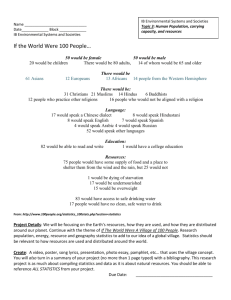

The South Village

advertisement