Week 6 notes : Continuous random variables and their probability

advertisement

Week 6 notes : Continuous random variables and their probability densities

WEEK 6 page 1

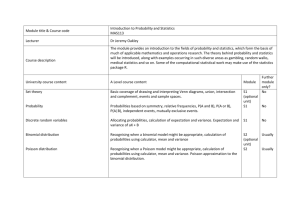

uniform, normal, gamma, exponential,chi-squared distributions, normal approx'n to the binomial

Uniform [0,1] random variable : For a simple example of a continuous random variable we consider

choosing a value between 0 and 1 (hence lying in the interval [0,1] ) in which any real number in this

interval is equally likely to be chosen. To obtain such a uniform [0,1] random variable we define the

probability P a X b that X lies between the values a and b with 0≤ab≤1 to be the portion

of the area lying between the values x = a and x = b under the curve having constant height 1 for x

between 0 and 1 and height 0 elsewhere f x =1 if 0≤x≤1 ( f x =0 elsewhere ) . In this way

the probability only depends on the length b−a of the sub-interval [a,b] hence is uniformly spread

over the interval [0,1].

Uniform [a,b] random variable : Generalizing this we can next consider a uniform [a,b] random

variable as one having density which is constant on the interval [a,b] and 0 elsewhere. The constant

1

for axb is determined from the condition that the total area under the

density f x =

b−a

density curve y= f x (= total probability) equals 1. ( rectangle of width b−a having area 1

determines the height f x of the rectangle )

Probability density function : An arbitrary continuous random variable X is similarly described by its

probability density function f x = f X x meaning again that the probability that X lies between

two values a and b is the integral of the density f x on this interval which is the area under the

density curve. In symbols

b

P a≤ X ≤b=∫ f x dx = area under the curve y = f x between a and b .

a

We can regard this as the probability measure of the set (event) which is the interval [a , b ] . There

will in general be certain sets which can not be obtained as countable unions or intersections of

intervals for which one is not able to define a probability. However in practice this rarely comes up.

(Technically the sample space can be abstract and what we have really defined is the probability (acting

on the actual sample space ) of the inverse of the function X . This inverse maps from the reals back to

the sample space. This induces a probability measure P X −1 defined on sets of reals and so for all

practical purposes we can view events as sets of real numbers without loss of generality. )

For a continuous random variable the probability that X equals any particular value is 0 since according

to our above definition this is P X =a= P a≤ X ≤a which is given by the integral of the density

f x from a to a which is 0 . Consequently for a continuous random variable, whether we include

an endpoint of an interval or not in calculating the probability makes no difference :

P a≤ X ≤b= P aX b .

Since probabilities are determined by densities and visa versa, from our axioms of probability we must

require that

1) 0≤ f x (the density is non-negative)

∞

2)

∫ f x dx =1

The first requirement is to insure that we don't get negative probabilities

−∞

which are forbidden, and the second just says that the total probability is 1 .

The interpretation of the density is that it gives the local probability per unit length along the x-axis

in the sense that for x lying in a small enough interval say [a , a x ] of width x provided the

density is a continuous function at x=a , the probability is approximately

f a⋅ x≈ f x ⋅ x that the random variable X lies in this interval :

WEEK 6 page 2

a x

P aX a x =

∫

f x dx ≈ f x⋅ x for x near a .

a

Said differently, if we define the (cumulative) distribution function (cdf )

x

F x=F X x=P X ≤x= ∫ f t dt

−∞

(Johnson just calls it the distribution function) for which one easily verifies that

F b−F a=P a X ≤b

(i.e. area to the left of b under the density curve minus area to the left of a equals area between a and

b)

then by the fundamental theorem of calculus, the derivative of the cdf F x is just the density

f x :

F a x− F a

P a X a x

d

F x = f x = lim

= lim

dx

x

x

x 0

x 0

where we have recalled the definition of the derivative of F x . We see that the above

approximation for the probability holds exactly in the limit x 0 .

Definition of expected value of X : The main change in passing from discrete to continuous random

variables is the replacement of the discrete sum by the continuous integral. For a continuous random

variable X with density f x , the expected value is defined as

∞

=E [ X ]=∫ x f x dx

−∞

and one can show that for any random variable which is a measurable function h X of the random

variable X (which we won't define precisely here but which will be the case for almost any function

occurring in practice) the expected value is

∞

E [ h X ]= ∫ h x f x dx .

−∞

In particular this gives for the variance the formula

∞

∞

V X =E[ X− ]=E [ X ]− since E[ X− ]= ∫ x− f x dx=∫ x 2 f x dx−2 =E[ X 2 ]−2

2

2

2

2

2

−∞

−∞

EXAMPLE 1 : (like HW problems 5.2, 5.3, 5.13 ) : Consider a random variable X having the density

function f x=k x 5 for 0 x1 ( f x=0 else ).

1

2

a) Find the constant k which makes this a density and then find P X :

3

3

1

k

5

The requirement that the total probability is 1 translates as 1=k ∫ x dx=

which gives k =6 .

6

0

2 /3

1

2

2 6 1 6 7

P X =∫ 6 x 5 dx= − =

.

3

3 1 /3

3

3

81

b) Find the mean and variance of X :

1

1

6

5

6

E [ X ]=∫ x⋅6x dx=∫ 6 x dx= .

7

0

0

1

E [ X 2]=∫ 6 x 7 dx=

0

Thus

3

.

4

WEEK 6

page 3

2

3 6

3

2 =E [ X 2 ]− 2= − =

4 7

196

gives the variance.

c) Find the cumulative distribution function of X :

x

F x =∫ 6 t 5 dt = x 6 for 0x1

0

(

F x=0 for x≤0 and F x =1 for x≥1 )

d) Using this distribution function find

Also find

P .3 X .5 :

5 6

3 6

P .3 X .5=F .5−F .3= − =.014896

10

10

P X .9 :

6

9

P X .9=1−P X ≤.9=1−F .9=1− =.468559

10

A Standard Normal random variable Z is one with mean 0 and variance 1 having density given by

the symmetric bell-shaped curve :

f x ;0, 1=

1 −x /2

e

.

2

2

For such a normally distributed random variable we write

Z ~ N(0,1) .

It is common to use the letter Z to indicate a standard normal.

Normal random variable : A random variable X has normal distribution with parameters mean

and variance 2 , in symbols

X ~ N , 2

if its density is of the form

f x ; , 2 =

1

e−x− /2

2

2

2

One can show by the definition of expected value that the parameters and 2 really do give the

mean and variance of this density.

It is a fact that if X ~ N , 2 is normally distributed with parameters and 2 then the

standardized random variable

X −

Z =

~ N 0,1

has a standard normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1.

That we get the stated mean and variance is because constants factor outside expectations and the

expected value of a sum or difference is the sum or difference of the expected value so that

X − 1

E[

]= E [ X ]− =0 since E [ X ]= .

Also using the definition of the variance , we find that when computing the variance of a constant times

a random variable, the constant gets squared before pulling it outside the variance WEEK 6

so that

X −

1

V[

]= 2 V [ X −]=1

2

as claimed ( since V [ X −]=V [ X ]= )

page 4

To see that the distribution is still in fact normally distributed, observe that the cumulative distributions

of the random variables Z and X are related by :

X −

F Z z =P

z =P X z =F X z =F X x

where x= z . Then by the chain rule, and noting that x−2 / 2 2 = z 2 /2 one has

d

d

dx

1

1 −z / 2

f Z z= F Z z = F X x =

e−z / 2⋅=

e

dz

dx

dz 2

2

2

2

which is the standard normal density.

1

is the correct one to use in the standard normal

2

There is a trick used to show that the constant

density. Writing

∞

2

I =∫ e−x / 2 dx

−∞

One notes that this integral stays the same when one changes the dummy variable of integration from x

to y so that one has

∞

I =∫ e

2

2

−x /2

∞

dx ∫ e

−∞

2

− y /2

∞

dy =

−∞

∞

2

2

∫ ∫ e− x y / 2 dy dx

−∞ −∞

Re-arranging the order of integration can be done since the y integral is a constant with respect to x .

But now if we change to polar coordinates for the radius r going from 0 to ∞ one has

x 2 y 2=r 2

and after breaking up the plane into circular donut shaped annulus regions of radius r and

infinitesimal thickness dr and integrating out the angle the area element dx dy turns into

2 r dr so we find the above integral becomes

∞

2

I 2 = 2∫ e−r /2 r dr = 2

0

which verifies the claim since we must choose the constant k so that kI = 1 .

That the mean of the standard normal is 0 is a consequence of symmetry since

∞

2 ⋅E [ X ]=∫ x e

−∞

2

−x /2

dx=lim

0

∫ xe

R ∞ −R

2

−x / 2

R

2

dx∫ x e− x / 2 dx = 0

0

(To see that the first integral on the right is minus the second we change variable from x to -x in that

integral yielding the product of 3 minus signs which is an overall minus the 2nd integral : the first minus

comes from replacing x by -x , the second by replacing dx by – dx and the third because the limits of

integration for -x have changed from -R to 0 for x to R to 0 for -x which requires the interpretation that

we must add a minus sign when flipping the limits from R to 0 back to 0 to R. )

To see that the variance of the standard normal really is 1 , since the mean is 0 the variance is just

∞

2

I =E [ X 2] where 2 I = ∫ x 2 e−x /2 dx & we can either do a polar coordinate trick WEEK 6 page 5

−∞

2

∞

2

2 −x / 2

2 I =∫ x e

−∞

∞

2

2 −y /2

dx ∫ y e

∞

∞

2

dx=∫ ∫ x y e

−∞

2

2

2 − x y / 2

2 ∞

2

dy dx=∫ ∫ rcos 2 rsin 2 e−r /2 r dr d

0

−∞ −∞

0

like we did before { but this now involves an integration over the angle and requires the trig

identities

sin 2 =2 sin cos and sin2 2 =1−cos 4 /2

This cos 4 term vanishes (gives 0) after doing the integration. One changes variables to

u=r 2 /2 so du=r dr . This is a good exercise in integration. }

or : However it is considerably easier to simply integrate by parts, namely

∞

∞

2

2

2 2=∫ x 2 e−x / 2 dx=∫ x⋅d −e−x /2

−∞

−∞

2

is of the form for which integration by parts applies with u=x and v=−e−x / 2 so that using

∫ u dv=uv −∫ v du now the uv term vanishes at the limits of integration so the integral reduces to

∞

2

2 =∫ e −x / 2 dx / 2 =1 since this is just the total area under the standard normal curve which we

−∞

know equals 1. (This integral was evaluated earlier by the polar coordinate trick above.)

To see the mean of the normal distribution is really we have

∞

2

2

E [ X ]= ∫ x e− x− /2 dx / 2

−∞

which by the change of variables

∞

=

2

z= x−/ hence dx= dz becomes

∞

∞

2

2

∫ z e−z / 2 dz / 2 = ∫ z e−z / 2 dz / 2 ∫ e−z / 2 dz / 2 = 0⋅1=

−∞

−∞

−∞

which proves the claim since we already saw that the first integral on the right vanishes by symmetry

and the second is just the total area under the standard normal curve which is 1.

To see that the variance of the normal distribution really is 2 , we have

∞

2 − x−2 / 2 2

V [ X ]=∫ x− e

dx / 2

−∞

which by the same change of variable as above becomes

∞

=

2

∫ z 2 e−z / 2 dz / 2

−∞

∞

2

= 2 ∫ z 2 e− z /2 dz / 2 = 2

−∞

since the rightmost integral is just the variance of the standard normal which we have seen is 1.

EXAMPLE 2 : a) Problem 5.31 from the text : The specifications for a certain job calls for washers

with an inside diameter of .300±.005 inch . If the inside diameter is normally distributed with mean

=.302 and standard deviation =.003 what percentage of the washers will meet the

specifications?

Let

X = inside diameter of a randomly selected washer

X −.302

Then the standardized variable Z =

will be standard normal N(0,1)

.003

The question translates into what is the probability

P .300−.005 X .300.005

WEEK 6 page 6

.300−.005−.302

X −.302 .300.005−.302

Z =

.003

.003

.003

= P −7/ 3Z 1= F 1−F −2.333=.8413−.0098=.8315=83.15%

= P

Note that in using the cumulative distribution function for the standard normal given in table 3 of

Appendix B at the back of the book, the more accurate value .0098 for F(-2.333) is obtained by linear

interpolation of the values F( -2.33 ) =.0099 and F( - 2.34 ) = .0096 since it lies one third of the way

between these two and one third of .0003 is .0001 which we subtract from .0099.

b) For the above problem, for what value of the inside diameter is the probability 98% that the washer's

inside diameter will exceed this value ?

x 0 say for which P X x0 =.98 or equivalently we first find

x −.302

X −.302

the standardized value z 0= 0

for which the standardized variable Z =

satisfies

.003

.003

P Zz 0=.98 . Then we have P Z≤z 0=1−.98=.02 which from table 3 of Appendix B is the

linear interpolation between P Z −2.05=.0202 and P Z −2.06=.0197 The value .02 is .0002

less than the first value which lies .0005 above the 2nd value so we want to go 2/5 or 4 tenths of the way

between the two values or z 0=−2.054 which says

x 0=.003⋅z 0.302=.003⋅−2.054.302=−.006162.302=.2958 inch

c) What is the probability that the inside diameter is at least .305 ?

X −.302 .305−.302

P X .305=P Z =

=1 = P Z 1 = 1− P Z 1

.003

.003

= 1−.8413=.1586 or 15.86

Note that by the symmetry of the standard normal curve, we could have also obtained the answer via

P Z1=P Z−1=.1586

which can be found directly from table 3.

We wish to find the diameter

Had we asked what is the probability that the inside diameter is at most .305 we would have wanted

P X .305=1−P X .305= P Z 1=.8413

Note that the event that a standard normal lies at least 1 standard deviation from the mean has double

the probability that the inside diameter is at least .305, namely

P Z −1 or Z1=2P Z −1=2.1586=.3172

Review question : For a Poisson random variable with parameter

deviation ?

=5 what is the standard

The parameter for a Poisson equals both the mean= 5 and the variance =5 so the standard deviation of

this is by definition just the square root of the variance which is 5 .

Recall the above Poisson random variable has distribution

The z-critical value

by

P X =k =

5 k −5

e .

k!

z is the 1001− percentile of the standard normal distribution defined

=P Z z

so that 1−=P Z≤ z . That is is the area under the standard normal curve WEEK 6 page 7

to the right of z and 1− gives the area to the left of z . By symmetry of the standard

normal curve the z-value for which the area to the left of this value is (hence the area to the right is

1− ) is

z 1− = − z

From table 3 of Appendix B we find

z .01=2.33 and z .05=1.645 .

Note this says that there is a 98% chance that a standard normal random variable lies within 2.33

standard deviations from 0 (the mean) which is to say that Z lies between

−z .01=−2.33 and z .01=2.33 since .02 is the probability of the complementary event that Z is either

greater than 2.33 or that Z is less than -2.33 by symmetry since both of these disjoint events have the

same probability .01.

Note that to say that roughly 95% of the area under the standard normal lies within two standard

deviations of the mean is to say that z .025 is close to 2 or equivalently that the cumulative distribution

function F(-2) is close to .025 ( table 3 of Appendix B gives this as F(-1.96 )) From this table it would

thus be more accurate to say that 95.44% lies within two standard deviations and that 95% lies within

1.96 standard deviations of 0 (the mean) .

Normal Approximation to the Binomial distribution

We have already encountered the Poisson approximation to the binomial distribution which was

derived in the regime for which the number of trials or sample size n is large (exactly Poisson in limit

n∞ )

while success probability p is small so that the mean number of successes in n trials np= is fixed.

The normal approximation works in the different regime where both np15 and n1− p15 .

For n sufficiently large it is possible that both regimes overlap so that both approximations are valid

and yield approximately the same answer. .

Recall that for a binomial random variable with parameters n and p

X = the number of successes in n Bernoulli trials

we can regard X as a sum of n independent identically distributed (i.i.d.) Bernoulli ( 0 or 1 valued)

random variables each having expected value the success probability p. Since the mean and standard

deviation of this binomial random variable we know are E [ X ]=np and X = n p1− p one then

has

Theorem 5.1 of the text (normal approximation to the binomial distribution) :

X −np

The standardized variable Z=

is approximately standard normal and becomes exactly

np 1− p

so in the limit as n ∞ . This will generally be a good approximation provided both

np15 and n1− p15 so that implicitly n30 (Jay Devore's Statistics for Engineers book

≥10 instead of > 15 ) This is a special case of the

uses

n

Central Limit Theorem (Theorem 6.2 of the text). Any sum

S n=∑ X i of a large number of i.i.d.

i =1

(independent identically distributed) random variables X i each having mean =E [ X i ] and finite

variance V [ X i ]= 2 ( n > 30 in practice is usually large enough ) is approximately normally

distributed. As we have seen the standardized variable will then be (approximately) standard normal.

Specifically

WEEK 6

page 8

S n−n

x −

=

/n

n

is approximately standard normal for large n.

Z=

To get the second expression on the right we have divided numerator and denominator of the quotient

S

on the left by n . Here x = n is the sample mean. Since x is a sum it is approximately normal for

n

large n. Since constants factor outside expectations and the expected value of a sum is the sum of the

n

1

1

expected values we have E [ x ]= ∑ E [ X i ]= n = which says that

n i=1

n

the expected value of the sample mean is the population mean :

E [ x ]=

(said differently the sample mean is an unbiased estimator for the population mean).

Similarly since the variance of a sum of independent random variables is the sum of the variances but

constants get squared before being pulled outside the variance we have

2

2

2

1

1

V [ x ]=

V [S n ]=

n 2=

n

n

n

so that the standard deviation of the sample mean x is

x= / n

The continuity correction is typically used when approximating a discrete count random variable like

the binomial random variable X by a continuous random variable as in the standard normally

distributed Z in the above normal approximation to the binomial. That is we view the discrete event

say

{ X =14 }

as equivalent to the continuous event

{13.5 X 14.5 } .

for purposes of approximating the standardized variable by a standard normal one by Theorem 5.1.

Similarly for the events

{ X ≤14 }={ X ≤14.5 }

and for

{ X ≥14 }={ X ≥13.5 }

We would have for example the approximation that a standard normal random variable Z satisfies

13.5−np

X −np

14.5−np

P X =14=P

Z=

np 1− p

np 1− p np 1− p

To see that some kind of continuity correction is needed , note since continuous random variables take

specific values with probability 0, there is 0 probability that a standard normal takes the specific value

14−np

corresponding to the single value X =14 . However, the density function of the

np 1− p

standard normal evaluated at this value in the middle of the above interval does make sense and when

this function value is multiplied by the length of the small interval 1/ np1− p (proportional to

1/ n ) we get an approximation to the integral of the nearly constant density. The central limit

theorem applied to discrete integer valued random variables possibly re-scaled (or “lattice valued”) is

usually stated in this way by evaluating the density at a specific location and multiplying by the length

of the interval. Higher order corrections involving a polynomial times the standard

normal density are at times used.

WEEK 6 page 9

EXAMPLE 3 Thus when flip a fair coin 36 times so n = 36 and p = 1/2 we'd have the chances of

seeing 14 heads is approximately (with np=36 /2=18 and np 1− p =3 ) using table 3 of

Appendix B for the standard normal cumulative distribution function F (x) which is the area to the left

of x under the standard normal curve :

13.5−18

X −18 14.5−18

P X =14=P

Z=

3

3

3

= P −3/ 2Z −7/6=F −7/ 6−F −3 / 2=F −1.166−F −1.5

= .1216−.0668=.0548

where we have used linear interpolation to arrive at F( -1.166) which is 2/3 of the way between the two

values F( -1.16) =.1230 and F(-1.167) =.1210 whose difference .0020 is roughly .0021 so 2/3 of this

is .0014 less than .1230 equals .1216. Note again that the probability

P aZ b=F b −F a

equals the difference of the cumulative distribution function F for these values since the probability

that the standard normal variable Z lies between a and b is just the area under the standard normal

curve between a and b which is the area F(b) to the left of b minus F(a) ( the area to the left of a )

EXAMPLE 4 Problem 5.37 of the text : The probability that an electronic component will fail in less

than 1000 hours of continuous use is 0.25. Use the normal approximation to find the probability that

among 200 such components, fewer than 45 will fail in less than 1000 hours of continuous use.

We have the probability of failure in less than 1000 hours of continuous use is the binomial parameter

p = 0.25

while the the sample size parameter is

n = 200.

Our binomial random variable is then

X = The number of the 200 components which fail in less than 1000 hours of continuous use

which has mean E [ X ]=np=50 and standard deviation X = np1− p= 50⋅3/4=5/ 2 6 We

want to find (using the continuity correction )

X −50 44.5−50 −11/2

P X 45=P X 44.5= P Z =

=

=−.8981

5 /2 6 5/ 2 6 5/2 6

(Be careful here to use 44.5 and not 45.5 ! ) From table 3 of Appendix B ,

P Z −.8981≈P Z −.90=.1841

The mean and variance of a uniform [a,b] random variable X :

To see that the mean of a uniform [a,b] is

ab

=

2

and the variance of a uniform [a,b] is

1

2

2

= b−a ,

12

recall such a uniform random variable has constant density on the interval of x values from a to b

of width b-a so since the total probability = 1 is just the area under this rectangle , the constant density

which is the height f x of the rectangle must equal 1/(b-a) . Since the density is 0 outside of the

interval [a,b] , we have for the mean

b

b

2

2

1

1 b a

ab

=E [ X ]=∫ x f x dx=

x dx=

− =

and to compute WEEK 6 page 10

∫

b−a a

b−a 2 2

2

a

the variance we have

b

b

1

1 b3 a3 a 2abb2

2

2

E [ X ]=∫ x f x dx =

x 2 dx =

− =

. Subtracting off

∫

b−a a

b−a 3 3

3

a

2

2 ab

=

and simplifying gives the result (since 2 =E [ X 2 ]−2 ) .

4

EXAMPLE 5 problem 5.47 of text : From experience Mr. Harris has found that the low bid on a

construction job can be regarded as a random variable X having the uniform density

3

2C

f x =

for

x2C

4C

3

and f x =0 elsewhere, where C is his own estimate of the cost of the job (what it will cost him).

What percentage z should Mr. Harris add to his cost estimate to maximize his expected profit?

If Mr. Harris bids (1+z) C , if the low bid X is less than his bid he will make no profit (and have no

costs) but he will be paid (1+z) C if the low bid is greater than his bid of (1+z) C so that he wins the

job but it will cost him C so his net profit is then z C. Thus his expected profit is just his profit zC times

the probability of obtaining that profit (which is the probability that the low bid exceeds his own) or

3

3

zC⋅P 1 z C X 2C= zC

2C−1z C = z 1−z C .

4C

4

This will be maximized when z(1-z) is maximized so when he charges a z =1/2 = 50% mark up over

his actual cost estimate.

The log-normal distribution arises when we have a random variable X whose logarithm log X has a

log X −

normal distribution with mean and variance 2 so that the standardized variable Z =

is standard normal. Note that for such a random variable X > 0 since otherwise the log would not exist.

The density of a log-normal random variable X is

1

=

x−1 e−log x− / 2 for x0 , 0

2

2

2

and is 0 elsewhere.

To see this note that the cumulative distribution function of X is related to the cdf of a standard normal

random variable Z by

log X − log x−

log x−

F X x=P X ≤ x=P Z =

≤

=F Z

=F Z z

log x−

where z=

. Recall that by the fundamental theorem of calculus the density is the derivative

of the cumulative distribution function so

log x−

d

d

d

dz

f X x= F X x = F Z

= F Z z ⋅

dx

dx

dz

dx

dz

1 − z /2 1

= f Zz =

e ⋅

dx 2

x

2

since by the chain rule we first compute the derivative of

F Z z with respect to z which gives the

log x −

multiplied by the

WEEK 6 page 11

derivative of z with respect to x. Plugging in the expression for z in terms of x gives the result.

standard normal density in the variable

z=

The Gamma distribution and its special cases the exponential and chi-squared distributions :

This distribution has density

1

−1 −x/

f x=

x e

for x0,0 ,0

and is 0 elsewhere. Here is the gamma function defined by

∞

=∫ x −1 e−x dx

0

which satisfies =−1 −1 and hence =−1! when is a positive integer

which can be seen by integration by parts.

The mean of the gamma distribution is

=

and the variance of the gamma distribution is

2 = 2 .

The exponential distribution corresponds to the special case where =1 which gives for the

density of an exponential random variable :

1

f x= e−x/ for x0, 0

and f(x) = 0 elsewhere.

The mean and variance of an exponential random variable are then

= and 2= 2 .

Alternate form of the density of an exponential random variable in terms of the parameter

=1/

− x

f x= e

for x0,0

so that the mean and variance are then =1/ and 2=1/2 .

The cumulative distribution function for an exponentially distributed random variable :

x

F X x =P X ≤ x=∫ e− t dt = 1−e− x

= 1−e−x/

0

Note this says that

P X x = 1− F X x = e − x

To good approximation the lifetime T of a tungsten filament light bulb is exponentially distributed.

There we would replace x above by a time t in which case P T t = e− t gives the probability that

the lifetime of the bulb exceeds the time t.

The exponential distribution is the only one which has the

Memoryless Property : an exponentially distributed lifetime random variable T is the only distribution

which has the property that for positive times t and s

P T ts | T s= P T s ( memoryless property )

This says for example that if the light bulb has lived for 100 years, the distribution of the remaining

lifetime left is the same as if the bulb were brand new !

We won't show the “only” part but the memoryless property itself is a simple

consequence of the definition of conditional probability since

WEEK 6

page 12

PT ts e − ts −t

P T t s |T s=

= − s =e =P T t

PT s

e

Note above that the intersection event {T ts and T s } is the same as the event {T ts }

since the latter implies {T s } as well.

Relationship between Poisson process and exponential random variables : Recall a Poisson process

X(t) = number of events occurring in a time interval of length t

with mean arrival rate ( = the expected number of events occurring per unit time) is one with

t k − t

P X t=k =

e

k!

Then the waiting time until the first arrival (first event) or the time between successive arrivals

(events) has an exponential distribution with parameter =1/ = . Again waiting times until the

first event or

Waiting times between events in a Poisson process are exponentially distributed.

To see this note that for the waiting time T =T 1 until the first event , saying that T exceeds time t is

the same as saying that 0 events have occurred in the Poisson process :

P T t=P X t =0=e− t

but this is exactly the tail probability of an exponential random variable with parameter =1/ =

( The complementary event is exactly the cumulative distribution function of an exponential. )

Similarly for the waiting time T =T 2 between the first and second events we have

P T 2t | T 1=s=P 0 events in (s, s+t] | T 1=s

= P 0 events in (s, s+t] =e − t

The last two equations follow by the independence and the stationarity (i.e identical distribution) of

disjoint equal time increments assumptions of the Poisson process. But then by the law of total

probability

P T 2t=∑ P T 1=s P T 2t | T 1=s =e− t ∑ P T 1=s =e−t

s

s

(The first sum is a kind of conditional expectation = E [ P T 2t | T 1 ] ) Similarly one sees that all

the inter-arrival times (waiting times between two successive events) are independent and identically

distributed exponential random variables.

The Poisson assumptions are often satisfied hence Poisson processes arise naturally in the real world

and so exponential random variables often occur as waiting times between Poisson events. Recall

the

Assumptions used to obtain Poisson distribution as a limit of Binomial probabilities were :

1) Probability of 1 event occurring in a small time interval proportional to the length t=t /n

of the time interval, with constant but does not depend on when the interval starts so :

2) identically distributed on each time sub-interval (1 event happens with probability p= t )

(A process not depending on time is called a stationary or time homogeneous process) ,

3) events in disjoint time intervals are independent,

4) Probability of more than one event occurring in a small time interval is negligible : This is what

insures only two possible outcomes (either 0 events happen or 1 happens) WEEK 6 page 13

in a small enough time interval hence Bernoulli 0 or 1 valued trials in the small sub-intervals of

time but the sum of a large number of Bernoulli r.v.'s gives a Binomial number of events in the

large time interval.

Interpretation of the parameter of an exponential random variable : We can view the parameter

of an exponential random variable as the rate per unit time at which events happen (in the light

bulb case the event that the light bulb dies) whereas =1 / gives the mean time until the event.

This is similar to the situation for geometric random variables where the probability 1/6 that a roll of a

six sided fair die produces a 3 (success) we can regard as the rate at which successes (3's) happen per

roll of the die while the expected time 6 until a 3 is rolled corresponds to the mean time until the event.

EXAMPLE 6 : A skillful typist has a low probability of making a typo on a typed page of text. There

are a large number n of characters on a page n =2500 say. Assuming typo errors occur independently

for each character with the same small probability p, the binomial (2500 t, p) number of typos on t

pages is then well approximated by a Poisson process with parameter t giving the mean number of

errors for t pages and =np=2500 p the mean number of errors in a single page.

The waiting time T (measured in number of pages typed which may be a fraction of a page) until the

first error occurs or between two successive errors is then approximately exponential with parameter

. Note that if =3 gives the mean of the Poisson number of errors on a page then we expect to

wait for “time” 1/3=1/ of a page until the first error occurs which agrees with the formula for the

mean of an exponential, in this case the exponential waiting time until the first Poisson event (a typo)

occurs. We are viewing time as continuous when in fact the smallest fraction of a page here is 1

character or 1/2500 of (the number of characters making up) a page. In reality the time we have to wait

in units of number of characters typed or 1/2500 of a page is a geometric random variable with small

parameter p and is only approximately exponential.

P X =k =P T =t=P t−1/ 2 tT T 1 /2 t (<--continuity correction)

= the probability we ' ll wait for k characters to be typed until the first error

with X a geometric random variable, T = X /n is the waiting time with t=k /n measured in pages

P X =k =1− pk−1 p where p=/n=/2500 .

By the same approximations used to approximate a binomial by a Poisson random variable, n large, p

small, np= fixed, for “time “ t pages typed the number of characters typed is k =n t=2500 t

so that with t=1/n=1 /2500 of a page giving the “time” to type one character

t = k /2500 = k /n and P X =k =1− /nnt −1 /n =P T =t≈ e− t t

Relationship between exponential and geometric r.v.'s : The geometric random variable is the

discrete analogue of the exponential and becomes exponential in the limit in which we take

k =[nt ] is the greatest integer less than or equal to nt so that time is then approximately t≈

k

n

1

gives the time interval between successive values of k and probability per unit time

n

scales as in the Poisson process as p=

(same assumptions and same approximations used ) so that

n

[nt ]−1

k−1

P X =k =1− p p = 1−

≈ e−t / n = e− t t

n

n

= P k −1/2/n X /nk 1/ 2/ n = P t− t/ 2T =X / ntt /2

and

t=

using the continuity correction. In the limit as n ∞ with np= fixed,

WEEK 6 page 14

we see the geometric random variable X re-scaled by 1/n is then approximated by an exponential r.v. T

with parameter

EXAMPLE 7 Suppose calls arrive at a telephone switchboard according to a Poisson process with rate

one call every four minutes on average (so mean number of calls per minute is .25) Then

X = the number of minutes between successive calls

is an exponential random variable with mean rate =.25 (or equivalently =4 ) so

a) the probability that more than 4 minutes elapse between successive calls is

−.25 4

−1

P X 4=e

=e =.368

We could also have obtained this via the complementary event :

−.25 4

−1

P X 4 = 1−P X ≤4=1− F X x =1−1−e

=e

b) The mean time between successive calls is

1

= 4 minutes .

For exponential random variables the mean is also the standard deviation so

the standard deviation of X the time between successive calls is also

X = 1 =4 minutes

c) Find the probability that a call arrives in less than 3 minutes :

−.25 3

P X 3=F 3=1−e

=.5276

E[ X ] =

d) Find the probability that no calls arrive in a 8 minute interval :

P X 8=e− .258=e−2=.1353

Note that this is also the probability of deviating by at least 1 standard deviation from the mean.

e) Find the probability that the next call arrives sometime between the 2nd and 3rd minute after the last

call

P 2 X 3=F 3− F 2=1−e−.25 3−1−e −.252 =e −.25 2 −e− .25 3=.60653−.47236=.1342

EXAMPLE 8 Consider 4 identical components connected in series, each of which has an exponential

lifetime X i with parameter =.01 independent of the lifetime of the other components.

----1----2----3----4---- The system fails as soon as any of the components fails. Let

X = lifetime of the system = min X i ; i=1,2,3,4

= minimum of the lifetimes of each component

a) express the event { X t } that the system is functioning at time t in terms of the events

{ X it } ; i=1,2,3,4

{ X t }={ X 1t }∩{ X 2t }∩{ X 3t }∩{ X 4t }

b) What is the probability that the system functions at time t ?

By independence and the identical nature of the components this is just

P X t=P X 1t P X 2t P X 3t P X 4t =P X 1t 4=e− t 4=e−4 t=e−.04 t

which is exactly the tail probability of an exponential random variable with parameter 4 . Thus the

system life is exponential with parameter 4 .

(Note : There is nothing special about the number of components being 4 here. Moreover the above

discussion illustrates how to find the

WEEK 6 page 15

distribution of the minimum of a collection of independent random variables from the distribution

of each of them )

It can be shown that the sum of independent gamma random variables each with the same

parameter but arbitrary values i of the parameter will also have a gamma distribution with the

same and with parameter =∑ i = the sum of the i 's. Thus the

i

sum of n independent exponential random variables with the same parameter =1/ (which are

gamma with =1 ) is not exponential but rather a special case of the gamma distribution known as

the Erlang distribution (gamma with parameters =n and =1 / ).

The chi-squared distribution with parameter corresponds to the special case of the gamma

distribution with = /2 and =2 and is the distribution of the X 2 random variable

n

n−1 S 2

1

2

X 2=

S

=

X i −x 2 is the sample variance of a sample of size n drawn

when

∑

2

n−1

i =1

from a normal population having variance 2 . Here the parameter =n−1 is called the number

of degrees of freedom. The chi-squared distribution is thus essentially the distribution of the sum of

squares of normally distributed random variables and can easily be used to give the distribution of the

sample variance of a sample drawn from a normally distributed population. We only mention here its

relation to the gamma distribution but will postpone further discussion until chapter 6.