What We Need to Know About Scientific Names

advertisement

What We Need to Know about Scientific

An Example with White Clover

Gary W. Fick* and Melissa

ABSTRACT

Thereis a shortageof currentinformation

on the nomenclature of cropsprepared

for the classroom.

Thisarticle is written

for studentsandinstructorsin the plantscienceswiththe goal

of illustrating the applicationandusefulnessof plant nomenclature andrelated taxonomic

concepts.Whiteclover (Trifoliumrepens L.) makesa goodexample.It is familiar to many

students,is easily grownfor classroom

demonstrations,

andhas

an interesting nomenclature

to matchits great diversity. Its

nomenclature

is usedto explaininfraspecificnamesandauthority designations.Thehistoryof scientific names

for whiteclover

illustrates howand whynameschangeand howprecision in

scientific communication

canbe increasedby the use of scientific names.Themainexamplefor increasedprecisionis the

comparison

of the size groupsof whiteclovercultivars withthe

scientific namesfor the infraspecificranksof the samegroups.

Typespecimensandthe associatedtaxonomicdescriptionsare

requiredfor scientific namesandmakepermanent

andobjective referencepoints. Thescientific namesrecommended

for

the three common

size groupsof white clover are the following: (i) TrifoliumrepensL. f. repens,the smallor wildgroup;

(ii) T. repensf. hollandicum

Erithex Jfiv. &So6,the intermediate or Dutchgroup;and(iii) T. repensvar. giganteumLagr.Foss., the large or Ladinogroup.

TrlE

trsE of scientific (Latin) names necessary for

precise communication of biological information

across time (history) and space (languages and regions).

As students, we are usually required to memorizescientific names, but it is more important that we knowhow

to interpret and use the scientific names we encounter.

Unfortunately, taxonomic instruction seems to be frequently slighted in the applied plant sciences. This article

and its accompanying appendices are intended to help

teachers and students with limited taxonomic training

better understand, interpret, and use the scientific names

of plants.

White clover (Trifolium repens L.) was chosen as the

example species because most plant science students

(Homosapiens L.) will be familiar with this widely distributed and common

plant. It can be easily grownin pots

for interesting classroom demonstrations that illustrate

various taxonomic concepts. The nomenclature of white

clover also provides ready examplesof three points that

often puzzle plant science students: (i) why "binomial"

names are sometimes so long and complicated, (ii) how

G.W.Fick, Dep.of Soil, Crop,andAtmospheric

Sciences,andMelissa

A. Luckow,

BaileyHortorium,

CornellUniv., Ithaca, NY14853.Contribution fromthe Dep.of Soil, Crop,andAtmospheric

Sciences,Cornell Univ.Received2 Feb. 1990.*Corresponding

author.

Publishedin J. Agron.Educ.20:141-147

(1991).

Names:

A. Luckow

scientific names add precision to communicationsabout

crops, and (iii) whyscientific namesfor a particular kind

of plant can change. Our primary goal is to illustrate and

clarify the issues related to these three questions. In addition, we hope this article will encourageapplied scientists to consult taxonomists when they have questions

about plant nomenclature.

WHY NAMES CAN BE SO LONG

Most persons with biological training will remember

the rudiments of biological nomenclature. A species name

consists of two words: a genus name, which is capitalized, and a specific epithet, whichis not capitalized. Both

are in Latin and are either underlined or italicized. In

addition, the species name is followed by an authority

designation that refers to the author of the name. In the

species namefor white clover, Trifolium repens L., Trifolium is the genus name,repens is the specific epithet, and

Linnaeus(abbreviatedL.) is the authority. If it is not confusing, the genus name may be abbreviated and the

authority deleted in subsequent uses in the same paper.

For example, the above may be shortened to T. repens

once it is given in full.

Whenwe need to find and use a scientific name, we

can look it up in a handy flora or a standard reference

such as Hortus Third (3). The confusion begins when

find a nameof more than two Latin words or an authority

that is long and complicated. For a complexspecies like

white clover, additional Latin epithets sometimesfollow

the species nameto indicate infraspecific subdivisions of

the species. Such nameswill have designated ranks, usually subspecies (ssp.), variety (var.), or form (f.),

latter (lower) rank encompassedby the former. A group

of similar plants at any rank is called a taxon (plural,

taxa). The name for a taxon below the rank of genus

should also have an authority that follows the name, e.g.,

T. repens ssp. nevadense (Boiss.) D.E. Coombe.The long

authority for the subspecies nevadenseindicates that this

kind of white clover was first described by Boissier (abbreviated Boiss.) in a different genus, as a separate

species, or at a different rank. It was later madea subspecies by D.E. Coombe.

The current rules of plant nomenclature (14, 18) allow

the taxonomist to define the factors that separate ranks,

and this can cause confusion (4). Subspecies are usually

defined as geographically distinct parts of a species, but

both subspecies and varieties are variously defined as geographic, morphological, or economic(i.e., wild vs. weed

vs. crop) groups within a species (4). To avoid confusion,

most taxonomists refer to subspecies or varieties but not

both. Forms usually represent morphologically distinct

J. Agron.Educ., Vol. 20, no. 2, 1991 141

Table 1. Comparisonof citation systems found in the "long style"

of authority designation used with scientific namesand reference listings used in society journals. Three taxa of white clover

serve as examples.

Example

Authority

or reference

Scientific namesand authority designations

1. Trifolium repens L., Sp. PL 767. 1753.

2. T. repens L. f. hollandicumErith ex Jhv. & So~, A MagyarnOvdnyvilhg

kdzikonyve 330. 1951.

3. T. repens L. var. giganteumLagr.-Foss., F1. Tarn Garonne95. 1847.

References

1. Linnaeus, C. 1753. T. repens p. 767. In Species plantarum.

2. J~vorka, S., and R. Sod. 1951. T. repens L. p. 330-331. In A Magyar

n0vdnyvil~g

k~zikOnyve.

Akaddmiai

Kiadd.

3. Lagreze-Fossat,

A. 1847.T. repens,

p. 94-95.In Florede Tam et

Garonne.

Rethord,

Montauban.

but minor kinds of variability.

Subsequent examples

illustrate infraspecific classification, but it should already

be clear that more than a binomial name might be needed

with some complex species.

Authority designations can also get complicated. The

authority citation is really a reference to scientific literature. The science of plant taxonomyhas developed its

ownconventions of style for citing original references,

and there are three methods in use:

1. The short style in which the citation is reduced to

the author’s name, often abbreviated, e.g., Trifoo

lium repens L.

2. The name-and-year style in which the publication

year is added, e.g., T. repens L. 1753

3. The long style in which the full reference is cited,

e.g., T. repens L., Sp. PI. 767. 1753

The short style is commonlyused in scientific journals.

The name-and-year style is useful when names are being

comparedfor priority. The long style is used in taxonomic

references where all possible ambiguities must be eliminated (Table 1). The abbreviations for authors and publications are standardized in reference works consulted

by taxonomists(23, 24) so that even the short style should

be traceable to its original source. For this to be possible, care must be given to exactly reproduce authority

designations. Good scientific

writing requires that

authority designations be included for species and infraspecific namesthe first time they are used. It is simply a matter of citing one’s sources. (AppendixI gives

more details about the rules of plant nomenclature.)

BEING PRECISE

Because crop scientists work mainly with species, varieties, and cultivars of plants, most of their taxonomic

questions concern the names of species and infraspecific

groups. White clover is a particularly rich examplewith

at least 232 namedcultivars (6) and about 200 variations

of scientific names for wild populations (9, 25). Many

of the 200 + scientific namesare redundant or illegitimate under the rules of nomenclature, but recent reviews

(15, 25, 27, 28) showthat there are about eight varieties

(or subspecies) in the wild populations (Appendix II).

The International Code of Nomenclature for Culti142

J. Agron. Educ.,

Vol. 20, no. 2, 1991

vated Plants (5) specifies that all infraspecific taxa maintained only by cultivation should be namedas cultivars

(cultivated varieties). Thus, scientific names for subspecies, varieties, and forms should only be used to refer

to wild plant populations. Such populations often

represent the progenitors of moderncrops, the source of

genes in breeding programs, and specialized populations

of weeds and forages that have differentiated spontaneously in agricultural situations. As a complexof cultivated and wild kinds, white clover challenges our

capabilities for precise scientific identification belowthe

species level.

The cultivated code (5) also allows "groups" of similar cultivars to be recognized. Agronomists frequently

divide white clover cultivars on the basis of plant size into

small, intermediate, and large groups (8, 11). The size

differences are important because they affect adaptation,

productivity,

and management options. For example,

small kinds are less productive than large kinds, but small

kinds tolerate close continuous grazing. Large kinds

should be given recovery periods following close grazing.

Caradus (6) briefly described 232 cultivars of white

clover namedin the literature, and relative size was one

of the main points of most descriptions. Because of variable environments and previous interbreeding, there is

complete overlapping of size amongso manykinds. For

comparison, Caradus (6) used old and widely knowncultivars as reference points. Amongthe oldest cultivated

kinds of white clover used for size reference are the following:

1. ’Kent Wild White’: a small cultivar certified in

England in 1930 (6)

2. ’Dutch’: a widely exported agricultural ecotype of

intermediate size that originated in the Netherlands

(6). Records of importation of Dutch white clover

seed to England predate 1750 (8)

3. ’Ladino Gigante Lodigiano’: a large agricultural

ecotype knownin Italy from at least 1760 (6). It was

widely exported, and in the U.S., the term "Ladino" denotes both the old cultivar name and the

group of large cultivars in general (11)

The abovelist illustrates the rules for namingcultivars:

cultivar names are to be capitalized, not in Latin (with

exceptions), of no more than three words, and enclosed

by single quotation marksthe first time they are used (5).

Unfortunately, many cultivars that are properly named

have not been carefully described or formally registered.

Consequently, comparisons like those of Caradus (6) can

be very useful to a plant breeder or farm advisor who

is already familiar with white clover. However,relative

comparisons are not clear to someoneunfamiliar with the

reference cultivar, and a reference cultivar maydisappear

when it becomesobsolete. Cultivar nomenclature can be

ambiguousbecause it lacks permanent reference points.

Unlike a cultivar name, a scientific nameis based on

a preserved specimen(the type specimen) and a published

description that distinguishes that taxon from all other

kinds (14, 18). Consequently, scientific names provide

about as precise and permanent a reference point as is

possible. Erith (8) was the first to use scientific names

Table 2. Measurementsof the size for the three cultivated

of white clover.

Plant

characteristic

groups

Small group

(Wild)

Intermediate

group (Dutch)

Large group

(Lad/no)

mostly 25-65

mostly 50-180

6-16

mostly <25

< 120

mostly 50-75

mostly 75-250

9-22

mostly 25-35

> small group

about 2.0

up to 600

mostly >300

up to 55

mostly >35

mostly >300

>3.3

mostly 15-20

mostly 15-25

up to 35§

mm

Petiole length~

Petiole length~

Leaflet length~"

Leaflet length¶

Pedunclelength’f

Stolon diam.¶

Inflorescence

diam.t

FromErith (8).

FromHartwig(16). Plant characteristics are repeated for different sources.

FromSzab6 (25).

Zohary and Heller (28) reported most are 30-35 mm.

to define, in effect, wild progenitors of the three following cultivar groups:

1. var. sylvestre Alef. ("wild white clover," of small

size)

2. var. sylvestre Alef. race hollandicumErith ("white

Dutch clover," of intermediate size)

3. var. sylvestre Alef. race giganteum (Lagr.-Foss.)

Erith ("Lodi or Italian white clover," of large size)

These three groups are clearly associated with the old

reference cultivars. However,they provide additional information because they have type specimens for reference and published descriptions to distinguish them. In

addition, Erith (8), Szab6 (25), and other workers measured the variability in each of the three groups and

recorded actual size ranges (Table 2). Althoughthe size

parameters have some inconsistencies and may not be

completely accurate for all environments where white

clover is nowgrown, they certainly add quantitative detail to relative statements about size. Becausereference

standards exist for scientific namesbut not for those of

cultivars, the descriptions of cultivars as well as wild plant

populations becomemore precise if they can be related

to infraspecific taxonomic categories.

WHY NAMES CHANGE

One of the main functions of botanical nomenclature

is to provide a basis for determining the accepted scientific namefor each kind of plant. A basic rule is that the

accepted name will be the oldest name, beginning with

Species Plantarumwritten by Linnaeus in 1753 (14, 18).

A scientific name can be changed if an older name with

a type specimen and properly published description is

found for the same kind of plant. Since T. repens is found

in the starting reference, it cannot be replaced because

of priority. However, it has replaced other names. The

Russian botanist C. von Steven (26) named a kind

white clover T. nothum Steven in 1856, apparently believing that it differed from the species already named

by Linnaeus. T. nothum is now regarded as a legitimate

but incorrect name and is said to be a synonymof the

accepted name, which is T. repens.

Another reason that a namecan change is the development of new taxonomic concepts. Botanist K.B. Presl (21)

believed that the genus Trifolium should be divided, one

part becoming a new genus Amoria. White clover thus

becameA. repens (L.) K. Presl. This name is nowregarded as a synonym of T. repens by most taxonomists because they do not believe the Amoria taxon warrants

species status. If they did, A. repens wouldbe the correct name. The authority designation of A. repens is

another example of the citation of two authors for one

name. The authority in parentheses (the "parenthetical

authority") is retained because the delineation of the taxon and the type of specimenare associated with that reference. The authority outside the parentheses (the

"combining authority") is added because the taxonomic position (the genus or rank) has been changedby placement of the taxon into a "new combination" by that

authority and reference.

The evolution of taxonomicconcepts leading to several

scientific namechanges is illustrated by the development

of scientific names for the cultivated groups of white

clover (AppendixIII). Erith’s system (8) was the first

recognize three progenitors of the cultivated groups, but

as far back as 1847, Lagreze-Fossat (19) proposed three

size taxa for white clover: (i) T. repens L. (the taxon of

Linnaeus); (ii) T. repens var. giganteumLagr.-Foss. (the

large kind); (iii) T. repens var. microphyllumLagr.-Foss.

(a "very small" kind).

In 1866, Alefeld (1) simplified the concept by splitting

the above groups in half and reducing the number of

groups to two: (i) T. repens var. silvestre Alef. (the wild

kinds); and (ii) T. repens var. cultum Alef. (the cultivated

kinds). Ascherson and Graebner (2) and Gams(10)

agreed with that approach and formulated a taxonomy

to represent the degree of relatedness of the taxa in question. All were placed together in T. repens var. typicum

(Aschers. & Graebn.) Gamsin Hegi. Within this group

were three forms: (i) f. giganteum (Lagr.-Foss.) Gamsin

Hegi (large kinds); (ii) genuinum(Aschers. & Gra ebn.)

Gamsin Hegi (small and intermediate kinds); and (iii)

f. microphyllum (Lagr.-Foss.) Gamsin Hegi (very small

kinds). Erith’s 1924 revision (8) mentionedin the previous section replaced var. typicurn with the older name

var. sylvestre Alef. She also split f. genuinumto recognize a distinct group of intermediate size, i.e., race hollandicum Erith. The result was three size-based taxa for

the progenitors of moderncultivars, with both hollandicum Erith and giganteum (Lagr.-Foss.) Erith given the

rank of race. Erith (8) stated that f. microphyllum

represented only environmentally stressed specimens of

the small kind, var. sylvestre. It appears that no one has

proven otherwise.

The names proposed by Erith (8) have also been

changed, though the taxa she recognized still stand. After

Erith’s work, the rules of nomenclature were formalized

and specified that the nameof a taxon should be repeated

at lower ranks with the same type specimen. Thus, names

such as typicum, genuinum, and sylvestre were replaced

by repens in the scientific names for the kinds of white

clover. J~vorka and Sob (17) used the more standard rank

of form (f.) as an alternative to the races of Erith (8),

and Zoharyand Heller (28) reinstated the older treatment

of giganteum as a distinct variety. The three wild proJ. Agron. Educ.,

Vol.

20, no. 2, 1991 143

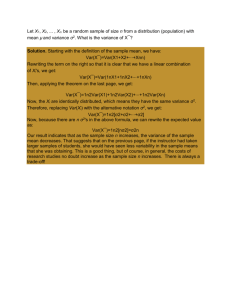

Table3. Aclassificationof the wildprogenitors

of cultivatedwhite

clover that combinesagronomic

andtaxonomicperspectives.

Eachscientific nameis in a column.

Smallgroup Intermediategroup

Largegroup

Rank

lWild~

{Dutch)

{Ladinol

Trifolium

Tdfolium

Genus

Tdfolium

Species repensL.

repens

repens

Variety repens

repens

giganteum

Lagr.-Foss.

hollandicum

Form

repens

giganteum

Erith ex Jhv. &Sod

genitors of cultivated white clover maynowbe designated

as follows:

1. Trifolium repens L. f. repens (the small kind)

2. T. repens f. hollandicum Erith ex Jfiv. & Sob (the

intermediate kind)

3. T. repens var. giganteum Lagr.-Foss. (the large

kind)

The names for the intervening ranks of these taxa are

given in Table 3.

FROM THE PRECISE TO THE RIDICULOUS

After all this academicintricacy, someoneis likely to

ask, "Whynot just say the white clover is a small, intermediate, or large kind, and forget the Latin?" In some

cases, that maybe adequate, but the adjectives are relative and the species is highly variable across genotypes

and environments. Scientific names provide well-defined

reference points that aid communication.The counter argumentfollows that perhaps the desired result could be

accomplished by simply designating a cultivar group

name, i.e., "Wild, Dutch, or Ladino." This would be

appropriate if only cultivated types were involved, but

in a species like white clover, the scientific namesof the

wild progenitors makethe same distinction while adding

the precision of type specimens. Whenprecise scientific

communication is important, scientific names including

infraspecific ranks can be very helpful. Of course, cultivar and cultivar group names should also be used

whenever they apply.

Other infraspecific names for kinds of white clover

have also been proposed, but their use could lead to confusion. Examplesinclude T. repens var. tetraphyllum Lej.

& Cour. (the four-leaf clover), var. fusco-maculatum

Godet (the bloodwort with purple leaf blotches), and

roseum (Peterm.) Gams in Hegi (purple-flowered white

clover). Since the characteristics of distinction are under

rather simple genetic control (27), a four-leaved, purpleblotched, purple-flowered kind could be found. What

should it be named?For such cases, phenotypic or genotypic codes seem more appropriate than scientific names.

The guiding principle for the use of scientific names

should be to increase precision and to avoid confusion.

APPENDIX !

Additional Rules of Nomenclature

The most frequently applied standards of plant nomenclature were explained in the maintext, but there are addi144

J. Agron.Educ., Vol. 20, no. 2, 1991

tional rules that govern how plants are named. Those

rules are published in the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (14) and are revised every 6 yr. The

rules apply to taxa that are organized into ranks as follows: class, order, family, genus, species, subspecies, variety, and form. Classes are the largest units (have the

highest rank), forms the smallest. The rules of nomenclature only designate the order of ranks and do not attempt to define them. The rules at the species level and

below are emphasized here because they are used most

frequently by crop scientists.

1. The accepted name for a species or infraspecific

rank is the oldest legitimate ("legal") namefor the rank

published in or after Linnaeus’ Species Plantarum in

1753. More recent names for the same taxon are called

synonyms. Synonymsresult when an author inadvertently

gives a new nameto a plant that has already been named.

Exceptions to the rule of priority are strictly regulated

by the code. The choice of beginning publication was

purely arbitrary, but it nowserves as the starting point

for all botanical nomenclature.

2. For a nameto be legitimate, it must be both effectively and validly published. Effective publication means

that the name appears in printed matter distributed to

the general public and maintained in science libraries.

Valid publication meansthat the namesatisfies four additional requirements outlined below.

3. To be valid, each name must have a genus and

specific epithet that are in Latin (see main text). The

names should agree in gender, but correction of gender

and modernization of spelling, e.g. silvestre for sylvestre, are allowed after the nameis published. Additional

Latin epithets for infraspecific ranks are allowed if they

meet the other criteria for validity. Infraspecific ranks

in addition to those designated in the code are allowed,

e.g., "race" and "convariety."

4. To be valid, each scientific namemust have a published description that distinguishes that plant from all

others (see main text). For any new name published after 1958, the description must be in Latin.

5. To be valid, each name must have an identifiable

author. If the name has been changed in rank or genus,

the original author is given in parentheses and is called

the parenthetical

authority. The author making the

change follows outside the parentheses and is called the

combiningauthority (see main text). Nobis (n. or nob.),

mihi (m.), and hoc locus (h.c.) are used in place of the

authority to show that the author of the publication is

the author of the name. Abbreviation for authors’ names

follows strict rules. The correct abbreviations for authorities can be found in references (23) and (24).

6. To be valid, each name must have a preserved reference specimen known as the type specimen (see main

text). The type specimenis the permanentreference point

for a name, so if a name is changed in genus or rank,

the type specimen can be located through the parenthetical authority.

7. Several other special rules apply to authors’ names.

For example, in Trifolium repens L. f. hollandicum Erith

ex J/~v. & Sob, the term ex means that Erith first proposed the name but that J~tvorka and Sob provided the

valid description. Another commonlyencountered case

is exemplified by T. repens L. f. cultum (Alef.) Gamsin

Hegi. The taxon named culture by Alefeld was given a

new rank by Gamsin a book otherwise written by Hegi.

8. There are several errors that will cause a validly published nameto be illegitimate (nom. illegit.). One example is a later homonym,

i.e., an author inadvertently chose

a name that exactly duplicated a name used earlier for

a different taxon. The error is indicated as follows: T.

macrorrhizum Boiss. non Waldst. & Kit. Bossier corrected the mistake himself by altering the rank: T. repens

L. var. macrorrhizum Boiss. His name does not occur

as the parenthetical authority because the first nameis

illegitimate.

9. A namemayalso be illegitimate because it is superfluous (nom. superfl.). For example, the Italian taxonomist Biasoletto proposed the name T. prostratum

Biasol. as an alternative for T. biasolettii Steud. &

Hochst. named in his honor. Because he knew the earlier namealready existed for the taxon, the name he proposed was superfluous. Nymanlater altered the rank of

the same taxon in T. repens L. ssp. prostratum Nym.

Biasoletto is not recognized as the parenthetical authority because his namefor the taxon is illegitimate.

10. Imprecise descriptions, careless interpretations, or

disregard for rules of the code can lead to misidentification of a taxon or misapplication of the name, and such

mistakes may be perpetuated in the literature. The abbreviation auct. (for authors) is used to showthat many

authors have repeated the same mistake. The designation

T. repens L. var. latum, auct. Amer. shows that many

Americanauthors have used that namein error. (In this

case the name was invalid.)

11. The following terms are also used in scientific

names:

hort., hortulanorum: "found in gardens," a cultivar.

nom. nud., nomen nudum’. "naked name," published

without description.

p. p., pro porte: "in part," only part of a taxon is included.

pro syn., pro synonymo: published "as a synonym."

s. auct., sine auctorum: published "without author."

This only begins the interesting and intricate details of

botanical nomenclature. Crop scientists maynot need to

knowall the rules, but they should be able to cite a valid

name, including the authority, and recognize the complicated cases where expert advice is needed. To determine the proper name and authority, two references are

available: Index Kewensis(22), listing all plant names,

their authorities, and place of publication; and the Gray

Card Index (13), similar to (22) but containing only

World plant names.

APPENDIX II

Diversity of the Wild Populations of White Clover

One of the more convincing arguments of the need for

infraspecific taxa is the existence of distinct wild populations within a species. Technical descriptions and keys

to the main infraspecific taxa of white clover are avail-

able in Coombe(7), Gillett (12), and Zohary and Heller

(28). Eight or nine main infraspecific groups are generally recognized, but specialists have not agreed on the

rank of each taxon, and this results in variation in the

number of groups. The most authoritative source is the

recent monograph on Trifolium by Zohary and Heller

(28), and the following list is based on their eight varieties, here subdivided to accommodatetwo other widely

recognized kinds. Wherethe rank is debated, the accepted

name at the alternative rank is included in brackets.

Trifolium repens L.

Taxon1: var. biasolettii (Steud. & Hochst.) Aschers.

Graebn. [ssp. prostratum Nym.]

¯ flowers pale pink, heads mostly 14 to 18 mmdiam.

¯ petioles densely hairy, leaflets mostly 5 to 10 mm

long

¯ range: dry habitats and sunny slopes in the Mediterranean zone from France to Turkey

Taxon lb: IT. occidentale D.E. Coombe= T. repens ssp.

occidentale (D.E. Coombe)M. Lainz; treated as

synonym of Taxon 1 by Zohary and Heller (28)]

¯ similar to Taxon 1 but with slightly larger flower

heads (mostly 20-24 mmdiam.) and sparsely hairy

petioles

¯ range: sand dunes along English Channel and Atlantic coast of southern Europe

Taxon 2: var. giganteum Lagr.-Foss. [var. repens f.

giganteum (Lagr.-Foss.) Gamsin Hegi]

¯ flowers white to pale pink, heads > 30 mmdiam.

¯ petioles mostly glabrous, leaflets mostly > 35 mm

long

¯ range: wild populations have been reported from

around the Mediterranean

Taxon3: var. macrorrhizum Boiss. [treated as synonym

of Taxon 1 by Greuter et al. (15)]

¯ similar to Taxon1 but with white flowers and thicker

taproots

¯ range: mountains of Turkey and Iran

Taxon 4: vat. nevadense (Boiss.) C. Vicioso [ssp.

nevadense (Boiss.) D.E. Coombe]

¯ flowers white and heads _< 20 mmdiam.

¯ petioles mostly glabrous, leaflets _< 10 mmlong

¯ range: mountains of Spain and Portugal

Taxon 5: var. ochranthum K. Mal~ ex Aschers. &

Graebn. [ssp. ochranthum (K. Mal~) Ny~r.]

¯ flowers yellowish and heads mostly 25 to 30 mm

diam.

¯ petioles glabrous, leaflets _< 13 mmlong

¯ range: mountains of Romania and Bosnia

Taxon6: var. orbelicum (Velen.) Fritsch [ssp. orbelicum

(Velen.) Pawl.]

¯ flowers cream colored and heads _< 25 mmdiam.

¯ petioles glabrous, leaflets mostly 6 to 8 mmlong

¯ range: Carpathians and mountains of Balkan

peninsula

Taxon 7: vat. orphanideum (Boiss.) Boiss. [ssp. orphanideum (Boiss.) D.E. Coombe]

¯ flowers pale pink and heads of < 12 flowers

¯ petioles glabrous, leaflets mostly 3 to 7 mmlong

¯ range: Sicily to Asia Minor

J. Agron.Educ., Vol. 20, no. 2, 1991 145

Taxon 8: var. repens L.

• flowers white to pale pink, heads mostly 15 to 25

mm diam.

• petioles mostly glabrous, leaflets mostly 10 to 30 mm

long

• range: temperate zones worldwide

Taxon 8b: var. repens f. hollandicum Erith ex Jav. & Soo

• similar to Taxon 8 but with slightly larger leaflets

(up to 35 mm long) and longer petioles (up to 250

mm long)

• range: spontaneous in agriculture of the Netherlands,

now worldwide

The above classification of the infraspecific ranks of

white clover may be altered in the future as more is

learned about ploidy level and hybridization of the various taxa.

APPENDIX III

Synonymy for Cultivated Groups of White Clover

At present, all cultivars of white clover appear to have

been derived from three taxa (2, 8, and 8b of Appendix

II) and their hybrids. The following list illustrates the

name-and-year method of citation used to show priority

and history. Annotations include Latin abbreviations

used by taxonomists to indicate the status of a name.

Within each of the three main taxa, names are grouped

by rank since priority applies within a rank.

Trifolium repens L. 1753. (See Zohary and Heller [28]

and Szabo [25] for a list of synonyms at the species

level.)

ssp. repens L. 1753.

A.I. typicum Aschers. & Graebn. 1908. (Ascherson and

Graebner's rank is ambiguous.)

var. repens L. 1753.

var. silvestre Alef. 1866. (Also spelled sylvestre and sylvestrel.)

var. typicum Fiori & Paol. 1900. p.p. ssp. prostration

Nym. 1878.

var. typicum (Aschers. & Graebn.) Gams in Hegi 1923

non Fiori & Paol. 1900.

A.I.a. 1.0.7. genuinum Aschers. & Graebn. 1908.

(Ascherson and Graebner's "outlined" rank is ambiguous.)

var. repens f. repens L. 1753. ("Wild" white clover.)

var. microphyllum Lagr.-Foss. 1847. (Erith [8] concluded var. microphyllum was simply a depauperate state.)

f. genuinum (Aschers. & Graebn.) Gams in Hegi 1923,

p.p. f. hollandicum Erith ex Jav. & Soo 1951.

f. silvestre (Alef.) Gams in Hegi 1923, pro syn. of

above.

f. microphyllum (Lagr.-Foss.) Gams in Hegi 1923. (See

var. microphyllum above.)

convar. arcto-alpinum Szabo 1988. (A subgroup of

small, cultivated white clovers.)

convar. nanum Szabo 1988. (Another subgroup of

small, cultivated white clovers.)

146

J. Agron. Educ., Vol. 20, no. 2, 1991

var. repens f. hollandicum Erith ex Jav. & Soo 1951

("Dutch" white clover.)

var. cultum Alef. 1866, p.p. var. giganteum Lagr.Foss. 1847.

var. vulgare, s. auct. 1953, in Hartwig (16).

var. hollandicum, s. auct. 1987, in W.M. Williams (27).

f. genuinum (Aschers. & Graebn.) Gams in Hegi 1923,

p.p. f. repens.

f. silvestre (Alef.) Gams in Hegi 1923, pro syn. of

above.

race hollandicum Erith 1924.

convar. hollandicum (Erith) Szabo 1988.

provar. praecox Szabo 1988. (A subset of convar. hollandicum above.)

provar. prolificum Szabo 1988. (Another subset of convar. hollandicum above.)

var. giganteum Lagr.-Foss. 1847. ("Ladino" white

clover.)

ssp. giganteum (Lagr.-Foss.) Ponert 1973.

var. cultum Alef. 1866, p.p. var. repens f. hollandicum Erith ex Jav. & Soo 1951.

var. latum, auct. Amer., s. auct. et nom. nud. 1894,

in McCarthy and Emery (20). (Also spelled latus and

lata.)

f. giganteum (Lagr.-Foss.) Gams in Hegi 1923.

f. lodigense hort. Gams in Hegi 1923, pro syn. of

above.

f. cultum (Alef.) Gams in Hegi 1923, pro syn. of above.

race giganteum (Lagr.-Foss.) Erith 1924.

convar. giganteum (Lagr.-Foss.) Szabo 1988.

provar. bienne Szabo 1988. (A subset of convar.

giganteum above.)

provar. perenne Szabo 1988. (Another subset of convar. giganteum above.)

12. Gillett, J.M. 1985. Taxonomy and morphology, p. 7-69. In N.L.

Taylor (ed.) Clover science and technology. Agron. Monogr. 25.

ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, Madison, WI.

13. Gray Herbarium of Harvard University. 1968-1986. Gray herbarium index. Harvard Univ. Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

14. Greuter, W. (ed.). 1988. International code of botanical nomenclature. Koeltz Scientific Books, Konigstein.

15. Greuter, W., H.M. Burdet, and G. Long. 1989. Trifolium repens.

Med-Checklist 4:189-190.

16. Hartwig, H.B. 1953. Legume culture and picture identification.

M.S. Hartwig, Ithaca, NY.

17. Javorka, S., and R. Soo. 1951. A Magyar nOvenyvilag kezikOnyve.

Akademiai Kiado, Budapest.

18. Jeffrey, C. 1990. Biological nomenclature. 3rd ed. Edward Arnold,

London.

19. Lagreze-Fossat, A. 1847. Flore de Tarn et Garonne. Rethore, Mountauban.

20. McCarthy, G., and F.E. Emery. 1894. Some leguminous crops and

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

their economic value. Bull. North Carolina Agric. Exp. Stn.

98:133-170.

Presl, K.B. 1830. Symbolae Botanicae 1:47.

Royal Botanic Garden at Kew. 1893-1987. Index Kewensis. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Royal Botanic Garden at Kew. 1980. Draft index of abbreviations.

Her Majesties Stationary Office, London.

Stafleu, F.A., and R.S. Cowan. 1976-1989. Taxonomic literature.

2nd ed. Bonn, Scheltema, and Holkema, Utrecht.

Szabo, A.T. 1988. The white clover (Trifolium repens L.) gene pool.

I. Taxonomical review and proposals. Acta Bot. Hung. 34:225-241.

von Steven, C. 1856. Verzeichniss der auf der taurischen Halbinsel wildwachsenden Pflanzen. Bull. Soc. Imp. Nat. Moscou

29(3):121-186.

Williams, W.M. 1987. White clover taxonomy and biosystematics. p. 323-342. In M.J. Baker and W.M. Williams (ed.) White

clover. C.A.B. International, Wallingford, Oxon, UK.

Zohary, M., and D. Heller. 1984. The genus Trifolium. Israel

Academy of Science and Humanities, Jerusalem.