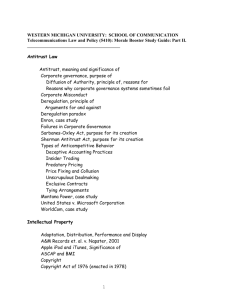

16 Vand. J. Ent. & Tech. 103 - Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment

advertisement