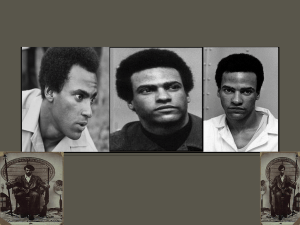

Hystericizing Huey: Emotional Appeals, Desire, and the

advertisement