The Stranger Annotation Guide for High School Students

advertisement

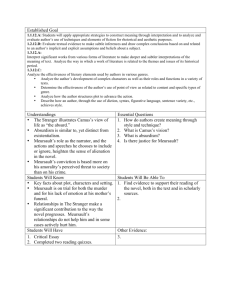

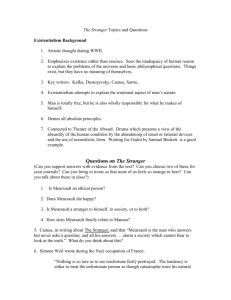

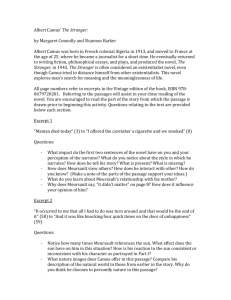

Annotation Questions for Camus’s The Stranger (Rising 12th Grade) Please buy THIS text: http://www.amazon.com/Stranger-AlbertCamus/dp/0679720200/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1432041757&sr=11&keywords=camus+the+stranger Annotation Instructions: As you read Camus’s The Stranger, choose three of the five questions below to guide your annotations of the novel. That is, record comments in the margins of your text that help you address or consider your chosen questions. Below are some handy hints for creating meaningful annotations. Why should I annotate? How do I annotate? (1) On the whole, QUALITY is more important than QUANTITY; thorough annotations every five pages will help you engage with and process the novel more meaningfully than scribbling single words on every page. As a reader, you’re in conversation with the text. Books speak to us; speak back to them. Writing too many comments is the equivalent of annoying small talk. (3) Make connections or comment on patterns that exist across the text. When asked his advice about what novelists need to do to be great, the superb British novelist E.M. Forester wrote: “Connect, connect, connect.” His answer is a bit of a pun: he means that an author must connect with his audience. But he also means to connect every aspect of the novel together: in great art, meaning exists everywhere. Novels are spider webs of ideas and feelings. Draw the web. When you note something (a symbol, an image, a character trait) early in the novel, see if you can reconsider that notion if and when it reappears. The questions below will help you do just that. (4) Avoid writing down single literary terms like “symbol,” “theme,” or “imagery.” Talk about the book—not around it. Those terms don’t really help you make any sense of anything unless you comment more deeply about them. First, notice things—but then try to explain or describe them. (5) Personal comments (“Cool!” “Weird!” “I don’t get this!”) won’t really help you make sense of the book. Avoid them. Personal reactions are lovely—that’s why we read!—but they’re not the stuff annotations are made of. If you’re compelled to write such comments, follow them up with legitimate questions or comments that address the questions you’ve chosen. Questions: 1. The English word “strange” comes to us via the Old French estrange from the original Latin extraneus, i.e., “eternal, “strange.” In fact, the Old French word in modern English is a verb that means to “alienate,” “to “turn off,” “to antagonize,” or “to drive away.” When we see the English word “strange,” we think “atypical” or “odd.” It’s a word with pejorative connotations. As children we’re taught to be wary of strangers. Most of us don’t want people to think of us as strange. As you read Camus’s novel, in your annotations focus on how the protagonist Meursault’s behavior is out of the ordinary. How is he a “stranger,” how is he “estranged,” and how does he estrange others? 2. Albert Camus, an atheist, argued in his essay “The Myth of Sisyphus” that life is absurd in that even though human beings yearn for some ultimate meaning of existence, the universe itself is absolutely indifferent, devoid of meaning; therefore, life is absurd. Camus believed in the face of this absurdity humans must find for themselves what makes them happy. As you read and annotate The Stranger, pay close attention to and comment on what brings the protagonist Meursault happiness and how his pursuit of happiness is similar to and/or different from the other characters in the novel. 3. Meursault, the protagonist of The Stranger, is a very passive character. As you read and annotate the novel, pay attention to and comment on instances of Meursault’s passivity. 4. Though he wasn’t a philosopher in the scholarly sense, Camus subscribed to the philosophical school called existentialism. Existentialism is a complex set of ideas that means different things to different people, but most existentialists embrace these principles: (1) Who you are is primarily defined by how you act (your existence) rather than by who you supposedly are “on the inside” (your essence). “Existence,” according to this view, “precedes essence.” (2) There are no absolute, instrinsic ideas or values that make life meaningful. (3) A person who recognizes that life isn’t instrinsically meaningful must accept the terrifying possibility that nothing matters in life, that all is “nothingness.” (4) However, once one refuses to accept any established beliefs at face value, one is free to find personal meaning in life, to write new scripts for one’s life after throwing away the pre-written ones. Unlike his author, Meursault seems unaware on an intellectual level of the ideas associated with existentialism. However, as you track his thoughts and actions, does he come across as a kind of instinctive, unconscious existentialist? Where and how do you see him not accepting, or even recognizing, the basic standards and values that the people around him take for granted? On the other hand, do you see any evidence in his thoughts and actions of personal values or beliefs that make life meaningful for him? 5. Throughout The Stranger, Meursault is judged, very often disapprovingly, by others. How, why, and by whom (especially in the first half of the book) do you see him being judged for his social attitudes and actions by people who know or encounter him? Once he’s arrested on a charge of murder, by whom do you see him being judged for his criminal actions and motives? What connections do you see between those social and those criminal judgments ? Once the murder trial begins, how and why do those two types of judgment become bound up together?