event or historical figure, or as a concluding activity that brings closure to a lesson, picture books can provide visual interest for all students in the social studies classroom. Historical photographs Historical photographs serve as compelling records of people, places, and events and present rich learning opportunities (Levstik & Barton, 2008). They are “tangible historical evidence” (Library of Congress, 2010). Photographs can be used as an advanced organizer or as a pre-reading tool to generate interest or to accompany teacher explanations. In any case, photographs provide illustrative representation of the aural content. Photographs can help develop analytical skills. Students, for example, can be asked to consider who made the image and for what purpose. As Jenny Wei (2009) points out, photographs can serve as significant springboards for discussion. Furthermore, use of historical photographs is an authentic activity as students can construct their own accounts of a time in the past (Barton, 2001). 101 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org Consider this image taken in Oklahoma in 1936. The term “dust bowl” is a difficult one to grasp for a variety of reasons. A teacher can provide meaningful visual support to a lesson on the Dust Bowl by using such a photograph. The image can be used to introduce a lesson, to stimulate curiosity, at the end to sum up, or at some other instructional opportunity. Viewing an image such as this one can give a very clear idea of what it entailed. Students can be asked: How many people do you see? What are they doing? Why do you think they are running? Describe the landscape. Are there plants growing there? What is the sky like? Why does the house seem so low? Depending on their level of language development, students can point to items in the picture, can use simple adjectives to describe what they see, or can form short sentences to tell what they think about the image. Figure 2 Source: Library of Congress, Cimarron County, Oklahoma. 1936. Photographer: Arthur Rothstein Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsc-00241 Paintings and Illustrations Paintings and illustrations, especially if they were produced in the time period under study in a history class, can provide valuable source material about the era. Paintings can serve double-duty. First, an individual painting can give an impression of what some feature of the past 102 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org may have looked like. Since few students are likely to know what a medieval feast or San Francisco during the gold rush looked like, this type of learning is valuable for students. But, paintings are also valuable in another way. Students can grapple with interpreting a painting: Is its mood dark or bright? Why did the artist paint this scene? Of course, many of these questions can probably not be definitively answered, but closure should not be the objective. The exercise in interpretation is itself an authentic task of historical reasoning. In addition to single paintings or illustrations, more than one image can invite comparison of perspective on an event, a person, or a series of paintings showing clearly different eras. This can be good way to teach chronology. As an example, students can grapple with the important changes in art when presented with one painting that represents pre-Renaissance art (e.g., Madonna and Child by Duccio di Buoninsegna) and a second painting that was created during the Renaissance (e.g., Jan van Eyck's Arnolfini Marriage). By careful examination and comparison, students will deduce the main differences between pre-Renaissance and Renaissance art, namely: Pre-Renaissance art explored mostly religious themes, made use of flat features, and featured the extensive use of gold paint, while Renaissance artists employed three dimensional techniques, linear perspective, shadowing, lighting, realism, naturalism, and nonreligious content. Political Cartoons Political cartoons are accepted forms of social commentary. They generally use humor or sarcasm to persuade a reader to consider a particular point of view. For students who have lived in autocratic countries, the notion of political cartoons may be new. The role of citizens, the limits of government power, and the definition of citizenship are concepts that can be explored with political cartoons. Figure 3 Source: Library of Congress. 1754 political cartoon by Benjamin Franklin which appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette 103 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org Benjamin Franklin created one of the most famous political cartoons in 1754. The cartoon appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette during the French and Indian War and showed a snake divided into pieces. After an introductory lesson on the coming of the American Revolution, students can be guided through an analysis of the cartoon by asking: Describe the image. What do the initials and the pieces represent? What do you think Franklin was trying to say? Students also can look for political cartoons in the daily newspaper as well as online. The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (http://nieonline.com/aaec/cftc.cfm) provides background on cartoons, lesson plans, and worksheets for students. Maps Maps provide visual representations of regions on Earth. They are valuable tools and sources in geography, history, and cultural studies. Maps are marvelously adaptable to a host of instructional needs. They can be extremely simple. As a rule, maps should be adapted to the theme of a lesson. Extraneous information should not be allowed to clutter the map, especially with ELLs. As with paintings, maps can be useful for their conveying of information. It is much easier to show by a map Lewis and Clark’s route from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean than tell it in words. Yet maps, like paintings, can also be studied for their historical or cultural meanings (Monmonier, 1996; Segall, 2004). What a mapmaker thinks is worth including on a map is itself a valuable social studies learning activity. Alternately, students might examine an atlas and hypothesize about the use of different scales for different regions of earth and the social implications thereof. Propaganda Posters Figure 4 104 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org Propaganda posters are created, often during times of crisis, to persuade people something should be supported. They often beseech the viewer to take action. They employ powerful images designed to elicit an emotional response. Because text is limited, only the most important words are included. In a social studies class, vocabulary can then be taught in context. The study of both World War I and World War II offer opportunities to examine propaganda posters. Propaganda posters were used in both wars to persuade people to support U.S. involvement. Consider, for example, this propaganda poster made in the U.S. in 1917. Students can be asked: Who is the man in the poster? What is he doing? Who is he talking to? What is the main message of the poster? Similarly, students can view one of the best-known posters from World War II. Students can be told that during World War II, propaganda tried to influence women to work in war industries. After looking at the poster for a few minutes, students can be asked: Describe the woman in the poster. What is she wearing? Does the woman look strong or weak? What is the woman saying? What does that mean? Do you think this poster made more women want to work outside the home? Both of these propaganda posters are iconic images that students are likely to encounter even in present-day materials. They not only teach social studies content and develop analytical skills, but they also serve as important cultural literacy exemplars. Figure 5 We Can Do It! poster by J. Howard Miller depicting "Rosie the Riveter." 105 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org Charts and Graphs T-charts, line and bar graphs, and pie charts are used extensively in the social studies. By presenting data visually, ELLs can more easily understand and interpret information. As an example, if data are presented in only words or numbers, students have to carefully read the text to extract meaning. If these same data, however, are presented in the form of a pie chart or bar graph, students can easily compare the size of the pie edges or the bar heights. Consider, for example, this double bar graph of U.S. Civil War casualties. After an introductory lesson on the U.S. Civil War, students could be instructed to look up the definitions of “wounded,” “wounds,” and “disease.” Students could then answer: Which side had more deaths due to wounds? Did more soldiers die of wounds or disease? Overall, which side suffered more deaths? In addition to the many charts and graphs that can be found on the web, many word processing programs allow the user to create these visual representations easily and quickly by inputting raw data. Figure 6 Source: U.S. Dept of Veterans Affairs Realia Figure 7 Harappa board game from Indus Valley, Harappa Museum 106 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org Showing real objects can teach vocabulary, illustrate a concept, or provide a concrete referent for an abstract construct. Real-life objects and materials can also be used as part of a teacher demonstration; science teachers have used objects in this way for many years. While it is more powerful to bring in actual objects into the classroom (and, preferably, to allow students to handle them), showing images of archaeological artifacts can also bring the immediacy of realia into the social studies class. For example, this object was found in the Indus Valley. Students can be told that some of what we know about early societies comes from artifacts that have been found deep in the earth. By analyzing archaeological evidence, we can learn about what early societies were like. After viewing the object for a few minutes, students can be asked: Describe the artifact. What do you think it is? What does this object tell you about the people who created it? Timelines Timelines help students understand the chronological order of events. They also can show how much time passed between events, how things change over time, and cause and effect relationships. Timelines can be used as pre-teaching activities, during instruction, or as a summary tool. Especially helpful are timelines that have pictures embedded in them. Hines (2006) points out that timelines can provide comprehension support for ELLs by helping them make connections between events as they keep track of events in chronological order. A timeline such as this one can help students understand the events leading up to the American Revolution: 1754-1763: England fights in the French and Indian War; England goes into debt 1764: To pay off its war debt, England begins passing laws requiring colonists to pay new taxes 1773: Colonists protest the tax on tea 1775: The American Revolution begins 1776: Colonists write the Declaration of Independence It should be noted that many ELLs may be from cultures where year-by-year chronologies are not common; they may be more familiar with timelines that reflect dynasties, eras, or period of times clustered in other ways. Graphic Organizers Graphic organizers arrange and present content visually. They organize text and concepts in a way that is comprehensible and hence more easily understood. Extraneous text is omitted and only the most essential information is included. This makes the content much more manageable for ELLs. Like timelines, graphic organizers can be used as pre-teaching activities, during instruction, or as summary and assessment tools. When used as advance organizers, they can focus students’ attention on the most important aspects of the lesson and can reduce anxiety by letting students know what they should take notes on (Walqui, 2008). Venn diagrams help students see relationships between and among groups. This Venn diagram, for example, compares and contrasts the Mayan and Aztec civilizations. The information in the Venn diagram can be taken from the textbook, presented by the teacher, or gleaned through student research. Students can be asked to name something in the Mayan 107 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org civilization that was not in the Aztec civilization, name something that was only true of the Aztec civilization, and to list what both civilizations had in common. Figure 8 Venn Diagram (reprinted, with permission, from: Cruz, B.C & Thornton, S.J. Gateway to Social Studies. Boston, MA: National Geographic/Cengage Learning, 2013.) built great cities, pyramids, palaces; developed accurate calendar; knowledgeable about astronomy, Conclusions Visuals can greatly reduce cognitive load in learning while simultaneously exposing students to conceptually rich subject matter. Thus, ELLs, struggling readers, exceptional education students and other student populations can grapple with the substantive ideas social studies is designed to impart. All too frequently, ELLs work with materials whose chief educational virtue is their simple English, but lacking in the conceptual complexity that is the point of the exercise. Already there seems more than ample reason to recommend the approach to instruction we have outlined. Nevertheless, the methods we propose are ripe for experimentation specific to ELLs in social studies teaching, research, curriculum design, and teacher education. 108 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org References Barton, K.C. (2001). A picture’s worth: Analyzing historical photographs in the elementary grades. Social Education, 65(5), 278-283. Bauer, E.B. & Manyak, P.C. (2008). English learners: Creating language-rich instruction for English-language learners. The Reading Teacher, 62(2), 176-178. Billman, L.W. (2002). Aren’t these books for little kids? Educational Leadership, 60(3), 48-51. Bisland, B. M. (2010). Another way of knowing: Visualizing the ancient silk routes. The Social Studies, 101(2), 80-86. Bresser, R., Melanese, K., & Sphar, C. (2009). Equity for language learners. Teaching Children Mathematics, 16(3), 170-177. Brophy, J. (1990). Teaching social studies for understanding and higher-order applications. The Elementary School Journal, 90(4), 352-417. Brown, C.L. (2007). Strategies for making social studies texts more comprehensible for English language learners. The Social Studies, 98(5), 185‐188. Carr, K.S., Buchanan, D.L., Wentz, J.B., Weiss, M.L. & Brant, K.J. (2001). Not just for the primary grades: A bibliography of picture books for secondary content teachers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45(2), 146-153. Cruz, B.C. & Thornton, S.J. (2009). Teaching social studies to English language learners. New York: Routledge. Deussen, T., Autio, E., Miller, B., Lockwood, A.T., & Stewart, V. (2008). What teachers should know about instruction for English language learners. Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. Dong, Y.R. (2011). Unlocking the power of academic vocabulary with secondary English language learners. Gainesville, FL: Maupin House Publishing. Gersten, R., Baker, S.K., Smith-Johnson, J., Dimino, J. & Peterson, A. (2006). Eyes on the prize: Teaching complex historical content to middle school students with learning disabilities. Exceptional Children, 72(3), 264-280. Echevarria, J., Vogt, M. & Short, D. (2007). Making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP model (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon. Francis, D.J. & Vaughn, S. (2009). Effective practices for English language learners in the middle grades: Introduction to the special issue of Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 2(4), 289-296. Gangwer, T. (2009). Visual impact, visual learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Hinde, E.R., Osborn Poppa, S.E., Jimenez-Silva, M., & Dorn, R. (2011). Linking geography to reading and English language learners’ achievement in US elementary and middle school classrooms. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 20(1), 47-63. Law, B., & Eckes, M. (2010). The more-than-just-surviving handbook: ELL for every classroom teacher. Canada: Portage & Main Press. Levstik, L. S., & Barton, K.C. (2008). Researching history education. New York: Routledge. 109 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org Monmonier, M. (1996). How to lie with maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. Pappamihiel, N. E. & Mihai, F. (2006). Assessing English language learners' content knowledge in middle school classrooms. Middle School Journal, 38(1), 34-43. Reutebuch, C. K. (2010). Effective social studies instruction to promote knowledge acquisition and vocabulary learning of English language learners in the middle grades. Houston, TX: The National Center for Research on the Educational Achievement and Teaching of English Language Learners. Rivera, M. O., Francis, D. J., Fernandez, M., Moughamian, A., C., Lesaux, N. K., & Jergensen, J. (2010). Effective practices for English language learners: Principals from five states speak. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction. Segall, A. (2004). Maps as stories about the world. Social Studies and the Young Learner, 16(1), 21-25. Short, D.J., & Fitzsimmons, S. (2007). Double the work: Challenges and solutions to acquiring language and academic literacy for adolescent English language learners. New York: Alliance for Excellent Education. Szpara, M.Y. & Ahmad, I. (2007). Supporting English-language learners in social studies class: Results from a study of high school teachers. The Social Studies, 98(5), 189-196. U. S. Department of Education. (2011). The nation’s report card: Geography 2010. Washington, DC: Author. Vaughn, S., Martinez, L., Reutebuch, C., Linan-Thompson, S., Carlson, C., & Francis, D. (2009). Enhancing social studies vocabulary and comprehension for seventh-grade ELLS: Findings from two experimental studies. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 2, 297-324. Walqui, A. (2008). The development of teacher expertise to work with adolescent English learners: A model and a few priorities. In Verplaetse, L.S. and Migliacci, N. (eds). Inclusive pedagogy for English language learners (pp. 103-125). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Wilkins, K.H., Sheffield, C.C., Ford, M.B., & Cruz, B.C. (2008). Images of struggle and triumph: Using picture books to teach about civil rights in the secondary classroom. Social Education, 72(3), 177–180. Web-Based References Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. (n.d.) Cartoons for the classroom. Retrieved from http://nieonline.com/aaec/cftc.cfm Chamot , A.U., & Robbins, J. (2005). The CALLA model: Strategies for ELL student success. Retrieved from http://calla.ws/CALLAHandout.pdf Cruz, B.C., & Thornton, S.J. (2010). Using visuals to build interest and understanding. Retrieved from http://teachinghistory.org/teaching-materials/englishlanguage-learners/24143 Enchanted Learning. (n.d.). Curriculum Materials Online. Retrieved from http://www.enchantedlearning.com/Home.html 110 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012 Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org EverythingESL.net. (2011). Graphic Organizers. Retrieved from http://everythingesl.net/inservices/graphic_organizers.php Haynes, J. (2009). Challenges for ELLs in content area learning. Retrieved from http://www.everythingesl.net/inservices/challenges_ells_content_area_l_65322.php Hines, A. (2006). Using timelines to enhance comprehension. Retrieved from http://www.readingrockets.org/article/13033 Library of Congress. (2011). Photographs and Prints. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/pictures Library of Congress. (2010). Supporting English language learners. Teaching with Primary Sources Quarterly. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/teachers/tps/quarterly National Geographic. (2012). National Geographic Education. Retrieved from http://education.nationalgeographic.com/education Sparza, M. Y., & Ahmad, I. (2006). Making social studies meaningful for ELL students: Content and pedagogy in mainstream secondary school classrooms. Essays in Education 16, http://www.usca.edu/essays/vol162006/ahmad.pdf Wei, J. (2009). Using objects with English language learners. National Museum of American History. Retrieved from http://blog.americanhistory.si.edu/osaycanyousee/2009/10/using-objects-with-englishlanguage-learners.html Author Bios Bárbara C. Cruz is Professor of Social Science Education at the University of South Florida. Her research and teaching interests include global and multicultural perspectives in education and diversity issues in teacher preparation. She wrote, with Stephen J. Thornton, Teaching Social Studies to English Language Learners (Routledge, 2008). E-mail: bcruz@usf.edu Stephen J. Thornton is professor of Social Science Education at the University of South Florida. His teaching and research interests include integrating geography in the teaching of American history. He wrote, with Bárbara C. Cruz, Gateway to Social Studies, which introduces middle-grades English language learners to geography, history, and civics. 111 Volume 7 Number 2 Winter 2012