Political, Cultural and Both: Swiss Diverging Visions on

Political, Cultural and Both: Swiss Diverging Visions on National Identity

Paper to be presented at the annual conference of the Swiss Political Science

Association. Geneva, January 7-8, 2010.

Beatrice Eugster

Institute of Political Science

University of St.Gallen

Bodanstrasse 8

CH-9000 St.Gallen beatrice.eugster@unisg.ch

Oliver Strijbis 1

Institute of Political Science

University of St.Gallen

Bodanstrasse 8

CH-9000 St.Gallen oliver.strijbis@unisg.ch

1 Oliver Strijbis’ research is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation through the “National Centre for Competence in Research – Challenges to Democracy in the 21st Century”.

Abstract

The aim of our analysis of Swiss national identity is twofold. First, we test whether

Switzerland really is a prototype of a political nation or whether cultural forms of national identity are prominent too. Second, we challenge the (implicit) statement made in cross-country comparisons that citizens identify with a similar content of national identity. Instead, we claim that different images of Swiss nationhood are related to an individual’s party affiliation. To test our propositions we conduct factor and regression analysis on data from the Swiss Eurobarometer 2003. Our results show that Switzerland is divided into those imagining the nation in cultural terms and those who do not. They also confirm that party affiliation helps to explain the divide even if its effect is minor.

2

Introduction

Switzerland is widely perceived as a prototype of a political nation. The Swiss identity, so the claim, is based upon a common appreciation of political values such as direct democracy, neutrality and federalism. Simultaneously it has been shown that in the same country the main dimension of political conflict in recent years has been about

“cultural demarcation” (Kriesi et al. 2008). How is it possible that in a country that perceives itself as a nation of will (‘Willensnation’), the most important political fights are about whether it should be culturally open or not? This paper tries to solve this puzzle by maintaining that the tale of the Swiss ‘Willensnation’ falls short. It neglects the fact, so our argument, that Switzerland is divided between those who imagine the

Swiss to be a cultural nation and those who do not.

The question whether Switzerland is a political nation, a cultural one or both has important consequences for ongoing debates about the perspectives of a potential

European nation and for the prospect of the national identity in immigrant societies. At the centre of this debate stands the question whether a ‘constitutional patriotism’ (e.g.

Habermas 1990) is sufficient for state integrity and national solidarity or whether a common cultural identity is needed (e.g. Huntington 2004). In this debate, Switzerland is a crucial case because the Swiss nation is often cited as an example of a political nation that is solidary and does not show tendencies to disintegrate.

One part of the existing empirical literature focuses on the emergence of Swiss national identity and especially emphasizes the role of the elite and intellectuals by using historical analysis (Kohn 1956; Deutsch 1976; Froidevaux 1997; Stojanovic 2003;

Kriesi et al. 2008). Thereby the creation of national symbols, as for example the importance of the alpine region and its peasant community, is highlighted (Zimmer

1998; Berthoud 2001). Although some studies analyze the influence of historical experiences on recent developments in policy making (cf. Sciarini et al. 2001) or how the political elite represents Switzerland abroad (Müller 2008), they are often built on the general assumption that the nation is based on the shared identity of its members.

Another strand of the literature on Swiss identity examines the relationship between national identity and the masses. To account for other economic and social groups than the elite, some authors analyze specific forms of political rituals at the societal level and

3

show how their meaning has changed over time.

2 The institutions studied are, for example, national exhibitions (Torriani 2002), museums and monuments (Santschi

1991) and the role of national literature in schoolbooks (Helbling 1994, Rutschman

1994). Only few, however, were able to make generalizations for the entire Swiss society by using representative surveys. These have focused on the influence of the current national identity on national elections and attitudes toward the European Union

(Kriesi 2002; Christin and Trechsel 2002).

While previous studies have focused either on the cultural (cf., Mottier 2000) or the political dimension (cf. Kriesi and Trechsel 2008) of national identity, we focus on the mutual relation of these two types within the Swiss nation. By looking at different contents of national identities within the same nation we draw on recent contributions in political sociology arguing that differences between nations have been overvalued, while differences within them have been underestimated. By trying to explain differences in the images of national identity among the citizens, we go even one step further. In order to do so we draw on literature which emphasizes that the content of

Swiss national identity is highly political. This leads us to the hypothesis that party affiliations matter for imaginations about the content of the national identity.

Our main finding is that Switzerland reached a national consensus about what constitutes the political identity of the nation, but that the country is divided concerning its cultural identity. While one camp imagines the Swiss nation as a purely political community, the other camp perceives the Swiss as a people also united by a common culture. We furthermore find some evidence that party affiliation partly predicts whether people imagine the Swiss nation as a purely political or a political and cultural nation.

The paper is structured in two main chapters. In the first chapter we investigate the content of the Swiss national identity. First, we defend our assumption that the Swiss can be considered one nation. Thereafter we provide empirical evidence that the Swiss national identity consists of two main dimensions, a cultural and a political one. We do so by analyzing survey data. In the second chapter, we try to explain the variance concerning the cultural dimension of the Swiss identity. We propose that party

2

Bendix (1992), for example, compares the discourse of political rituals of the marksmen’s festival in

1849 with the creation of the national holiday in 1899 and the 650 th

anniversary of the Swiss

Confederation in 1941. She finds that these rituals can enact national sentiment even if it does not last long.

4

affiliation might explain whether citizens perceive the Swiss nation to contain a cultural dimension or not. We empirically test our hypothesis with regression analysis.

The divide within: Two images of national identity in Switzerland

Debates about countries being national or multinational, and minorities being ethnic or national have sometimes resulted in debates on (implicit) definitions rather than on substantial issues. As a consequence thereof many political scientists have simply resigned to make explicit their understanding of ‘nation’ and ‘national identity’

(Greenfeld 1999, 45). For the sake of clarity, we will nevertheless make explicit our use of these ‘essentially contested’ concepts. A nation , for instance, is understood as a group of people which perceives itself as ‘naturally’ belonging to a certain state

(Brubaker 1999). This means that a nation is an ‘imagined community’ (Anderson

1983) because it depends on subjective self-identification and – in contrast to other

‘imagined communities’ – imagines its community as being related to a state (e.g.

Miller 1995).

3 Hereby it does not matter whether this state actually exists or constitutes the goal this community strives for. National identity points to the salience of this identity and the content thereof. While the salience of the identity points to the degree to which citizens identify with the nation, the content of the identity refers to the quality of this imagination.

4

One nation…

Whether Switzerland constitutes a mono-national or multi–national state is highly debated. This question is important because it determines how many national identities exist within a state.

3 We prefer such a definition to substantial ones because it takes the possibility that a group has a national identity without being culturally united into account. We further do not include here the often–mentioned condition that someone belongs only to a certain nation if this is accepted by ‘the others’ (e.g. Gellner

1983, 3) .

4 Former question relates to a psychological understanding of nationalism. It is sometimes distinguished from patriotism, which stands in contrast to nationalism understood as an identification that allows for a critically reflected account of its own nation. It is further distinct from a sociological understanding of nationalism, which understands it as an ideology claiming that the state and the nation should be congruent (e.g. Gellner 1983, 3).

5

Arguments for Switzerland being a multi-national state can be traced back to the 19 th century when the importance of cultural features as defining characteristics of a nation emerged. Intellectuals underlined the lack of ethnic unity in Switzerland and claimed that the Swiss nation was no more than a mere invention of German authors (Kohn

1956). Since then the idea of the Swiss nation as a multinational state has been maintained (cf. Deutsch 1976, 63; Abizadeh 2002; Bhattacharyya 2007). Kymlicka

(1995, 18), for example, labels Switzerland the ‘most multinational country’ because the different language regions do not share the same language and therefore the same culture.

5 The classification of Switzerland as a multinational state is, however, often based on the assumption that a common language constitutes the basis of a nation.

Multi-lingual is equated with multi-national (Dardanelli forthcoming).

6 Some authors emphasize that language is more than a cultural element which holds an ethnic homogeneous group together. They claim that a common language is central for a constitutional democracy because it facilitates the communication among citizens in the political process (Ipperciel 2007). Switzerland, then, is defined as ‘multinational’ not by the simple fact that it is multilingual, but because the different linguistic groups do not share a common public space.

7 In Switzerland, this ethno-linguistic division is further enhanced by the practice of federalism in mass media and education (Erk 2003).

Against the claim of Switzerland being a multi-national country, some authors defend the notion that the Swiss case represents a ‘true nation-state’ (cf. Hobbesbawm 1992,

65; Renan 1889, 893; Mill 1977, 546; McRoberts 2001). Stojanovic (2003) demonstrates that the Swiss nation was politically constructed in the period between the creation of the Helvetic Republic in 1789 and the establishment of the federal state in

1848. In the 19 th century the Swiss elites and intellectuals reacted against ‘cultural’ criticism raised abroad. As the main Swiss national characteristics they accentuated the

‘love of freedom’ and the attachment to the territory, mainly the Alps, instead of

5 Kymlicka (1995, 11) defines a nation as ‘a historical community, more or less institutionally complete, occupying a given territory or homeland, sharing a distinct language and culture’ and uses this term as synonymous with culture.

6

Also Kriesi (1999, 18) argues that the Swiss nation is a ‘federation of nations’.

7 As he correctly emphasis language is not a sufficient condition to classify a case as a multinational state

(Ipperciel 2007, 41).

6

ancestors and patriotic sagas.

8 These symbols helped to form the idea of one Swiss nation despite language divisions (Kriesi & Trechsel 2008). Evidence from surveys has repeatedly shown that in recent times the Swiss linguistic communities neither perceive themselves as distinct ‘nations’ nor identify themselves primary with their linguistic groups, but identify with Switzerland in general (cf. Kriesi et al. 1996, Stojanovic

2003). The survey data used here confirms this evidence. Table 1 shows that the large majority of the population, 45.9%, is strongly attached to the Swiss nation. This attachment does not vary largely across language groups. The difference is only 3.4% between French and German speakers and 6.3% between Italian and German speakers.

In all language groups the share of respondents that feel at least close to Switzerland is over 85%.

Table 1 about here

This result confirms our assumption that there is only one Swiss national identity shared by all citizens and is compatible with our definition of a nation as a group, which imagines itself as congruent to a state. A ‘mono-national Switzerland’, however, does not suffice to conclude that all Swiss share the same content of national identity.

…two identities

As the relation between state and nation is not imagined as accidental, it is related to some characteristics which make it possible to distinguish a particular nation from other nations. These characteristics must not be objective markers like language, denomination, but can be purely subjective (common will, values, beliefs etc.).

9

Furthermore it does not matter whether and how the imaginations are related to reality.

They can be based upon ‘invented traditions’ (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1992), ‘myths of common descent’ (Smith 1986) and the like. They do, however, need to contain an

8 These political and intellectual ideas were then taken up in the consciousness of the population through several practices – as institutionalization of a national holiday, marksmen's festivals and national exhibitions – and helped to create a collective national identity (Stojanovic 2003).

9

According to our definition and in contrast to ethnic groups, nations do not need to share a belief in common descent. A definition insisting on the ‘ethnic core’ of nations is counter-intuitive as it rules out the possibility that communities like the Americans form one nation.

7

image of the content of national identity which makes this particular nation unique and justifies its right upon an “own” state.

There is a long tradition in political science to categorize the content of these national identities into different types (Brubaker 1999).

10 In particular the distinctions between political and cultural as well as civic and ethnic have remained widely used until today

(Nieguth 1999). In the civic-ethnic distinction the ‘civic’ category includes political and inclusive cultural values, the ‘ethnic’ category refers to a narrow understanding of ethnicity essentially meaning perceptions of common descent.

11 In the political-cultural distinction, in contrast, the ‘political’ category is more narrow while the ‘cultural’ refers to a set of features that includes inclusive and exclusive cultural concepts. If the two dichotomies are combined, three types of national identity can be distinguished: a political, an inclusive-cultural and an exclusive-cultural identity (see also Nieguth

1999).

A political national identity refers to ‘constitutional patriotism’. It means that people imagine the nation as a community sharing the same political values. They can refer to the political system of a country, its political culture or its role in the world. The inclusive cultural identity refers to cultural characteristics which are not perceived as inherited but as acquirable. These are, for instance, common values such as a Protestant work ethic, sincerity, generosity, hospitality as well as lifestyles, language and religion.

Although such an identity asks a lot of those who want to assimilate to it, it does not make it impossible by definition. This is different with the exclusive cultural identity .

An exclusive cultural identity imagines the nation as a group of people sharing cultural markers that are inherited and can therefore not be acquired. These categories imply in particular ethnicity and race. Although it is true that ethnicity and race are socially constructed categories and might therefore be modifiable, individuals which do not belong to the ethnic or racial community cannot assimilate to it by themselves. It is only possible if the society at large redefines the boundaries of these ethnic and racial categories.

12 But because perceptions of ethnic and racial categories are socialized over generations they remain relatively stable over time.

10 Apart from typologies that refer to the content of the identity several have referred to its historical formation.

11

The civic-ethnic and political-cultural distinctions only differ if the civic category is understood broadly and the ethnic narrowly as we propose here. On definitions of ethnicity see Chandra (2006).

12 For example the category ‘white’ shifting to a meaning that includes the category of ‘latino’.

8

Whether one of the two classic dichotomies or the threefold typology really helps to categorize national identities is an empirical question. Classical notions of Swiss identity claim it to be political, based on a common appreciation of neutrality, federalism and direct democracy (Kriesi and Trechsel 2008, 11). According to this view it is the attachment to these fundamental political principles and institutions that unites the Swiss citizens and therefore builds the core of Swiss national identity. This overly rational conception of ‘constitutional patriotism’ (Habermas 1990) or purely political national identity, however, does, according to some, not suffice to the demands of emotional attachment (e.g. Huntington 2004).

13 Kriesi (2007a) therefore argues that the political national identity at the federal level is complemented with an ethnic conception of national identity at the cantonal and communal level. Others maintain that the national identity must not necessarily contain a cultural dimension, as invented myths about glorious ancestors can be combined with this mere rational political national identity. Besides invented myths, also rituals, traditions and national symbols can be considered forms of transmitting the image of national identity. From this point of view, the alpine landscape, for example, can be related to certain historical events or myths and seen as a symbol of the ancient military success against foreign invasions or as a place where the founders of the confederation came together to confirm their alliance.

In this frame, the Alps are associated with the tradition of direct democracy and therefore convey a political meaning.

As we want to emphasize, myths, rituals and national symbols can, however, not be a priori classified as political or cultural.

14 The Alps, for instance, can also be related to the place of descent of the ‘homo alpinus helveticus’, the true ancestor of the Swiss race

(cf. Mottier 2000, Kreis 1989). From this perspective, the Swiss mountain landscape does not refer to a political conception of national identity but clearly an ethnic one.

Hence Switzerland is also considered as a cultural nation because the ethnic component of Swiss identity constitutes an element of the national identity (cf. Kreis 1989). These ethnic components can be found in eugenic discourses about gender, sexuality and race,

13 Renan (1889, 307) highlights two points: the memory of a common past and the present accord to conserve this heritage.

14

This contrasts with Kriesi (2007b) who classifies national symbols as elements of the political culture and Froidevaux (1997) stating that they are part of an ethnic conception of national identity that contrasts to the civic conception of a common political culture based on federalism and the instruments of direct democracy.

9

which played a central role to build the national identity at the end of the 19 th century

(Mottier 2000, 2008). Finally, the Alps and especially the alpine community can also reflect common Swiss values as diligence, humility and order. In schoolbooks, for example, values were transmitted through references to the alpine landscape and their inhabitants (Helbling 1994). Here, the Alps and the associated values are connoted in a cultural inclusive sense that can be adopted by everyone even without having the same decent.

Despite emphasizing different elements of the national identity, these studies share an approach that categorizes the national identity as a whole. This reflects the practice in comparative politics where typologies of nationalism are applied to country comparisons. Although they have shown some variance in types of identities across nations, they have tended to underestimate similarities between countries. The civic vs. ethnic divide between West and East, for example, is only partly comparable and does not adequately describe what is in reality a more complex picture (Shulman 2002). The underestimation of similarities between countries is due to an undervaluation of variance within countries. Just as the categorization of entire countries underestimates the similarity between countries, it overestimates the degree of consensus within the nation about the content of its identity (Jones and Smith 2001; Heath and Tilley 2005).

Interestingly, individuals of the same nation need not share the same image of what the common characteristics of the nation are.

To test our hypothesis that Switzerland has a political as well as a cultural component of national identity, we use the data collected in the Swiss Eurobarometer 2003. We only select respondents that are Swiss citizens to assess the Swiss national identity. The dataset contains several questions about what makes a ‘true Swiss’. We also included questions to account for the specific characteristics of the Swiss political identity.

15

Table 2 gives an overview of how the answers of the respondents are distributed according to the different questions.

Table 2 about here

15 Persons that selected the option ‘Can’t choose’, about 9% of the respondents, were removed from the analysis to avoid biased results.

10

In general, the respondents tend to score rather high on all questions with the exception of the questions about religion and Swiss ancestry. Direct democracy is the most important of the three political institutions, about two thirds of the respondents stated that direct democracy is ‘very important’. The share of persons that think that neutrality or federalism is ‘very important’ is smaller with 43.9% and 29.3% respectively. About

80% of the respondents, however, indicated that each of these institutions is at least fairly important.

16 The items ‘respect of institutions’ as well as ‘speak a national language’ and ‘have a Swiss citizenship’ are highly valued across the respondents as part of national identity. More than 96% and 93% of the respondents, 81% respectively, stress their importance. The ‘feeling to be Swiss’ and the ‘time spent in Switzerland’ are still quite important. On the contrary, questions about religion and Swiss ancestors play a minor role in considering a person to be a ‘true Swiss’. Only 39% and 42% of the respondents highlight their importance. Regarding the ‘birth place’ there is no clear tendency.

To test how many dimensions of national identity exist, we use principal component factor analysis of the 2003 EB data. In Table 3 three factors emerge with Eigenvalues above 1.

Table 3 about here

While the first two factors can be related to our theoretical concept of cultural and political national identity, the third factor builds an 'integration' dimension.

The first factor has an Eigenvalue of 3.12 and includes six items with high factor loadings. The item 'have Swiss ancestry' displays the highest factor loading and reflects a culturally exclusive conception of national identity because it cannot be acquired.

Other items as ‘birth place’, ‘spent time of life in country’ and ‘Swiss citizenship’ also load highly on the first factor. That 'Swiss citizenship', for example, is positively correlated with the first factor is surprising as it could also be referred only to access to the political process. Therefore, the assignment of items to specific dimensions depends on how the items are framed in a national context. The loading of these three items on

16

The comparison between the three language regions yields a similar result with exception of neutrality.

Only 75 % of the respondents of the French part of Switzerland and 63% of the Italian part think that neutrality is at least fairly important. The support of direct democracy is in all regions over 90% .

11

the cultural dimension could be explained with relation to the naturalization process.

Despite the political institutions and the linguistic diversity, Switzerland’s citizenship regime constitutes an ethnic-assimilationist type because it sets high barriers for migrants to access the political community (Koopmans et al. 2005, Kriesi & Helbling

2004). Framed in this manner, it is not exceptional that these items are part of the cultural and not the political dimension of national identity. To a certain degree the item

“feeling Swiss” displays this ambivalence between cultural and political component of national identity because it loads on the first as well as the third factor. As expected,

‘being Christian’ loads on the first factor and constitutes a cultural inclusive element of national identity. Even if one has to convert and assimilate to the Christian religion, it is at least feasible for everyone. Because this factor includes cultural exclusive as well as cultural inclusive items, it reflects a cultural dimension of national identity.

The second factor has an Eigenwert of 1.6 and includes items of the importance of the tree political institutions. The item about the ‘importance of federalism’, which displays the highest factor loading, is followed by the ‘importance of neutrality’ and ‘direct democracy’. Interestingly the ‘importance of neutrality’ also loads, though low, on the first factor. This finding could probably be explained by the different conceptions of neutrality, either passively as abstention from intervention in foreign politics or actively by emphasizing the humanitarian and diplomatic role of Switzerland in the world as initiated by foreign minister Micheline Calmy-Rey (Social Democrats). The former interpretation can be traced back to historical events in 1515 (Deutsch 1976, 41) and seems to be partly incorporated in a cultural conception of national identity, while the later interpretation is more recent and emphasizes a ‘cultural-free’ conception of national identity where human rights in general are central. This dimension nevertheless can be related to our theoretical conception of a pure political national identity. The importance of this factor is further enhanced by a clear tendency toward a political national identity shared by all Swiss citizens (see Table 2).

The third factor contains items as ‘speaking the national languages’, ‘respecting the political institutions’ and ‘feeling Swiss’. We would have expected especially the last two items to score high on the second factor because they represent typical characteristics of a ‘Willensnation’. But they measure a different dimension of national identity as the results show. Regarding the formulation of the items ‘ respect the political institutions’ and ‘able to speak one national language’, we suspect that they measure degree of integration.

We prefer this interpretation because these items refer rather to

12

the integration of a person in Switzerland than to the content of national identity. For example, while ‘speak a national language’ can only point to the degree of integration, a question about the importance of ‘multilinguism in Switzerland’ or ‘political institutions in general’ would have better captured the content of national identity. Because this factor does not refer to a specific content of national identity, we therefore exclude it from our further analysis.

To resume our results, first, we have found that the Swiss national identity not only contains a political, but also a cultural dimension. This result contradicts the theoretical expectation of Switzerland as a case with merely political national identity. Therefore, we can conclude that Switzerland is not as exceptional as generally believed. Also, other cross-national studies based on the ISSP data have found similar two-dimensional results by conducting factor analysis (Tilley et al. 2008, Hjerm 2003).

17 It should be mentioned, however, that the attachment to the political institutions still constitutes an important part of national identity. About 80% of the respondents consider the three political institutions to be at least fairly important.

Secondly, the respondents not only mainly agree about the importance of the political institutions, but also with regard to other questions items as ‘speak a national language’, to ‘respect political institutions’ and to have a ‘Swiss citizenship’. The latter is part of our cultural dimension. The attitudes toward importance of items, such as ‘have Swiss ancestry’, ‘born in Switzerland’ and ‘being Christian’, however, are not shared by all respondents. Therefore, we expect that Swiss citizens have different views about the content of cultural national identity and thus to be divided.

After having shown that at least two dimensions of national identity coexist and overlap, we want to explain the variance in the content of national identity. The two factors extracted from the factor analysis will be used as dependent variables. We hypothesize that party affiliation can explain this variance.

Explaining the national divide: Is it party affiliation?

The content of the national identity impacts on the definition of national interests. It determines, for example, who should be included and who excluded from policies, and what is seen as good or bad for the national community.

Because of this importance of

17 The factors found in these studies coincide with our cultural and integration dimension, because the general ISSP dataset does not include questions about the three political institutions.

13

the content of national identity, we expect the definition of the content of national identity to be highly politicized (see also Brubaker 1996). In particular, we expect that parties socialize “their” voters. On the other hand, different social groups vary in their

‘Weltanschauungen’ and interests, and might therefore demand different types of national identity. Parties consequently compete for the voters (also) on the issue of the content of national identity.

18 An implication thereof is that we expect the voters with the same party affiliations to share the same image about the content of the national identity. In what follows, we will make explicit what type of national identity we expect to be related to identification with which parties.

Party ideology and types of national identity

In what follows, we try to deduce the images of national identities that parties advocate from their main ideological premises. By doing this, we make explicit our assumptions about the parties’ stances on the political and cultural content of Swiss national identity.

We focus on the five largest Swiss parties after the parliamentary elections in 2007.

These are the Liberals (FDP), the Christian Democrats (CVP), the Swiss People’s Party

(SVP), the Social Democrats (SPS), and the Greens (GPS).

19

In Switzerland, as in other European countries, the Liberals were the early state- and nation-builders. Their political priority was to build a secular state that guaranteed religious tolerance. While initially democracy was not one of the priorities of the liberal camp at large, the Democratic Movement within the Liberals has pushed towards direct democracy. Despite the initial preference for a centralized state, the Liberals have increasingly appreciated federalism as a restraint to growing state intervention. The universality of the liberal ideals makes their proponents relatively resistant to a nationalism that refers to the specificity of the Swiss people in cultural terms.

Consequently, we expect the voters to be sympathetic to the Liberals, who share the image of the Swiss as a political nation.

The first challengers of the Liberals were the (Catholic) Conservatives. They in particular mobilized against anti-clericalism and centralism. In Switzerland the

Conservatives have consequently been the main advocates of federalism. Because the

18

As Kriesi at al. (2008) have shown, they clearly do on the salience of the national identity.

19

The labels correspond to the official short labels in German. At the time the survey was conducted the

Free Democrats and the Liberals were two parties. Meanwhile they fused and since then the official party label is ‘FDP.Die Liberalen’.

14

federal institutions have secured the influence of the Catholic Church on education in the Catholic cantons, the Conservatives did not have to push for a religious character of the state at the level of the central state. Because of the conservative worldview of an organic society and the “natural” differences between humans, one might associate a cultural image of the nation with the Christian Democrats. This conservative worldview is, however, balanced by the Christian Democrat’s appreciation of the role as mediator, which leads to its positioning in a largely non-ideological centre (Frey 2009, in particular 32-33, 102-131). Consequently, we expect the CVP’s voters to be moderate in their preference for a cultural national identity. Because of the Conservatives’ historical preference for federalism, we furthermore expect the political identity of their voters to be stronger.

Apart from the moderate conservative strand occupied by the Christian Democrats,

Switzerland knows a strong national-conservative camp. In the first half of the 20 th century it has to some degree been the equivalent of the Catholic conservatives in the

Protestant cantons. With the integration of the radical right forces since the 1960s, it contains, however, also an extreme right strand. It is in particular because of this strand that we expect its voters to advocate a cultural nationalism. Similar to the moderate conservatives, the national-conservatives advocated federalism as a means to restrict the influence of the state on society. Because of their strongly nationalist ideology, the national–conservatives have been particularly strong advocates of Swiss exceptionalism, which is most strongly symbolized through the (traditional) policy of neutrality. Consequently, we expect the voters of the national–conservatives, the Swiss

People’s Party (SVP), to imagine the Swiss as culturally homogeneous and sharing the same political principles.

Since the rise of the labour movement, the electoral strand of the Swiss left has been dominated by the Social Democrats. And just as in most other European countries, the

Swiss socialists split after the Second International into a Communist and Social

Democratic strand (Bartolini 2000). Despite their rejection of international communism, the Swiss Social Democrats have kept their international ideals. They have in particularly rejected a cultural nationalism, which in Switzerland has materialized in

Euroscepticism and anti-immigration sentiments (Kriesi et al. 2008). Its relation to a political national identity has remained more ambivalent. While the Social Democrats are skeptical towards federalism and traditional notions of neutrality (see above), they

15

have been more positive towards direct democracy which to some degree corresponds to Marxist ideas of radical democracy.

The Swiss Greens have their roots in an environmental movement that placed them on the centre-left. Since the 1990s the Greens have also attracted part of the alternative left, and meanwhile place themselves (at least) as left of the Social Democrats (e.g. Hug and

Schulz 2007). The Greens are, however, more post-materialist than the Social

Democrats and have even a stronger bias towards well educated ‘winners of globalization’. We expect the voters of the Greens, therefore, just as the Social

Democrats, to identify only politically with the Swiss nation.

Does party affiliation matter?

To explain diverging contents of national identity, we use regression analysis.

According to our hypothesis, we expect party affiliation to have an influence on the content of national identity. The resulting coefficients from the factor analysis are used to measure the dependent variable ‘content of national identity’. Our focus lies on the cultural and political dimension of national identity. The integration dimension is not considered in the analysis because it does not adequately capture the content of national identity (see above).

The independent variable ‘different political views’ is coded according to the mentioned party attachment of the respondents. Six different categories of party affiliation were created. They include the five largest parties – FDP, CVP, SPS, SVP and the GPS – and an additional category containing ‘other party preferences’. If the respondents have not acknowledged any inclination, they were classified as our reference category.

Furthermore, control variables are included in the analysis. To account for the hypothesis that different language groups identify distinctively with Switzerland, we use as linguistic proxy the first language spoken at home as indicated by the respondent.

20 According to the last chapter, we expect the linguistic proxy to have no influence on any content of national identity. The urban-rural cleavage is measured by the place of residence as proxy. The originally five categories were recoded into three: urban, town and village (reference category). Education is measured by the highest level attained and divided into three categories: primary school (reference category), secondary and tertiary. For both variables we anticipate a negative impact on the

20

If the first language was no national language or Romansh (N=2), we code according to the second language of the respondent.

16

cultural dimension, but no effect on the political dimension because educated and urbanized persons are less attached to cultural features but value more political participation. We control for gender as well. Then, attachment to the nation is considered. People that strongly identify with a nation are expected to identify themselves strongly with any content of national identity. Moreover, this indicator also controls for the possibly unintended effect of salience in the questions used as dependent variable. As indicator for religion we take the attendance of religious services and aggregate them into four categories, i.e. weekly, monthly, occasionally and never

(reference category). We expect religion as well as age to account for generational effects. While we predict that age is positively with both types of content, we predict that religious believers are generally more attracted to cultural contents, and nonbelievers rather to political contents of national identity. Finally, we control for

“migration background”. As a proxy we use parental citizenship with three categories: none parent citizen, one parent citizen and both parent citizens (reference category).

Because persons with migration background have been socialized within different cultures, we expect this indicator to have a negative impact on the cultural national identity. Since attachment to the political national identity is independent of any cultural experience, we anticipate a positive effect on the political dimension of national identity. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 about here

The first model, which only contains control variables, can account for almost 20% of the variance of cultural national identity. The strong urban-rural cleavage is confirmed in model 1. Persons who live in urban areas tend to score significantly lower on the cultural dimension of national identity than persons living in villages. The effect of residence in smaller towns is also negative, but not significant. The more frequent exposure to other non-Swiss cultures in urban areas could be a possible explanation.

The multinational hypothesis that different language regions vary with regard to the content of national identity has to be rejected with regard to significance. Though, the sign of these two coefficients point in different directions. While French-speaking Swiss identify less than German-speaking Swiss with the cultural national identity, Italianspeaking Swiss identify culturally even stronger. Higher education level – secondary and tertiary – has a negative and significant impact on cultural national identity. As

17

expected, persons that are very attached to Switzerland also have higher values of cultural national identity than less attached persons. The generation effect is also positive and significant. Age and religiosity, as expected, are positively and significantly related to cultural identity. The less cosmopolitan environments and the experience with specific contents of national identity – e.g. in school or national exhibitions – during socialization might serve as an explanation (cf. Helbling 1994).

Finally, also the size and the direction of the “migration background” dummies are according to our expectation. Persons with no Swiss parents or only one Swiss parent exhibit lower values on cultural identity. The size of those coefficients compared to the others is quite large and underlines their importance. Equal to the urban dummy, this proxy shows that contact with other cultures seems to have a negative effect on the cultural content of national identity.

The control variables in model 2 explain less than 5% of the variance of political content of national identity. No coefficient except the one measuring ‘attachment to

Switzerland’ is significant. This is not surprising considering the fact that more than

80% of the respondents have highlighted their importance (see Table 1). The result is nonetheless important because it shows that political attachment to the nation is not influenced by these control variables. Interestingly, the coefficient for both Italianspeaking and French-speaking Swiss are negative, i.e. they identify less with the political national identity. Also worth mentioning are the positive coefficients of

‘migration background’, though the coefficients are much smaller than in model 1.

People with migration background tend to have a less cultural, but more political concept of national identity.

Model 3 and 4 only take the party affiliation of the respondents into account.

According to Table 4, these variables can only explain a minor part of the variance of the content of national identity, almost 6% of the cultural and 1.4% of the political dimension. The direction of the coefficients with respect to the reference category – no party preference – is as expected. While the coefficient accounting for the Greens is negative and quite large, the coefficient representing attachment to the Swiss People’s

Party is also large but positive. Both coefficients are highly significant.

The coefficient of the Social Democrats is negative, but three times smaller than the coefficient for affiliation with the Greens and less significant. This result can be explained by the larger variance of persons attached to the Social Democrats in respect to their evaluation of the cultural dimension of national identity (see the Appendix).

18

Between the two extremes of weak and strong cultural identification lie the coefficients of the Liberals and the Christian Democrat voters. Both coefficients are positive but not significant. However, persons attached to these parties seem to identify themselves more with the cultural content of national identity than voters of the left.

In model 4 none of the coefficients are significant except the one that accounts for affiliation to the Swiss People’s Party. The order of the parties is almost the same as in model 3, the coefficient of the Liberals is higher than that of the Christian Democrats, but the differences between these coefficients have become smaller. This finding is also enhanced by Figure 1, which presents the average factor loading of both dimensions of national identity per party. The horizontal distance between the Swiss People’s Party and the Greens is twice the size of the vertical distance between these two parties. The picture also shows that there is almost no difference between the voters of the centerparties and the Social Democrats with regard to the content of national identity.

Figure 1 about here

Finally, model 5 and 6 contain the party affiliation as well as the control variables.

The differences compared to model 1 and 2 are only minor. The size of the party coefficients decreased by taking the other variables into account.

In model 5 only the coefficient of the Greens is significant, while no other coefficient that accounts for party affiliation is significant. Their order, furthermore, has changed.

Now the coefficient of the Christian Democrats displays a higher coefficient than the coefficient of the Liberals with regard to cultural national identity. The significance and the size of the coefficient of the control variables have only changed little compared to model 1. Party affiliation, therefore, seems to have an impact, but only a small one. This finding is also confirmed by the only modestly higher adjusted R 2 (+0.8%).

The results of Model 6, which explains the identification with the political dimension of national identity, have neither changed significantly compared to model 2. The coefficient of the Swiss People’s Party, however, is still highly significant and positive.

Persons attached to this party tend to value political national identity higher than persons that are not at all attached to a specific party. With regard to the control variables, neither the significance nor the direction of the coefficients have changed, but

19

in general the size has decreased. Therefore, we can also conclude that party affiliation matters, but not very much.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the notion that the Swiss are a political nation is only partially true. While it is correct that there is a national consensus on political values, there is none concerning cultural identity. Switzerland, then, seems to provide evidence for those who argue that a political national identity may suffice to grant state integrity and national solidarity. The findings suggest that this is even possible if a nation is divided on its cultural features.

However, a cautionary remark on this result should be made. The questions asked in the survey might only partly be able to measure the cultural dimension of the Swiss identity. There is in particular one feature of the Swiss identity that might be relevant here, which has not been measured. This concerns the Swiss’ pride about cultural pluralism. The argument here is not that the Swiss are simply proud of being able to live peacefully together despite cultural fragmentation, but that the citizens appreciate

Switzerland‘s large variance between cantons and language regions. It is this image of the Swiss as a people that is able to speak various languages and has internalized different cantonal cultures which might be part of the cultural dimension of Swiss national identity. It seems to us that the question whether this ‘pluriculturalism’ is an important part of the Swiss identity merits further investigation.

Additionally, while the paper argues that party identification is an important predictor concerning the images of national identity, it remains open whether the parties do advocate the same frames as their voters. Evidence about the importance of the framing of the national identity on the party system can, however, only be gained by focusing more narrowly on the political offer parties present.

20

References

Abizadeh. Arash. 2002. Does Liberal Democracy Presuppose a Cultural Nation? Four

Arguments. American Political Science Review 96(3): 495–509.

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origins and

Spread of Nationalism . London: Verso. [Revised edition].

Bartolini, Stefano. 2000. The Political Mobilisation of the European Left, 1860-1960.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bendix, Regina. 1992. National Sentiment in the Enactment and Discourse of Swiss

Political Ritual. American Ethnologist 19(4):768-790.

Berthoud, Gérald. 2001. The ‘spirit of the Alps’ and the making of political and economic modernity in Switzerland. Social Anthropology 9(1): 81–94.

Bhattacharyya, Harihar. 2007. India and Switzerland as Multinational Federations. In

Michael Burgess and John Pinder (eds.): Multinational Federations, Vol. 16.

London: Routledge.

Brubaker, Rogers. 1996. Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brubaker, Rogers. 1999. The Manichean Myth: Rethinking the Distinction between

‘Civic’ and ‘Ethnic’ Nationalism. In Kriesi et al. (eds.): Nation and national identity: the European experience in perspective.

Chur and Zurich: Rüegger.

Chandra, Kanchan. 2006. What is ethnic identity and does it matter? Annual Review of

Political Science 9:397-424.

Christin, Thomas and Alexander Trechsel. 2002. ‘Joining the EU? Explaining Public

Opinion in Switzerland’. European Union Politics 3(4): 415–43.

Dardanelli, Paolo (forthcoming). Multi-lingual but Mono-national. Exploring and

Explaining Switzerland’s Exceptionalism. In Miquel Caminal and Ferran Requejo

(eds.): Democratic Federalism and Multinational Federations . Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Autònomics, 1–32.

Deutsch, Karl. 1976. Die Schweiz als ein paradigmatischer Fall politischer Integration .

Bern: Verlag Haupt.

Erk, Jan. 2003. Swiss Federalism and Congruence. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics

9(2): 50–74.

Frey, Timotheos. 2009. Die Christdemokratie in Westeuropa. Der schmale Grat zum

Erfolg. Zürich: Nomos.

21

Froidevaux, Didier. 1997. Construction de la nation et pluralisme suisse: idéologies et pratiques. Revue suisse de science politique 3(1): 29–58.

Gellner, Ernest. 1983. Nations and Nationalism . Ithaca, New York: Cornell University

Press.

Greenfeld, Liah. 1999. Is Nation Unavoidable? Is Nation Unavoidable Today? In Kriesi et al. (eds.): Nation and National Identity; The European Experience in Perspective .

Chur und Zürich: Rüegger.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1990. Staatsbürgerschaft und nationale Identität. In Jürgen Habermas

(ed.) 1992: Faktizität und Geltung . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 632–60.

Heath, A. F. and R. Tilley. 2005. National Identity and Attitudes Towards Migrants –

Findings from the ISSP . International Journal on Multicultural Societies 7:2, 119-

132.

Helbling, Barbara. 1994 . Eine Schweiz fur die Schule. Nationale Identitat und kulturelle

Vielfalt in den Schweizer Lesebuchern seit 1900 . Zurich: Chronos.

Helbling, Marc and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2004. Staatsbürgerverständnis und politische

Mobilisierung: Einbürgerungen in Schweizer Gemeinden. Swiss Political Science

Review 10(4): 33–58.

Hjerm, Mikael. 2003. National sentiments in Eastern and Western Europe. Nationalities

Papers 31(4): 413–29.

Hobsbawn, Eric J. 1992 [1990]. Nations and nationalism since 1780. Programme,

Myth, Reality . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Revised edition].

Hobsbawm, Eric J. and T. Ranger. 1992. The Invention of Tradition.

Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Hug, Simon and Tobias Schulz. 2007. Left-Right Positions of Political Parties in

Switzerland. Party Politics 13(3), 305-330.

Huntington, Samuel P. 2004. Who are we? The Challenges to America’s National

Identity.

New York: Simon & Schuster.

Ipperciel, Donald. 2007. La Suisse: un cas d’exception pour le nationalisme? Revue suisse de science politique 13(1): 39–67.

Jones, Frank L. and Philipp Smith. 2001. Diversity and commonality in national identities: An exploratory analysis of cross-national patterns. Journal of Sociology

37(1): 45–63.

Kohn, Hans. 1956. Nationalism and Liberty: the Swiss Example . London: Allen and

Unwin.

22

Koopmans, Ruud, Paul Statham, Marco Giugni and Florence Passy. 2005. Contested

Citizenship. Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kreis, Georg. 1989. Der ‘homo alpinus helveticus’. Zum schweizerischen

Rassendiskurs der 30er Jahre. In Guy P. Marchal and Aram Mattionli (eds.).

Erfundene Schweiz. Konstruktion nationaler Identität . Zürich: Chronos Verlag.

Kriesi, Hanspeter. 1999. Introduction: State Formation and Nation Building in the Swiss

Case. In Hanspeter Kriesi, Klaus Armingeon , Hannes Siegrist and Andreas

Wimmer (eds.): Nation and National Identity . Chur and Zurich: Rüegger, 13–28.

Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2002. Politische Folgen nationaler Identität. In Catherine B.

Bosshart-Pfluger, Joseph Jung and Franziska Metzger (eds.): Nation und

Nationalismus in Europa. Kulturelle Konstruktion von Identitäten. Festschrift für

Urs Altermatt.

Frauenfeld: Huber, 565–86.

Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2007a. Die Schweiz – ein Nationalstaat? In Thomas Eberle and Kurt

Imhof (eds.). Sonderfall CH . Zürich: Seismo Verlag, 82–93.

Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2007b. The Role of European Integration in National Election

Campaigns. European Union Politics 8 (1): 83–108.

Kriesi, Hanspeter, Boris Wernli, Pascal Sciarini and Matteo Gianni. 1996. Le clivage linguistique. Problèmes de compréhension entre les communautés linguistiques en

Suisse . Berne: Office fédéral de la statistique.

Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier and Timotheos Frey 2008. West European Politics in the Age of Globalization .

Cambridge University Press.

Kriesi, Hanspeter and Alexander Trechsel. 2008. The politics of Switzerland. Continuity and Change in a Consensus Democracy . Cambridge University Press.

Kymlicka, Will. 1995 . Multicultural Citizenship . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kymlicka, Will. 2001. Politics in the Vernacular . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McRoberts, Kenneth. 2001. Citizenship and National Identity. Canadian Journal of

Political Science 34(4): 683–713.

Mill, John Stuart. 1977 [1865]. Considerations on Representative Government. In J.M.

Robson (ed.): Collected Works of John Stuart Mill . Toronto: University of Toronto

Press.

Miller, David. 1995. On Nationality . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

23

Mottier, Véronique. 2000. Narratives of national identity: Sexuality, race, and the Swiss

‘dream of order’. Swiss Journal of Sociology 26: 533–58.

Mottier, Véronique. 2008. Eugenics, politics and the state: social democracy and the

Swiss ‘gardening state’.

Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and

Biomedical Science 39: 263–9.

Müller, Christine. 2008. Images of Switzerland at the World Fairs – Ephemeral

Architecture as a Symbol for National Identity? In: Herrle, Peter and Erik

Wegerhoff (eds.): Architecture and Identity . Berlin: LIT, 113–22.

Nieguth, Tim. 1999. Beyond dichotomy: concepts of the national and the distribution of membership.

Nations and Nationalism 5(2): 155–73.

Renan, Ernest. 1996 [1882]. Qu'est-ce qu'une nation ? Paris: Mille et une nuits.

Rutschmann, Verena. 1994. Fortschritt und Freiheit. Nationale Tugenden in historischen Jugendbüchern der Schweiz seit 1880 . Zurich: Chronos.

Santschi, Catherine. 1991. Schweizer Nationalfeste im Spiegel der Geschichte . Zurich:

Chronos.

Sciarini, Pascale, Simon Hug and Cédric Dupont. 2001. Example, Exception or Both?

In Lars-Erik Cederman: Constructing Europe's Identity. Issues and trade-offs.

Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 57–88.

Seton-Watson, Hugh. 1977. Nations and States . London: Methuen

Shulman, Stephen. 2002. Challenging the civic/ethnic and West/East dichotomies in the study of nationalism. Comparative Political Studies 35(5): 554-585.

Smith, Anthony D. 1986. The Ethnic Origins of Nations . Oxford: Blackwell.

Stojanovic, Nenad. 2003. Swiss nation-state and its patriotism. A critique of Will

Kymlicka’s account of multinational states. Polis 11: 45–94.

Tilley, James, Anthony Heath and Robert Ford. 2008. The long shadow of history: The effects of economic development and ethnic diversity on national identity. CREST

Working paper 111, April 2008.

Torriani, Riccarda. 2002. The Dynamics of National Identity: A Comparison of the

Swiss National Exhibitions of 1939 and 1964. Journal of Contemporary History

37(4): 559–73

Zimmer, Oliver. 1998. In Search of Natural Identity: Alpine Landscape and the

Reconstruction of the Swiss Nation. Comparative Studies in Society and History

40(4): 637–65.

24

Table 1: Salience of identities among Swiss language groups

How close do you feel to Switzerland?

Very close

Close

Not very close

Not close at all

French speakers

43.4

42.8

10.4

3.5

Italian speakers

40.5

46.0

10.8

2.7

German speakers

46.8

47.9

5.2

0.1

N 173 37 725 935

Note: Only Swiss citizens, respondents with non-national language as first language were coded according to second language, Romansh speakers (N=2) also.

Source: Swiss Eurobarometer 2003.

Total

45.9

46.8

6.4

0.9

25

Table 2: Questions from the ISSP and EB 2003

How important is… 1 direct democracy

Neutrality

Federalism

What is important to be a true

Swiss...

2 respect Switzerland's institutions & laws able to speak the national languages have citizenship of Switzerland feel Swiss spend most life in Switzerland born in Switzerland

Not important at all

0.2

3.0

2.4

1.0

0.3

4.2

4.6

7.2

15.3

Not very important

4.0

17.7

17.5

3.0

7.1

15.0

18.9

26

30.9

Fairly important

30.2

35.4

50.9

60.6

40.2

38.1

44.5

41.3

31.1

Very important

65.6

43.9

29.3

35.5

52.4

42.7

32.0

25.5

22.6

At least fairly important

95.8

79.2

80.1

96.0

92.6

80.8

76.5

66.8

53.8

N

930

930

916

933

930

929

919

930

919 have Swiss ancestry 23.1 34.8 27.7 14.3 42.1 913 being a Christian 32.5 28.1 22.7 16.6 39.4 919

Note: Modal categories are underlined.

Original questions:

1 Some people say that the following things are important for being truly Swiss. Others say that they are not important. How important do you think each of the following is [Very important/ Fairly important/ Not very important/ Not important at all/ Can’t choose]?

2 How important – from your point of view – are these three political institutions for the future of our country

[Very important/ Fairly important/ Not very important/ Not important at all]?

Source: Swiss Eurobarometer 2003.

26

Table 3: Varimax rotated factor matrix for items concerning national identity

Variable

Importance of federalism

Importance of direct democracy

Importance of neutrality have Swiss ancestry born in Switzerland spend most time of life in Switzerland being Christian have the Swiss citizenship feel Swiss respect institutions & laws of Switzerland able to speak one of the national language

% of variance explained

Eigenvalue

N

Note: cut-off point 0.25.

Source: Swiss Eurobarometer 2003.

Factor 1

0.271

0.820

0.790

0.699

0.683

0.681

0.530

57.32

3.12

Content of identity

Factor 2

0.776

0.706

0.637

1.60

813

Factor 3

0.482

0.807

0.749

1.58

27

Table 4: Determinants of national identity

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6

Dependent variable

Greens

Social Democrats

Liberals

Christian Democrats

Swiss People’s Party

Other parties

Urban

Town

French Switzerland

Italian Switzerland

Secondary education

Tertiary education

Gender

Attachment to

Switzerland

Age

Church attendance, weekly

Church attendance, monthly

Church attendance, occasionally

One parent Swiss citizen

No parent Swiss citizen

Constant

Cultural

-0.444***

(0.105)

-0.053

(0.080)

-0.131

(0.090)

0.211

(0.166)

-0.287*

(0.115)

-0.600***

(0.137)

-0.026

(0.066)

0.222***

(0.051)

0.011***

(0.002)

0.304*

(0.127)

0.105

(0.102)

0.150*

(0.072)

-0.354**

(0.128)

-0.700***

(0.123)

Political

-0.120

(0.115)

0.028

(0.087)

-0.138

(0.098)

-0.220

(0.182)

-0.054

(0.126)

0.000

(0.150)

-0.021

(0.072)

0.288***

(0.056)

0.003

(0.002)

0.005

(0.139)

0.019

(0.111)

0.155

(0.079)

0.055

(0.140)

0.082

(0.135)

-0.885** -1.098***

Cultural

-0.763***

(0.149)

-0.204*

(0.100)

0.109

(0.111)

0.275

(0.161)

0.008

Political

-0.123

(0.153)

-0.055

(0.102)

0.168

(0.114)

0.039

(0.164)

0.495*** 0.493***

(0.135)

0.171

(0.212)

(0.138)

0.160

(0.217)

-0.046

0.199***

(0.052)

0.010***

(0.002)

0.284*

(0.132)

0.085

(0.102)

0.147*

(0.072)

-0.330*

(0.128)

-0.678***

(0.123)

0.090

0.276***

(0.057)

0.002

(0.002)

-0.008

(0.144)

-0.001

(0.112)

0.153

(0.079)

0.073

(0.141)

0.104

(0.135)

0.235

(0.253) (0.277) (0.047) (0.048) (0.199) (0.218)

F Value

N

15.09

811

3.26

811

9.11

813

2.87

813

11.37

811 adj. R 2

0.196 0.038 0.057 0.014 0.204

Note: unstandardized coefficients, standard errors in parentheses; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

2.83

811

0.043

-0.391***

(0.106)

-0.033

(0.080)

-0.120

(0.090)

0.216

(0.168)

-0.275*

(0.115)

-0.553***

(0.138)

-0.003

(0.067)

Cultural

-0.406**

(0.142)

-0.140

(0.094)

-0.014

(0.108)

-0.031

(0.156)

0.215

(0.128)

0.090

(0.199)

-0.107

(0.117)

0.041

(0.087)

-0.131

(0.098)

-0.240

(0.184)

-0.066

(0.127)

0.011

(0.151)

0.012

(0.073)

Political

0.002

(0.155)

-0.069

(0.102)

0.053

(0.119)

-0.037

(0.171)

0.402**

(0.140)

0.235

(0.218)

28

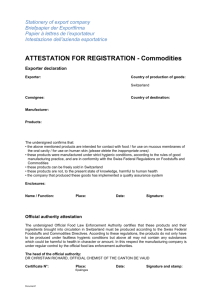

Figure 1: Values on identity dimensions according to party affiliation

29